Ocean Newsletter

No.587 January 20, 2025

-

Asia-Arctic cooperation and the next phase in Japan´s Arctic engagement

Kristín INGVARSDÓTTIR (Assistant Professor, University of Iceland)

Over a decade has passed since Japan, along with four other Asian countries, was granted permanent observer status in the Arctic Council in 2013. Since then, Japan has actively contributed to Arctic scientific research and strengthened its collaboration with Arctic states. Now, in 2025, Japan is advancing into the next phase of Arctic science and diplomacy. Given the current geopolitical situation, Japan's Arctic cooperation—with both other Asian states and its partners in the Arctic—is probably more important than ever.

-

Polar dialogue: A critical assessment of its inception and potential impact

Santosh Kumar RAUNIYAR (Ocean Policy Research Institute, Sasakawa Peace Foundation)

The 2024 Arctic Circle Assembly introduced the "Polar Dialogue," connecting the Arctic, Antarctic, and the Third Pole (Hindu Kush Himalayan region) to address global climate and geopolitical issues. While this initiative represents a significant step forward it faces key challenges, including bridging governance gaps and ensuring equity, particularly for underrepresented Third Pole regions experiencing rapid glacier melt. Discussions highlighted integrating Indigenous knowledge, fostering community cohesion, and prioritizing nature-based solutions. Geopolitical tensions and distinct regional needs demand inclusive, context-specific governance frameworks. Public awareness of Third Pole issues remains low, necessitating targeted advocacy. The Polar Dialogue’s success depends on actionable strategies, with key milestones like the 2025 Arctic Circle Delhi Forum ahead.

-

Changes in the Arctic Environment Bring Extreme Weather to Japan

HONDA Meiji (Professor of Natural Sciences, Niigata University)

Along with global warming, the Arctic is experiencing rapid environmental changes. The shrinking of snow and ice, such as sea ice, snow cover, and ice sheets, means that the source of the Arctic cold is weakening, and while winters in the mid-latitudes, such as Japan, are generally milder, they are also frequently hit by cold waves and heavy snowfall. This is because the westerly winds are more likely to meander, making it easier for strong cold air to enter temporarily, and even if global warming continues in the future, there is a good chance that we will be hit by unprecedented cold waves and heavy snowfall.

Asia-Arctic cooperation and the next phase in Japan´s Arctic engagement

KEYWORDS

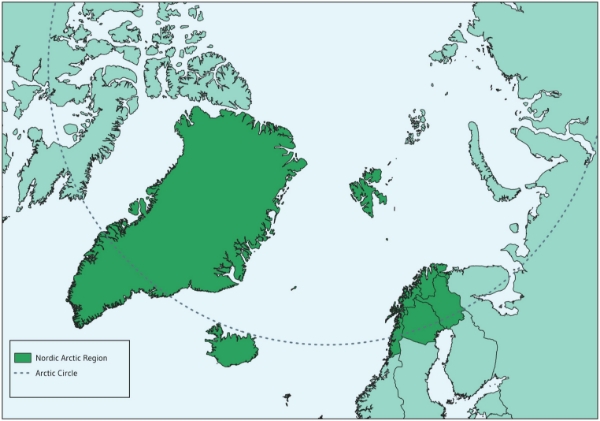

Arctic Council / Asian five / Nordic Arctic

Kristín INGVARSDÓTTIR (Assistant Professor, University of Iceland)

Over a decade has passed since Japan, along with four other Asian countries, was granted permanent observer status in the Arctic Council in 2013. Since then, Japan has actively contributed to Arctic scientific research and strengthened its collaboration with Arctic states. Now, in 2025, Japan is advancing into the next phase of Arctic science and diplomacy. Given the current geopolitical situation, Japan's Arctic cooperation—with both other Asian states and its partners in the Arctic—is probably more important than ever.

Asian Countries' Participation in the Arctic Council

It was a major turning point for Asian-Arctic collaboration when the “Asian five” (China, India, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea) received a permanent observer status in the Arctic Council in 2013. Over a decade has now passed and much has changed in the meantime, not least due to tectonic geopolitical shifts. This article discusses the status of Asian engagement in the Nordic Arctic. There will be a special emphasis on Japan’s role which is about to enter a new phase, starting in 2025.

When the five Asian states applied for permanent observer status in the Arctic Council the attitutes varied greatly among the eight Arctic member states[1]. The Nordic countries[2] were openly supportive of the applications from non-Arctic states; Russia and Canada were “more clearly sceptical,” and the position of the United States was not “actively communicated”[3]. According to Norwegian scholar Leiv Lunde “The Nordic countries […] led by Norway, emphasized the positive aspects of Asia’s interest and saw the region’s greater participation in Arctic affairs as strengthening governance and making the Arctic Council a more relevant and future-oriented forum.”[4]

It is, however, important to keep in mind that the five Asian observer states are by no means similar Arctic or polar actors. For example, Japan stands out for its long polar history: It was the only Asian country among the original signatories of the Antarctic Treaty in 1959 and it was probably the first Asian country to establish a national polar institute. Singapore on the other hand, is the only country among the Arctic five to not yet have an official Arctic policy and does not have a research station in the Arctic, while India is the only country among the Asian observer without an Arctic ambassador. It is clear that the Arctic engagement and “profile” of the Asian five varies greatly.

When the five Asian states applied for permanent observer status in the Arctic Council the attitutes varied greatly among the eight Arctic member states[1]. The Nordic countries[2] were openly supportive of the applications from non-Arctic states; Russia and Canada were “more clearly sceptical,” and the position of the United States was not “actively communicated”[3]. According to Norwegian scholar Leiv Lunde “The Nordic countries […] led by Norway, emphasized the positive aspects of Asia’s interest and saw the region’s greater participation in Arctic affairs as strengthening governance and making the Arctic Council a more relevant and future-oriented forum.”[4]

It is, however, important to keep in mind that the five Asian observer states are by no means similar Arctic or polar actors. For example, Japan stands out for its long polar history: It was the only Asian country among the original signatories of the Antarctic Treaty in 1959 and it was probably the first Asian country to establish a national polar institute. Singapore on the other hand, is the only country among the Arctic five to not yet have an official Arctic policy and does not have a research station in the Arctic, while India is the only country among the Asian observer without an Arctic ambassador. It is clear that the Arctic engagement and “profile” of the Asian five varies greatly.

Map: Arto Vitikka, Arctic Centre, University of Lapland

Geopolitical Changes and their Impact on Arctic Cooperation

The differences between the Asian five have become more important since Russia´s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 due to the rising significance of alliance politics. The phrase “likeminded countries” has become prominent in international forums, and it has also become increasingly common to talk about a “divided Arctic” or “two Arctics,” referring to the deep divide between the enormous Russian Arctic and the other Arctic states. While Japan, Singapore and South Korea were quick to condemn the invasion and to announce sanctions against Russia, India has adopted “strategic neutrality” against Russia and China is widely seen as an ally of Russia, although the relationship is complicated. Recently, joint military exercises in the Arctic between Russia and China have strengthened the image of a close partnership and caused increased military tension across the Arctic, putting both NATO and the United States on alert.

This development has negatively affected the image of China especially. For example, surveys in both Iceland and Sweden in the past few years demonstrate a growing wariness of Chinese investments and cooperation with China.[5] Meanwhile, the surveys show positive interest in cooperating with Japan. The Swedish surveys also look at attitudes towards India which, somewhat like China, is by many seen as a country that does not act “responsibly internationally” or “respects human rights.”[6] This general development has also influenced the willingness of Nordic states to engage in Arctic collaboration with different Asian states. A recent study by Ingvarsdóttir and Hauksdóttir (2024) demonstrates how the interest in Arctic cooperation with China has cooled significantly in recent years, with China´s research activities in Iceland increasingly being discussed in a security context.[7] The study also demonstrates that the same type of research by Japanese scientists has not raised any concern.

This development has negatively affected the image of China especially. For example, surveys in both Iceland and Sweden in the past few years demonstrate a growing wariness of Chinese investments and cooperation with China.[5] Meanwhile, the surveys show positive interest in cooperating with Japan. The Swedish surveys also look at attitudes towards India which, somewhat like China, is by many seen as a country that does not act “responsibly internationally” or “respects human rights.”[6] This general development has also influenced the willingness of Nordic states to engage in Arctic collaboration with different Asian states. A recent study by Ingvarsdóttir and Hauksdóttir (2024) demonstrates how the interest in Arctic cooperation with China has cooled significantly in recent years, with China´s research activities in Iceland increasingly being discussed in a security context.[7] The study also demonstrates that the same type of research by Japanese scientists has not raised any concern.

Japan's Activities in the Arctic

Japan has for many decades been an active contributor to and participant in Arctic science. Currently Japan has physical research stations or facilities for Arctic science in for example, Canada, Iceland and Svalbard (Norway), as well as various collaborations in the Arctic. Japan has also stepped-up its involvement in Arctic diplomacy and Icelandic-Japanese relations are a good example of that development. In 2015, Japan chose the Arctic Circle Assembly (ACA) in Reykjavík as the main international platform to announce its first official Arctic Policy. In 2018, then Foreign Minister Taro Kono visited the ACA and delivered one of the keynote speeches, and in 2019 Japan and Iceland announced that they would co-host the third Arctic Science Ministerial (ASM3) which was held in 2021 with the participation of 27 ministers of science (or their representatives) from around the world. Most recently, in March 2023, The Arctic Circle joined forces with the Sasakawa Peace Foundation and The Nippon Foundation to host the Arctic Circle Japan Forum[8] in Tokyo. Four ministers and two former ministers attended the Forum, signalling the growing importance of Arctic diplomacy for Japan. As written in an article in Ocean Newsletter by former President of Iceland Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson last year, the Forum was attended by over 300 participants from 25 countries, “thus making it unique among Arctic gatherings in Asia.”[9]

Representatives of the “Asian Five” at the Arctic Circle Japan Forum in spring 2023

The next phase in Japan´s Arctic engagement

2025 will be a big year for Japan in the Arctic. First, in March 2025, Japan´s Arctic Challenge for Sustainability II (ArCS II)[10] project is scheduled to end after five years. The project involves many of Japan´s finest universities and research institutions, and a large network of scholars. It will be interesting to see what shape the follow-up project is going to take. Second, in 2025 it has been 10 years since Japan launched its first official Arctic Policy. This milestone gives an interesting opportunity to look back on the first decade, review Japan´s engagement and think ahead. Third, important planning and preparations will take place in 2025 to get ready for the launch of Mirai II, Japan´s new research vessel for the Arctic with icebreaker capabilities.

Overall, the year 2025 will be significant for Japan as it advances into the next phase of Arctic science and diplomacy. The pillars of Japan´s Arctic Policy are science, environment & climate, and rule of law. In the current geopolitical landscape, Japan´s Arctic cooperation - towards both other Asian states and its partners in the Arctic - is probably more important than ever.

Overall, the year 2025 will be significant for Japan as it advances into the next phase of Arctic science and diplomacy. The pillars of Japan´s Arctic Policy are science, environment & climate, and rule of law. In the current geopolitical landscape, Japan´s Arctic cooperation - towards both other Asian states and its partners in the Arctic - is probably more important than ever.

[1] Canada, Denmark (including Greenland and the Faroe Islands), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States

[2] Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden

[3] Solli, P. E., Wilson Rowe, E., & Yennie Lindgren, W. (2013). Coming into the cold: Asia's Arctic interests. Polar Geography, 36(4), 253-270, p. 261. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2013.825345

[4] Lunde, L. (2014). The Nordic embrace: Why the Nordic countries welcome Asia to the Arctic table. Asia Policy, 18(1), 39-45, p. 39.

[5] See reports by Silja Bára Ómarsdóttir from 2021 and 2023 about Icelanders’ attitudes towards foreign affairs, and the Asian Barometer reports by Nicholas Olczak from 2022 and 2024.

[6] Olczak, N. (2024). The Asian Barometer 2024: Measuring the Swedish public’s views of China, India and Japan. Swedish Institute of International Affairs.

[7] Ingvarsdóttir, K., & Hauksdóttir, G. R. Th. (2024). Science diplomacy for stronger bilateral relations? The role of Arctic science in Iceland’s relations with Japan and China. The Polar Journal, 14(1), 314–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2024.2342114

[8] The annual forums are an offspring of the Arctic Circle Assembly and take place outside Iceland. This was the first forum to take place in Japan.

[9] Grímsson, Ó. R. (2023, July 20). The Role of the Arctic Circle and the Success of the Japan Forum. Ocean Newsletter No. 551.

[10] ArCS II is Japan´s flagship project for Arctic research. It runs from 2020-2025.

[2] Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden

[3] Solli, P. E., Wilson Rowe, E., & Yennie Lindgren, W. (2013). Coming into the cold: Asia's Arctic interests. Polar Geography, 36(4), 253-270, p. 261. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2013.825345

[4] Lunde, L. (2014). The Nordic embrace: Why the Nordic countries welcome Asia to the Arctic table. Asia Policy, 18(1), 39-45, p. 39.

[5] See reports by Silja Bára Ómarsdóttir from 2021 and 2023 about Icelanders’ attitudes towards foreign affairs, and the Asian Barometer reports by Nicholas Olczak from 2022 and 2024.

[6] Olczak, N. (2024). The Asian Barometer 2024: Measuring the Swedish public’s views of China, India and Japan. Swedish Institute of International Affairs.

[7] Ingvarsdóttir, K., & Hauksdóttir, G. R. Th. (2024). Science diplomacy for stronger bilateral relations? The role of Arctic science in Iceland’s relations with Japan and China. The Polar Journal, 14(1), 314–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2024.2342114

[8] The annual forums are an offspring of the Arctic Circle Assembly and take place outside Iceland. This was the first forum to take place in Japan.

[9] Grímsson, Ó. R. (2023, July 20). The Role of the Arctic Circle and the Success of the Japan Forum. Ocean Newsletter No. 551.

[10] ArCS II is Japan´s flagship project for Arctic research. It runs from 2020-2025.