Ocean Newsletter

No.575 July 20, 2024

-

Promoting Literacy in Ocean Dynamics through Offshore Drilling

MORONO Yuki (Principal Researcher, Geomicrobiology Group, Kochi Institute for Core Sample Research, JAMSTEC / Director, Japan Drilling Earth Science Consortium: J-DESC)

To contribute to the achievement of ocean-related missions set forth in the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science, the Japan Geodetic Drilling Science Consortium (J-DESC), as part of the International Ocean Drilling Program (IODP), is engaged in science that contributes to human society through the elucidation of the various mysteries hidden beneath the ocean floor, and aims to enhance literacy in marine science and ocean drilling science.

-

Advances in Bathymetric Technology and Ocean Floor Geoscience

OKINO Kyoko (Professor, Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, The University of Tokyo)

The development of multibeam bathymetry has enabled detailed imaging of seafloor topography and has greatly advanced ocean floor geoscience. In the future, it is necessary to expand the survey to areas of the ocean that have not yet been surveyed, and at the same time to become able to track temporal topographic changes before and after volcanic eruptions and earthquakes, and to establish a system for making basic data available to the public.

-

An Underwater Cultural Heritage Project in the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science

IWABUCHI Akifumi (Professor, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology (UNESCO UNITWIN Network for Underwater Archaeology))

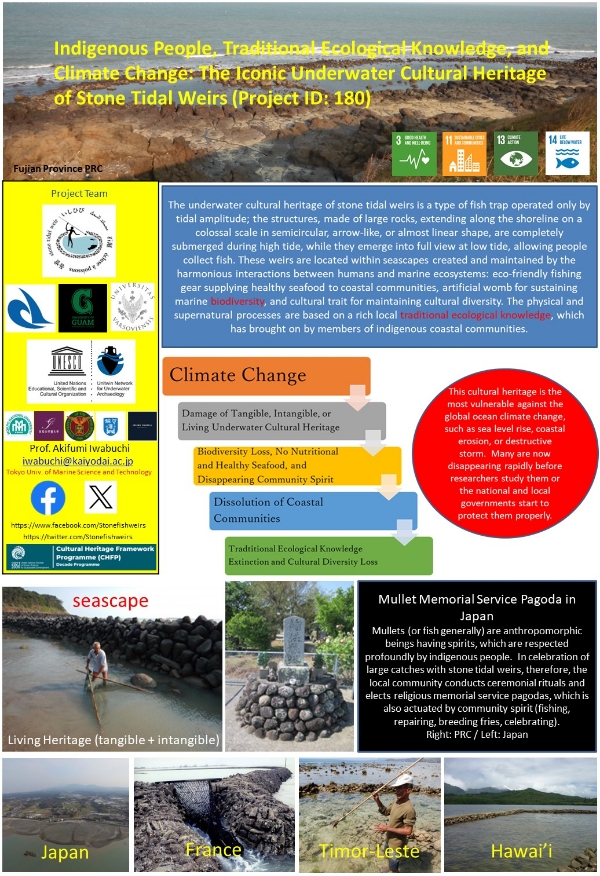

As of February 2024, the UN Decade of Ocean Science, which began in 2021, has 51 programs that were publicly solicited and 330 projects that are being put into action on the ground. One of the programs is the Cultural Heritage Framework Programme organized by the Ocean Decade Heritage Network, and one of its projects is "Indigenous People, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, and Climate Change: The Iconic Underwater Cultural Heritage of Stone Tidal Weirs ".

An Underwater Cultural Heritage Project in the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science

KEYWORDS

UN Decade of Ocean Science / Underwater Cultural Heritage / Stone Tidal Weirs

IWABUCHI Akifumi (Professor, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology (UNESCO UNITWIN Network for Underwater Archaeology))

As of February 2024, the UN Decade of Ocean Science, which began in 2021, has 51 programs that were publicly solicited and 330 projects that are being put into action on the ground. One of the programs is the Cultural Heritage Framework Programme organized by the Ocean Decade Heritage Network, and one of its projects is "Indigenous People, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, and Climate Change: The Iconic Underwater Cultural Heritage of Stone Tidal Weirs ".

Underwater Cultural Heritage Project

This underwater cultural heritage project has global-scale participation. It is led by Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, with participation from Chikushi Jogakuen University, the University of the Philippines, Mokpo National University in Korea, the University of Guam, the University of Warsaw in Poland, a state party to the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, Trinity College Dublin in Ireland, and Nelson Mandela University in South Africa, also a state party to the Convention. Amongst these participants, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, the University of Guam, and the University of Warsaw are member institutions of the UNESCO UNITWIN Network for Underwater Archaeology. The first in-person general assembly meeting was held at National Central University in Taiwan in June 2023, with full financial support from the Bureau of Cultural Heritage, Ministry of Culture. The Bureau of Cultural Heritage in Taiwan is an external government agency equivalent to the Agency for Cultural Affairs in Japan. The Taiwanese government has been allocating significant national budgets to underwater archaeology research as part of its ocean policy. It has shown strong interest in stone tidal weirs (ishihibi), a kind of fish barrier to catch sea creatures along the intertidal zone, which are a typical example of underwater cultural heritage defined by the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. In Taiwan, these weirs are found not only in the northwest of mainland Formosa, but a concentrated distribution can also be seen in the Penghu Islands located in the Taiwan Strait. In particular, those in the Penghu Islands are of a rare scale and quantity, even globally, and the Taiwanese government has been selecting them as World Cultural Heritage candidates.

The oldest historical record of stone tidal weirs in Taiwan dates back to 1696. Incidentally, the oldest historical document of such weirs in Japan is the “General Report on the Villages of Shimabara Fief” from 1707. With the exception of Taiwan, however, few countries have designated the fishing gear of stone tidal weirs as a subject of protection and conservation as part of their marine policy. In mainland China, Japan, and some Southeast Asian countries, rapid coastal development and ocean climate change have destroyed these weirs, creating the risk that they will disappear before being adequately surveyed and recorded by researchers. This is also because, despite the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage not mentioning the term shipwreck, most government officials equate underwater cultural heritage with shipwrecks.

The oldest historical record of stone tidal weirs in Taiwan dates back to 1696. Incidentally, the oldest historical document of such weirs in Japan is the “General Report on the Villages of Shimabara Fief” from 1707. With the exception of Taiwan, however, few countries have designated the fishing gear of stone tidal weirs as a subject of protection and conservation as part of their marine policy. In mainland China, Japan, and some Southeast Asian countries, rapid coastal development and ocean climate change have destroyed these weirs, creating the risk that they will disappear before being adequately surveyed and recorded by researchers. This is also because, despite the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage not mentioning the term shipwreck, most government officials equate underwater cultural heritage with shipwrecks.

Poster at the 2024 Ocean Decade Conference in Barcelona

Sustainable Development Goals

The stone tidal weir project of UN Decade of Ocean Science does not merely aim to protect and preserve the stone tidal weir, which is an ancient and unusual fishing gear. The project also aims to be a symbolic milestone connected to the future of the ocean and humanity, closely related to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 3, 11, 13, and 14.

SDG3: "Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages" might initially appear unrelated to weirs, but the focus here is on the fishery resources they provide to the local community. Western-style processed foods, which are being introduced worldwide, are taking the place of traditionally caught fish and shellfish and often have a negative impact on the health of local residents. Furthermore, it is also a common understanding that protecting and preserving traditional ecological knowledge and local cultural heritage contribute to the mental well-being of residents.

The weirs naturally fall under the cultural heritage focus of "Sustainable cities and communities," a sub-target of SDG11: "Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable". This is linked to the sustainability of healthy coastal communities, as per SDG3.

However, SDG13: "Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts" is the core of this UN project. The weirs can only catch fish and shellfish through tidal differences. Even a slight increase in sea level would render them ineffective as fishing gear. If they collapse due to destructive storms or coastal erosion, moreover, it becomes challenging to restore them in case local communities have been weakened.

The involvement of stone tidal weirs in marine biodiversity is also gaining increasing attention as part of SDG14: "Life Below Water". Local residents have preserved the traditional ecological knowledge, that by constructing stone tidal weirs the sea is regenerated and the harvest and variety of fish and shellfish increase.

SDG3: "Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages" might initially appear unrelated to weirs, but the focus here is on the fishery resources they provide to the local community. Western-style processed foods, which are being introduced worldwide, are taking the place of traditionally caught fish and shellfish and often have a negative impact on the health of local residents. Furthermore, it is also a common understanding that protecting and preserving traditional ecological knowledge and local cultural heritage contribute to the mental well-being of residents.

The weirs naturally fall under the cultural heritage focus of "Sustainable cities and communities," a sub-target of SDG11: "Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable". This is linked to the sustainability of healthy coastal communities, as per SDG3.

However, SDG13: "Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts" is the core of this UN project. The weirs can only catch fish and shellfish through tidal differences. Even a slight increase in sea level would render them ineffective as fishing gear. If they collapse due to destructive storms or coastal erosion, moreover, it becomes challenging to restore them in case local communities have been weakened.

The involvement of stone tidal weirs in marine biodiversity is also gaining increasing attention as part of SDG14: "Life Below Water". Local residents have preserved the traditional ecological knowledge, that by constructing stone tidal weirs the sea is regenerated and the harvest and variety of fish and shellfish increase.

The 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage

It is clear that, based on the Sustainable Development Goals, protecting and preserving underwater cultural heritage, including stone tidal weirs, should be a high priority in marine policy. The Chinese government has incorporated underwater cultural heritage research into national policy and is dedicated to its promotion nationwide. Taiwan and Korea are also making strong progress. Japan and North Korea are the only countries in East Asia that do not have specialized departments or dedicated national civil servants for underwater archaeology or marine culture within their government agencies. This is evidence that marine culture has become a keyword amongst the marine policies of many countries, and it is a shared fact that underwater cultural heritage exerts influence not only on national identity but also in defining maritime territorial borders.

Meanwhile, the Federated States of Micronesia, which protects stone tidal weirs on Yap Island as a national unit, has ratified the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage and bases its operations on it. The country plans to designate the World War II shipwreck sites in Chuuk Lagoon (formerly Truk Islands) as World Cultural Heritage, and in parallel, the Japanese government is advancing the recovery of hazardous materials like heavy oil and the retrieval of submerged human remains from sunken vessels in the area. Regarding potential pollution from sunken vessels, on April 4th and 5th, 2024, the world’s first international conference was held in London, co-hosted by the ICOMOS International Committee on the Underwater Cultural Heritage, UNESCO, the Lloyd's Register Foundation, and others.

In order for stone tidal weirs, WWII shipwrecks, and submerged human remains to be discussed in an international context as underwater cultural heritage, and given the fact that in the discussion opinions take as their core the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, which has already been ratified by nearly 80 countries worldwide, ratification of this Convention by the Japanese government is an urgent necessity. The international treaty could become a pillar for the maritime nation of Japan, and since no other countries in East Asia have ratified it, Japan, with the widest exclusive economic zone, should play a leading role in the ocean policy marine culture.

Meanwhile, the Federated States of Micronesia, which protects stone tidal weirs on Yap Island as a national unit, has ratified the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage and bases its operations on it. The country plans to designate the World War II shipwreck sites in Chuuk Lagoon (formerly Truk Islands) as World Cultural Heritage, and in parallel, the Japanese government is advancing the recovery of hazardous materials like heavy oil and the retrieval of submerged human remains from sunken vessels in the area. Regarding potential pollution from sunken vessels, on April 4th and 5th, 2024, the world’s first international conference was held in London, co-hosted by the ICOMOS International Committee on the Underwater Cultural Heritage, UNESCO, the Lloyd's Register Foundation, and others.

In order for stone tidal weirs, WWII shipwrecks, and submerged human remains to be discussed in an international context as underwater cultural heritage, and given the fact that in the discussion opinions take as their core the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, which has already been ratified by nearly 80 countries worldwide, ratification of this Convention by the Japanese government is an urgent necessity. The international treaty could become a pillar for the maritime nation of Japan, and since no other countries in East Asia have ratified it, Japan, with the widest exclusive economic zone, should play a leading role in the ocean policy marine culture.

Conference on the Development of Global Standards for the Remediation and Assessment of Potentially Polluting Wrecks