Ocean Newsletter

No.336 August 5, 2014

-

Search and Rescue of Over-ocean Plane Accidents

Akira HONE Research Chief, Japan Institute of Human Factors / Former Airline Pilot

As engine dependability has greatly increased, many twin-engine planes have become able to carry out over-ocean flights. Search and rescue on the open ocean is very difficult, with high labor requirements and costs. However, in order to determine the causes of accidents and prevent their re-occurrence, recovery of the plane's black box and any remains in the ocean is necessary. It is only natural that the public's desire for a safe society calls for the thorough investigation of accidents through searches at sea.

-

California Drought Impacts

Ane D. Deister Vice President Environment and Infrastructure, Parsons Corporation, Sacramento, California

The state of California is currently experiencing conditions of severe drought and water shortages. In January 2014 California Governor Jerry Brown declared a drought state of emergency and directed the state's agencies and departments to take all actions and steps necessary in response to the extremely dry conditions. While policies are urgently needed to address both the drought and water resources, the two main areas that provide the state's water are currently undergoing serious political divisions. The delay caused by their debates and confrontations over water resource management is compounded by the alternating severe drought and flood conditions caused by climate variation, resulting in extreme tensions and confusion for the state.

-

Naval Strategist Alfred Mahan and the Last Shogun, Yoshinobu Tokugawa

Hiroyuki NAKAHARA Visiting Professor, Center for Oceanic Studies and Integrated Education, Yokohama National University / Lecturer, School of Marine Science and Technology, Tokai University

Famous world-wide as a naval strategist, in his youth Mahan served as Lieutenant Commander of a U.S. Naval ship, the USS Iroquois, that was in Osaka Bay during the last days of the Japanese shogunate. After secretly exiting Osaka Castle, Yoshinobu temporarily boarded the Iroquois before making his way to the Kaiyo Maru, which would take him to Edo (Tokyo). At the time, Yoshinobu had with him a letter to the captain of the Iroquois from the U.S. Minister to Japan. The U.S. government thus assisted in Yoshinobu's escape. This is the 100th anniversary of Mahan's death.

California Drought Impacts

California’s highest level policy makers are taking actions that recognize theseriousness of the current drought conditions throughout the state, and the need tomitigate impacts on the urban, farming and environmental water users along the coastand inland communities. Water resource officials declared 2013 the driest year onrecord, and predicted 2014 would bring little change. On January 17, 2014 CaliforniaGovernor Jerry Brown declared a drought state of emergency and directed the state’sagencies and departments to take all actions and steps necessary in response to theextremely dry conditions.

■Folsom Lake, Folsom, California, at 17% capacity (Reuters, images in Bing.)

Folsom lake is adjacent to the capital city of Sacramento, California. The above images are being captured on cell phones by many local residents who have never seen the lake this low before. Being able to walk into the center of this lake is virtually unheard of. Local and state lawmakers only need to look at this lake to see first-hand how serious the drought is for California.

Today the impacts of drought are being felt hardest in the agricultural communities where water restriction policies are taking hold. At the same time, predictions of wildfires in both urban and rural areas are leading to vegetation removal programs and sharing of limited fire protection resources across the state. Water users are being asked to conserve as much as 30% from their past water use, posing difficulties to residents with significant landscape irrigation and water tight areas along California’s coastline. California’s state agencies are undertaking a number of steps to develop and implement more aggressive water conserving and sharing practices. Even before the Governor’s drought emergency declaration, there were a number of executive actions taken as officials recognized that 2013 was shaping up to be among the driest years on record. Collectively these early actions and those imposed by the Governor’s declaration cover the gamut from establishing a Drought Task Force that is reviewing expected water allocations, to taking steps to expedite voluntary water transfers of water and water rights.

While state officials continue to develop strategies and tactics to help mitigate drought impacts, the USGS (United States Geological Survey) is pointing out that there are two different aspects that need to be recognized in developing drought management strategies and response/preparedness plans. One part relates to the water-related impacts that are immediately obvious, including reduced flows of streams and rivers, water level declines in reservoirs, lakes and surface storage, declining water levels in wells and visible surface vegetation drying. But the other aspect relates to the longer-term impacts that accompany these initial visible impacts. As the drought continues these longer-term impacts increase and can be among the most daunting to manage. Issues such as land subsidence, damage to ecosystems and seawater intrusion are among the greatest threats for Californians. Yet, these longer-term impacts are also among the hardest to see, and often get overlooked due to the urgency of the short-term, highly visible impacts. Water utility managers in California have been challenged for decades by salt water intrusion in many locations in the state. In the Central Valley salt build up in the soil from agricultural related chemical applications have led to the need for comprehensive salt management plans. In areas where recycled water is being used to irrigate golf courses, over time the TDS (total dissolved solids) which, are mostly salts associated with Title 22 compliant recycled water, and in turn have led to the need for additional TDS reduction measures.

But the coastal environment is one of the most challenging for utility managers in terms of managing salt water intrusion. The state population in California is estimated at more than 38 million people, and approximately 24 million reside within 10-15 miles of the coastline. The fresh water supplies within the coastal regions are not plentiful and many of the people residing there rely heavily on the exported water supplies from two major sources: Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers and San Francisco Bay Delta, collectively called the Bay-Delta; and the Colorado River (CR). Both of these major sources have been stressed and complicated by significant political interactions, debates, ongoing resource management conflicts, and climate change impacts including oscillating swings between severe droughts and flood events.

Managing the CR in periods of drought are particularly challenging as 7 western US states share in the river’s water supplies. Over many decades there have been federal law suits and numerous executive actions to try and manage the challenges associated with allocations on the Colorado River. Recently the CR endured one of the longest periods of drought in modern times, stressing those resources for many of the states that are continuing to grow and experience water shortages at the same time. In 2010 the stressed CR resources led to the US Bureau of Reclamation to initiate a 2 ? year study to assess the future water supply and demand imbalances of the CR over the next 50 years, and develop and evaluate opportunities to resolve the imbalances. The net effect is that California is not able to rely on the CR to offset the current statewide drought conditions.

Management of the California Bay-Delta has been plagued by decades of water policy conflicts and is often referred to as a highly dysfunctional water management system. The source of the supply is in the northern part of the state and is harvested and operated through an intricate system of reservoirs, surface conveyances and associated pumping facilities to deliver the water to central valley farmers and urban Southern California treatment facilities and ultimately to a wide host of water users. At the same time, the demand for maintaining sufficient fresh water flows into the Bay-Delta estuary to protect and sustain fish and wildlife populations have increased and led to tighter environmental regulations and other curtailments in the quantity and timing of those deliveries.

Because of drought and other low flow challenges in the past, water officials proposed to build a peripheral canal in 1965 to by-pass the Bay-Delta ecosystem and create a more direct delivery mechanism to the Central Valley and Southern California. By the early 1980’s the proposal took form as a ballot measure, pitting southern and northern California voters against one another. That proposal was defeated in 1982. Over time that debate has undergone some change, although today there are strong groups voicing similar beliefs and positions. Still the water conflict challenges remain and the most recent drought conditions have only exacerbated the need to resolve the Bay-Delta conflict. These pressures have culminated in development of the Bay Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP). The BDCP sets up the dual goals of ecosystem protection and water supply reliability, recognizing the need for fresh water for human use and for maintaining the estuarine environment for the Bay-Delta fish and wildlife. It too includes an option of building a canal, and the value of that option is still being debated through public and official comments on the BDCP document. Proponents would argue that it would reduce the existing ecosystem impacts (i.e. provide ecosystem protection) and deliver reliable water to the central and southern California users. The opponents contend that a canal would reduce the overall freshwater flow into the Delta and move the freshwater / saltwater interface further inland, causing damage to the Delta-based agricultural operations and to the estuarine ecosystems. This debate continues to rage and will probably result in a resolution to some degree soon as lawmakers work to place a water bond on the California ballot in November 2014. While the bond total is being debated between $8 billion and 11 billion the bond measure would specify how the $8-11 Billion would be allocated to address water demands throughout the state. Meanwhile, as policymakers debate the water bond, and deciding on what measures are included for funding, the traditional back up supplies of groundwater have also been declining, over-mined, and salt water intrusion is occurring in some areas with few surface water supply options available to them.

For California, 2014 is shaping up to be one of the most challenging years for water users from the coastal communities to the inland desert environments. Yet the scientific climate prediction community is reporting positive news on the global weather front. As recent as April 21, 2014 Global News quoted climatologist Jessica Blunden as saying: “The consensus is right now according to NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, that there is a better than 50 per cent chance that El Nino is going to occur later this summer or fall. One of the things in North America, we tend to have wetter-than-average rainfall across the southern band of the United States,” Blunden said.

Reference: NOAA Climate Prediction Center, appearing electronically in Global News,“Tired of the cold?

Reference: NOAA Climate Prediction Center, appearing electronically in Global News,“Tired of the cold?

El Nino predicted to warm things up”, by Nicole Mortillaro, April 21, 2014(http://globalnews.ca/news/)

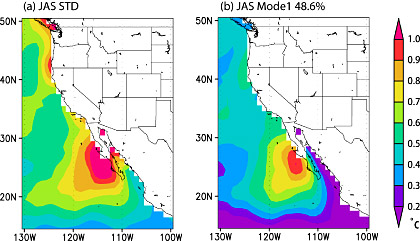

That US-based prediction is in sync with, and supported by, the Asian-based reportentitled “California Nino/Nina” authored by Chaoxia Yuan and Toshio Yamagata, toappear in Scientific Reports of Nature Co, Ltd, on April 25, 2014. In this paper Yuanand Yamagata describe the predicted coastal warming and cooling and point out thatthe “regional air-sea coupled phenomenon seems to be analogous to the well-knownEl Nino/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) in the tropical Pacific but with much smaller timeand space scales, and may be referred to as California Nino/Nina in its intrinsic sense.”

Reference: Figure 2 from Yuan and Yamagata: (a) Lead-lag correlation coefficients between the JASCalifornia Nino/Nina indices and 3-month-running mean SST (shading), SLP (contour) and 10-meterheightwind (vector). Negative (positive) numbers in the top of each panel denote the months that theJAS California Nino/Nina indices lag (lead). (b) is the same as (a) except that the correlationcoefficients are calculated by the JAS California Nino/Nina indices after linearly regressing out thesimultaneous variations related to ENSO. Correlation coefficients with SST and wind significant at the95% confidence level (~0.4) by the two-tailed t test are shown only. The figure was plotted by GrADssoftware.” (Yuan and Yamagata, April 24, 2014)

Reference: Figure 2 from Yuan and Yamagata: (a) Lead-lag correlation coefficients between the JASCalifornia Nino/Nina indices and 3-month-running mean SST (shading), SLP (contour) and 10-meterheightwind (vector). Negative (positive) numbers in the top of each panel denote the months that theJAS California Nino/Nina indices lag (lead). (b) is the same as (a) except that the correlationcoefficients are calculated by the JAS California Nino/Nina indices after linearly regressing out thesimultaneous variations related to ENSO. Correlation coefficients with SST and wind significant at the95% confidence level (~0.4) by the two-tailed t test are shown only. The figure was plotted by GrADssoftware.” (Yuan and Yamagata, April 24, 2014)

Collectively these predictions are positive for California, even though water managerscontinue to brace themselves for one of the worst droughts in its history. While bootson-the-ground water officials continue to predict drought for the near term the scientificclimate community continues to monitor the validity of their models and add value tothe dialog. Many in the western US are watching closely to see how Californiamanages this current water crisis. California water managers contend that crisis leadsto innovation and many see this situation as an opportunity to elevate the need forsustainable, integrated water management even more. Stay tuned for updates andreports as these issues evolve and solutions emerge.