Ocean Newsletter

No.526 July 5, 2022

-

Realizing Undersea IoT: Underwater Optical Wireless Communication

NISHIMURA Naoki

Head, Magnetic Devices Section, Aircraft Equipment Division, Shimadzu CorporationThe ocean energy field is gaining more and more attention as a means towards achieving carbon neutrality, with offshore wind energy being a leading example. In order to efficiently make advances in ocean development going forward, we would need underwater IoT (visual control) to give us a clear understanding of undersea conditions. It is therefore essential that we have the equipment for high-speed wireless communications underwater. This article introduces the technology for visible light wireless communications that my company has been developing for this purpose. -

What We Have Learned about the Reproductive Ecology of Japanese Cormorant: Egg Laying by the Fishing Cormorants of the Uji River, and Follow-up Findings

UDA Shuhei

Associate Professor, Department of Advanced Studies in Anthropology, National Museum of EthnologyIn May 2014, one of the Japanese cormorant of the Uji River laid its eggs there. In the history of cormorant fishing in Japan - said to stretch back over 1,300 years - this was an extremely unusual event. Spurred on by this development, the cormorant fishermen continued their near-annual captive breeding program, resulting in the hatching to date of 17 chicks. Notably, almost no studies had been conducted to that point about the reproductive ecology of Japanese cormorant, so a joint research project was launched to better understand this. After five years of ongoing study, we have come to know much more about the various aspects of the reproductive ecology of Japanese cormorant, including their egg laying and growth process. -

Digital Applications and Deepening Its Use in Museums

TAKADA Koji

President, Marine and Museum LaboratoryOn April 8, 2022, the revised Museum Act was passed and approved in the plenary session of the House of Councillors, and discussions are being held regarding the informatization of museums before it is put into effect on April 1, 2023. With the announcement of the GIGA School Program on December 2019 and the surge of online interactions from the coinciding COVID-19 pandemic, we are also expecting greater digitalization of museum activities. Thus, in this article I would like to discuss the state of ocean education digitalization in museums, including aquariums.

What We Have Learned about the Reproductive Ecology of Japanese Cormorant: Egg Laying by the Fishing Cormorants of the Uji River, and Follow-up Findings

[KEYWORDS] Egg laying/growth process/domesticationUDA Shuhei

Associate Professor, Department of Advanced Studies in Anthropology, National Museum of Ethnology

In May 2014, one of the Japanese cormorant of the Uji River laid its eggs there. In the history of cormorant fishing in Japan - said to stretch back over 1,300 years - this was an extremely unusual event.

Spurred on by this development, the cormorant fishermen continued their near-annual captive breeding program, resulting in the hatching to date of 17 chicks.

Notably, almost no studies had been conducted to that point about the reproductive ecology of Japanese cormorant, so a joint research project was launched to better understand this.

After five years of ongoing study, we have come to know much more about the various aspects of the reproductive ecology of Japanese cormorant, including their egg laying and growth process.

Second and third steps

In May 2014, a fishing cormorant of the Uji River in Uji City, Kyoto Prefecture, laid its eggs there. Cormorant fishing has a history of more than 1,300 years in Japan, and was once conducted at more than 100 locations. Many people were engaged in cormorant fishing for a living. However, I have come across no instances of the captive breeding of cormorants used for fishing (Japanese cormorant and great cormorants). According to Hiroaki KANI (1966, p. 167) *1 who compiled a history of cormorant fishing in Japan, cormorants “do not breed while under human management, so artificial incubation is not possible.” Also, Japanese cormorant fisherman and other stakeholders thought that cormorants did not lay eggs.

Despite this, one day a Japanese cormorant suddenly laid eggs by the Uji River. In an article for this Newsletter No. 357, (published June 20, 2015), I described this remarkable development as the “Uji River Cormorant Fishermen and the Japanese cormorant's ‘First Steps’.” By “first steps,” I meant that it was the first time that people had begun the captive breeding of sea cormorants. It signified the first step toward the Uji River cormorant fishermen breeding and then domesticating Japanese cormorant. Since then, they have continued the captive breeding of cormorants most years. In the process, they have faced many issues, such as eggs not hatching or a high death rate among chicks, but the fishermen have continued to learn from experience and refine their breeding techniques. They are also training for untethered cormorant fishing (which does not use a rope linking the bird to the cormorant fisherman) using cormorants. Moving on from this unanticipated first step, they are now beginning to take the second and third steps. This article will now look at what has been learned about the reproductive ecology of Japanese cormorant through studies since 2014, and the initiatives taken by cormorant fishermen based on those findings.

Techniques to encourage egg laying

Nesting platforms and materials installed in breeding hutches (April 2017, Uji City, Kyoto Prefecture)

Nesting platforms and materials installed in breeding hutches (April 2017, Uji City, Kyoto Prefecture)

Nesting materials such as rice straw and twigs - as well as the nests the birds used them to make - were present near the parent birds which laid eggs in May 2014. Noticing this, the cormorant fishermen inferred that the availability of nesting materials encouraged the birds to lay eggs, and so provided more nesting materials to the parent birds. The parent birds responded by starting to build nests with the new materials, leading to the laying of another five eggs. Based on this experience, the fishermen’s first steps in breeding efforts from the following year were to install nesting materials and platforms in breeding hutches (shown in the photograph above). The materials included rice straw, bamboo leaves, hemp-palm ropes, and the tips of bamboo brooms. When the materials were laid out for the birds, several pairs started building nests, and began laying eggs several days later. In fact, in 2015 two pairs laid a total of 13 eggs, in 2016 two pairs again laid 13 eggs, and in 2017 four pairs laid a total of 20 eggs. The average time from beginning to build a nest until laying eggs was 14.8 days. Considering that the clutch size (number of eggs laid per season) for a wild cormorant is three to four eggs, this number was exceeded in 2014.

Whenever a sea cormorant lays an egg, the cormorant fishermen remove it from the nest for monitoring in an incubator. After which - perhaps realizing that the egg is missing - the mother lays another egg two to three days later. Many aquatic birds typically lay more eggs until reaching their clutch size if an egg disappears after being laid; these are known as replacement clutch. Learning from their experience with the replacement clutch phenomenon, the cormorant fishermen were able to obtain more eggs per bird than the clutch size of wild Japanese cormorant.

Shedding light on the growth process

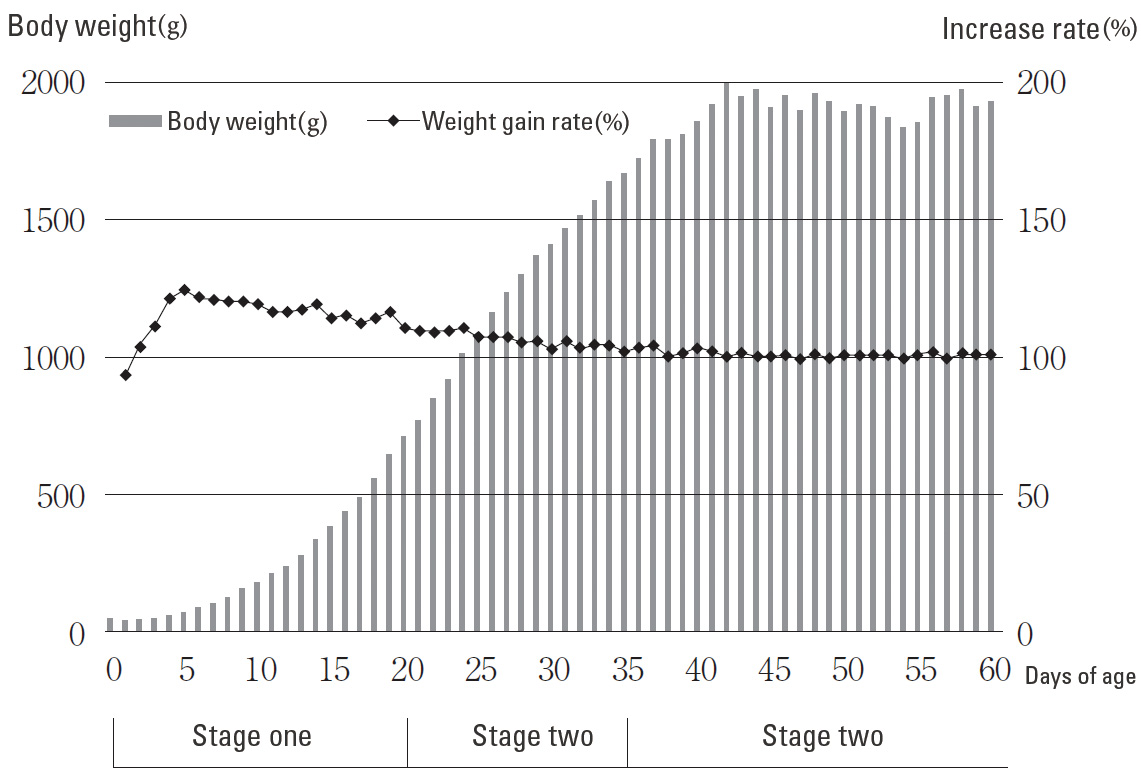

Japanese cormorant are altricial birds, or slow developers, meaning that after hatching their eyes are closed, their down feathers have yet to grow, and they are incapable of moving around on their own to obtain food. Therefore, raising them in captivity demands that breeders feed chicks by hand and carefully manage their body temperatures. This growth pattern is in stark contrast to precocial birds, which are capable of moving around soon after hatching. Through joint research with cormorant fishermen, the author recorded the growth process of Japanese cormorant, which are a distinctively altricious species. The chart shows the chicks’ body weights and weight gain rate (over the previous day) by the number of days from hatching. These records show that the chicks grow towards fledging in three broad stages.

Stage one is the rapid growth stage from hatching until around 20 days old. During this time, the weight gain rate averages 115% per day, and notably exceeds 120% from day four to ten. In fact, during this period they look significantly bigger after just one day of not seeing them. Such rapid growth after hatching is believed to be in order to quickly pass through the vulnerable early stages. The captive breeding of Japanese cormorant therefore requires significant effort and time in feeding the helpless chicks.

Stage two is the stable growth stage from 20 to around 35 days old. During this time, chicks gain significant amounts of weight, but at a slower rate, around 105% per day. The shapes of their wings and plumage gradually become distinct, and they become able to walk, albeit unstably. The environment in which they are reared is altered to suit the changes in their appearance and behavior. Stage three is the broadly stable stage from 35 days old onward. During this time, the birds only gain weight slowly - at 105% per day or less - and no clear changes are evident. Their contour feathers begin to appear as they grow toward fledging, and they can continuously flap their wings up and down. Juvenile birds likely use most of the energy they consume in growing plumage and muscles as well as in exercise. Through their daily feeding and rearing work, the cormorant fishermen have observed how cormorants grow from chicks to juveniles and then young birds. Based on this experience, they have adjusted factors such as the volume and type of food, rearing spaces, and hours the cormorants spend in the sun.

■ Changes in chicks’ body weights and weight gain rate (based on Uda, 2021)

■ Changes in chicks’ body weights and weight gain rate (based on Uda, 2021)

Motivations to continue captive breeding

In the breeding work, changes evident in the chicks were recorded daily until they were about 60 days old. The results obtained from 17 chicks were compiled into data by the number of days from hatching, providing insight into the changes common to each of the growth stages. It goes without saying, that the field surveys, which record in detail chicks’ body weights, food volumes, and changes in behavior daily over a period of years, are quite demanding. In addition, very few zoos either in Japan or overseas rear Japanese cormorant, and information about how to breed them is extremely scarce. Moreover, cormorant fishing in Japan has for many years used wild birds, so fishermen have no accumulated experience in captive breeding to draw on. In such a situation, recording the reproductive ecology of Japanese cormorant in detail will likely contribute to the revival of breeding techniques and enrichment of the environment*2 in which they are reared. Additionally, it is enjoyable to watch the chicks grow up while working to raise them, with every year bringing new discoveries. This enjoyment, fascination, and curiosity are just some of the drivers of the ongoing captive breeding of Japanese cormorant. Looking ahead, these breeding techniques will likely become essential in passing on Japan’s cormorant fishing culture to future generations. (End)

- *1“UKAI: Restore of Folk and Transmission” by Hiroaki KANI, Chuko Shinsho, 1966

- *2Enrichment of the environment refers to initiatives taken regarding the environment that animals are reared in to improve their health and welfare.

- Reference:“Cormorants and Humans: An Ornithological Folklore Study of Cormorant Fishing in Japan, China and North Macedonia” by Shuhei UDA, University of Tokyo Press, 2021