Ocean Newsletter

No.547 May 20, 2023

-

SynObs: A Synergistic Observing Network for Ocean Prediction

FUJII Yosuke (Department of Atmosphere, Ocean, and Earth System Modeling Research, Meteorological Research Institute, Japan Meteorological Agency / Co-chair of UN Decade of Ocean Science’s SynObs project)

SynObs is one of the Japan-led projects being performed as part of the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science. It aims to propose an efficient ocean observing network that maximizes the synergistic effects of various observational data for predicting the oceans. We expect active participation from Japanese researchers in ocean science.

-

Ocean Discharge of ALPS Treated Water and International Law: The Positioning of Radiological Impact Assessments (RIA)

TORIYABE Jo (Lecturer, Department of Law, Faculty of Law, Setsunan University)

The plan to dispose of the increasing ALPS-treated water from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant through ocean discharge is progressing. In November 2021, following the government's decision on the ocean discharge policy, Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) released a Radiological Impact Assessment (RIA) predicting the environmental and human impacts if the treated water were discharged into the ocean. On the other hand, international law mandates the implementation of an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for activities that may have significant adverse effects on other countries' environments. This paper will examine TEPCO's RIA from the perspective of international law.

-

Taking Pride in the ORAHONO Sea: School for the Ocean and Hope in Sanriku

AOYAMA Jun (Director, Otsuchi Coastal Research Center, The University of Tokyo)

The University of Tokyo’s Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute and the Institute of Social Science teamed up in 2018 to start the School for the Ocean and Hope in Sanriku, a project seeking to provide hope to the region by rebuilding local identity with the ocean as a base. It has been five years since the project began, and as residents gradually come to appreciate its aims there is a feeling that it’s finally starting to bear fruit.

Ocean Discharge of ALPS Treated Water and International Law: The Positioning of Radiological Impact Assessments (RIA)

KEYWORDS

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) / United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea / ALPS Treated Water

TORIYABE Jo (Lecturer, Department of Law, Faculty of Law, Setsunan University)

The plan to dispose of the increasing ALPS-treated water from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant through ocean discharge is progressing. In November 2021, following the government's decision on the ocean discharge policy, Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) released a Radiological Impact Assessment (RIA) predicting the environmental and human impacts if the treated water were discharged into the ocean. On the other hand, international law mandates the implementation of an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for activities that may have significant adverse effects on other countries' environments. This paper will examine TEPCO's RIA from the perspective of international law.

TEPCO's Radiological Impact Assessment (RIA)

Contaminated water at the TEPCO Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (hereinafter “Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant”) continues to increase and is stored in over 1,000 tanks constructed on the plant premises after being treated by the Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS) to remove most radioactive substances. The water treated by ALPS and other methods, which reduces the concentration of radioactive substances other than tritium to safe standards, is called ALPS-treated water (hereinafter “treated water”). It was in April 2021, that the Government of Japan decided on a basic policy of discharging treated water into the ocean. Following this policy, TEPCO conducted a Radiological Impact Assessment (RIA) and published a report in November 2021 (later revised several times).

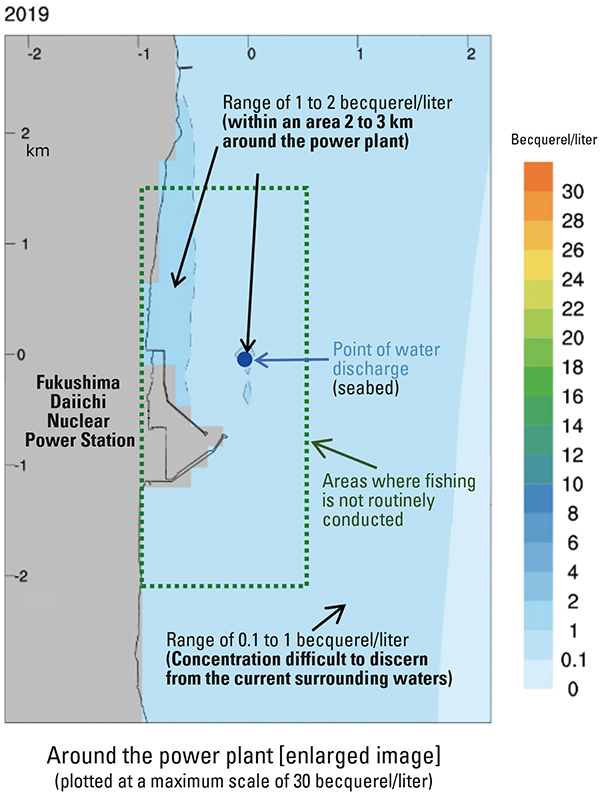

The RIA assessed the diffusion of discharged tritium into the ocean and its impact on humans and marine organisms (flounder, crabs, algae, etc.). Simulation results indicated that the tritium concentration would be higher than the natural concentration in seawater only within a 2-3 km range from the plant (see figure). Furthermore, the impact of discharged radioactive substances on humans and marine organisms was considered "extremely minor," even when considering both external exposure from seawater and beaches and internal exposure from consuming seafood, the results being significantly lower than the annual exposure limit for the general public. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) gave the RIA a generally positive reception.

The RIA assessed the diffusion of discharged tritium into the ocean and its impact on humans and marine organisms (flounder, crabs, algae, etc.). Simulation results indicated that the tritium concentration would be higher than the natural concentration in seawater only within a 2-3 km range from the plant (see figure). Furthermore, the impact of discharged radioactive substances on humans and marine organisms was considered "extremely minor," even when considering both external exposure from seawater and beaches and internal exposure from consuming seafood, the results being significantly lower than the annual exposure limit for the general public. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) gave the RIA a generally positive reception.

The RIA as a Requirement of International Law

In Japan, the Environmental Impact Assessment Act was established in 1997 as a mechanism for project proponents to predict and assess the impact of large-scale development projects on the environment before they are implemented and minimize those impacts as much as possible. However, this law does not cover discharging water into the ocean, as it does not include impacts occurring after project commencement or due to accidents. Therefore, if the RIA is not an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) under this law, on what legal basis was it conducted?

In its basic policy, the government stated that it would "adopt measures to assess the potential impact on the marine environment, taking into account relevant international laws and practices." This clearly suggests that the implementation of the RIA was influenced by international law. If international law requires an EIA before an offshore discharge can be conducted, would this RIA be the equivalent of an EIA under international law? If so, it will be regarded as important under international law whether or not the RIA follows the EIA standards as required by international law.

In its basic policy, the government stated that it would "adopt measures to assess the potential impact on the marine environment, taking into account relevant international laws and practices." This clearly suggests that the implementation of the RIA was influenced by international law. If international law requires an EIA before an offshore discharge can be conducted, would this RIA be the equivalent of an EIA under international law? If so, it will be regarded as important under international law whether or not the RIA follows the EIA standards as required by international law.

Obligation to Implement EIAs Under International Law

International law consists of treaties, which are written agreements between countries, and customary international law, which are legal norms formed through the accumulation of state practices. The latter is binding on all countries. Recent international case law has held that countries planning to perform actions with the potential for significant adverse effects on other countries' environments have an obligation to conduct an EIA (the implementing entity may be the project proponent). The precedents regard such obligations as customary international law and interpret them as consisting of the following three steps (cf. road construction case, decision of the International Court of Justice). In other words, the country planning an action must: (1) ascertain whether the proposed action entails a risk of significant transboundary environmental damage (preliminary assessment); (2) if such a risk exists, it must conduct an EIA (proper EIA); and (3) if the risk of significant transboundary damage is identified through the EIA, it must notify and consult in good faith with the affected country if it is deemed necessary to determine measures to prevent or mitigate such damage (notification and consultation).

In addition to customary international law, Japan must comply with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in the event of an ocean discharge. Article 206 of the Convention, which stipulates the obligation to implement EIAs, can be interpreted under the three steps mentioned above. That is, the country with jurisdiction over the activity must (1) ascertain whether the proposed activity is likely to cause substantial pollution or significant and adverse changes to the marine environment (preliminary assessment); (2) if there are reasonable grounds to believe that it is likely to be the case, it must assess the potential effects of the activity on the marine environment to the extent practicable (i.e., perform a proper EIA); and (3) the results of the assessment must be made public or provided to international organizations (publication and provision).

In addition to customary international law, Japan must comply with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in the event of an ocean discharge. Article 206 of the Convention, which stipulates the obligation to implement EIAs, can be interpreted under the three steps mentioned above. That is, the country with jurisdiction over the activity must (1) ascertain whether the proposed activity is likely to cause substantial pollution or significant and adverse changes to the marine environment (preliminary assessment); (2) if there are reasonable grounds to believe that it is likely to be the case, it must assess the potential effects of the activity on the marine environment to the extent practicable (i.e., perform a proper EIA); and (3) the results of the assessment must be made public or provided to international organizations (publication and provision).

Was the RIA in Line with International Law?

Where does the TEPCO’s RIA fit within the obligations to implement EIAs (steps 1 to 3) required by customary international law and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea? What if the RIA is considered a "proper EIA" (step 2)? Neither customary international law nor the United Nations Convention specifies the content of the EIA to be implemented, leaving it to each country's domestic laws and regulations. If Japan's Environmental Impact Assessment Act does not apply to ocean discharges, international law grants the Japanese government (with TEPCO as the implementing entity) discretion regarding the content of the EIA. At first glance, it might seem harmless to position the RIA as the proper EIA, but this would indicate that our nation accepts the risk of severe transnational damage due to the ocean discharge being performed at the preliminary assessment phase. However, it is somewhat puzzling that the RIA does not examine the potential for transboundary impacts at all. As a matter of fact, the preliminary assessment report for the RIA has not been published, at least not yet.

On the other hand, what happens if the RIA is considered as a "preliminary assessment" (step 1)? In a preliminary assessment, the issue becomes whether the adverse effects on other countries have reached the level of "significant" or "substantial." There is no general standard for this judgment, and it is left to the discretion of the country where the activity occurs, considering the specific circumstances. According to the RIA, the impact is "extremely minor" even within Japan's territorial waters, let alone other countries. Therefore, it is understood that the obligation to conduct an EIA under international law ends at the preliminary assessment stage, and that there is no need to conduct a proper EIA for ocean discharges. This explanation seems more plausible. In any case, given the content of the assessment report, the RIA does not raise significant issues of violation of the EIA implementation obligation under international law regarding the discharge of treated water into the sea.

However, concerns about reputational damage to marine products due to the discharge of treated water remain strong among fisheries, and it is highly desirable that the Japanese government

maintain ongoing dialogues to gain their understanding. At the same time, it is necessary to enhance the transparency of the RIA data through measures such as strengthening monitoring systems before and after discharges and providing as many opportunities for explanation as possible to neighboring countries such as China, South Korea, and Pacific Island nations that call for the suspension or postponement of the discharge of treated water. (End)

On the other hand, what happens if the RIA is considered as a "preliminary assessment" (step 1)? In a preliminary assessment, the issue becomes whether the adverse effects on other countries have reached the level of "significant" or "substantial." There is no general standard for this judgment, and it is left to the discretion of the country where the activity occurs, considering the specific circumstances. According to the RIA, the impact is "extremely minor" even within Japan's territorial waters, let alone other countries. Therefore, it is understood that the obligation to conduct an EIA under international law ends at the preliminary assessment stage, and that there is no need to conduct a proper EIA for ocean discharges. This explanation seems more plausible. In any case, given the content of the assessment report, the RIA does not raise significant issues of violation of the EIA implementation obligation under international law regarding the discharge of treated water into the sea.

However, concerns about reputational damage to marine products due to the discharge of treated water remain strong among fisheries, and it is highly desirable that the Japanese government

maintain ongoing dialogues to gain their understanding. At the same time, it is necessary to enhance the transparency of the RIA data through measures such as strengthening monitoring systems before and after discharges and providing as many opportunities for explanation as possible to neighboring countries such as China, South Korea, and Pacific Island nations that call for the suspension or postponement of the discharge of treated water. (End)