Ocean Newsletter

No.597 September 20, 2025

-

The Tokyo International Conference on African Development and the Sustainable Blue Economy

KOBAYASHI Masanori (Senior Research Fellow, Sasakawa Peace Foundation)

With the cooperation of the Nippon Foundation and the Sasakawa Africa Association, the Sasakawa Peace Foundation held four high-level expert meetings since the summer of 2024, bringing together executives from Japanese government agencies and private companies. Following consultations with the African Diplomatic Corps in Tokyo, we have compiled a set of recommendations that were submitted to the Japanese Foreign Minister. We advanced discussions at the eminent persons’ meeting in July and the summit meeting in August. Based on the discussions, we intend to promote effective collaboration and advance Japan-Africa cooperation in the field of the sustainable blue economy.

-

Decarbonisation Efforts to Mitigate Climate Change Impacts in Southern Africa

Nwabisa MATOTI (Director: Strategic Projects and Internationalisation, South African International Maritime Institute)

Southern African countries—Namibia, Angola, Mozambique, and South Africa—are implementing measures to transition towards alternative fuels and renewable energy. The journey towards decarbonisation brings multiple challenges for African countries that have largely depended on fossil fuels—including constraints in infrastructure, finance, and community consultation and buy-in—and collaborative efforts as well as effective partnerships between Africa and other regions are key for effective climate change mitigation.

-

Calling for concerted actions to avert the impending climate-driven marine food security crisis in the Western Indian Ocean (WIO)

Michael ROBERTS (Professor, Nelson Mandela University (South Africa) and University of Southampton (United Kingdom))

In the Western Indian Ocean (WIO), ocean warming and marine heat waves are causing declining fish catches across the region, and ocean and coastal ecosystems are projected to collapse within 15 years, leading to a substantial reduction in marine food available for human consumption. To avert this climate crisis, international exposure and leadership are essential. Going forward, through the hosting of two international Summits, scientific evidence will be delivered to WIO governments and international institutions, and an international Mitigation Plan of Action for urgent implementation will be formulated.

-

The History and Future of JICA's Fisheries Project in Senegal

ISHII Jun (Former Junior Specialist, Agriculture and Rural Development Group I, Team II, Economic Development Department, JICA)

The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) has been implementing fisheries cooperation projects in Senegal for approximately 50 years. JICA has achieved remarkable results, particularly in joint management between fishermen and the government through technical cooperation, and these efforts have been expanded to neighboring countries. Based on the JICA Cluster Project Strategy "Promoting the Fisheries Blue Economy" formulated in 2024, a new cooperative project will be launched in June 2025 to improve distribution and sales, contributing to the enhancement of fishermen's livelihoods and promoting the fisheries blue economy in West Africa, primarily in Senegal.

-

Increasing Environmental Awareness in Madagascar

IIDA Taku (Professor, National Museum of Ethnology)

Increasing pressure on fisheries resources due to global climate change and modernization is also affecting Madagascar, a country far distant from Japan. In rural areas of Madagascar, the information environment is different from Japan, so trust in science is not as high. However, there are high expectations for science. To convey this nuance, this article discusses environmental conservation efforts by the people of Madagascar.

Calling for concerted actions to avert the impending climate-driven marine food security crisis in the Western Indian Ocean (WIO)

A climate-food security crisis in WIO

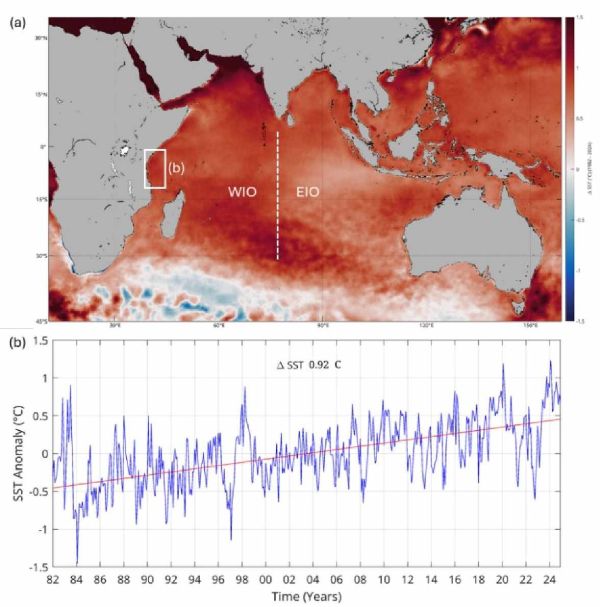

Ninety per cent of global warming occurs in the oceans. This has resulted in more than 300% increase in the ocean’s internal heat in the upper 800 m since records began in 1955. The last 10 years have been the warmest decade with 2024 the warmest year on record and 2025 will follow suit. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects that global temperatures will likely rise by more than 1.5°C to 2°C this century, and in some scenarios, by as much as 3.3°C to 5.7°C by the end of the century. There is little doubt the ocean will continue to warm. Satellite data show the Indian Ocean is not escaping this warming trend with the western half heating unusually fast — a phenomena known as heating amplification (Fig. 1).

The Western Indian Ocean (WIO) comprises nine countries, four of which are islands –Seychelles, Mauritius, Comoros and Madagascar. The others – Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, and the eastern side of South Africa – are coastal. All are DAC listed, with Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, Madagascar and Comoros classified as Least Developed and most Heavily Indebted Poor Countries. Covering some 30 million km2, the WIO area is equivalent to 8.1% of the global ocean surface, with a total coastline (because of the many islands) over 15,000 km. Of the combined WIO population of 260 M, about 60 M people live on the shoreline and are highly dependent on the ocean for food security and livelihoods ― second only to the Bay of Bengal (BoB) with 200 M people living on its shores and deltas. WIO coastal dwellers live in poor coastal communities, foraging from marine ecosystems. WIO is a global biodiversity hotspot with mangroves, seagrass beds, salt marshes, sandy beaches,headlands proliferate. These play a vital role adjacent to coral reefs as breeding and nursery grounds for many species of fish, cephalopods and marine animals. Artisanal fisheries, a core activity of coastal dwellers, are strongly dependent on these ecosystems. But ocean warming, including marine heat waves (MHWs), are already adversely impacting these habitats and ecosystems, especially widespread on corals, and fish catches are declining everywhere. Offshore, rising sea surface temperatures recorded over the last 100 years are shown to be coincident with decreasing phytoplankton production that supports the pelagic food webs and fisheries. Current models estimate that ocean and coastal ecosystems, as we know them, will collapse in WIO within 15 years, yielding far less food for human consumption.

The societal challenge in WIO is that these poor coastal communities are the most vulnerable and are unable to easily adapt to the quickening shifts in the ecosystems. Industrial fisheries in WIO (a large component of the blue economy) will similarly collapse not only lessening protein production and negatively impacting national food security but also causing economic and job losses — all further exacerbating coastal community hardship and impacting national and regional agendas of upliftment. The crisis is compounded by marine habitat destruction, concomitant droughts inland and rapidly increasing populations (~3%). The latter is extremely impactful. For example, Mozambique with a population of 34 M in 2024, will increase to 120 M by the end of the century. Even without climate change, it will be difficult to maintain sufficient food from the ocean. All told, WIO is facing a regional humanitarian crisis unseen before and of global plight. We refer to it as the WIO climate crisis.

Fig. 1: (a) change in the sea surface temperature (SST) over the Indian Ocean between 1982 and 2024 using OSTIO satellite data. Note the temperature scale also has cooling (blue).

(b) SST monthly timeseries for the white box off the east African coast. Total SST change

Urgent need for scientific information

While little can be done in the near-future in terms of reversing global warning ― WIO authorities, governments and international organizations need reliable information to enable timely planning and execution of mitigation measures. There is urgency. According to current ocean models, the first tipping point will occur around 2035 in the form of extended and intense MHWs.

The core focus of research needs to be around the WIO ecosystems. This includes defining location, their human coupling, their biodiversity status and functioning, drivers, rates of change, and importantly future functioning and productivity. Acquiring this knowledge requires tremendous scientific capability which is limited in WIO. Unlike terrestrial, marine ecosystems are not only immensely complex but also are remote and difficult to study. An array of state- of-the-art technologies (ocean models, marine robotics, satellites), and infrastructure (ships, moorings and laboratories) are required. Added, are high-end skills and sufficient scientists. These resources cannot be owned quickly ― especially by poor countries.

While it is important to know historical trends in the WIO ecosystems, it is equally important to understand future trends and tipping points. It is only with this knowledge that mitigation measures can be devised. Ultimately, a climate change road map is required for WIO.

Climate action leadership

The WIO climate crisis needs exposure and international leadership to avert this impending humanitarian emergency. The UK and Japan are key actors in international climate negotiations and initiatives such as the G7 and the UN Climate Change Conferences (COPs). Both countries are also significant contributors to international climate finance, supporting developing countries in their efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change. These roles are heightened given the USA has pullout of all climate treaties and fora. South Africa on the other hand plays a significant role in Africa as a regional economic powerhouse, a political influencer, and a key player in regional integration and conflict resolution, is a leading voice for the continent on global platforms and a major contributor to peace and security initiatives. Similarly, it is a key continental actor in international climate negotiations. All three countries have strong economies and world class scientific capabilities, and have experience in climate research, policy and adaptation. A combined leadership role in the WIO climate crisis will firmly enact respective commitments made at COPs, UNOCs, and others that advocate the advancement of global climate action.

As a start in addressing the WIO climate crisis, the UK and South Africa established the UK- SA Bilateral Chair in Ocean Science and marine Food Security in 2016. This 15-year Chair is co-hosted between Nelson Mandela University (NMU) and the University of Southampton and funded through the National Research Foundation (NRF) in South Africa and the Newton Fund of the UK. A key feature to roll out the research plan was to build an ‘Innovation Bridge- Regional Hub Network’ (IB-RHN) which formally connects these north-south universities with regional WIO partner institutions facilitating immediate access to skills, infrastructure, technology, funding and training. As the WIO climate crisis gains moment, it is now time for South Africa and the UK to strategically partner with Japan, expanding the IB-RHN. This will formidably increase scientific capability, speed knowledge progression and strategies for mitigation. I would like to call for Japan-UK-South Africa led concerted actions to avert the impending climate-driven marine food security crisis in the Western Indian Ocean (WIO), and urge G20 member countries to join in this collective joint endeavor.

Large grants to support the Chair research program have come from the UK’s Global Challenge Research Fund (GCRF) and the Newton Fund. The outcome from a new grant application to the UK International Strategic Partnership Fund (ISPF) is eagerly awaited to support the remainder of the research and ‘science into action’ plan. Certainly, the Ocean Policy Research Institute of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation (Japan) can play a pivotal role in translating science into action.

High end climate-ocean computer models

The main technical hindrance in exposing the WIO climate crisis and addressing it, is prototyping the future with timeframes of ecosystem tipping points. The current generation of computer models, measured against in situ observations, do not reflect reality very well, and hence cannot be trusted to project the future of WIO especially out to 2100. There is no doubt, with universal agreement, that the ocean is warming but it is important to understand that it will not necessarily warm the same everywhere. A trusted, detailed picture of the future must underpin any attempts to expose and deal with this impending crisis. It is here that the UK and Japan with their strong scientific capabilities and international leadership, and South Africa seen as a powerhouse on the African continent, can as a team, provide leadership and champion this regional/global challenge. Together they can bring about a ground-breaking, innovative phase that develops a new breed of powerful, AI-future-looking, Climate-Ocean- Ecosystem (COE) computer models. These will more reliably and accurately identify the future of the WIO and particularly the ecosystem ‘tipping points’ known as the WIO Climate Change roadmap. The new generation of COE computer models will enable us to review the seriousness of currently formulated scenarios of WIO warming (e.g., 70% decline in biodiversity and fisheries in WIO by 2100). This will enable governments and the international community to confidently take appropriate action.

Science into Action

The consequences of the climate-induced WIO warming (and amplification) are so serious that, despite incomplete research, engagement with the United Nations (UN) and African Union (AU) to host two international Summit meetings in the region has already begun. These will deliver the scientific evidence (Summit 1) to WIO governments and international institutions, and based on this, will formulate an international Mitigation Plan of Action (Summit 2) to be implemented with urgency. The first engagement took place in March 2024 in Cape Town with initial stakeholders — UNDP, UN-GESAMP, AU, British Council, British High Commission Pretoria, National Research Foundation (SA), International Panel for Ocean Sustainability (IPOS), University of Southampton, Nelson Mandela University, and University of Dar es Salaam (Tanzania). From a directive obtained at this meeting, further meetings supported by the ISPF and hopefully Japan will take place in 2025/26 to realise the Summits to be hosted in 2028/29. This timeframe gives space to generate new and more reliable future outlooks using the latest COE models. This ‘project driven’ solution using international structures to tackle a Global Challenge is novel and aimed at faster delivery than conventional UN/International protocols that progress slowly, mired by indecision. This ‘project-driven’ tactic actions the latest statement released by former UN secretary-general Ban Ki Moon, now Deputy Chair of The Elders, “We need to see an urgent change of direction in global decision-making” (5 March 2024).