Ocean Newsletter

No.226 January 5, 2010

-

Japan's Ocean Policy for the Future

Seiji MAEHARA Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transportation and Tourism (also Minister for Ocean Policy) / Selected Papers No.13(p.23)

Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transportation and Tourism (also Minister for Ocean Policy) It can be said that promoting long-term ocean policy is a top national priority. We have already accomplished, in bipartisan fashion, major marine policy objectives such as the enactment of the Basic Act on Ocean Policy in 2007, the establishment within the Cabinet of the Headquarters for Ocean Policy, and the formulation of the Basic Plan on Ocean Policy in 2008. I believe that gathering together the wisdom of Japan and promoting the use and development of the vast frontier of the ocean will be a new driving force for Japan in terms of industry, technology, and science.

Selected Papers No.13(p.23) -

30 Years of Integrated Coastal Management Experiments in the Mediterranean : some lessons for the future

Yves Henocque

OPRF Visiting Fellow / IFREMERICZM work towards achieving 'optimal sustainable development status,' nearly a decade into the 21st century, is difficult to assess across such a complex geo-political and cultural space as the Mediterranean, but it can be said to be still at a relatively immature stage. ICZM needs to break out of its narrow perception as an environmental activity and adopt new ideas to integrate it with other economic and social policy fields. -

The Ocean and the Spirit of Commerce - A Philosopher Looks at the Ocean from a Functional Perspective

Tadashi OGAWA President, University of Human Environments

Kant acknowledged a unique significance for the ocean. By separating countries, it leads to opposition among them, but it also serves as a medium for their mutual prosperity. This is due to the unification of the ocean and the spirit of commerce, which neutralizes opposition. This view resembles the ideas of Ryoma Sakamoto.

30 Years of Integrated Coastal Management Experiments in the Mediterranean : some lessons for the future

1.National and regional initiatives towards the practical achievement of ICZM in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean has a creditable record of ICZM over the past 30 years. Successive cycles of local ICZM activity and regional coordination have helped establish a substantial knowledge base and track record.

A regional ICZM focal point for the Mediterranean was established over 30 years ago in 1977 in the Priority Actions Programme/ Regional Activity Centre (PAP/RAC) as a key component of the Mediterranean Action Plan (MAP).

PAP/RAC is based in Split, Croatia and is responsible for the co-ordination of the Coastal Area Management Plans (CAMP), under the supervision of MED Unit. The objectives of CAMP are:

- to develop strategies and procedures for sustainable development in project areas;

- to identify and apply the relevant methodologies and tools;

- to contribute to capacity building at local, national and regional levels; and

- to secure a wider use in the region of the results achieved

Tourism pressure - A beach near Algier, Algeria

Tourism pressure - A beach near Algier, Algeria

Under CAMP, practical coastal ICZM management projects were implemented in selected Mediterranean coastal areas. Since 1990 local CAMP projects were implemented in some 17 locations across the Mediterranean. Technical assistance for these CAMP projects was provided by PAP/RAC. In doing so PAP/RAC also supported the development of expertise and experience through the provision of workshops and specialist training, published research, guidelines, technical reports and manuals. A considerable body of knowledge specifically related to the Mediterranean has thus been developed (www.pap-thecoastcentre.org).

On the other hand, within the EU member and accession states ICZM has been supported by both national and EU funded actions (under the LIFE, community initiative, neighbourhood and pre-accession programmes, notably in the EU Demonstration Programme on ICZM 1997-2001). The EU Recommendation on ICZM has requested national ICZM strategies from each member state, although progress on this has been slow.

Further progress towards ICZM in the Mediterranean is based on the evolution of the Short and Medium-term priority Action Programme (SMAP) from 1995. The Barcelona Declaration, adopted on 28 November 1995 at the Euro-Mediterranean Conference of Ministries of Foreign Affairs, laid down the foundations of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership established between the European Union and the then 12 Southern and Eastern Mediterranean Partners (Algeria, Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, Jordan, Malta, Morocco, Palestinian Authority, Syria, Tunisia, and Turkey). Based on the Barcelona Declaration, the 1st Euro-Mediterranean Ministerial Conference on Environment held in Helsinki (28 November 1997) adopted in its Declaration the Short and Medium-term priority Action Programme (SMAP). Helsinki defined the following fields of action for SMAP:

- Integrated water management

- Waste management

- Pollution Hot Spots

- Integrated coastal zone management

- Combating Desertification

SMAP was implemented through three consecutive phases under which 26 projects have been selected and funded. SMAP III, from June 2004, is the most recent phase and had a specific focus on sustainable development and ICZM. It had three components:

- 8 ICZM field projects, with a duration of 24 to 36 months, starting in January 2006

- "Promoting awareness and enabling a policy framework for environment and development integration in the Mediterranean" project implemented by UNEP/MAP

- A cross-cutting Technical Assistance (TA) component.

Thus, under SMAP III, conventional local action in the form of ICZM action plans (but not their implementation) was combined with the macro level "Promoting awareness and enabling a policy framework for environment and development integration in the Mediterranean” - an attempt to create a macro-level enabling framework through national Policy Briefs and the ICZM Protocol. This second objective was to promote awareness on the value and state of the coasts, and to provide support to countries in strengthening and modifying the existing national-level enabling environment, including policy, institutional and legislative frameworks.

At the regional (Mediterranean basin) level, the 7th Protocol of the Barcelona Convention, the Protocol on Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM), was signed in Madrid, in January 2008. It provides an ambitious regional context under which countries will better manage their coastal zones, as well as deal with the emerging coastal challenges, such as climate change. Its importance lies in the mutual recognition of the severe pressure of development around the Mediterranean coasts and the urgent need for coordinated action and governance. The challenge of full ratification into the many national legal structures lies ahead.

The Protocol provides a clear and precise 'menu' of actions for each state to deliver:- defining the coastal zone

- defining the coastal setback

- formulation and development of coastal strategies

- formulation of Environmental Impact Assessment for public and private projects

- and Strategic Environmental Assessment

- developing policies for preventing natural hazards, particularly those resulting from climate change

- applying the ecosystems approach to coastal planning and management

- reporting on the implementation of the Protocol, including measures taken, their effectiveness and the problems encountered upon their implementation.

The Protocol provides a unique and unparalleled foundation upon which to base future action. The achievement of a consensus on the way forward for such a complex enclosed sea is a considerable achievement. The implications for future ICZM priorities in the Mediterranean are:

- The central dilemma of such an international protocol is that the responsibility for its delivery is largely devolved to the national level with all the ratification, adoption and implementation problems that implies.

- There remains an important function of central coordination, monitoring and support to be fulfilled. Such support could substantially aid the achievement of the Protocol's objectives.

2. Future progress towards ICZM in the Mediterranean and lessons learned

The challenge for the future is to build on the Protocol, from the 'the top down' and the experience of practical projects from the 'bottom up' to facilitate and embed ICZM processes across the whole Mediterranean - to take ICZM beyond the constraints of the short-term project cycle within limited and isolated geographical spaces to a long-term sustained process which:

- enhances governance capacity in terms of reproducibility

- contributes to a long-lasting approach

- transfers to other geographic units

- can be progressively scaled-up as the basis for a coherent national policy

Put simply, the Protocol articulates an ambition to raise the entire Mediterranean coast to an optimal sustainable development status. The central challenge to all parties is to operationalise this ambition.

Progress towards achieving this 'optimal sustainable development status,' nearly a decade into the 21st Century, is difficult to assess across such a complex geo-political and cultural space as the Mediterranean. In addition, ICZM is a multi-layered activity including practical implementation, institutional strengthening, governance frameworks, etc. Possibly because of this complexity there have been very few attempts to assess the outcomes of the ICZM process. Sustainable development is the stated goal of all the ICZM activity to date in the Mediterranean, yet typically very little is said about how progress towards this ultimate objective is to be achieved or how progress is measured. This was recognised in the RED1, which explicitly mentions, amongst the weaknesses related to lack of policy assessment, those concerning the impact assessment of plans and programmes.

However, the considerable experience and body of knowledge garnered from project activity and the conventions such as the ICZM Protocol, the Mediterranean Strategy for Sustainable Development, etc., means that the journey towards achieving this objective is well underway.

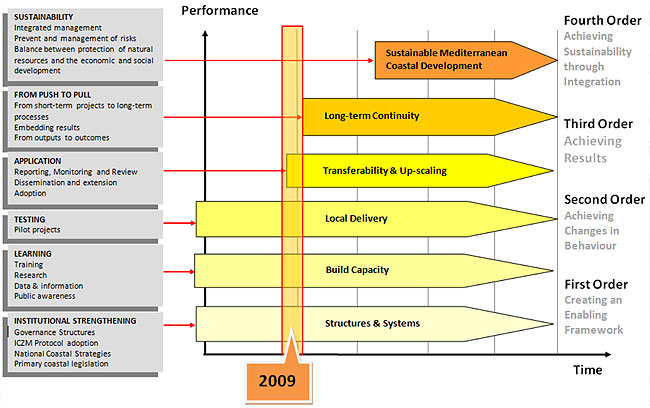

Despite the lack of quantifiable indicators and measures of progress, a review of activity to date indicates that ICZM's progress towards achieving sustainable coastal development is still at a relatively immature stage. This is summarised in the diagram below:

Figure 1: Status of ICZM, 2009

Figure 1: Status of ICZM, 2009

Many descriptions exist of the process by which ICZM programmes are constructed and evolve. A widely used framework was developed by the Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection (GESAMP, 1996)2 adapted for use for the SMAP III ICZM projects. The GESAMP cycle begins with an analysis of problems and opportunities (Step 1). It then proceeds to the formulation of a course of action (Step 2). Next is a stage when stakeholders, managers, and political leaders commit to new behaviours and allocate the resources by which the necessary actions will be implemented (Step 3). This involves formalization of a commitment to a set of policies and a plan of action and the allocation of the necessary authority and funds to carry forward the implementation of these policies and actions (Step 4). Evaluation of successes and failures, learning, and a re-examination of how the issues themselves have changed complete the management cycle (Step 5).

The reality of many coastal management programmes of all varieties is that we often see only fragments of unconnected processes. In particular, there may be a major gap between repeated efforts at issue analysis and planning (Steps 1 through 3) and the implementation of a plan of action (Step 4). Moreover, subsequent initiatives often do not build strategically on a careful assessment of what can be learned from earlier attempts to address the same or similar issues (Step 5). Experience demonstrates that in complex coastal systems well-designed and well-executed processes may not produce the desired outcomes. This is the challenge for the future of ICZM in the Mediterranean, i.e., to build on existing activities to provide an "enabling framework" to facilitate the embedding of ICZM processes across the whole Mediterranean, thereby taking ICZM beyond the constraints of the short-term project cycle.

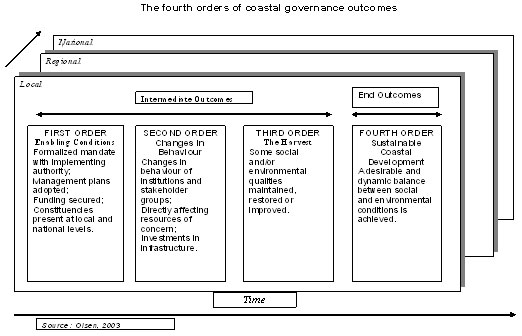

To transcend the short-term project cycle "trap", one may use the Orders of Outcomes framework proposed by Olsen (2003)3 and tested in several parts of the world, including South-East Asia (Henocque & Tandavanitj, 2009)4 and Latin America (Olsen, 2009)5 . The Orders of Outcomes framework (Figure 2) focuses on the sequence of outcomes that should be achieved to move toward sustainable development in coastal areas.

Figure 2: The Four Orders of Coastal Governance Outcomes

Figure 2: The Four Orders of Coastal Governance Outcomes

Currently ICZM is inadequatelyequipped to meet the challenges faced by the Mediterranean. To move towards theFourth Order of sustainable coastal development in the Mediterranean, a numberof critical barriers must be overcome,including:

- the short-term, stop-go nature of the individual projects based on the project funding cycles that has led to a loss of essential continuity and capacity;

- the relentless and overwhelming pace of development along the coast that has led to a gap between the rapid, exponential rate of development with its consequent environmental degradation, and the capacity of ICZM to deal with it: the development-management gap;

- the stubbornly persistent perception of ICZM as an environmental management activity --a pressing need existsto embed ICZM into other areas of policy;

- the still patchy and inconsistent enabling frameworks for national capacity building and regional actions such as awareness-building, that takes place in parallel and often behind local action;

- the obvious lack of synergy between programmes;

- the relatively poor public visibility of ICZM projects;

- Poor communication and networking: spreading the word and networking between local projects must be supported through initiatives like the PEMSEA Local Governments Network or the EU Venice Platform and its Stakeholder Forum;

- the need to re-assert ICZM as the powerful arbiter it is between the land and sea issues and interests;

- the over-long time cycle to produce local ICZM action;

- the failure ofICZM to grasp the imagination of politicians in particular and the community in general. "Demystifying" the concept is a priority through using a simplified and positive terminology as proposed in the Mediterranean ICZM Marketing Strategy6;

- the lack of vision at the regional scale is replicated at the local level.A simple, practical vision of what constitutes a "sustainable coast", comparable to the clear objectives of examples such as the Millennium Development Goals, is urgently required;

- the remaining lack of appropriate national legal frameworks for ICZM.

3. Towards the future

Achieving the fourth order of outcomes (sustainable coastal development)requires not just a substantial increase in the level of ICZM activity aroundthe Mediterranean, it requires significant changes in the culture of theactivity and its ability to adapt and work with an ever-changing policybackground.

As discussed earlier ICZM needs to break out ofits narrow perception as an environmental activity and integrate with othereconomic and social policy fields. Only by doing this will ICZM be considered a relevant tool forsustainable development of the coast.

In general, existing ICZMguidance in the Mediterranean and other regions is predominantlyenvironment-led and can appear pre-occupied with the impacts of tourism and themanagement of habitats and eco-systems; much space is devoted to assurancesthat ICZM is ‘not incompatible’ with social and economic objectives, but withlittle real attention to integrating these objectives. In addition, the guidance available isbecoming dated as the last decade has seen a plethora of internationalagreements on the environment, pollution, poverty reduction, health, climatechange and other issues. "ICZM hasn't yet captured the policy and practice high ground its proponents would wish and lacks apparent and contemporary relevance to politicians and other key decision makers".7

Maritime spatial planningis seen as a key tool in moderating competing developmental demands. In theMediterranean region, spatial planning systems have been poorly developed;however, it is likely that they will steadily improve in the coming years, withstronger mandatory requirements specific to each of the land and marineenvironments. ICZM has an importantrole to play in this process, in particular in moderating between marine andterrestrial uses and interactions. ICZMpractitioners will need to be able to work closely with, and use maritimespatial planning as a tool, and be familiar with use of the StrategicEnvironmental Assessment (SEA) and other spatial planning tools.

Critically embracing thiswider agenda will require an influx of ICZM practitioners with new andunfamiliar skills. Current ICZM practitioners and their supportingorganisations in the Mediterranean are predominantly from an environmental andscientific background. This is mirrored in the audiences at conferences,workshops and training courses. A wider skills base and constituency will berequired in the future, including, for example: community development,economics, spatial planning and climate change.

This realignment will have totake into consideration recent challenges to the current ICZM dogma, which leadsto the expectation of simple solutions to most of the complex and increasinglyglobal problems facing the world’s coastal zones. Tackling those in a morecomprehensive way in a rapidly changing world necessitates suchnew thinking as"adaptive management"8 to keep ICZM as a key concept for adaptation.

- A Sustainable Future for the Mediterranean, the Blue Plan's Environment and Development Outlook, 2005

- GESAMP (1996): The contributions of Science to Integrated Coastal Management. Reports and studies No.61. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- Olsen, S.B. (2003): Frameworks and indicators for assessing progress in integrated coastal management initiatives. Ocean & Coastal Management 46, 347-361.

- Henocque, Y. & Tandavanitj, S. (2009): CHARM, Coastal Habitats and Resources Management Project in Thailand and Mainstreaming of Co-management Practices into Policies. LOICZ Inprint, Issue 1 (www.charmproject.org), 23 pages.

- Olsen, S.B.; Page, G.G. & Ochoa, E. (2009): The Analysis of Governance Responses to Ecosystem Change: A Handbook for Assembling a Baseline. LOICZ Reports & Studies No.34. GKSS Research Center, Geesthacht, 87 pages.

- Iczm marketing strategy, Priority Actions Programme/Regional Activity Centre, Split, November 2006

- UNEP/MAP SMAP III Project: iczm Marketing Strategy, Priority Actions Programme/Regional Activity Centre. Split, November 2006

- Mee L.D. (2005). Assessment and monitoring requirement for the adaptive management of Europe's regional seas. In: Vermaat J.,Bouwer L., Turner K., Salomons W., Editors. Managing European Coasts. Springler-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 227-237