Ocean Newsletter

No.287 July 20, 2012

-

The Beginnings of 21st Century Ocean Conflicts

Keizo TAKEMI Professor, Tokai University Advisor, Basic Act on Ocean Policy Strategic Studies Group

The Basic Act and Basic Plan on Ocean Policy come up for their 5-year review this fiscal year, as stipulated in the Basic Act on Ocean Policy. As we are now entering a new era of ocean related conflicts, I would hope for the rebuilding of a stable, non-partisan political infrastructure and the strengthening of strategic initiatives guided by political leadership, in the best sense, to address such a fundamental aspect of national strategy.

-

Continental Shelf Extension

Shin TANI Cabinet Councilor, Secretariat of the Headquarters for Ocean Policy, Cabinet Secretariat, Government of Japan

In April of this year, Japan received a recommendation regarding the extension of its continental shelf from the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. How will Japan's continental shelf be expanded and what will become of its ocean policy? In this article, I will report on Japan's continental shelf extension and its significance from the perspective of one who has been involved in the extension application process since 2001.

-

Japan's Important Cultural Asset Meiji Maru Needs Funding for Restoration and New Approach to Secure Its Future

Mike GALBRAITH

Journalist, Kokusaika Training ConsultantMarine Day or Umi no Hi which falls on the third Monday of July ※1 - July 16th this year - commemorates the day in 1876 (July 20th) when the Meiji Maru arrived in Yokohama port after a journey from Aomori via Hakodate as the Imperial Yacht carrying the Meiji emperor who was returning from his visit to the Ou district of Tohoku. As Umi no Hi 2012 approaches, the Meiji Maru is in poor condition, closed normally to the public, and the campaign to raise 600 million yen by this March for its renovation raised just half the target amount by the deadline. Against this background, it is surely time to promote a wider discussion about this ship, its unique position as a historic ship and how its future might be made more secure.

Japan’s Important Cultural Asset Meiji Maru Needs Funding for Restoration and New Approach to Secure Its Future

Introduction:

Marine Day or Umi no Hi which falls on the third Monday of July - July 16th this year - commemorates the day in 1876 (July 20th) when the Meiji Maru arrived in Yokohama port after a journey from Aomori via Hakodate as the Imperial Yacht carrying the Meiji emperor who was returning from his visit to the Ou district of Tohoku.

As Umi no Hi 2012 approaches, the Meiji Maru is in poor condition, closed normally to the public, and the campaign to raise 600 million yen by this March for its renovation raised just half the target amount by the deadline. Against this background, it is surely time to promote a wider discussion about this ship, its unique position as a historic ship and how its future might be made more secure.

Meiji Maru’s illustrious history:

The Meiji Maru was especially built for the Japanese government in 1874 by the Robert Napier & Sons shipyard on the River Clyde near Glasgow in Scotland. It was designed as a steamship incorporating the latest engineering technology and, as with all early steamships, also had masts and sails in case the engines failed. In Meiji Maru’s case it was initially rigged as a two-masted topsail schooner. The ship was 225 feet long (68.6 m), 22.6 feet wide (6.9 m), weighed 1,027.57 tons, and could reach a speed of 11.5 knots.

The Japanese government’s plan was to use the ship as a lighthouse tender traveling between the 26 lighthouses planned by Richard Henry Brunton, Japan’s first oyatoi, round Japan’s coastline. However, at the same time, it was also fitted out in Scotland with a magnificently decorated cabin designed for the occasional use by the Meiji emperor and members of his family.

The Meiji Maru performed imperial duties several times during the first half of the Meiji period and also played a key role in the Ogasawara Islands becoming a part of Japan in November 1875.

In 1896 the ship was transferred to the Tokyo Nautical School (now Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology) and two years later was converted into a three-masted training ship moored beside the school and used for training young marine cadets. It lies now on a lawn that was formerly “a large pond?Eon what is now called the university’s Etchujima campus separated from the Sumida River by a wall except for an entrance.

The ship has braved and survived all kinds of threats both on the sea and off it. It was blown ashore three times during typhoons and storms, and immediately after the end of WW2 it was, remarkably, commissioned as the USS Gary Owen by the wife of General Douglas MacArthur and used as a canteen club by the US Red Cross for the occupying US military unit stationed on the campus during which time their neglect resulted in it resting on the bottom of the pond it was floating in.

It is the oldest surviving iron ship in Japan and in 1978 became the only ship to be classified as an Important Cultural Asset. It is surely the crown jewel of Japan’s nautical cultural assets.

Witnessing its gradual physical deterioration:

Visiting the Meiji Maru used to be a delightful experience for me in the early 1990’s shortly after the completion of an extensive restoration of the ship in the 1980’s. For an entrance fee of 100 yen, I could cast my eyes on the beautiful clipper-like lines of its hull and view its three towering masts and elegant bowsprit which never failed to stir my heart. Viewing the accommodation used by the Emperor Meiji, the fascinating old films of Japanese sailing ships at sea, and chatting and exchanging stories with the retired sea hands who looked after the ship as volunteers were experiences to treasure. Even then, I would be often the only visitor and considered the ship to be a hidden gem of a national treasure that no one in Japan seemed to know about.

However, over the last ten years my visits to the Meiji Maru have become increasingly sad experiences as I have observed the once-proud ship gradually “lose its dignity?Eand become reduced to a kind of hulk, albeit a clean and well-cared for hulk. Instead of comparing its lines to great clipper ships of old like the Cutty Sark, I would try to calculate how much the end of the bowsprit had sagged since my previous visit and how long it might be before a large crow landing on the end of it and cause it to break off. I also wondered when someone walking on the deck might accidentally touch against one of the deck structures and crash through its clearly rotten wooden casing.

It was obvious that university has lacked the financial resources to provide such maintenance. The condition of the ship became so bad that finally the masts and bowsprit were trimmed back like dead tree branches and the decision was taken to stop ordinary visitors from embarking on the vessel.

Appeal for donations fails to reach target:

In March 2010 (heisei 21) a campaign was launched to raise 600 million yen (to be hopefully supplemented by a significant top up from the Agency of Cultural Affairs) for the ship’s restoration by the end of March 2012 but, unfortunately, the amount raised by the deadline was less than half: 296,449,481 yen. This has led the university to postpone its restoration plans and to launch a new appeal for donations with the new deadline set as January 2015.

isitor numbers too low to finance ship’s maintenance:

Historic ships are extremely expensive to maintain. For example, according to university officials, the teak deck of the Meiji Maru should ideally be washed down everyday with seawater in order to keep it ship shape. Those managing such ships either need sponsors with deep pockets and/or a lot of paying visitors to finance such maintenance.

The average number of people visiting the Meiji Maru each year has been in the region of 2,500 although the number rose nearly 50% last year partly due to the news coverage of a visit by the Emperor. However, for some time the ship has not even been in a condition good enough for the university to charge visitors. The numbers of visitors and income generated by the ship are poor compared with other historic ships around the world.

In the UK, the Cutty Sark Trust ※1 hopes to attract 250,000 visitors a year paying 12 pounds each to the newly reopened Cutty Sark in London. The SS Great Britain ※2 in Bristol attracts 150,000 visitors a year. Meanwhile in Japan, the Meiji period battleship Mikasa in Yokosuka ※3 drew 190,000 visitors last year with adults paying 500 yen each, and the Nippon Maru (together with the Yokohama Maritime Museum) ※4 claim around 150,000 visitors a year.

Even if the university can succeed is collecting enough donations to restore the ship, will it be able to maintain the ship year by year or will history repeat itself and the ship gradually deteriorate again over a period of say 20 years?

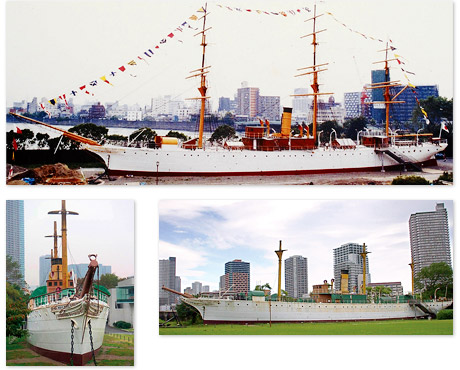

The Meiji Maru photographed in 1988 (above) and again in June of 2012 (below).

The Meiji Maru photographed in 1988 (above) and again in June of 2012 (below).

Could/should the ship be moved?

I have personally felt for a long time that the somewhat inaccessible present location of the Meiji Maru is one of the major causes of the low numbers of visitors and its present sad plight.

If it were to be moved to the old port of Yokohama in the vicinity of the Hikawa Maru, for example, it could surely attract much larger numbers of visitors.

As another alternative, if the plans for the revitalization of Tokyo’s Nihonbashi including the removal of the expressways placed over Nihonbashi river, had progressed faster, I have also often thought that the 60-meter wide Nihonbashi River might also be a great location for the ship to draw a sufficient number of visitors to be able to pay part of its own way.

Moving unseaworthy historic ships may sound impossible but there are many precedents. The above-mentioned SS Great Britain which is much larger than the Meiji Maru was for decades an abandoned wreck in the Falkland Islands before a group raised funds, maneuvered it onto a pontoon and towed it all the way to the UK in 1970.

At this very present time preparations are underway to transport the unrestored hulk of the clipper ship City of Adelaide all the way from Scotland to Adelaide in Australia in order to make it the centerpiece of the restored port of that city.

University officials say that no one has so far suggested moving the Meiji Maru, and that even if they had, the university would never agree. One possible way to overcome the university’s disapproval might be to offer its some special status over some piece of land adjacent to the ship where it can showcase its activities as a university.

Conclusion 1: don’t move it for now at least

For a long time I had been strongly of the opinion that in these difficult economic times the Meiji Maru can only survive long term if it were moved to a location where lots of people could pay to visit it thereby enabling it to earn its keep so to speak.

However, during my research for this article, I came to realize that, in fact, unusually for a ship, the Meiji Maru has barely moved for well over hundred years. The Etchujima campus has clearly been the active home of this vessel for so long that one should not lightly move the vessel from its home.

I had also thought that maybe the university may not want hundreds of visitors each day because they might disturb the university’s academic activities, but I now understand that the ship’s location near the East Gate of the campus means that numerous visitors could enter that gate and leave without being really noticed by the rest of the university.

Conclusion 2: learn from world’s historic ship preservation projects

The Meiji Maru is not just an important cultural asset in Japan but an important part of the world’s maritime heritage.

Managing a historic ship like the Meiji Maru requires a bold vision and expertise in a number of fields including PR, marketing and business management.

I propose that the university boldly seek to acquire or employ at least some of this expertise from similar projects both inside Japan and overseas. They should create a business model to ensure that the Meiji Maru never again reaches its present sad condition.

The very first step towards saving the Meiji Maru, of course, is to raise funds for its restoration to commence as quickly as possible.