Ocean Newsletter

No.590 March 5, 2025

-

Development of Fish Stock Management at the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC)

HIRUMA Shinji (Assistant Director, International Affairs Division, Fisheries Agency (Planning Team))

The Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) is a regional fisheries management organization that manages tuna stocks, with 26 countries and regions, including Japan, as members. Pacific bluefin tuna stock, which at one time had declined to historic lows, have shown a steady recovery as a result of resource management through the adoption of conservation and management measures by the WCPFC, and WCPFC officially adopted an catch limit increase by 1.1 times for small fish and 1.5 times for large fish at its annual meeting that were held from the end of November 2024.

-

Sustainable Fisheries: From the Perspectives of "Catching" and "Eating"

WADA Tokio (Executive Director, Japan Fisheries Science & Technology Association)

While the state of fishery resources around Japan appears to be relatively stable, the decline in fishery production continues. To achieve a sustainable fishery industry and build a resilient fishery supply and demand system, in addition to maintaining resources "while catching" based on the maximum sustainable yield, it is essential to maintain a production system "while eating" through conscious efforts to produce locally for local consumption, taking into account the characteristics of Japan's fisheries, which are a high-variety, low-volume production.

-

MSC Certification and Skipjack and Tuna Fisheries

ISHII Kozo (Program Director, MSC Japan)

The number of tuna fisheries that have obtained MSC fisheries certification, which is proof of a sustainable fishery, is increasing worldwide, and the background to this is the global expansion of the market for MSC-certified tuna. Obtaining and maintaining MSC fisheries certification also contributes to the development and implementation of appropriate management measures for tuna resources by regional fisheries management organizations, and the choosing of MSC-labeled tuna products by consumers will help preserve tuna resources for the future.

-

IUU Fishing and Japan from the Perspective of Shark Finning

HANAOKA Wakao (CEO, Seafood Legacy Co., Ltd.)

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing is a major threat to the sustainability of seafood resources in the world's oceans. Shark fin is known as a luxury food ingredient around the world, best known for its use in shark fin soup. Unfortunately, a practice known as shark finning, –in which a shark is captured, only its fins are removed and the finless shark is thrown back into the ocean alive–prevails. It is prohibited in many countries and regions due to its cruelty and for the protection of endangered shark species. Shark finning is a typical example of IUU fishing.

Sustainable Fisheries: From the Perspectives of "Catching" and "Eating"

Maintaining Resources "While Catching"

Fishery resources are not only wildlife resources but also valuable food resources for humanity. Therefore, their conservation and management always involve a "catching" perspective. Resources are maintained and renewed through reproduction, in which parents give birth to offspring, but resources through reproduction fluctuate significantly in response to changes in the natural environment. Fishing, conversely, acts to reduce resource volumes. As a result, under fluctuating reproduction relationships, the fundamental principle of fishery resource management is to adjust fishing intensity to leave behind a quantity of parent fish that can produce enough recruitment to achieve Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY).

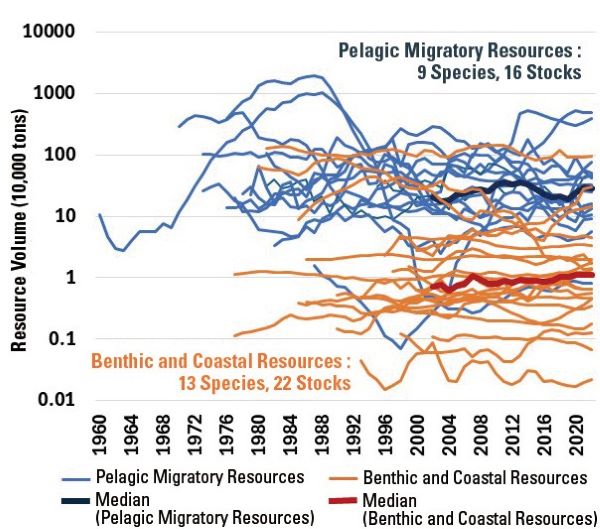

Japan's fishing industry changed to primarily operate in coastal and offshore areas following the ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1996. The 2018 Fisheries Act Reform further strengthened domestic fishery resource management in line with this approach. Figure 1 shows recent trends in resource volumes based on the FY2023 fish stock assessment results (Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency) for 9 species and 16 stocks of pelagic migratory resources such as Japanese sardine, and 13 species and 22 stocks of benthic and coastal resources such as cod and flounder species, for which the amount of parent fish to be secured and the catch limits are set based on MSY criteria. Although there has been an increase and decrease by fish species and stocks, the median values for both resources have remained almost unchanged since 2000. However, not all resources around Japan are included, and some of the resources shown here may require a slight increase in parent stock volumes or catch reduction. Additionally, international resources such as Pacific bluefin tuna and Pacific saury are separately assessed and managed by international organizations. Notably, recent declines have been prominent in Pacific saury and chum salmon stocks. However, the overall fishery resource situation around Japan has been relatively stable in recent years, suggesting that efforts toward resource utilization "while catching" are making progress.

■Figure 1: Trends in Domestic Fishery Resource Volumes in Waters Surrounding Japan (Created by the Author Based on the "FY2023 Fish Stock Assessment Results" (Japan Fisheries Research and

Domestic Production Decline and Consumption Divergence

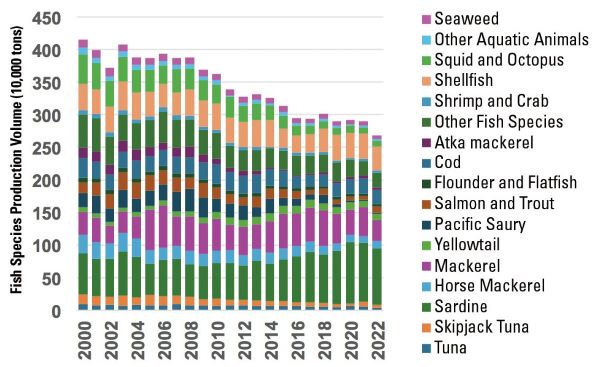

While fishery resources around Japan appear to be relatively stable, fishing production continues to decline. Based on Fisheries and Aquaculture Production Statistics (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries), Figure 2 summarizes fish species production by coastal and offshore fishing from 2000 to 2022, showing a total decrease from 4.15 million tons to 2.69 million tons. While the production volumes of skipjack tuna, tuna, and pelagic fish species such as horse mackerel, mackerel, and sardines have remained fairly unchanged, the production volume of coastal and sedentary species such as seaweed, shrimp and crab, and squid and octopus has declined. The production volume of benthic fish and other fish species has also remained at low levels or declined. In addition, the production volume of salmon and trout, and Pacific saury has also declined sharply.

While past overfishing and recent global warming impacts cannot be denied, the major factor behind this trend is largely considered to be the contraction of the production system itself. This includes the decrease in the number of fishery workers due to Japan's declining birthrate and aging population, and the reduction in the number of fishing vessels accompanying a decrease in production volumes. According to the Fisheries Census conducted every five years by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, from 2003 to 2023 the number of fishing workers has halved from 238,000 to 121,000, and the number of fishing vessels (including non-motorized fishing vessels) has also halved from 214,000 to 109,000. Additionally, changes in dietary habits and price differences with pork and chicken have contributed to consumers moving away from fish, resulting in a decrease in seafood consumption in Japan. Household purchases of fresh seafood have consistently declined, dropping from an annual 44.2 kg in 2000 to just 18.5 kg in 2023, which is less than half (national average for households with two or more people, based on the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications household survey).

■Figure 2: Changes in Fish Species Production Volume by Coastal and Offshore Fishing (Created by the Author Based on the Statistics of Fishery and Fish Culture from the Ministry of Agriculture,

The Necessity of the "Eating" Perspective

In Japan, a variety of fisheries have been developed for the fishery resources unique to each region against the backdrop of the diverse marine environment. Consequently, high-variety, low-volume production has become unavoidable with significant regional and seasonal variations. Therefore, it is difficult to manage the distribution and consumption of these products entirely through supermarkets, which are the center of current fishery product distribution and are based on the four factors of timeliness, quantity, price, and quality in the provision of products. The decline in fisheries production of coastal and sedentary species (Figure 2) can be considered a reflection of these challenges. However, to effectively utilize the fishery resources around Japan and respond to the uncertain future food supply and demand, it is crucial to consciously promote local production for local consumption as well as crops suitable for the land in response to climate change. By stimulating demand through tourism, including inbound tourism, and strengthening direct connections with consumers and actual users within and outside the region through the internet, a cycle between fishery and aquaculture production and fishery product consumption is formed. This approach is expected to lead to the creation of a resilient supply and demand system for Japan as a whole.

Population decline, alongside global warming, is a critical challenge for Japan's future society. Many existing social systems, including railway services, operate on the premise of a certain population or population density. Against this backdrop, population decline and depopulation in rural areas are serious issues and have exposed the vulnerability of logistics infrastructure that has become apparent through recent natural disasters. The securing of burden sharers and the formation and maintenance of a domestic market depend on population size. When creating a cycle of production and consumption in a region through local production for local consumption, it will be necessary to set a range that has a population large enough to be economically self-sustaining, which will likely transcend the boundaries of existing local governments. On this basis, we hope to see initiatives that encourage people to remain in their regions and support the fishing industry “while eating,” through the optimal positioning of production, processing, and distribution hubs, social infrastructure, collaboration with related local industries, cultural and educational enrichment, and the improvement of gender balance.