News

Essays and Commentary

Blue carbon collaboration at COP30: Technical outcomes and pathways

2025.12.26

On 11 November 2025, the Ocean Pavilion at COP30 in Belém hosted the session “Blue Carbon Collaboration: Sharing Japan’s Coastal Solutions with Asia and Beyond (Including Marine CDR Pathways)”, organised by the Ocean Policy Research Institute of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation (OPRI-SPF). The session examined how coastal nature-based solutions (NbS)—including seaweed ecosystems and seaweed farming, tidal flats, mangroves, seagrass meadows and tidal marshes can function as integrated climate-repair strategies within emerging marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR) portfolios, while simultaneously delivering measurable ecological and socio-economic co-benefits.

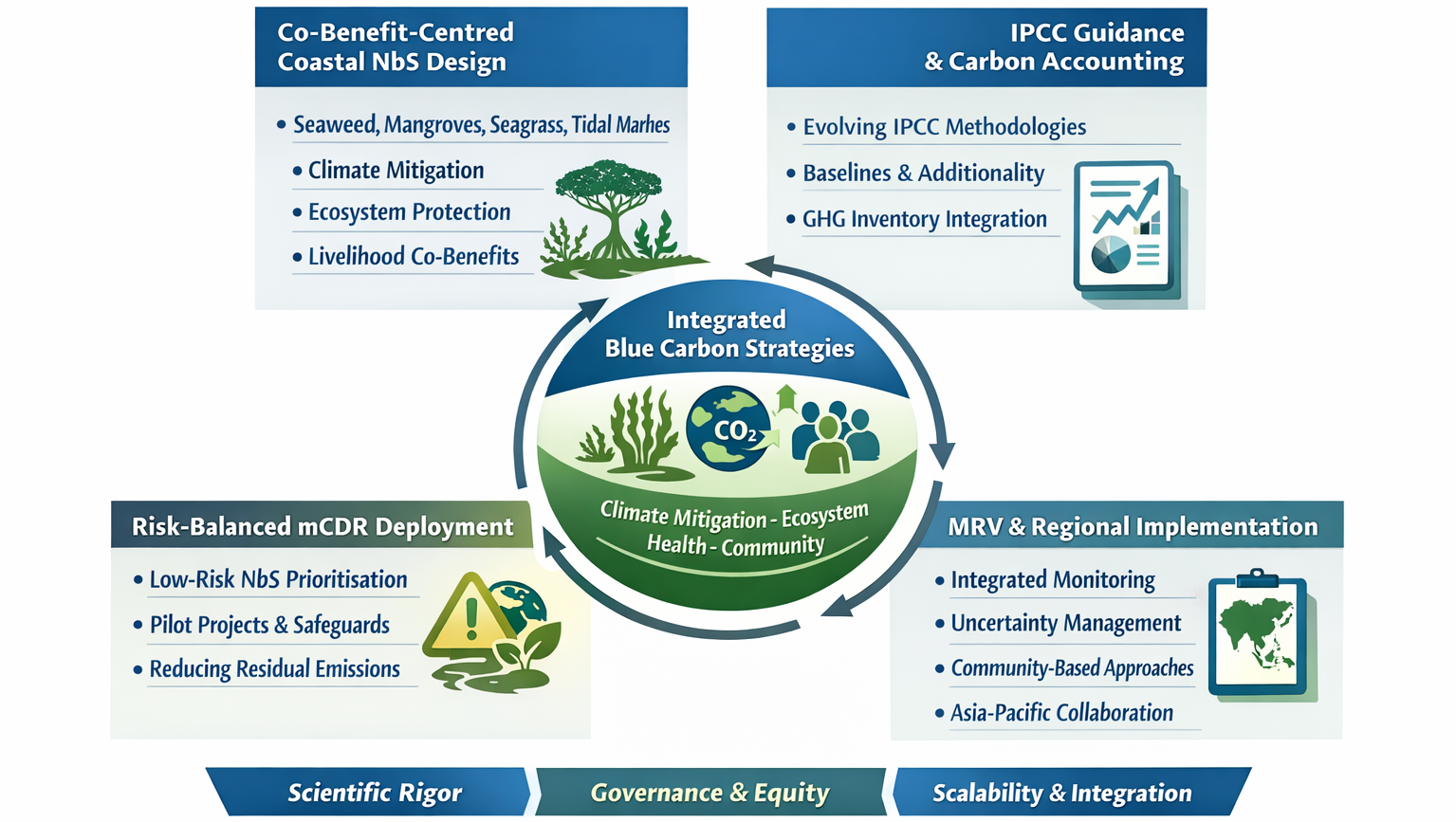

Rather than serving as a forum for project reporting, the session focused on technical and methodological questions central to the credibility and scalability of blue carbon interventions. Discussion converged on four interlinked dimensions: (1) co-benefit–centred design of seaweed and coastal NbS, (2) evolving IPCC guidance for carbon dioxide removal and carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CDR/CCUS), (3) risk-balanced deployment of mCDR under conditions of climatic urgency, and (4) integrated monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) frameworks and implementation pathways, with particular emphasis on Asia.

Rather than serving as a forum for project reporting, the session focused on technical and methodological questions central to the credibility and scalability of blue carbon interventions. Discussion converged on four interlinked dimensions: (1) co-benefit–centred design of seaweed and coastal NbS, (2) evolving IPCC guidance for carbon dioxide removal and carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CDR/CCUS), (3) risk-balanced deployment of mCDR under conditions of climatic urgency, and (4) integrated monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) frameworks and implementation pathways, with particular emphasis on Asia.

1. Co-benefit–centred design of seaweed and coastal NbS

Dr. Atsushi Watanabe (Ocean Policy Research Institute of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation) presented Japan’s blue carbon initiatives as a systemic model in which seaweed beds, seaweed farming and other coastal NbS are conceptualised as multi-output climate infrastructure rather than single-purpose carbon offset projects. In this framing, climate mitigation, ecosystem integrity and community well-being are jointly optimised rather than treated as competing objectives.

Figure 1. Integrated blue carbon strategy framework: co-benefit design, IPCC accounting, risk- balanced mCDR, and MRV pathways.

Seaweed beds, tidal flats, mangroves, seagrass meadows and tidal marshes were discussed as systems to be designed and evaluated against three tightly coupled outcome domains:

(A) climate mitigation quantified over the full life cycle,

(B) ecosystem integrity including biodiversity and coastal protection, and

(C) community and economic co-benefits such as livelihoods, employment and stewardship.

A central message was that co-benefits are not ancillary but constitute a core criterion of technical robustness. Projects were characterised as credible only where co-benefit objectives are explicitly defined, monitored through measurable indicators, and embedded within governance arrangements that ensure equitable benefit sharing.

(A) climate mitigation quantified over the full life cycle,

(B) ecosystem integrity including biodiversity and coastal protection, and

(C) community and economic co-benefits such as livelihoods, employment and stewardship.

A central message was that co-benefits are not ancillary but constitute a core criterion of technical robustness. Projects were characterised as credible only where co-benefit objectives are explicitly defined, monitored through measurable indicators, and embedded within governance arrangements that ensure equitable benefit sharing.

2. Scientific perspectives on seaweed blue carbon pathways and climate sensitivity

Prof. Ana Queirós provided a focused scientific perspective on the specific challenges and opportunities associated with seaweed blue carbon. She emphasised the importance of distinguishing between autochthonous carbon, fixed and stored within the same ecosystem, and allochthonous carbon, whereby carbon fixed by macroalgae is exported and ultimately sequestered elsewhere, particularly in marine sediments or the deep ocean.

She noted that, unlike mangroves or seagrass meadows, the mitigation potential of seaweed systems often depends on spatially decoupled processes of biomass export, transport and deposition. As a result, credible accounting requires explicit consideration of carbon fate beyond the site of production. Prof. Queirós highlighted substantial progress made over recent years through the application of particle tracking models, which have improved understanding of transport pathways and sedimentary sequestration of seaweed-derived organic carbon. However, she stressed that further empirical validation and model intercomparison are required to strengthen confidence in sequestration estimates.

She also underscored that species, habitats and biogeochemical processes central to potential seaweed blue carbon projects are highly sensitive to climate variability and change, including marine heatwaves, storm regimes and shifts in ocean circulation. Offshore seaweed farming, while offering opportunities for scale, introduces additional exposure to physical disturbance and climatic extremes. Consequently, she emphasised the need for climate-aware design, adaptive management and robust MRV to avoid overestimating permanence and durability of sequestration.

She noted that, unlike mangroves or seagrass meadows, the mitigation potential of seaweed systems often depends on spatially decoupled processes of biomass export, transport and deposition. As a result, credible accounting requires explicit consideration of carbon fate beyond the site of production. Prof. Queirós highlighted substantial progress made over recent years through the application of particle tracking models, which have improved understanding of transport pathways and sedimentary sequestration of seaweed-derived organic carbon. However, she stressed that further empirical validation and model intercomparison are required to strengthen confidence in sequestration estimates.

She also underscored that species, habitats and biogeochemical processes central to potential seaweed blue carbon projects are highly sensitive to climate variability and change, including marine heatwaves, storm regimes and shifts in ocean circulation. Offshore seaweed farming, while offering opportunities for scale, introduces additional exposure to physical disturbance and climatic extremes. Consequently, she emphasised the need for climate-aware design, adaptive management and robust MRV to avoid overestimating permanence and durability of sequestration.

Figure 2. Left: Panel discussion during the Blue Carbon Collaboration: Sharing Japan’s Coastal Solutions with Asia and Beyond (Including Marine CDR Pathways) session at the Ocean Pavilion, COP30 (Belém); Right: Sample of a J-Blue Credit certificate.

3. Evolving IPCC guidance for carbon dioxide removal and carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CDR/CCUS)

Prof. Bong-Oh Kwon (Kunsan National University) linked national experiences to the evolving global methodological landscape through his participation in the 63rd Session of the IPCC in Peru. He reported that forthcoming IPCC documentation is expected to explicitly address seaweed ecosystems, including seaweed farming, as well as tidal flats, as components of carbon capture and removal.

He emphasised that formal inclusion would require robust baselines reflecting natural variability and prior ecosystem use, clear additionality criteria particularly where existing aquaculture is repurposed for climate objectives and consistency with national greenhouse gas inventory methods. Such developments would elevate seaweed-based NbS from emerging practices to recognised components of international climate accounting frameworks.

He emphasised that formal inclusion would require robust baselines reflecting natural variability and prior ecosystem use, clear additionality criteria particularly where existing aquaculture is repurposed for climate objectives and consistency with national greenhouse gas inventory methods. Such developments would elevate seaweed-based NbS from emerging practices to recognised components of international climate accounting frameworks.

4. Risk-balanced deployment of mCDR under conditions of climatic urgency

Prof. Shaun Fitzgerald (Centre for Climate Repair, University of Cambridge) framed mCDR within the context of finite global carbon budgets and accelerating climate risks. He argued that, given residual emissions from hard-to-abate sectors, mCDR will be necessary as part of broader climate repair strategies, but must be pursued with caution and robust governance.

He advocated for risk-balanced portfolio approaches in which lower-risk NbS such as seaweed ecosystems, mangroves, seagrass meadows, tidal flats and tidal marshes are prioritised where co-benefits and safeguards are clear, while more uncertain or intrusive mCDR options proceed only through tightly governed pilots. All mCDR approaches, he stressed, must complement rather than substitute for rapid emissions reductions.

He advocated for risk-balanced portfolio approaches in which lower-risk NbS such as seaweed ecosystems, mangroves, seagrass meadows, tidal flats and tidal marshes are prioritised where co-benefits and safeguards are clear, while more uncertain or intrusive mCDR options proceed only through tightly governed pilots. All mCDR approaches, he stressed, must complement rather than substitute for rapid emissions reductions.

5. Integrated monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) frameworks and implementation pathways, with particular emphasis on Asia

A cross-cutting outcome of the session was the articulation of requirements for integrated MRV frameworks capable of supporting both coastal NbS and mCDR. The discussion converged on the need for MRV systems that span multiple ecosystems within a single accounting architecture and integrate carbon, ecological and socio-economic indicators.

Particular emphasis was placed on addressing uncertainty, leakage and risks of reversal, especially for seaweed-based systems where sequestration may occur far from production sites. Embedding community-based monitoring was also identified as critical for enhancing data quality, legitimacy and local relevance.

Particular emphasis was placed on addressing uncertainty, leakage and risks of reversal, especially for seaweed-based systems where sequestration may occur far from production sites. Embedding community-based monitoring was also identified as critical for enhancing data quality, legitimacy and local relevance.

Asian implementation and regional integration

Dr. Santosh Kumar Rauniyar (OPRI-SPF) focused on translating these technical insights into operational pathways for Asia, a region characterised by extensive seaweed cultivation, high coastal population density and acute climate vulnerability. He emphasised Asia’s strategic importance for integrated NbS–mCDR strategies and proposed a regional pathway involving technical collaboration on MRV, co-designed pilot projects with coastal communities, integration into nationally determined contributions and adaptation plans, and mobilisation of public and private finance.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the session articulated a rigorous and integrated blueprint for advancing seaweed farming and other coastal NbS as credible, co-benefit–driven components of marine carbon dioxide removal. By combining systems-based project design, emerging IPCC guidance, risk-balanced mCDR deployment and strengthened scientific understanding of seaweed carbon pathways and climate sensitivity, the session clarified both the promise and the conditions under which seaweed blue carbon can meaningfully contribute to climate mitigation. These outcomes have direct relevance for MRV development, IPCC processes and the responsible scaling of blue carbon initiatives across Asia and beyond.

(Santosh Kumar Rauniyar, Research Fellow, OPRI-SPF)