Ocean Newsletter

No.498 May 5, 2021

-

Traveling the World’s Oceans on the Traditional Sailing Canoe, Hōkūleʻa

UCHINO Kanako

Supervisor, Miura Ocean Academy

The Hōkūleʻa is a traditional Hawaiian sailing canoe which only uses the stars, waves, wind, and other forces of nature instead of instruments like a compass to navigate islands beyond the horizon. I will here give a summary of the traditional sailing technique of navigating by the stars, as well as introduce our activities to date and the relationship between people and nature.

-

Kaisou Oshiba’s 30-Year Journey: Welcome to the Forest of the Ocean

NODA Michiyo

President, Kaisou Oshiba Society

/ Selected Papers No.27(p.12)

Seaweed, the “Forest of the Ocean” that nurtures life, has a rich diversity of colors and shapes as a result of adapting to environments at various depths. Kaisou Oshiba, where you can learn about this diversity and enjoy gaining hands-on experience, began over 30 years ago at the University of Tsukuba’s Shimoda Marine Research Center. Environmental learning workshops are now being held at many different locations for a wide range of age groups.

Selected Papers No.27(p.12) -

Practical Studies in Marine Science at Tokai University’s School of Marine Science

YAMADA Yoshihiko

Provost,Shizuoka Campus , Tokai University.Since its establishment in 1962, Tokai University’s School of Marine Science and Technology has placed great importance on practical studies in marine science, and has been training maritime personnel in a wide range of ocean-related fields for 58 years. Ocean education, having become highly specialized, requires collaboration and coordination among the various areas. Our School is aiming to further advance the comprehensive ocean education curriculum implemented thus far, as well as nurture individuals who can make contributions to a maritime nation.

Kaisou Oshiba’s 30-Year Journey: Welcome to the Forest of the Ocean

Seaweed, the “Forest of the Ocean” that nurtures life, has a rich diversity of colors and shapes as a result of adapting to environments at various depths.

Kaisou Oshiba, where you can learn about this diversity and enjoy gaining hands-on experience, began over 30 years ago at the University of Tsukuba’s Shimoda Marine Research Center.

Environmental learning workshops are now being held at many different locations for a wide range of age groups.

My First Encounter with Seaweed Specimens

The University of Tsukuba's Shimoda Marine Research Center is located in a small emerald green inlet in Nabeta Bay, Shimoda City, at the tip of the Izu Peninsula. I first visited Dr. Yasutsugu Yokohama’s laboratory more than 30 years ago. At the time, he was an assistant professor of seaweed physiology and ecology. The meeting was held at the request of my former workplace, the Design Division of the Industrial Research Institute of Shizuoka Prefecture (now the Industrial Research Institute of Shizuoka Prefecture), to discuss drawings for a photosynthesis measuring instrument called "Product Meter.”

We were on the second floor of the research building closest to the ocean, in a laboratory with a reception area. A small plaque hanging on the wall caught my attention, so after we finished our business, I asked, "What's the red thing in the plaque?" He replied, "It's a variety of seaweed called habutaenori (Marionella schmitziana). I’ve collected some other samples as well." He then took some samples out from a specimen shelf in the next room and showed them to me. Some of the seaweed had sand still stuck to it, and there was a faint scent of the ocean. "The seaweed is stuck to the paper! There are so many different colors and shapes! I never knew there were so many kinds!" Seeing so many seaweed specimens for the first time made quite an impact on me.

Perhaps due to my surprised delight, Dr. Yokohama asked me, "I know it's a bit far, but would you be willing to help me with my seaweed research one day a week, or even help me from home?” I was above all deeply curious about the “Forests of the Ocean.” This was how my “dialogue with seaweed” began, together with the seasonal changes of fresh greenery and autumn leaves of Amagi Pass as I commuted from my home in Shuzenji.

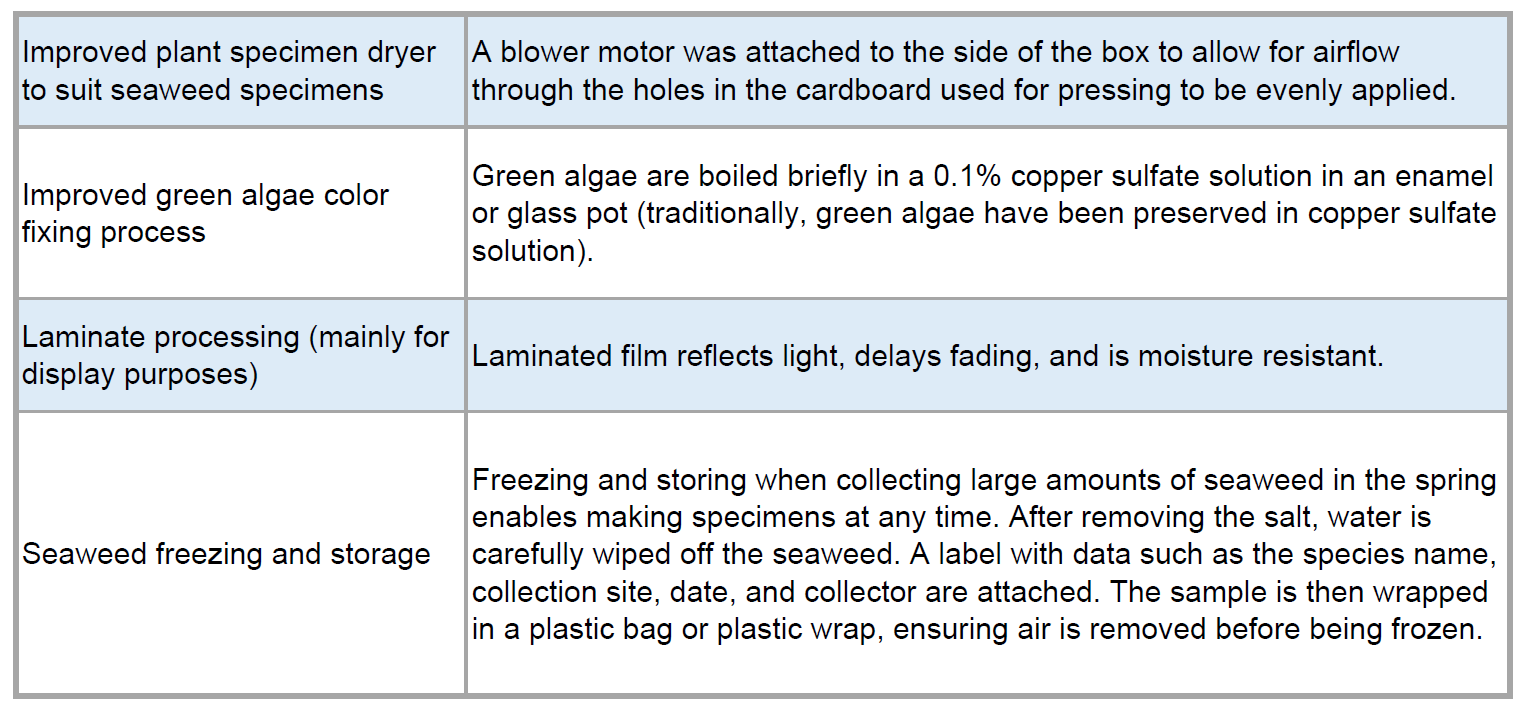

Improvements to Help Produce Beautiful Specimens

After the arrival of Admiral Perry’s black ships in 1853, several specimens of seaweed that his fleet collected in Shimoda Bay were introduced to the world. Although seaweed specimens had been created in various parts of Japan before his arrival, I have heard that the Yokohama Laboratory has improved on the traditional methods (see table). The key to creating beautiful specimens is to dry the seaweed, which contains a lot of water, quickly. Color fixing is also essential. Chlorophyll is green because magnesium is bound to it. However, the chemical bonds are weak, and the magnesium is easily dislodged, causing the green to fade away quickly. When seaweed is boiled in a solution of copper sulfate, the magnesium in the chlorophyll is substituted by copper, which preserves the green color longer. Seaweed specimens that are beautifully preserved can be identified relatively easily so that species names can be determined quickly. These specimens are also suitable for display.

Points improved upon during the development of kaisou oshiba

Points improved upon during the development of kaisou oshiba

The Spread of Kaisou Oshiba

After producing the specimens, the remaining seaweed is frozen for storage, but many samples are incomplete in shape. Attempting to combine torn seaweed samples was the beginning of kaisou oshiba art (Fig. 1). Thirty years have passed since the University of Tsukuba's Biology Degree Program first incorporated seaweed pressing into its 4-night, 5-day plant field training program at the Shimoda Marine Research Center. After creating specimens, students at the training program use them to produce their own postcards and bookmarks. They become completely engrossed in producing this art, which features unique colors and forms. On the last day of the field training, we give them the finished products, which are dried and laminated. Many of the students comment how much they enjoyed seaweed pressing, with it becoming a good memory of their visit to Shimoda. Eventually, seaweed pressing was incorporated into classes at elementary, junior high, and high schools around the country. It also became a popular program as part of lifelong learning efforts for the general public in Shimoda City and other municipalities in the Izu Peninsula. As a result, the circle of people creating these beautiful works of art has spread nationwide. This increase in popularity meant that instructors needed to be trained, so we established the Kaisou Oshiba Society. Study sessions are now held twice a year thanks to the support of Dr. Yokohama and other advisors, all of whom specialize in algae. The sessions include a hands-on practical class in the spring and a lecture in the fall. Currently, about 30 certified instructors are teaching this topic at facilities and schools across the country.

Figure 1: Michiyo Noda, Square

Figure 1: Michiyo Noda, Square

Kaisou Oshiba as a Form of Environmental Education

The current seaweed pressing class consists of two hours of lectures and hands-on practical training. The venues are lined with various panels of seaweed specimens, including familiar large varieties such as wakame and hijiki, to elicit reactions from participants as they enter the venue. Seeing these beautiful and fun works of art helps change the rather plain image people have of seaweed. Seeing examples of past participants' work also raises participants’ expectations for the class.

First, a DVD called "Welcome to the Forests of the Ocean!” (11 min.) is shown to provide an introduction to the topic (Fig. 2). It uses easy-to-understand language to introduce the critical role of underwater forests and seaweed beds in various parts of Japan and their connection to the land. For many participants, this is their first introduction to the underwater forests. Participants then make pressed seaweed postcards. The classroom and the large hall become quiet as everyone focuses on this hands-on activity. During one class, a teacher murmured, "I wish my students were this enthusiastic about my classes.” A middle-aged participant in the general hall commented, “I’ve never concentrated so hard in my life!” All of the participants become absorbed in seaweed pressing.

Most of the seaweed used to make the postcards is collected from the beach. If you go to the beach the day after a tidal surge in spring, you can pick up a wide variety of colorful seaweed. We choose nine types of seaweed consisting of green, brown, and red algae for the classes. We then freeze them for year-round use.

Some seaweed is so delicate that their forms would be impossible on land, while others are colorful even though they only have leaves and no flowers. The shapes and colors of seaweed result from their adaptations to living underwater. The reason that wakame and kelp are brown and that yukari (Plocamium telfairiae), which grows in deep water, is bright red is because they contain red pigment. This red color is complementary to green, allowing it to capture and utilize the green light that reaches the deepest parts of the ocean. Sunlight, which is vital for seaweed, has a hard time reaching the deeper levels of the ocean when the water is cloudy. Dr. Yokohama even invented a catchphrase: "Light is food. Don't pollute the ocean!”

Dr. Yokohama passed away in 2018, but in 2020, 32 classes, five exhibitions, and one lecture were held on pressed seaweed, which he first invented at the Shimoda Marine Research Center. The kaisou oshiba art has become an accessible introduction to the beauty of seaweed (Fig. 3). Thanks to this success, we received requests from an Australian aquatic plant society a few years ago and from a Korean pressed flower organization in 2020, meaning the project has spread overseas. Recently, we have been holding annual exhibitions of pressed seaweed at museums and art galleries in Japan, and we want to focus on creating new works in the future. Our society hopes to work with certified instructors to expand our classes as a form of environmental education in Japan and overseas. (End)

Figure 2: Forests of the Ocean (Underwater forest)

Figure 2: Forests of the Ocean (Underwater forest)

Figure 3: Kaisou oshiba class at the Tokyo Bay Festival held every year at the Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse

Figure 3: Kaisou oshiba class at the Tokyo Bay Festival held every year at the Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse

- Kaisou Oshiba Society Website http://kaisou048.jp/

- Michiyo Noda was awarded the Okamura Prize, a special prize from the Japanese Society of Phycology, on March 17, 2021.