Ocean Newsletter

No.598 October 20, 2025

-

The Future of the Ocean Begins with Knowledge — Linking the Diversity of Life from Deep-Sea Caves to the Next Generation

NARUSHIMA Hikari (Research Assistant, Research Institute for Global Change [RIGC], Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology [JAMSTEC])

The deep-sea cave exploration team “D-ARK” (Deep-sea Archaic Refugia in Karst) is conducting investigations around the Daito Islands, Okinawa Prefecture, to explore deep-sea caves and study the biodiversity in their surrounding environments. We also place great emphasis on outreach activities. During our expeditions, we have organized special online classes that connected our research vessel with elementary and junior high schools on the island, and have hosted exhibition events at aquariums to share our research findings with the public.

-

The Cutting Edge of Research on Coralline Algae: From Biodiversity to Blue Carbon

KATO Aki (Associate Professor, Seto Inland Sea Carbon-neutral Research Center, Hiroshima University)

Coralline algae are a representative example of "calcareous algae," which harden their bodies with calcium carbonate to become rock-like. Research on them has been increasingly active for about 20 years as being organisms highly susceptible to ocean acidification. Recently, it has become understood that algal beds formed mainly by coralline algae are an important coastal ecosystem, maintaining biodiversity and with potential for blue carbon. This article provides an overview of recent research on coralline algae.

-

Aquariums Take on the Challenge of Creating Satoumi in Urban Areas

Yoshida Hiroyuki (Chairman, Suma Satoumi Association)

The satoumi activities begun in 2010 at Suma’s Seaside Aquarium, in collaboration with local fishermen, became the starting point for building trust with local residents and diverse local stakeholders. This led to the formation of the Suma Satoumi Association, whose satoumi activities aim to create a bountiful ocean through the regeneration of clams and the creation of seagrass beds. Furthermore, information on marine life and environments obtained from satoumi is being utilized in environmental education and awareness activities for citizens, thus enhancing the value of the replenished Suma Beach and underscoring the significance of sustaining satoumi over the long term.

-

Challenges Facing Kesennuma, a Fisheries City, and Digitalization Efforts

SAITO Tetsuo (President, Kesennuma Fisheries Cooperative Association)

Regional fisheries cities with sharply declining working-age populations have in recent years been battered by waves of change in the marine environment. In Kesennuma, initiatives are underway to achieve digitalization for improving the efficiency, labor-saving, and productivity of fisheries and aquaculture amid increasing uncertainty.

-

Navigating “America First, but Not Alone” in the Pacific

Jenna J LINDEKE (Visiting Research Fellow, Division of Island Nations, Ocean Policy Research Institute, Sasakawa Peace Foundation)

Since his inauguration this January, the US president has shifted to a transactional foreign policy strategy, where the US must directly benefit. This has included a new tariff regime, the dissolution of USAID, and rescission of most development and climate funding. Among Pacific Island Nations, this has hurt domestic value chains, shrunk national trust funds, triggered mass layoffs in development organizations, and drastically limited the funding available for emergency response. Other donors—including China—are unlikely to fill these gaps in the Pacific. Going forward, it will require creativity and collaboration to meet the outstanding needs of the region.

Navigating “America First, but Not Alone” in the Pacific

US Policy Shifts and the Pacific

The US President seeks to rewrite the global order such that where the US participates, it benefits. This administration favors transactional diplomacy, where every deal has a winner and loser, and America must be the “winner.” Foreign policy is led by trade and backed by security. The president favors swift demonstrations of US military or economic strength, as his domestic power base could shift after the mid-term elections in November 2026. US delegates also—unsuccessfully—sought to remove “climate,” “gender equality,” and “sustainability” from joint statements at the International Conference on Financing for Development this June.※1 This demonstrates a desire to shape global agendas to match US policy.

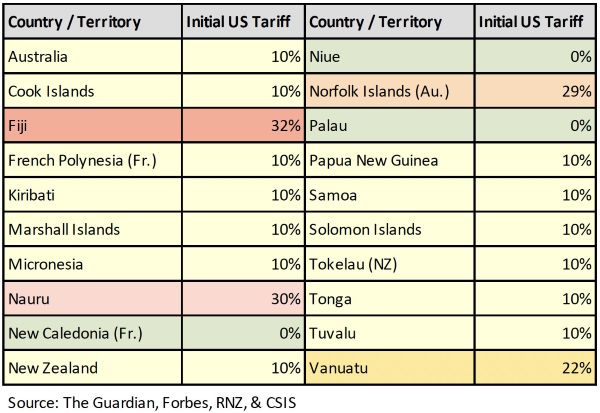

The April 5 “Liberation Day” tariffs placed tariffs of 10%-50% on most countries. Tariffs would devastate local export businesses, sending ripple effects through domestic value chains. For example, Fiji found that the US comprises 100% of exports of some producers. National trust funds dramatically lost value in the wake of global stock market crashes following the tariff announcements. Washington deprioritized tariff negotiations with PICs in favor of larger economies, despite repeated calls from Pacific Leaders. This disregards the previous two presidencies’ plans to reinvest in the Pacific. Only at the end of the 90-day negotiation period did Fiji secure a reduction to 15%, remaining in negotiation over other aspects of trade.

US Cuts to Development Assistance

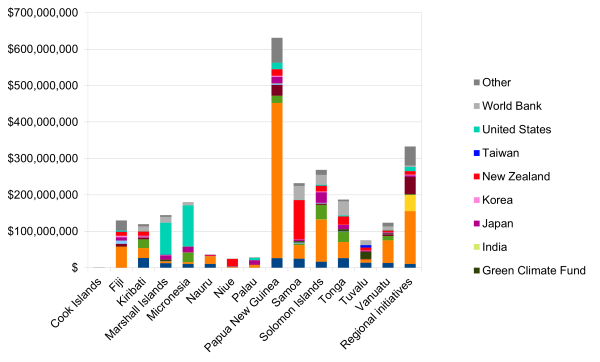

Of similarly devastating impact is the freeze of US development assistance and closure of USAID. American is the world’s largest bilateral donor, providing roughly 10% of total development assistance to the Pacific. Mass lay-offs across implementing organizations have elevated local financial instability. Many of the smallest non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that work directly with communities are struggling to remain operational, while larger organizations’ capacity has drastically contracted.

A leaked list of program cuts revealed termination of over 5,300 grants, retaining only 898.※2 In the Pacific, these cuts overwhelmingly targeted climate change, disaster prevention, emergency response, maternal and child health, governance, and gender empowerment. Meanwhile, remaining projects for PICS tend to benefit American businesses, such as technology or mining cooperation.

The new structure of foreign assistance under the State Department remains unclear, but the President’s 2026 budget request and the State Department’s budget justification gives some clues. Despite absorbing USAID’s responsibilities, the State Department is poised to shrink to 83.7% of its current personnel. Remaining humanitarian assistance, reduced by 48.8%, will be centralized under a federal fund “focusing on crises in which there is a clear, direct nexus to U.S. national interests.”※3 Development assistance from USAID and State is cut and replaced by the $2.9 million America First Opportunity Fund, a 51.5% reduction in international development funding, with a focus on assistance that improves US national security. Global health programs remain, but at 37.9% budget size. Funding for Compact of Free Association (COFA) states (Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau) remains stable, but federal services like weather forecasting will decrease.

The budget also cuts $28.6 million for the East-West Center, America’s leading NGO focused on Pacific Islands, over half its annual revenue. Meanwhile, the forcible closure of the US Institute of Peace, an independent Congressionally-mandated NGO, not only halts its conflict-prevention in Papua New Guinea and PIC information sharing programs, it sets a dangerous precedent that the US government can shutter NGOs working in areas it finds politically objectionable. This budget limits America’s ability to respond to global challenges. Meanwhile, the President is empowered to distribute aid based on his own priorities rather than demonstrated need.

Total Grant Assistance to PICs, 2022

Regional Funding and Security Issues

Responding to US cuts, Australia has slightly increased its overall aid budget, shifting funds towards Pacific gaps. Other donors like the EU, UK, and New Zealand have decreased aid budgets in recent years. While the Asian Development Bank escaped US funding cuts, UN agencies such as the WHO and UNESCO are still grappling with frozen and reduced funds. This will deepen near- and long-term unmet needs in the Pacific.

Conversely, the US Indo-Pacific Command has benefited from the President’s counter-China stance. Funding remains stable, and defense partnerships with PICs continue to expand. The US Coast Guard, which is responsible for both US territories and COFA partners, has also moved additional ships and personnel to Guam. Both are regularly involved in trainings, medical support, and ship-rider operations with PICs. Yet, the proposed budget cuts narcotics control—a previously shared priority with PICs—to 60.8% and converts foreign military financing funds entirely from grants to loans.

Accelerating a trend from the previous administration, the US is rapidly re-militarizaing Micronesia. In addition to expanding military bases on Guam, airstrips across US territories and COFA states are being revitalized to handle modern military aircraft. Proposals for military radars and defense systems are also in progress. While some residents support these projects as important infrastructure, defense, and economic investments, others argue that they pose environmental risks and make targets of the host communities.

The most pressing security concern for many islanders, however, is climate change. However, the US has canceled $4 billion for the Green Climate Fund, rescinded $17.6 million for the UN Loss and Damage Fund, ended contributions to the Global Environmental Facility and the Clean Technology Fund, and withdrawn from the Just Energy Transition Partnership.※4 The Big Beautiful Bill Act also rescinded funds for essentially all domestic environmental protection and clean energy reporting, grants, and programs. As the world’s largest polluter, these US rescissions will have global impacts. While funding for the Pacific Resilience Facility seems to have survived, the above cuts drastically narrow available funding for climate change resilience.

US partners in the Pacific should frame joint initiatives through the lenses of economic or security benefits to the US and visible “wins” for the President. Furthermore, approaching the US with multilateral groupings such as the Pacific Islands Forum or the QUAD may generate more balanced power dynamics. Facilitating South-South triangular cooperation between PICs or with their ASEAN neighbors may also be an effective pathway to maximizing impact with limited development funding. Donors should seek mechanisms for regional and national aid coordination that minimize duplication and gaps, while stretching remaining resources to cover critical needs.

※2 Politico: https://www.politico.com/news/2025/03/26/documents-reveal-scope-of-trumps-foreign-aid-cuts-00252918

※3 President’s Budget: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/appendix_fy2026.pdf, Department of State FY26 Budget: https://www.state.gov/fy-2026-international-affairs-budget/

※4 Carbon Brief:https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-nearly-a-tenth-of-global-climate-finance-threatened-by-trump-aid-cuts/; Devex:https://www.devex.com/news/trump-reneges-on-4b-in-green-climate-fund-financing-109301