Ocean Newsletter

No.535 November 20, 2022

-

On Promoting the Blue Economy in Africa

Cherif SAMMARI (Professor, The National Institute of Marine Sciences and Technology (INSTM))

The United Nations has declared the Decade of Ocean Science, and while the prospects for the Blue Economy in Africa are promising, the development and use of the ocean and its resources remains unchanged from days past, and coordination and synergy on the regional and international levels are lacking. In order to facilitate early implementation of blue economy policies it is important to adopt systems incorporating new concepts, which I hope to promote through regional and international cooperation.

-

Dr. Shizuo Ishiguro's Legacy at Nagasaki Marine Observatory Before His Departure to the U.K.

NAKANO Toshiya (Head, Nagasaki Ocean Academy, Nagasaki Marine Industry Cluster Promotion Association; Former Director, Nagasaki Meteorological Office)

In this article, I will use historical documentation to introduce the work of Dr. Shizuo Ishiguro (1920–2007) during his time at Nagasaki Marine Observatory. Dr. Ishiguro was known for his pioneering work in using analog electronic circuits to identify complex oceanic phenomena and would eventually move from Nagasaki Prefecture to the U.K. I would also like to reflect on his research, which remains unfaded even now, on secondary undulations (abiki) in Nagasaki Bay, and discuss expectations for future research.

-

Passing on a Beautiful and Productive Ocean to the Future

YADOMARU Kotoko (President, Change Our Next Decade / 3rd-year Student, Doctoral Program, Graduate School of Horticulture, Chiba University)

Change Our Next Decade is an organization of young people involved in a wide range of activities in the field of biodiversity conservation, aiming to "creating better society in living in harmony with nature.” Through trial and error, Change Our Next Decade continues to make policy proposals and conduct public awareness activities to resolve issues related to marine biodiversity. We will keep striving forward so that we can enjoy the bounty of the beautiful and productive ocean even throughout our future.

Dr. Shizuo Ishiguro's Legacy at Nagasaki Marine Observatory Before His Departure to the U.K.

[KEYWORDS] analog electronic circuits / abiki / UK National Institute of Oceanography (NIO)NAKANO Toshiya

Head, Nagasaki Ocean Academy, Nagasaki Marine Industry Cluster Promotion Association; Former Director, Nagasaki Meteorological Office

In this article, I will use historical documentation to introduce the work of Dr. Shizuo Ishiguro (1920–2007) during his time at Nagasaki Marine Observatory. Dr. Ishiguro was known for his pioneering work in using analog electronic circuits to identify complex oceanic phenomena and would eventually move from Nagasaki Prefecture to the U.K. I would also like to reflect on his research, which remains unfaded even now, on secondary undulations (abiki) in Nagasaki Bay, and discuss expectations for future research.

What Nagasaki Marine Observatory’s Records Tell Us about Dr. Ishiguro

Nagasaki Port celebrated its 450th anniversary in 2021. As part of these celebrations, the Marine Education Symposium: From Nagasaki to the World, Connecting Nagasaki and the World with the Sea – Remembering the Achievements of Dr. Shizuo Ishiguro, was held at the newly opened Dejima Messe1. As many readers may know, Dr. Shizuo Ishiguro in the title of this article refers to the father of Mr. Kazuo Ishiguro, winner of the 2017 Nobel Prize in Literature. Although there is detailed literature2 available on Dr. Ishiguro’s accomplishments, I believe there is much still unknown. Therefore, in hopes of spurring more interest in Dr. Ishiguro, I would like to introduce his research activities using data and other materials remaining at the Nagasaki Marine Observatory, where he worked before moving to the U.K. Incidentally, the current staff from the observatory and former staff living in Nagasaki were interviewed shortly after Mr. Kazuo Ishiguro won the Nobel Prize for Literature. One of these former staff members said that when Dr. Ishiguro and his son left for England, he went to Nagasaki Station to see them off. But unfortunately, Mr. Kazuo Ishiguro was just five years old at the time and does not remember this event.

According to the records of Dr. Ishiguro still kept at the observatory, he graduated from Meiji College of Technology (MCT) (now Kyushu Institute of Technology), served the Army and other branches of government, and then joined the Japan Meteorological Agency after the war. In 1948, he was transferred from the Central Meteorological Observatory Research Institute (now the Meteorological Research Institute of the Japan Meteorological Agency) to the Nagasaki Marine Observatory (now the Nagasaki Meteorological Office) (Photo 1). In 1958 during his tenure, he received a degree from the Faculty of Science at the University of Tokyo. In 1960, he took a leave of absence from the Meteorological Agency to go to the National Institute of Oceanography in the U.K. He eventually resigned from the Meteorological Agency in March 1962. There are also records of patents and utility models, which give a sense of the potential of the observatory of the time, not to mention of Dr. Ishiguro himself. My first assignment was at the Nagasaki Marine Observatory’s Marine Division. However, I am ashamed to say that I first learned of Dr. Ishiguro from an article by Professor Emeritus Hisashi Mitsuyasu from Kyushu University that appeared in Vol. 7, No. 1, of the Oceanographic Society of Japan (JOS) News Letter (2017), before news of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Nobel Prize in Literature. Dr. Ishiguro composed the “Nagasaki Marine Observatory Song,” which was sung on the anniversary of the observatory's founding and other occasions, but I never knew who the composer was.

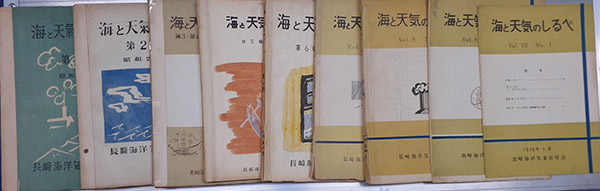

The observatory also had the Nagasaki Marine Observatory Association. A record of the association’s activities remains in the publication Umi to Tenki no Shirube [A Guide to the Sea and Weather] (Photo 2). Dr. Michitaka Uda's (the observatory's first director) article “Shiome no Hanashi” [Story of Ocean Fronts] appeared in Vol. 1, Issue 1, and Dr. Ishiguro's article “Rajiozonde no Hanashi” [Radiosonde Story] appeared in Issue 39. Dr. Ishiguro continued to make numerous contributions to the publication, which seems to have been the center of his activities. Writing takes a certain amount of getting used to, but I am impressed at his success despite having to handwrite everything at the time.

Dr. Ishiguro is mentioned in a section on Nagasaki Marine Observatory in the chapter "Nihon Kaiyo Kenkyu no Hajimari” [The Dawn of Marine Research in Japan] in Kaiyo Kenkyu Hattatsushi [History of the Development of Marine Research] (Michitaka Uda, Tokai University Press, 1978). The section states, "…Shizuo Ishiguro and his team invented equipment such as self-recording electron tube wave gauges and current gauges, and worked hard to solve the difficult problem of preventing marine accidents at Hirado Strait using model experiments and actual measurements of currents and waves, for which he and the team received the Minister for Transport's Prize.” This reveals that Dr. Ishiguro was developing equipment and conducting experiments using what was available to correctly understand complex ocean phenomena at a time without computers. Of particular note was his tidal current analysis of the Hirado Strait, which began with the construction of an accurate model of the topography, his study of secondary undulations in Nagasaki Bay (called abiki3), and his model experiments to reproduce the tide levels of the Ariake Sea tide using automatic controls. These research results led to him moving to the U.K . Dr. Ishiguro wrote numerous papers and reports, but there are also some documents where his name is not listed as an author, even though he must have been involved in the experiments and research. Although it is evident that he performed a great deal of work, I am curious about his life at the time.

■ Photo 1: Dr. Shizuo Ishiguro (front row, left) during his tenure at Nagasaki Marine Observatory. His experimental equipment can be seen in the background. (Photo courtesy of Mr. Morikawa (back row, left), a former member of Nagasaki Marine Observatory)

■ Photo 1: Dr. Shizuo Ishiguro (front row, left) during his tenure at Nagasaki Marine Observatory. His experimental equipment can be seen in the background. (Photo courtesy of Mr. Morikawa (back row, left), a former member of Nagasaki Marine Observatory)

■Photo 2: The cover of Umi to Tenki no Shirube [A Guide to the Sea and Weather] by the Nagasaki Marine Observatory Association. Volumes 1 (left, 1948) through 10 (1956). The third volume combines the third and fourth editions. The association was disbanded in 1957 as part of organizational development.

■Photo 2: The cover of Umi to Tenki no Shirube [A Guide to the Sea and Weather] by the Nagasaki Marine Observatory Association. Volumes 1 (left, 1948) through 10 (1956). The third volume combines the third and fourth editions. The association was disbanded in 1957 as part of organizational development.

Dr. Ishiguro's Abiki Research and Future Outlook

Finally, I would like to write about Dr. Ishiguro's most significant achievement at Nagasaki Marine Observatory: his research on the abiki phenomenon. The phenomenon of water oscillating with a characteristic periodicity in harbors and lakes is called a seiche. However, in harbors, they are also called secondary undulations because they are observed in conjunction with the tides. The secondary undulations observed in Nagasaki Bay, amplified through eastward propagating water level changes caused by micro-pressure fluctuations over the continental shelf in the East China Sea, are called abiki in the Nagasaki dialect. Based on the shape of the waves of water level during abiki seen in observations and hydraulic model experiments, Dr. Ishiguro reproduced their shape using analog electronic circuits while considering the topography of Nagasaki Bay. These results truly reveal how insightful his ideas were. His research is still cited more than half a century later as the basis for the mechanism behind abiki generation as we currently understand it using digital computers and atmospheric field analysis.

Incidentally, the most memorable abiki for the author was the second largest ever, which occurred in 1988. Shortly after I arrived at work, the water level began to change. I went down the hill from the observatory and confirmed that the water level was indeed going up and down at the quay wall at about 25-minute intervals. After that, the changes became smaller. Then, around noon, the water level began to change again, and this time several of us went to the mouth of the Urakami River with cameras. I remember how excited we were to see the seawater moving up the river. The photos on the Japan Meteorological Agency’s website4 were taken at that time.

I have become curious about why there have been no abiki of more than 150 cm recently. In March 2019, an abiki was at its highest level just as the spring and high tides coincided but the maximum total amplitude, at just 108 cm, was not even in the top 10 biggest abiki. I am intrigued whether this is due to changes in topography due to the development of Nagasaki Port and other factors, or whether micro-barometric pressure fluctuations are becoming more uncommon in the East China Sea. Dr. Ishiguro and his colleagues also studied how port facilities could reduce secondary undulations. If port development is a factor in this change, could simulations clarify this by using historical and recent topographic data? If so, we may gain valuable insights into disaster prevention and risk management for the future development of Nagasaki Port. The latter would also require a study of changes in atmospheric fields. In any case, there are many unanswered questions regarding information on abiki, leaving high hopes for future research. (End)

- 1.The 72nd Maritime Education Symposium, organized by the Maritime Education Promotion Committee of the Japan Society of Naval Architects and Ocean Engineers and co-sponsored by the Nagasaki University Organization for Marine Science and Technology and others.

https://nagasaki-kaiyou.jp/ - 2.Kazumasa Oguri (2018) “Ishiguro Shizuo Hakase no Gyoseki” [The Work of Dr. Shizuo Ishiguro] in Umi no Kenkyu (Oceanography in Japan), No. 27, pp. 189 - 216 / (2022) “Analog Denshikairo ni yoru Choi to Kocho no Yosoku” [Predicting Tides and Storm Surges Using Analog Electronic Circuits], The Nihon Butsuri Gakkaishi (Butsuri), No. 77 (9), pp. 632 - 635.

- 3.Ryohei Okada, "The Abiki Secondary Undulation" No. 218 of this Newsletter (September 5, 2009)

https://www.spf.org/opri/newsletter/218_2.html - 4.Nagasaki Meteorological Office “Secondary Undulations (abiki)”

https://www.jma-net.go.jp/nagasaki-c/shosai/knowledge/abiki/abiki.html