Ocean Newsletter

No.589 February 20, 2025

-

18 Years as a Judge of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea

YANAI Shunji (Former Judge of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea)

The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea was established by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and is composed of 21 judges. The first Japanese judge, Professor Yamamoto Soji, served one term of nine years, after which the author served two terms of 18 years. The majority of judges strive to find the best solution for the cases that are referred to them, so the direction of the judgment is determined through repeated discussions among the judges. The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea has been highly regarded around the world in the 30 years since its establishment, has begun to accept large cases such as boundary delimitation cases, and its precedents are contributing to the development of the Law of the Sea.

-

Advisory Opinion on Climate Change at the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea

YAMASHITA Tsuyoshi (Research Fellow, Center for International Law and Policy, Tohoku University)

The advisory opinion of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) determined that the parties to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) have an obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment from pollution as a deleterious effects of climate change caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. Many states and international organizations actively exchanged opinions on marine environmental issues related to climate change, and the issues were organized to promote further negotiations in the future. The important significance of ITLOS as a dispute settlement system can be seen in the organization and promotion of such negotiations.

-

Reflection from INC 5- Legally Binding Instrument for Eliminating Plastic Pollution

Emadul ISLAM (Senior Research Fellow, Ocean Policy Research Institute, Sasakawa Peace Foundation)

The article highlights global efforts to tackle plastic pollution through the development of a legally binding international treaty, mandated by the UNEA 5/14 resolution in 2022. The recent INC-5 negotiations in Busan faced challenges, including disagreements on key articles and resistance from petroleum-producing nations. However, over 100 countries supported ambitious goals, such as limiting plastic polymers. Despite delays, progress continues, with strong civil society backing and plans for further negotiations in 2025 to finalize a comprehensive treaty.

-

Ensuring Ocean Equity

Stephanie JUWANA (Co-founder and Program Director at Indonesia Ocean Justice Initiative)

In the midst of a global economy facing many challenges, the ocean is increasingly viewed as a promising economic frontier, and investments in the blue economy have surged. However, if the blue economy is promoted without integrating equity, it could result in widespread injustice. Ensuring ocean equity is essential in promoting durable economic growth, enhancing social stability, and unlocking the full potential of the ocean as a sustainable resource.

Reflection from INC 5- Legally Binding Instrument for Eliminating Plastic Pollution

KEYWORDS

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) / Plastic Treaty / Treaty Negotiations

Emadul ISLAM (Senior Research Fellow, Ocean Policy Research Institute, Sasakawa Peace Foundation)

The article highlights global efforts to tackle plastic pollution through the development of a legally binding international treaty, mandated by the UNEA 5/14 resolution in 2022. The recent INC-5 negotiations in Busan faced challenges, including disagreements on key articles and resistance from petroleum-producing nations. However, over 100 countries supported ambitious goals, such as limiting plastic polymers. Despite delays, progress continues, with strong civil society backing and plans for further negotiations in 2025 to finalize a comprehensive treaty.

Establishing an International Legal Framework to Combat Plastic Pollution

Plastic pollution has emerged as a pervasive global concern, as result to control and eliminate plastic pollution both in the marine and land-based sources legally binding international instruments are crucial. The historical decision was made on March 2, 2022 when a total of 175 countries adopted the United Nations Environmental Assembly (UNEA) 5/14 resolution to develop an international legally binding treaty to eliminate plastic pollution including in the marine environment by 2025. The necessary of plastic treaty is the result of long work of the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP). This article focuses on the background of plastic treaty development and the progress of intergovernmental negotiation committee fifth session (INC-5).

Backdrop of plastic treaty MAPROL to UNEA 5/14 resolution

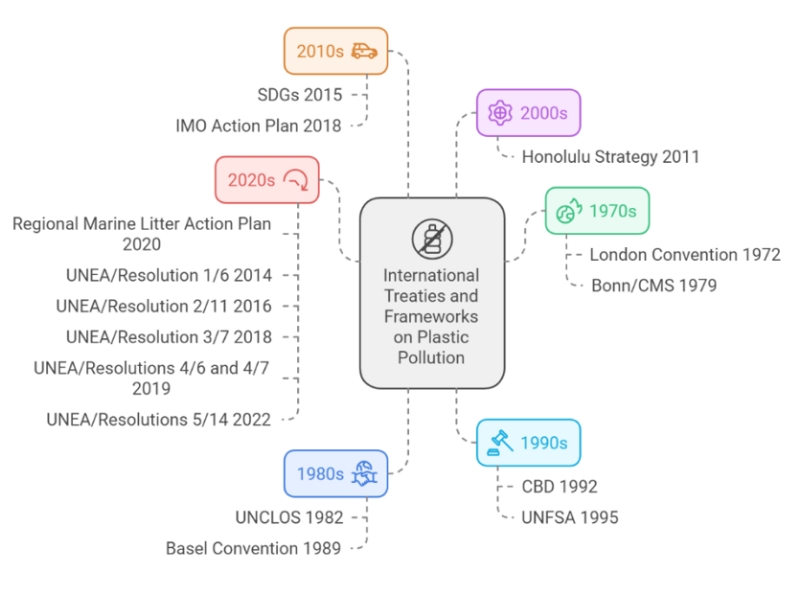

The greatest invention of 19th century was plastic, but this plastic became a major problem because of long period of time taken for degradation, and mismanagement of plastic waste create pollution problem both inland and marine environment and public health. The scientists, policy makers and the non profit activist realized the necessity of eliminate plastic pollution and has been working to develop a policy to end plastic since 1970. Refer to the figure (1) the global legal instruments could be categorized under two regime including policy instruments: those developed before 2000 and those after 2000. Plastic pollution legal instruments inventory study found that before 2000 globally a total of 8 international policies were developed but none of these global policy documents cover land-based source of plastic pollution.

The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) and the London Convention/Protocol are two prominent international agreements that have been established with the objective of effectively mitigating the issue of plastic pollution originating from maritime activities. These binding instruments have been implemented to regulate and control the discharge of plastic waste into the marine environment, thereby addressing the adverse environmental impacts associated with such pollution. The impact of these treaties on regional and national policy responses has been examined, revealing potential limitations in their efficacy in mitigating the issue of land-based sources of plastic pollution. The issue of plastic pollution has been recognized and addressed by the 1989 Basel Convention, which aims to promote environmentally sound waste management practices at the national level.

The United Nations and its associated organization United Nation Environment Program have been playing a vital role to develop or adopt legally binding global policy instruments on plastic pollution. Since 2000, there has been a significant increase in non-binding international policies aimed at addressing land-based plastic pollution. A total of 28 legally binding documents, mostly resolutions from the United Nations Environmental Assembly (UNEA), have been formulated to address plastic pollution from terrestrial sources. Over time, these policies have undergone a gradual transformation, expanding their scope to include more specific classifications, such as “marine plastic litter and microplastic.”

Here is a figure summarizing the international frameworks and treaties relevant to controlling plastic pollution:

The absence of a comprehensive and universally applicable international policy aimed at mitigating the adverse impacts of land-based plastic pollution is a notable concern, as highlighted by the UNEP. During the fifth meeting of UNEA March 2022 adopted a resolution, which mandated the creation of an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) to develop a legally binding instruments to end plastic pollution.

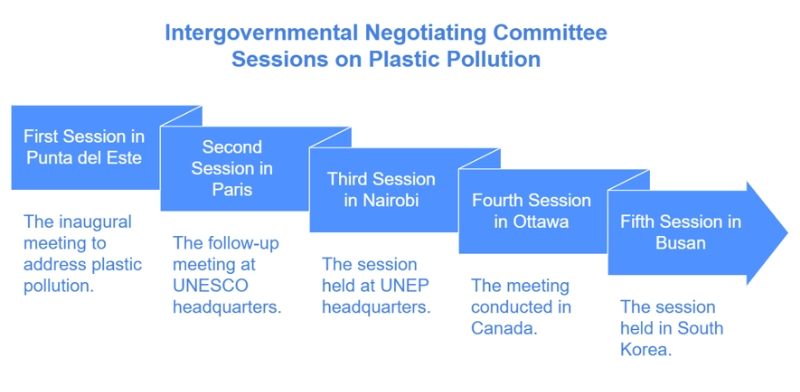

The INC has been organizing the consultation and negotiators meeting are set to meet five times between 2022 and 2024 to work out the details of the legal instrument. However, this resolution 5/14 is highlighting various concept including life cycle of plastic pollution; virgin plastic and recycle plastic, and legacy plastic.

The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) and the London Convention/Protocol are two prominent international agreements that have been established with the objective of effectively mitigating the issue of plastic pollution originating from maritime activities. These binding instruments have been implemented to regulate and control the discharge of plastic waste into the marine environment, thereby addressing the adverse environmental impacts associated with such pollution. The impact of these treaties on regional and national policy responses has been examined, revealing potential limitations in their efficacy in mitigating the issue of land-based sources of plastic pollution. The issue of plastic pollution has been recognized and addressed by the 1989 Basel Convention, which aims to promote environmentally sound waste management practices at the national level.

The United Nations and its associated organization United Nation Environment Program have been playing a vital role to develop or adopt legally binding global policy instruments on plastic pollution. Since 2000, there has been a significant increase in non-binding international policies aimed at addressing land-based plastic pollution. A total of 28 legally binding documents, mostly resolutions from the United Nations Environmental Assembly (UNEA), have been formulated to address plastic pollution from terrestrial sources. Over time, these policies have undergone a gradual transformation, expanding their scope to include more specific classifications, such as “marine plastic litter and microplastic.”

Here is a figure summarizing the international frameworks and treaties relevant to controlling plastic pollution:

The absence of a comprehensive and universally applicable international policy aimed at mitigating the adverse impacts of land-based plastic pollution is a notable concern, as highlighted by the UNEP. During the fifth meeting of UNEA March 2022 adopted a resolution, which mandated the creation of an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) to develop a legally binding instruments to end plastic pollution.

The INC has been organizing the consultation and negotiators meeting are set to meet five times between 2022 and 2024 to work out the details of the legal instrument. However, this resolution 5/14 is highlighting various concept including life cycle of plastic pollution; virgin plastic and recycle plastic, and legacy plastic.

Figure 1 Treaty and framework include plastic pollution

Figure 2 INC host places

Reflection of INC-5 and progress of plastic treaty

The fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee was officially inaugurated by its Chair, Luis Vayas Valdivieso, at 10:15 a.m. on Monday, November 25, 2024, at BEXCO in Busan, Republic of Korea. In the opening remarks chair of INC-5 said that in his words-

“Plastic pollution constituted an urgent and insidious threat to ecosystems, economies and human health. The magnitude of the crisis was evident; without significant intervention, the amount of plastic entering the environment annually by 2040 was expected to nearly double compared to 2022” (Valdivieso-INC-5; November 25, 2024)

November 25, 2024, marked 1,000 days since the adoption of the landmark United Nations Environment Assembly resolution 5/14, which initiated the mandate for the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee's negotiations.

The INC-5 chair formed four contact group and a legal drafting group to start negotiation on the Non paper 3 document. This Non paper-3 document was considered to basis of INC-5 negotiations and the total 32 article of Non paper 3 document distributed among the four contact group for negotiations.

Following four days of negotiations on the Non-Paper 3 document by the relevant parties, the Chair of INC-5 announced the release of the Chair’s Text on December 1, 2024. This text was formulated based on the outcomes of informal consultations held on November 30, along with input from the Co-Chairs of the four Contact Groups and the facilitators of the informal discussions.

The Chair Text is an expanded and revised version of Non-Paper 3. However, after six days of negotiations among the various parties, consensus could not be reached on several key articles, including Article 3 (Plastic Products and Chemicals), Article 6 (Sustainable Production), Article 8 (Plastic Waste Management), Article 10 (Just Transition), Article 11 (Financial Mechanism), and Article 12 (Capacity Development). This lack of agreement was particularly evident among petroleum-producing countries such as Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United States.

Furthermore, Non-Paper 3 was criticized at the outset of the INC-5 negotiations for omitting the scope and objectives of the treaty—an issue that remains unaddressed in the Chair Text.

Despite being targeted as the final negotiation session, INC-5 failed to achieve consensus on critical articles. The lack of agreement stemmed from a small minority of countries prioritizing national interests over the urgency of addressing plastic pollution, despite overwhelming scientific evidence underscoring the need for this treaty.

Nevertheless, INC-5 marked a significant milestone in the progress toward developing a universal treaty. The negotiation text has been streamlined, with some draft provisions now free of brackets. However, the Like-Minded Countries (LMC), a group focused solely on waste management and recycling, requested the entire draft text to remain bracketed, emphasizing the principle that "nothing is agreed until everything is agreed."

On the other hand, the High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution (HAC) gained momentum, with growing support for an ambitious treaty. Over 100 countries endorsed the inclusion of Article 6 on [supply] [sustainable production] and the establishment of global targets to reduce primary plastic production. Additionally, 94 countries supported the inclusion of Article 3 on [plastic products].

During the final plenary, Juliet Kabera of Rwanda, representing HAC and 85 countries, delivered a powerful statement calling for high ambition. Her plea was met with a standing ovation from the majority of the plenary, signifying strong support for an ambitious treaty. These member states must now prepare thoroughly for future negotiation rounds and the intersessional work ahead. While the treaty is not yet finalized, substantial progress has been achieved, with ambitious nations finding common ground to advocate with a unified voice.

The final plenary on December 1, 2024, echoed powerful messages from delegates, amplifying collective ambition:

“Plastic pollution constituted an urgent and insidious threat to ecosystems, economies and human health. The magnitude of the crisis was evident; without significant intervention, the amount of plastic entering the environment annually by 2040 was expected to nearly double compared to 2022” (Valdivieso-INC-5; November 25, 2024)

November 25, 2024, marked 1,000 days since the adoption of the landmark United Nations Environment Assembly resolution 5/14, which initiated the mandate for the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee's negotiations.

The INC-5 chair formed four contact group and a legal drafting group to start negotiation on the Non paper 3 document. This Non paper-3 document was considered to basis of INC-5 negotiations and the total 32 article of Non paper 3 document distributed among the four contact group for negotiations.

Following four days of negotiations on the Non-Paper 3 document by the relevant parties, the Chair of INC-5 announced the release of the Chair’s Text on December 1, 2024. This text was formulated based on the outcomes of informal consultations held on November 30, along with input from the Co-Chairs of the four Contact Groups and the facilitators of the informal discussions.

The Chair Text is an expanded and revised version of Non-Paper 3. However, after six days of negotiations among the various parties, consensus could not be reached on several key articles, including Article 3 (Plastic Products and Chemicals), Article 6 (Sustainable Production), Article 8 (Plastic Waste Management), Article 10 (Just Transition), Article 11 (Financial Mechanism), and Article 12 (Capacity Development). This lack of agreement was particularly evident among petroleum-producing countries such as Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United States.

Furthermore, Non-Paper 3 was criticized at the outset of the INC-5 negotiations for omitting the scope and objectives of the treaty—an issue that remains unaddressed in the Chair Text.

Despite being targeted as the final negotiation session, INC-5 failed to achieve consensus on critical articles. The lack of agreement stemmed from a small minority of countries prioritizing national interests over the urgency of addressing plastic pollution, despite overwhelming scientific evidence underscoring the need for this treaty.

Nevertheless, INC-5 marked a significant milestone in the progress toward developing a universal treaty. The negotiation text has been streamlined, with some draft provisions now free of brackets. However, the Like-Minded Countries (LMC), a group focused solely on waste management and recycling, requested the entire draft text to remain bracketed, emphasizing the principle that "nothing is agreed until everything is agreed."

On the other hand, the High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution (HAC) gained momentum, with growing support for an ambitious treaty. Over 100 countries endorsed the inclusion of Article 6 on [supply] [sustainable production] and the establishment of global targets to reduce primary plastic production. Additionally, 94 countries supported the inclusion of Article 3 on [plastic products].

During the final plenary, Juliet Kabera of Rwanda, representing HAC and 85 countries, delivered a powerful statement calling for high ambition. Her plea was met with a standing ovation from the majority of the plenary, signifying strong support for an ambitious treaty. These member states must now prepare thoroughly for future negotiation rounds and the intersessional work ahead. While the treaty is not yet finalized, substantial progress has been achieved, with ambitious nations finding common ground to advocate with a unified voice.

The final plenary on December 1, 2024, echoed powerful messages from delegates, amplifying collective ambition:

- Mexico: "We carry the weight of expectation from citizens counting on us to protect them and the environment from plastic pollution. Let us seize the moment to deliver decisive action that our people and planet urgently need."

- Fiji: "We believe in multilateralism... We can develop a treaty that becomes a lasting legacy, demonstrating our resilience and commitment to our planet and future generations."

- Panama: "To the activists and civil society who have carried this fight, you are the heartbeat of this movement. Rest, recharge, and return stronger... We might have been delayed, but we have not been stopped."

- Republic of Korea: "Let history remember us as leaders who rose above differences, chose cooperation over conflict, and acted decisively when the stakes were at their highest."

Future Outlook

INC-5 success was delayed due to the lack of agreement among countries, as the consensus-based rules allowed a few "like-minded" nations, such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Russia, to block progress. However, this session marked a significant milestone, with over 100 countries uniting to advocate for the inclusion of plastic polymer caps as a critical component of an effective agreement to tackle plastic pollution. These nations sent a clear and decisive message: "No treaty is better than a weak one."

The unwavering support from civil society fueled this determination, empowering countries to remain steadfast in their commitment. While the realization of this vision will take longer, with negotiations resuming in 2025 at a yet-to-be-determined time and location for INC-5.2, the delay is seen as an opportunity. Holding out for an ambitious and comprehensive treaty will make the eventual victory even more meaningful and significant.

The unwavering support from civil society fueled this determination, empowering countries to remain steadfast in their commitment. While the realization of this vision will take longer, with negotiations resuming in 2025 at a yet-to-be-determined time and location for INC-5.2, the delay is seen as an opportunity. Holding out for an ambitious and comprehensive treaty will make the eventual victory even more meaningful and significant.