Ocean Newsletter

No.596 August 20, 2025

-

Environmental Impact Assessment Obligations for Deep Seabed Mineral Resource Development

KANNO Naoyuki (Adjunct Lecturer, Hosei University)

In deep seabed mineral resource development, environmental impact assessments (EIAs) are essential to balancing development and environmental protection, and their implementation is mandatory under international law. This paper provides an overview of the EIA procedures established by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the international organization overseeing deep seabed mineral resource development. It also briefly examines the potential impact of the BBNJ Agreement on EIAs for deep seabed mineral resource development.

-

International Seabed Authority's Efforts to Establish Environmental Thresholds

FUKUSHIMA Tomohiko (Deputy Director General, Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security, Project Professor at the Kobe Ocean-Bottom Exploration Center, Kobe University, Member of the Legal and Technical Comission, International Seabed Authority)

Concerns about the environmental impact of seabed mineral resource development have led to negative feedback from global companies, scientists and policy experts, insurance companies, and some countries. Meanwhile, the International Seabed Authority is working to achieve harmony between development and the environmental conservation through various initiatives, one of which is the establishment of environmental thresholds. Environmental thresholds are expected to be effective, concrete, and transparent, but developing appropriate thresholds is not easy. Therefore, the members of Legal and Technical Comission are currently concentrating their efforts to come up with solutions.

-

Pioneering Japan’s Drive for Rare Earth Security

ISHII Shoichi (Program Director, SIP Phase 3 "National Platform for Innovative Ocean Developments")

SIP Phase 3 "National Platform for Innovative Ocean Developments," a program led by the Cabinet Office promotes the conservation and utilization of oceans, which are crucial to Japan's security as a maritime nation. In addition to implementing research and development results in society, the project aims to collect various ocean data and build a platform to promote resource conservation and climate change response. This article provides an overview of the project's efforts in its third year.

-

The Goals of the Deep-Sea Drilling Vessel Chikyu

EGUCHI Nobuhisa (Counselor for IODP3 of the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology)

The Deep-Sea Drilling Vessel Chikyu is a large-scale research vessel that drills deep beneath the seafloor for the purpose of studying Earth and Life sciences. It has contributed to the International Ocean Drilling Program, which has been running for over 50 years, and has achieved significant results. In addition to scientific drilling, Chikyu has also contributed to resource exploration by developing rare earth extraction technology.

International Seabed Authority's Efforts to Establish Environmental Thresholds

KEYWORDS

Seabed mineral resource development / Marine environmental protection and conservation / Turbidity/resedimentation amount

FUKUSHIMA Tomohiko (Deputy Director General, Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security, Project Professor at the Kobe Ocean-Bottom Exploration Center, Kobe University, Member of the Legal and Technical Comission, International Seabed Authority)

Concerns about the environmental impact of seabed mineral resource development have led to negative feedback from global companies, scientists and policy experts, insurance companies, and some countries. Meanwhile, the International Seabed Authority is working to achieve harmony between development and environmental conservation through various initiatives, one of which is the establishment of environmental thresholds. Environmental thresholds are expected to be effective, concrete, and transparent, but developing appropriate thresholds is not easy. Therefore, the members of the Legal and Technical Commission are currently concentrating their efforts to come up with solutions.

Increasingly sought-after seafloor mineral resources

On April 24, 2025, the White House announced that President Trump had signed an Executive Order promoting the acceleration of seabed mineral development*1 both within and beyond national jurisdiction. Without going into details here, the content*3 appeared to disregard the existence of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which has managed deep seabed*2 mineral resources and related activities under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The ISA Secretary-General immediately expressed that it was regrettable. In addition to reactions from media outlets such as the Financial Times and Wall Street Journal, France, China, and others also criticized the United States for disregarding international norms.

While seabed mineral resource development has suddenly become a topic of much discussion, the above is merely one factor. With nearing the completion of the exploitation regulations that the ISA has been working on, international interest regarding the environment and development has reached unprecedented levels. For example, in 2021, many global companies such as Google and BMW responded to a call from the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and declared they would not use mineral resources from the deep sea due to environmental impact concerns. In 2022, 944 marine scientists and experts from 70 countries made a statement calling for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, and in 2024, major international insurance companies announced the exclusion of deep-sea mining from insurance coverage due to environmental risks. In 2025, the number of countries calling for a moratorium on deep-sea mining reached 37*4. In response to this growing voice for environmental protection, the ISA has not been sitting idle either. It has made repeated efforts to harmonize development and environmental conservation through various initiatives. One of these is the establishment of environmental threshold values.

While seabed mineral resource development has suddenly become a topic of much discussion, the above is merely one factor. With nearing the completion of the exploitation regulations that the ISA has been working on, international interest regarding the environment and development has reached unprecedented levels. For example, in 2021, many global companies such as Google and BMW responded to a call from the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and declared they would not use mineral resources from the deep sea due to environmental impact concerns. In 2022, 944 marine scientists and experts from 70 countries made a statement calling for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, and in 2024, major international insurance companies announced the exclusion of deep-sea mining from insurance coverage due to environmental risks. In 2025, the number of countries calling for a moratorium on deep-sea mining reached 37*4. In response to this growing voice for environmental protection, the ISA has not been sitting idle either. It has made repeated efforts to harmonize development and environmental conservation through various initiatives. One of these is the establishment of environmental threshold values.

IEG members for the three categories (Source: ISA Press Release, 28 June 2024)

Background of the formulation of environmental threshold values

The beginning of this matter dates back to the 2022 ISA Council. The German delegation proposed the establishment of legally binding quantitative environmental thresholds to ensure the effective protection of the marine environment as required by Article 145 of UNCLOS. According to this proposal, environmental thresholds are reference values indicating the maximum level of acceptable impact during seabed mineral resource development and are essential elements for appropriate environmental management. Simply put, environmental thresholds determine the acceptable range of environmental impact. If these values are legally binding, more effective environmental management will become possible. Moreover, if they are quantitative numerical values, conservation goals for developers become more concrete, and this also leads to the transparent evaluation process that those concerned about the environment seek. As a result, many Council members expressed support, hoping to alleviate the anxiety about deep-sea mining that is building in society. The Council immediately resolved to examine thresholds for three categories (toxic substances, turbidity/re-sedimentation, and underwater noise*5 and light pollution) and decided to entrust the specialized examination to the Legal and Technical Commission (LTC). The LTC then decided on two co-chairs for each category, recruited external experts, and formed an Intersessional Expert Group (IEG) to proceed with the work (photo). The next section is an introduction to the efforts of the IEG on turbidity and resedimentation.

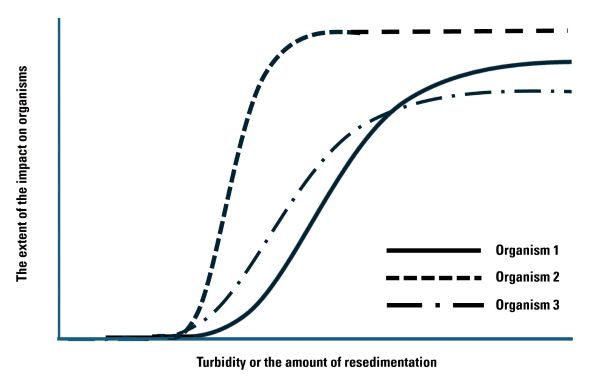

■Figure 1 Dose-response curve

A conceptual diagram showing the relationship between influencing factors (in this case, turbidity or the amount of resedimentation) and the degree of impact on organisms. It illustrates that dose-response curves vary depending on the organisms.

Environmental Thresholds for Turbidity and Resedimentation

Dr. M. Clark of New Zealand and the author have taken on the role of co-chairs for the Intersessional Expert Group (IEG) on turbidity and resedimentation. The IEG focuses on the “turbidity” of seawater and the “settling” of sediments on the seabed caused by mining operations. To date, we have held nine meetings, beginning with a review of prior research. We have engaged in extensive discussions on topics such as standardizing measurement units, defining the scope of affected ecosystems, identifying indicator species, assessing data availability, and understanding the range of variability under natural conditions. However, it appears that more time will be needed before the work is complete. One reason is that it is not easy to evaluate complex deep-sea ecosystems using simple numerical values.

The deep-sea environment is not uniform. Both the ecosystems and the organisms that inhabit them are highly diverse. As a result, the extent of impact, its intensity, and the time required for recovery vary widely. For example, even with the same level of turbidity and resedimentation, the degree of impact differs depending on the size of the organisms. The same applies to differences in ecological characteristics among species. Moreover, the relationship between turbidity/resedimentation amount and the magnitude of impact is not always proportional. Small amounts may have little to no impact, while conversely, once a certain level is exceeded, the impact plateaus (see Figure 1). When asked where that inflection point lies, the answer is that it varies by species.

The experts convened for the IEG possess extensive knowledge, experience, and deep insight, which is immensely reassuring. However, precisely because they are well-versed in the complexity of ecosystems, the more earnestly they engage, the further the goal of establishing environmental thresholds slips away. Yet, if we were to rush to a conclusion at the expense of scientific rigor, it would mean asking these experts to abandon their professionalism. That would defeat the very purpose of the IEG. This is the dilemma shared by both the ISA Secretariat and the co-chairs. Earlier, I mentioned that the initiative to establish environmental thresholds has been positively received by many member states, but the only ones who may be feeling perplexed are the ISA Secretariat and the members of the LTC and IEG, who have been entrusted with the task of creating these thresholds.

The deep-sea environment is not uniform. Both the ecosystems and the organisms that inhabit them are highly diverse. As a result, the extent of impact, its intensity, and the time required for recovery vary widely. For example, even with the same level of turbidity and resedimentation, the degree of impact differs depending on the size of the organisms. The same applies to differences in ecological characteristics among species. Moreover, the relationship between turbidity/resedimentation amount and the magnitude of impact is not always proportional. Small amounts may have little to no impact, while conversely, once a certain level is exceeded, the impact plateaus (see Figure 1). When asked where that inflection point lies, the answer is that it varies by species.

The experts convened for the IEG possess extensive knowledge, experience, and deep insight, which is immensely reassuring. However, precisely because they are well-versed in the complexity of ecosystems, the more earnestly they engage, the further the goal of establishing environmental thresholds slips away. Yet, if we were to rush to a conclusion at the expense of scientific rigor, it would mean asking these experts to abandon their professionalism. That would defeat the very purpose of the IEG. This is the dilemma shared by both the ISA Secretariat and the co-chairs. Earlier, I mentioned that the initiative to establish environmental thresholds has been positively received by many member states, but the only ones who may be feeling perplexed are the ISA Secretariat and the members of the LTC and IEG, who have been entrusted with the task of creating these thresholds.

The future of environmental thresholds

Despite the challenges, tireless efforts continue toward the establishment of environmental thresholds. These efforts are not driven solely by the Council’s resolution, but also by the shared conviction among IEG members that appropriate environmental conservation tools are essential. However, it would be premature to assume that simply adhering to environmental thresholds will ensure harmony between environmental conservation and development. Environmental thresholds are not a panacea. If we aim for better environmental conservation, and if the environmental thresholds we developed are to be used meaningfully, we must be careful to ensure that these values do not take on a life of their own, are not misused, or used as a kind of excuse. Together with Dr. M. Clark, the author plans to work in collaboration with the ISA Secretariat and IEG members to propose ideas that address not only the utility of environmental thresholds but also their limitations. The LTC and IEG pride themselves on being able to face the complexity of ecosystems.

*1 This paper has frequently covered the topic of deep-sea mineral resource development. For example, No.150, No.166, No.274, No.346, No.407, No.509

*2 In this context, the term “deep seabed” refers to “the seabed and ocean floor and subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction” (UNCLOS Article 1, Paragraph 1). For a detailed explanation, see Okamoto Nobuyuki’s article, International Seabed Authority: Past Progress and Future Prospects, published in Issue No. 565 of this paper (February 20, 2024).

https://www.spf.org/opri/en/newsletter/565_1.html

*3 The United States has not ratified UNCLOS and is also not a member state of the ISA.

*4 In June 2025, Luxembourg, Slovenia, Cyprus, Latvia, and the Marshall Islands successively called for a moratorium, bringing the total number of countries to 37.

*5 The issue of ocean noise is explained in detail in Akamatsu Tomonari’s article, The Ocean Noise Problem, published in Issue No. 472 of this paper (April 5, 2020). https://www.spf.org/opri/en/newsletter/472_1.html

*2 In this context, the term “deep seabed” refers to “the seabed and ocean floor and subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction” (UNCLOS Article 1, Paragraph 1). For a detailed explanation, see Okamoto Nobuyuki’s article, International Seabed Authority: Past Progress and Future Prospects, published in Issue No. 565 of this paper (February 20, 2024).

https://www.spf.org/opri/en/newsletter/565_1.html

*3 The United States has not ratified UNCLOS and is also not a member state of the ISA.

*4 In June 2025, Luxembourg, Slovenia, Cyprus, Latvia, and the Marshall Islands successively called for a moratorium, bringing the total number of countries to 37.

*5 The issue of ocean noise is explained in detail in Akamatsu Tomonari’s article, The Ocean Noise Problem, published in Issue No. 472 of this paper (April 5, 2020). https://www.spf.org/opri/en/newsletter/472_1.html