Ocean Newsletter

No.359 July 20, 2015

-

A Movement for Turning Our Thoughts toward the Ocean

Mitsuyuki UNNO Executive Director, The Nippon Foundation / Selected Papers No.20(p.8)

As we approach the 20th anniversary of Marine Day this year the Nippon Foundation is shining light on the various aspects of the ocean and working with the Japanese government and ocean related companies and groups to create a movement in which the thoughts of the Japanese people are turned towards the ocean. In a world of continual change, there are some things we must preserve: Oceans in which diverse forms of life can live together. With gratitude for the oceans, and involving ourselves with them in a variety of ways, universal acceptance of the idea that we humans must protect the oceans is something that must be passed on from generation to generation.

Selected Papers No.20(p.8) -

A Solo Navigation of the Globe on the Darma

Tamio MEGURO Advisor, Albatross Yacht Club (NPO)

Beginning in June of 2005, on a small boat of nine meters length, I set out on a solo navigation of the globe that lasted for three years and ten months.My long journey excluded the poles but took me across five oceans. After traversing the Northern and Southern Pacific, the Northern and Southern Atlantic, and the Indian Ocean, I was able to see things that I couldn't before: floating debris in the ocean, the need for improving conditions for yacht voyaging, and the training of young yachtsmen for the Tokyo Olympics.

-

An Apprentice Boatbuilder in Japan

Douglas BROOKS Boatbuilder / Selected Papers No.20(p.10)

The techniques of boatbuilding, like many crafts, are shrouded in secrecy and were only transmitted via an ancient apprentice system. As a boatbuilder in America working on a variety of projects, I would like to see a revival of ti·aditional boatbuilding in Japan but the traditional apprentice system is not going to be able to save the craft. There is a need now to record a wider range of wasen designs, and offer opportunities for amateur boatbuilders to be exposed to these techniques.

Selected Papers No.20(p.10)

An Apprentice Boatbuilder in Japan

Much of my work as a boatbuilder in the United States has involved collaborating with museums and municipalities, building replicas of traditional boats as public demonstrations. These projects involve researching traditional boat designs, teaching, as well as boatbuilding. I enjoy the varied aspects of this type of work, appreciating both working with my hands as well as engaging the public in a teaching role, and writing about my projects. I also build custom boats for clients and have been involved in restorations of wooden vessels from a Canadian skiff to a three-masted schooner.

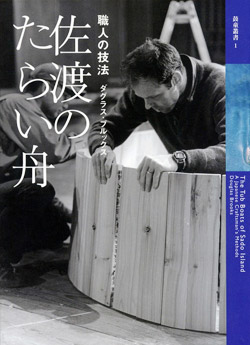

The most significant turn in my professional life occurred in 1990 when I accepted the invitation of my college roommate to visit his native country of Japan. On that first trip I met several boatbuilders, and became exposed to a world of craft both mysterious and alluring. I met craftsmen who possessed extraordinary skills, yet also discovered the craft was only transmitted via an ancient apprentice system. Eventually one of the boatbuilder I met invited me to be his student, and in 1996 he and I built a taraibune, a unique boat still used on a small island in the Sea of Japan. In 2003 the Kodo Cultural Foundation, with funding from the Nippon Foundation, published my first book, The Tub Boats of Sado Island; A Japanese Craftsman's Methods (Shokunin no Gihou; Sado no Taraibune)

Over the course of eighteen visits spanning twenty-five years I have apprenticed with five boatbuilders: in Sadogashima, Urayasu, Tokyo, Aomori, and Okinawa. In addition I have traveled to forty-five of Japan's forty-seven prefectures, meeting and interviewing over fifty boatbuilders. My teachers were in their seventies or eighties at the time I studied with them, and for each I was their sole apprentice. The last century was a pivotal time for this craft: the devastation of World War II forced one more generation to assume the work of their fathers, but the rapid recovery and ascendance of the Japanese economy starting in the 1960's pulled the sons of these men into the corporate jobs of a new Japan. In a single generation the apprentices the craft depended on disappeared.

The techniques of boatbuilding, like many crafts, is shrouded in secrecy. Most of my teachers used no drawings whatsoever, working entirely from memory. Drawings, where they did exist, were left intentionally incomplete. The goal of my work has been to document as much as I can - essentially writing the secrets down - in an effort to preserve the designs and techniques of the craft. My teachers have been willing collaborators in this process, understanding better than anyone the knowledge about to be lost.

My latest research in Japan was in the tsunami zone, documenting the work of Hiroshi Murakami san, one of the last surviving traditional boatbuilders of that region. He built an isobune, the most common small fishing boat of this coast. Prior to 2011, this part of Japan (Sanriku) had the largest concentration of traditional watercraft that I have seen anywhere in Japan. Over ninety percent of the fishing fleet was destroyed or damaged in the disaster, meaning the last victim of the tsunami may be the region's culture. Currently reconstruction projects are taking place throughout the region, with even the smallest fishing harbors receiving larger and higher seawalls. The infrastructure being put in place will hopefully bring this region's important fishing industry back to full capacity. Ironically, the tsunami put Murakami san put him back in business. Since 2011 he built about twenty isobune, though this work tapered off.

Just like my previous projects, I documented as thoroughly as possible Murakami's design and dimensions (sunpo), information that only he knew. It would be impossible to record this information without working directly with him. For instance, all the crucial bevels for various plank angles on the boat were written on the walls of the shop. None of these markings were labeled; only Murakami understood their meaning. As inaccessible as this information may seem, as a boatbuilder I am fascinated with how Japanese craftsmen used their creativity to simplify the layout (sumitsuke) of their designs, a necessity when one is trying to commit to memory all the various dimensions for a boat.

Japan's last generation of boatbuilders worked through an era of incredible change and part of their genius was also an ability to adapt to the transformation of Japan in the post-War period. Murakami san was a working boatbuilder until recently and as such he developed extremely innovative ways to use modern power tools to perform traditional techniques. The pressure to produce boats as efficiently as possible was constant throughout his career. Eventually his work succumbed to competition from mass produced fiberglass (FRP) boats, yet in his techniques, particularly the use of power tools and glue, I see an opportunity to make this style of boatbuilding more accessible to amateurs.

I would like to see a revival of traditional boatbuilding in Japan, like we have seen in Europe and America, but the traditional apprentice system is not going to be able to save the craft. There is a need now to record a wider range of wasen designs, and offer opportunities for amateur boatbuilders to be exposed to these techniques. In the last three years I have built wasen in the Setouchi Festival in Takamatsu and at the Mizunoki Bijutsukan in Kameoka. I taught apprentices for both projects. Earlier this year I built two wasen with students at an American university. I hope to keep publishing my research and find more venues to build wasen and teach these techniques. It is the least I can do to honor the generosity of my own teachers, the last generation of Japanese boatbuilders. Their remarkable skills should not intimidate us, but rather inspire us to find a way to continue this legacy.

Douglas Brooks HP:http://www.douglasbrooksboatbuilding.com/

The Tub Boats of Sado Island: A Japanese Craftsman's Methods (Kodo Cultural Foundation)

The Tub Boats of Sado Island: A Japanese Craftsman's Methods (Kodo Cultural Foundation)

left : An adze with a uniquely curved handle is used.

left : An adze with a uniquely curved handle is used.

right : Mr. Murakami and the author doing the "kikoroshi," or propping the bottom plank in place. (Photo by Angela Robins).