Mr. Nishida: The UN has reached a turning point. In January this year, the UN underwent restructuring as part of the broader reforms spearheaded by UN Secretary-General António Guterres, who assumed his position in January 2017. Under the peace and security architecture reform, the UN established the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA) and the Department of Peace Operations (DPO) replacing the Department of Political Affairs (DPA) and the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO). In terms of management of the UN, the former Department of Field Support (DFS) and the Department of Management (DM) were realigned into the new Department of Operational Support (DOS), to which you belong, and the Department of Management Strategy, Policy and Compliance (DMSPC). How will UN peacekeeping operations change as a result of these reforms?

Mr. Ito: The UN has undergone a number of organizational reforms to enhance the effectiveness and coherence of peace activities to deal with various conflicts, which are increasing in their complexity and degree of danger. The latest reforms were carried out in three areas, namely “peace and security,” “management,” and “development.” Recognizing the “primacy of politics,” the reforms for “peace and security” and “management” in particular have created departments that can take a more holistic approach toward sustaining peace while continuing efforts in conflict prevention. These departments were restructured and decision-making authority decentralized so that peace operations are swiftly provided with the support from headquarters when needed, but also delegated with greater authority to make decisions and initiate quick actions.

Prior to these reforms, from personal experience of having worked in DPA and in peacekeeping mission undergoing transitions, I had felt the limitation of having vertically organized regional divisions. For example, DPA was essentially responsible for monitoring and analyzing political developments of countries and regions around the world. However, once a UN peacekeeping mission was established in a country, DPKO would become the “lead department” and take over that responsibility from DPA. In this transition, the insights and information sources held by DPA, which had been monitoring the political developments of that country up to that point, could not be easily transferred to DPKO in their entirety.

One of the features of the peace and security architecture reform is the integration of regional divisions that had previously been run separately by DPA and DPKO. This elimination of redundancy means that each country or region has one director overseen by the region’s Assistant Secretary-General regardless of whether there is a peacekeeping mission, special political mission, or a UN country team in place. This allows for a whole-of-pillar approach and for information and analysis by both DPPA and DPO political officers to be comprehensively reported to senior management.

With regard to management reform, it should be viewed as a continuation of reform efforts which began with the reorganization of the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations in 2007. Department of Field Support (DFS), which in large part was the predecessor of DOS, was once part of DPKO providing operational support to peacekeeping missions. In 2007, operational support functions separated from DPKO and became DFS, a single entity responsible for provision of operational support not only to peacekeeping missions but also to special political missions (SPMs). The sudden increase in the number of missions to be supported by the same number of staff created the need to innovate and streamline support operations. Up until then, each individual mission had back-office functions such as human resources, budget and finance, administration, information and communication technology, logistics, etc. We centralized much of these functions to global and regional service centers, which provided standardized services to multiple missions in the respective regions.

The positive effect of this integration and innovation was recognized by the Secretary-General and member states. Consequently, as a result of the latest reform, DOS was made in charge of providing operational support for the UN Secretariat’s entire activities in addition to peacekeeping missions and SPMs.

Mr. Nishida: I see. So, the focus has shifted from operational support in every frontline site to global and regional management of various support functions to streamline operations. Secretary-General Guterres is also pursuing an initiative called “Action for Peacekeeping (A4P).” This new agenda calls for strengthening UN peacekeeping operations, improving the capabilities of dispatched troops, ensuring the safety of peacekeepers, and revitalizing activities designed to encourage greater commitment from member nations. Why has he chosen this timing to propose reforms to peacekeeping operations?

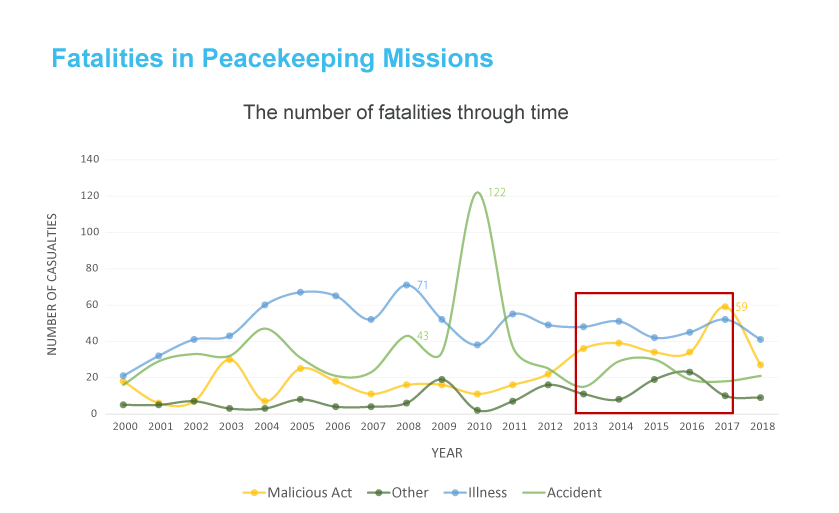

Mr. Ito: The direct trigger for this initiative was the increase in peacekeeper deaths from hostile acts. During the UN Security Council meeting on March 28, 2018, when the A4P initiative was unveiled, Secretary-General Guterres said it was “unacceptable” that 59 peacekeepers had been killed through malicious acts in 2017. He stressed the importance of ensuring the safety of peacekeeping operations; the necessity of realistic mandates and well-structured, well-equipped, and well-trained troops; and greater support for political solutions.

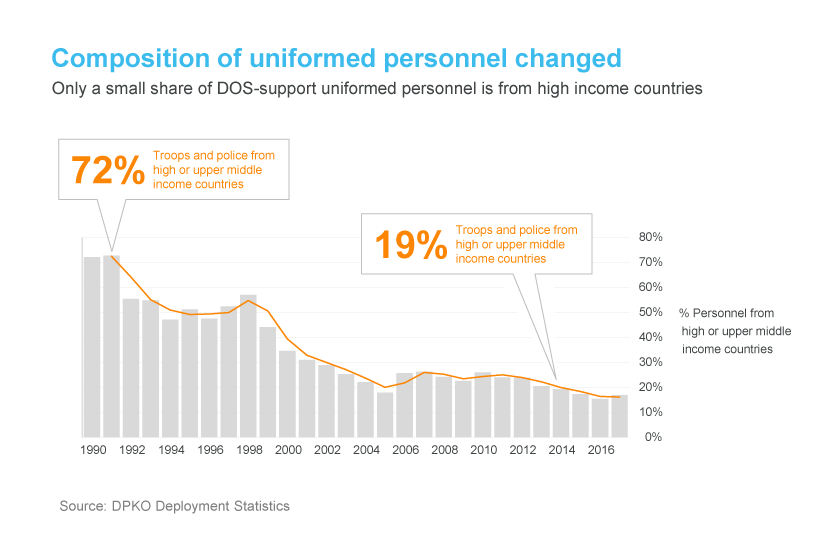

Another underlying factor for this reform was a major shift in the type of conflicts that required intervention, a change that has been underway since the end of the Cold War. Generally, conflicts being addressed by UN peacekeeping have evolved from conflicts between states to intrastate conflicts including civil wars and a mixture of civil war with regional conflicts. In addition, intervention by peacekeepers in non-permissive environments in countries and regions where peace processes were fragile or non-existent has highlighted the high security risks faced by the general population in peacekeeping host countries as well as by peacekeepers themselves. This may have contributed to the change in the composition of UN troops and police contributing countries. Developing countries deployed more troops and police to peacekeeping missions, eventually overtaking developed countries as major troops and police contributors (Figure 1).

As the scale of peacekeeping missions rose, the mandates given to them by the UN Security Council became more diverse and complex while also becoming more robust with the inclusion of protection of civilians responsibilities. Some of the peacekeeping missions were also growing more protracted, unable to accomplish many of the tasks assigned to them. Furthermore, there were even peacekeepers found to have sexually exploited or abused local women and children. Trust in the UN has been shaken in countries like the Central African Republic, where some troops became the perpetrators of sexual violence against the very people they were charged to protect.

Many of these issues could not be addressed by the UN Secretariat alone. It has become essential to renew collective commitment to strengthen peacekeeping by all UN peacekeeping partners including the member states, host countries, and regional organizations, which has resulted in the launch of the A4P initiative.