Ocean Newsletter

No.91 May 20, 2004

-

Formation of an Asian Network for Maritime Technology Education is a Matter of Urgency

Hiroaki Kobayashi Professor, Faculty of Marine Technology, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology / Selected Papers No.7(p.4)

A need to educate and evaluate seafarer's skills in an adequate manner has been pointed out in order to assure the conservation of the maritime environment and the safety of ship management. The present education status in Asia, where many seafarers appear one after another, as well as roles which Japan should play are pointed out.

Selected Papers No.7(p.4) -

AUV development in Japan and its future

Yuichi Shirasaki President, Marine Eco Tech Ltd.

Roles which underwater robots play in maritime investigations have become increasingly more important. At present, ROVs (Remotely Operated Vehicles) take an active part in various fields ranging from scientific explorations to offshore oil fields. In the future, it is expected that AUVs (Autonomous Underwater Vehicles) can bring us new discoveries and make it possible to perform new investigations that have been difficult in the past.

-

A movable "purification vessel"

Masaharu Fukue Doctor of Philosophy and Professor, Marine Civil Engineering, School of Marine Science and Technology, Tokai University

A purification vessel was built for the purpose of purifying seawater by converting from a barge (2,350 tons), and seawater purification experiments were performed in Kasaoka Bay of Okayama Prefecture and Ashiya Port of Hyogo Prefecture. The capacity of the purification of seawater is more than 6,000 tons per day, and more than 80% of the suspended solids were removed. Therefore, many kinds of problems caused by the suspended solids are expected to be solved by purification vessels.

Formation of an Asian Network for Maritime Technology Education is a Matter of Urgency

The need to educate seafarers and evaluate their skills properly has been pointed out in order to assure the conservation of the marine environment and the safety of ship management. In this study, current education conditions in Asia, where many seafarers are from, as well as the roles which Japan should play, are examined.

Introduction

It is said that more than half of the seafarers currently working for commercial ocean fleets in the world come from developing countries. About 80% of the vessels controlled by Japan are manned by seafarers from Asia. As a matter of course, they receive training from educational institutions for seafarers in their countries, and acquire their respective qualifications before boarding the vessels. However, problems with regard to the content of their education and to the assessment of their qualifications have occurred. The problems have resulted from the ambiguous descriptions to be found in international conventions.

World's current maritime technology education

As an international guideline for maritime technology*, there is the International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW); and each educational institution, as one of its goals, aims to conform to this international convention. But there have been major issues. To be specific, the STCW provides a list of skills required under the various conditions that vessels may encounter. However, as there are only general descriptions for conditions and skills, as well as qualification assessments, training methods for each item are left to the judgment of each educational institution. For instance, in the section on use of electronics for position measuring, which is an important skill for shipping control, it defines "an ability to measure a ship's position with the use of equipment" as a skill to be acquired, and prescribes that qualifications should be assessed based on a judgment whether "the manufacturer's guidelines and actual navigational conditions are followed." As a prescription for specific training, such wording is extremely ambiguous. As a result, each educational institution implements differently what is prescribed, so it is hard to say that trained seafarers' qualifications are uniform.

The EU also took this problem seriously, and established a large-scale exploratory committee called the Maritime Education and Training Network (METNET) with a fund from the EC, and activities aiming at the EU standardization of the quality of education for seafarers have begun.

Current Asian maritime technology education

In order to attempt an appropriate homogenization of seafarers' qualifications, it is necessary to understand correctly the fundamental concept of the STCW, to incorporate its required skills precisely with education and training, and implement qualification assessments. However, educational institutions in Asia have a tendency to set practical training situations directly from the content of the STCW. It is therefore difficult to analyze the skills necessary to achieve safe navigation, the basic concept of the STCW, to provide education and training, and to proceed with qualification assessments. When there is sufficient time for training, it can be provided for all the conditions assumed from the description of the STCW. However, unlike nautical educational institutions with improved curricula in advanced maritime countries, a recently increasing number of training institutions in developing countries often ends up failing to provide training for necessary skills. Faculties at the institutions also see this as a serious problem.

Photo 1: View of a ship handling simulator

Photo 1: View of a ship handling simulator

Future maritime technology education

European countries have recently formulated rules for various matters regarding safe navigation and are working towards a standardized navigational system. The European countries also think it is difficult to secure seafarers from their own countries for marine transportation and are concerned that the skills of less expensive seafarers will decline, prompting their desire for appropriate qualification assessments and formulation of standard procedures for ship management. However, the argument in Europe with regard to maritime technology is rather restricted by their own tradition, which places the highest emphasis on experience, a view, as regards navigational safety, that seems far from a rational approach based on scientific analysis. Under these circumstances, although most of the crews of the world's commercial ocean fleets are Asian manned, it is expected that the unified stance of the EU, as typified by METNET, will become stronger and their influence will increase enormously in the future.

The STCW recommends the use of effective means for training and gives particular importance to training with the use of simulators. However, although the use of simulators is advantageous in that environmental conditions can be set for carefully selected skills to be acquired through training, simulators are actually often used to replicate conditions similar to those of conventional on-ship training. This is due to the fact that conventional maritime technology education is simply being carried forward without modification.

Photo 1 shows a ship-handling simulator made in Japan and rated at the top of world standards.

Future direction for Japan

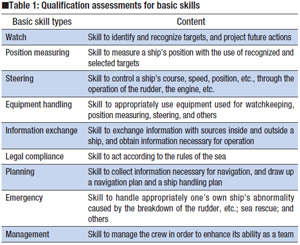

In order to enhance the safety of the world's and Japan's maritime transport, it is important to improve the quality of seafarers in Asia, and Asian countries are anxious to receive technological support, especially for education and training, from Japan. Japan's maritime technology education has long been highly regarded internationally, and recent education and qualification assessment methods proposed by Japan have also been evaluated highly in Europe. The proposed education and qualification assessment methods are characterized by the concretized content of the nine skills to be objects of training, as indicated in table 1. With the concretized content of the skills, efficient educational curricula were formulated, skills applicable for qualification assessment were clarified, and a systematic educational system was established.

Asian countries are not powerful enough to take action individually, and they expect Japan to take a leading role. It is now considered necessary to respond immediately. As an organizer, Japan will need to ask the individual Asian countries that now work separately to establish a network for education and training. Alliance with the respective Asian countries and Japan will be strengthened through technological cooperation with them, and it might become possible to establish an international influence equal to that of the EU. Through these efforts, the standardization of navigation systems can be carried out under the lead of Asian countries, rather than European, thus being more refletive of current conditions.

* Maritime technology is "technology related to maritime affairs." In a restricted sense, maritime technology includes vessels (equipment) and the navigation technology to achieve marine transportation.