Ocean Newsletter

No.552 August 5, 2023

-

20 Years Since Enactment of the Law for the Promotion of Nature Restoration

WATANABE Tsunao (Senior Programme Manager, UNU Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability / Senior Research Fellow, Japan Wildlife Research Center)

Twenty years have passed since the enactment of the Law for the Promotion of Nature Restoration on January 1, 2003. Along with presenting the achievements and challenges of this twenty years, I would like to introduce the new global goals regarding biodiversity and consider the new developments in nature restoration as they have been affected by international discussions and policy trends, including the adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, etc.

-

Crucial Perspectives on the Deployment of Offshore Wind Power Generation

HASE Shigeto (Director of Tokyo Fisheries Promotion Foundation, Representative / Chairman of Marine Fisheries Technology Council / Former Director-General, Fisheries Agency of Japan)

For offshore fishermen, conventional approaches to fisheries promotion accompanying development of offshore wind power generation facilities, such as the artificial reef effect of offshore windmill facilities and job creation for coastal communities caused by maintenance and inspection, are not appealing. Additionally, these fishermen are often impacted by multiple wind power installations at once due to the vast areas they cover for their fishing operations. As the government lays out its blueprint for the advent of floating offshore wind power, it bears the responsibility to assiduously identify "zones where fishing will remain unaffected." This responsibility is mandated by the Act on Promoting the Utilization of Sea Areas for the Development of Marine Renewable Energy Power Generation Facilities. In conjunction, the government has a duty to disclose plans for all relevant projects to these fishermen.

-

Embarking on ‘Umigyou’ through Fixed Net Fishing

SOHTOME Keiichi (President, Gate Inc.)

When something mingles with something else, innovation occurs. When you mix something with something else, you can’t be sure what will happen, but something will happen. We are happily imagining the future of fishing villages through our umigyou activities, as we bring together fishing and Japanese pubs, the sea and education, fishing villages and women, and adults and children.

Crucial Perspectives on the Deployment of Offshore Wind Power Generation

KEYWORDS

Floating Offshore Wind Power / Fisheries Industry / Fisheries Cooperation

HASE Shigeto (Director of Tokyo Fisheries Promotion Foundation, Representative / Chairman of Marine Fisheries Technology Council / Former Director-General, Fisheries Agency of Japan)

For offshore fishermen, conventional approaches to fisheries promotion accompanying development of offshore wind power generation facilities, such as the artificial reef effect of offshore windmill facilities and job creation for coastal communities caused by maintenance and inspection, are not appealing. Additionally, these fishermen are often impacted by multiple wind power installations at once due to the vast areas they cover for their fishing operations. As the government lays out its blueprint for the advent of floating offshore wind power, it bears the responsibility to assiduously identify "zones where fishing will remain unaffected." This responsibility is mandated by the Act on Promoting the Utilization of Sea Areas for the Development of Marine Renewable Energy Power Generation Facilities. In conjunction, the government has a duty to disclose plans for all relevant projects to these fishermen.

The Current State of Offshore Wind Power Projects

The 6th Strategic Energy Plan, established in October 2021, set a goal of forming 10 GW projects by 2030. In line with the target, looking only at projects in general sea areas based on the Act on Promoting the Utilization of Sea Areas for the Development of Marine Renewable Energy Power Generation Facilities, approximately 3.5 GW of projects have been put together in Akita, Niigata, Chiba, and Nagasaki Prefectures.1 Having insight into the origin of this law, which was enacted after an agreement was reached based on the fisheries cooperative’s approach of forming projects in waters without disrupting the fishing industry, I can attest to the extensive efforts required to reach this milestone.

Meanwhile, the process of establishing projects in each water area has faced several challenges. These challenges include confusion on shore caused by multiple power generation companies independently entering the area to initiate projects, inadequate inter-departmental communication at the prefectural level, and a limited awareness of the actual operation. In addition, there has been insufficient engagement with local fishermen who operate outside the jurisdictional area of their respective local governments.

From the viewpoint of the companies from the power generation sector, after many visits led them to believe they had reached an understanding with local fisheries cooperatives, they were unexpectedly met with opposition from the offshore fishermen who actually operate in these areas. Conversely, these offshore fishermen felt blindsided as projects were being initiated in their fishing territories without their prior knowledge. As highlighted in a June 2022 report “Yojo furyoku hatsuden shisetsu no gyogyo eikyo chosa jisshi no tameni (For the Implementation of a Study of the Impact of Offshore Wind Power Generation Facilities on Fisheries)”2 by the Marine Fisheries Technology Council where the author serves as its representative, the first step in evaluating the impact on fisheries is to "identify the affected fishermen."

Meanwhile, the process of establishing projects in each water area has faced several challenges. These challenges include confusion on shore caused by multiple power generation companies independently entering the area to initiate projects, inadequate inter-departmental communication at the prefectural level, and a limited awareness of the actual operation. In addition, there has been insufficient engagement with local fishermen who operate outside the jurisdictional area of their respective local governments.

From the viewpoint of the companies from the power generation sector, after many visits led them to believe they had reached an understanding with local fisheries cooperatives, they were unexpectedly met with opposition from the offshore fishermen who actually operate in these areas. Conversely, these offshore fishermen felt blindsided as projects were being initiated in their fishing territories without their prior knowledge. As highlighted in a June 2022 report “Yojo furyoku hatsuden shisetsu no gyogyo eikyo chosa jisshi no tameni (For the Implementation of a Study of the Impact of Offshore Wind Power Generation Facilities on Fisheries)”2 by the Marine Fisheries Technology Council where the author serves as its representative, the first step in evaluating the impact on fisheries is to "identify the affected fishermen."

The Challenges of Offshore Developments

Recently, the government has been considering legal measures to extend the offshore developments into the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). In April 2023, the third meeting of the Ministerial Council on Renewable Energy, Hydrogen and Related Issues was held at the Prime Minister's Office. At the meeting, Prime Minister Kishida stated that regarding floating offshore wind power generation, the public and private sectors will cooperate to formulate future industrial strategies and implementation goals at an early stage and attract investments from Japan and abroad. In an era where decarbonization is growing increasingly urgent, extending these installations into the EEZ based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, while utilizing floating technology, is a logical step. While coastal fishermen in certain districts have benefited from fishery promotion measures, such as the artificial reef effect by windmills and job creation for maintenance and inspections of facilities, these measures do not seem appealing to offshore fishermen. In particular, for those major offshore fisheries that require large fishing grounds, such as purse seining, bottom trawling, and floating long line, these installations could be more of a hindrance than a help for their operations. Thus, a significant future challenge is to establish how to promote fishery cooperation, which is the fundamental concept of the Act on Promoting the Utilization of Sea Areas for the Development of Marine Renewable Energy Power Generation Facilities, in the waters earmarked for floating offshore wind power generation.

Compared to their entire fishing zone, the size of each project area is not particularly large for offshore fishermen. Nevertheless, it is unreasonable to expect them to assess different companies’ projects individually without a comprehensive plan indicating the scope and number of future projects. It is even more unreasonable in a situation where the government goal is to achieve “10 GW by 2030” followed by “30-45 GW by 2040,” with talk of the need for even further expansion. In May 2023, the Japan Wind Power Association proposed supplying 60 GW of electricity solely from floating offshore wind installations by 2050. If public and private sectors are to coordinate in formulating implementation goals, as Prime Minister Kishida stated, it should not be a “public-private council” without the fisheries industry, but the fisheries industry must be included in the public-private dialogue. Failing to do so, it is highly unlikely that the hoped-for results would be obtained.

Even if the projects do not expand into EEZs, caution is needed in future when seriously considering the expansion of potential waters into offshore areas, mainly for floating installations. Inefficient scenarios that only end up causing unnecessary trouble must be avoided, such as companies directing their project formation efforts to waters that clearly cannot meet the legal requirements— for example, areas where illegal fishing occurs, and conflicts are likely. For such reasons, governmental intervention is necessary to specify which fishing methods and practices cannot coexist physically and spatially with offshore wind power generation installations, and to coordinate in advance their segregation, rather than leaving this to individual companies.

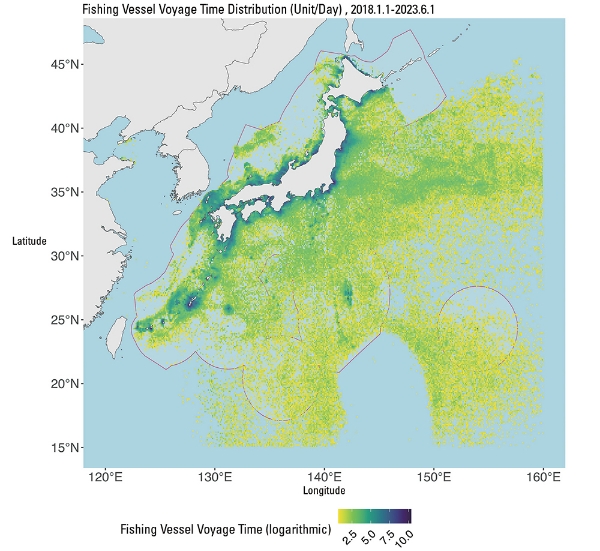

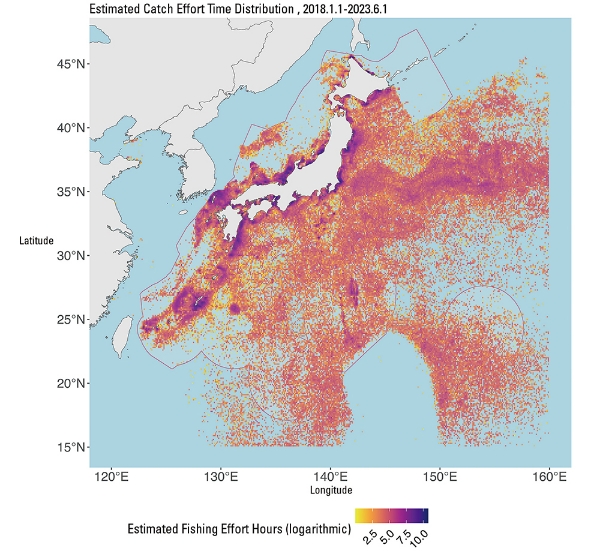

For this purpose, Gakushi Ishimura of Iwate University and Keita Abe of Musashi University provided a visualization of the overall fishing activities in offshore areas based on the AIS(Automatic Identification System) data from fishing vessels (Figures 1 and 2).

These figures are compilations of information on approximately 6,500 individual Japanese fishing vessels that are subject to monitoring, based on data from Global Fishing Watch, the international non-profit organization that is working to eradicate illegal fishing vessels. In context, when compared with the 2021 Fishing Vessel Statistics based on gross tonnage, this data set represents roughly 30% of fishing vessels between 15 and 20 tons, over 70% of those between 20 and 100 tons, and 97% of those over 100 tons. Consequently, it is believed to meaningfully reflect the activity status of Japanese fishing vessels in offshore areas. The voyage time in Figure 1 includes not only the time spent on fishing activities but also the time spent on round trips between fishing grounds and ports and exploration activities. Fishing effort time in Figure 2 is estimated by machine learning fishing behavior analysis. All data are combined here to reveal general trends, but analysis according to fishing method is, of course, also possible.

Beyond the immediate physical and spatial impacts of these operations related to offshore wind power generation on fisheries, there are also impacts on migratory marine species. Additionally, it is also possible that fishing grounds may change due to the ongoing shifts in the marine environment, which is affecting many fish species. Therefore, it is impossible to assure that there will be no hindrance in blank water areas where fishing boats have not sailed in the past. However, we hope that these figures will be used to reduce frustration on the part of both fishermen and power generation business operators, helping to ensure their segregation is constructive and effective. The government must first make maximum efforts to identify "areas where fishing will not be disrupted," as required by law. Concurrently, instead of interfacing with fishermen on an individual project basis, the government should offer a holistic outline of all proposed offshore wind projects and their potential implications for the fishing community. (End)

Compared to their entire fishing zone, the size of each project area is not particularly large for offshore fishermen. Nevertheless, it is unreasonable to expect them to assess different companies’ projects individually without a comprehensive plan indicating the scope and number of future projects. It is even more unreasonable in a situation where the government goal is to achieve “10 GW by 2030” followed by “30-45 GW by 2040,” with talk of the need for even further expansion. In May 2023, the Japan Wind Power Association proposed supplying 60 GW of electricity solely from floating offshore wind installations by 2050. If public and private sectors are to coordinate in formulating implementation goals, as Prime Minister Kishida stated, it should not be a “public-private council” without the fisheries industry, but the fisheries industry must be included in the public-private dialogue. Failing to do so, it is highly unlikely that the hoped-for results would be obtained.

Even if the projects do not expand into EEZs, caution is needed in future when seriously considering the expansion of potential waters into offshore areas, mainly for floating installations. Inefficient scenarios that only end up causing unnecessary trouble must be avoided, such as companies directing their project formation efforts to waters that clearly cannot meet the legal requirements— for example, areas where illegal fishing occurs, and conflicts are likely. For such reasons, governmental intervention is necessary to specify which fishing methods and practices cannot coexist physically and spatially with offshore wind power generation installations, and to coordinate in advance their segregation, rather than leaving this to individual companies.

For this purpose, Gakushi Ishimura of Iwate University and Keita Abe of Musashi University provided a visualization of the overall fishing activities in offshore areas based on the AIS(Automatic Identification System) data from fishing vessels (Figures 1 and 2).

These figures are compilations of information on approximately 6,500 individual Japanese fishing vessels that are subject to monitoring, based on data from Global Fishing Watch, the international non-profit organization that is working to eradicate illegal fishing vessels. In context, when compared with the 2021 Fishing Vessel Statistics based on gross tonnage, this data set represents roughly 30% of fishing vessels between 15 and 20 tons, over 70% of those between 20 and 100 tons, and 97% of those over 100 tons. Consequently, it is believed to meaningfully reflect the activity status of Japanese fishing vessels in offshore areas. The voyage time in Figure 1 includes not only the time spent on fishing activities but also the time spent on round trips between fishing grounds and ports and exploration activities. Fishing effort time in Figure 2 is estimated by machine learning fishing behavior analysis. All data are combined here to reveal general trends, but analysis according to fishing method is, of course, also possible.

Beyond the immediate physical and spatial impacts of these operations related to offshore wind power generation on fisheries, there are also impacts on migratory marine species. Additionally, it is also possible that fishing grounds may change due to the ongoing shifts in the marine environment, which is affecting many fish species. Therefore, it is impossible to assure that there will be no hindrance in blank water areas where fishing boats have not sailed in the past. However, we hope that these figures will be used to reduce frustration on the part of both fishermen and power generation business operators, helping to ensure their segregation is constructive and effective. The government must first make maximum efforts to identify "areas where fishing will not be disrupted," as required by law. Concurrently, instead of interfacing with fishermen on an individual project basis, the government should offer a holistic outline of all proposed offshore wind projects and their potential implications for the fishing community. (End)

■Figure 1: Distribution of cumulative estimated fishing vessel voyage hours per 0.1-degree mesh from January 1, 2018, to June 1, 2023.

■Figure 2: Distribution of cumulative estimated fishing effort hours by 0.1-degree mesh from January 1, 2018, to June 1, 2023.

1. Act on Promoting the Utilization of Sea Areas for the Development of Marine Renewable Energy Power Generation Facilities (2018) Reference: Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, "Offshore Wind Power Related Systems".

https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/category/saving_and_new/saiene/yojo_furyoku/

2. "Marine Fisheries Technology Council” page on the Japan Fisheries Science and Technology Association website: http://www.jfsta.or.jp/activity/kaiyousuisan/

https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/category/saving_and_new/saiene/yojo_furyoku/

2. "Marine Fisheries Technology Council” page on the Japan Fisheries Science and Technology Association website: http://www.jfsta.or.jp/activity/kaiyousuisan/