Ocean Newsletter

No.42 May 5, 2002

-

Resumption of Whaling and the Principle of Sustainable Use

Joji MORISHITA Head of Whaling Section, Far Seas Fisheries Division Fisheries Agency / Selected Papers No.4(p.10)

Japan aims for sustainable utilization under proper management of an abundant whale resource in future years. This has already been possible scientifically and legally. Anti-whaling protests don't provide reasonable grounds that contradict sustainable whaling.

Selected Papers No.4(p.10) -

Commercial Whaling is not for Sustainable Use

Greenpeace Japan

No matter how much the commercial whaling supporters say that they will not allow over-exploitation of whales, it doesn't provide any guarantee of full compliance in face of worldwide resurgence of commercial whaling. Commercial and industrialized whaling is never ever sustainable. Greenpeace is opposed to commercial whaling.

-

Detailed Report on the Mass Stranding of Sperm Whales

Toshio MURATA Oura Municipal Government, Kagoshima Prefecture / Selected Papers No.4(p.12)

Fourteen whales, thirteen of which died, were stranded on the shores of Oura, Kagoshima last January. Along with the difficulty, which was beyond imagination, of just moving each whale whose bulk was more than 20 tons, the town went through an awful lot of trouble, as if it were struck by a natural calamity.

Selected Papers No.4(p.12)

Resumption of Whaling and the Principle of Sustainable Use

Japan aims for sustainable utilization under proper management of an abundant whale resource in future years. This has already been possible scientifically and legally. Anti-whaling protests don't provide reasonable grounds that contradict sustainable whaling.

Grounds for sustainable whaling

One thing must first be made clear about the discussion on whaling: the Government of Japan aims at the sustainable use of only abundant species of whales, such as minke whale, while protecting depleted whale species consistent with international law including the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW). People who are against whaling claim that whaling in the past depleted whale resources and therefore sustainable whaling is impossible in the future. The fact is that whale resources were overexploited in the past by whaling for whale oil which was used for industrial purposes. In that sense, whaling for food has become a victim of the past overexploitation. It must be recognized that whaling for whale oil exploited far greater number of whales than whaling for food. Because the current demand for whales as food is far smaller than the past demand for whale oil, it can be easily imagined that the overexploitation experienced in the past will not happen again.

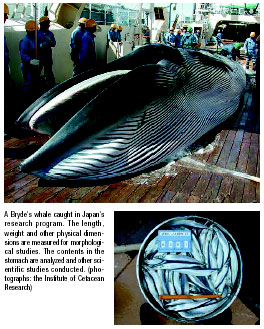

It must also be pointed out that with greatly advanced scientific knowledge about whales and wildlife management and new technologies available today, sustainable whaling is possible. Whaling was conducted in the past with insufficient knowledge and without using the technologies that we have today: a scientific and risk-averse method for calculating catch quotas that specifically accounts for uncertainty to ensure that utilization of abundant whale resources can occur without depletion, a device for monitoring positions and movements of whaling vessels with satellite technology, and a technique for identifying each individual whale based on DNA analysis to ensure that management rules are followed.

Scientific calculations of the number of whales show that the populations of minke whale and many other species of whales are abundant enough to allow managed and limited harvests based on safe catch quotas. This is not just the view of Japanese scientists but the agreed results of the cetacean scientists of the world at the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission (IWC). Many species of whales breed at annual rates of 3% to 7%. Most scientists in the world accept as common sense that if a conservative number of whales, e.g. 1% of the whale population, is to be caught, there will be no detrimental effects on the whale resource.

Furthermore, in 1994 the IWC completed and adopted a system called the Revised Management Procedure (RMP) which is a method of calculating catch quotas while ensuring whale resources are not depleted. The principle and logic of this method is simple. Compare whale resources to a bank account. Whale resources are the amount of deposited money. Like the deposited money in a bank which produces interest, whales breed and increase at a certain rate. When a catch quota is established within this "rate of interest", whale resources (the principal sum of the bank account) will never decrease. In practice, various additional safety factors are incorporated into the method to ensure the conservation of whale resources with a sufficient margin of safety. In addition to this, various measures will ensure catch quotas and other management decisions are strictly adhered to, i.e., introduction of a control and surveillance system that includes the placement of national inspectors and international observers to prevent over-harvesting and poaching. Compared to the surveillance systems of other fishery management and wildlife conservation organizations, the system agreed by the IWC to date is very effective. In other words, a scientific and regulatory mechanism for achieving sustainable whaling is already in place under the framework of the IWC.

Then what prevents the resumption of sustainable whaling?

As explained above, science and international laws and regulations are no longer a hindrance to the resumption of sustainable whaling. The major obstacles are now politics, cultures and values or ethics. For example, Australia, which is the strongest anti-whaling nation in the IWC, maintains a basic policy to object to resumption of commercial whaling under any conditions whatsoever even if whales are abundant and refuses to participate in any discussions which might lead to the resumption of whaling. This stubborn anti-whaling policy is based on their belief that whales are very special animals and harvesting them is against their ethics. On the other hand, millions of kangaroos are killed every year in Australia (the kangaroo catch quota in 2002 was 6.9 million), and the business for processing and selling their skin and meat is a major industry in Australia. The logic that catching whales is unethical, but catching kangaroos is ethical is unconvincing as long as the harvest is sustainable.

People have a very different set of values concerning various animals and human food depending on their cultures. For instance, cows are considered sacred animals in India. Would we accept it if India launched a world-wide anti-beef-eating campaign by claiming that cattle must not be eaten under any conditions? Undoubtedly not, yet that is exactly the approach to the whaling issue taken by the U.S., Britain, Australia, New Zealand and others, sometimes even with a threat of economic sanctions.

For anti-whaling governments, whaling is an issue that they can use to gain political advantage in environmental problems at no cost: politicians from anti-whaling nations can enhance their image as being environmentally-conscious by simply standing on the anti-whaling side because they do not have people concerned with whaling in their constituency. For politicians or governments that are criticized for lack of action in the area of global warming and other environmental problems, the whaling issue presents a good chance to improve their political standing.

Opinions have been expressed that because food is in oversupply in Japan, we do not need whale meat or, because we rarely eat whale meat, eating whale is no longer part of our culture and therefore we do not need to insist on the resumption of whaling to the point of making an enemy of the U.S. I will have something to say on other occasions about the present situation in which Japan is seemingly in a satiated state due to huge quantities of imported foodstuffs while the truth is that its food self-sufficiency rate is less than 40%. However, focusing back on the whaling issue, I simply object to those who would impose their opinion that whale meat is unnecessary on others. Although there are people who consider whale meat unnecessary, there are other people who consider whaling and whale meat definitely necessary. As stated above, the resumption of sustainable whaling to satisfy the wishes of those people who need whaling and whale meat is justified scientifically and legally. Is it appropriate to deprive such wishes by conceding to the objection of a powerful nation such as the U.S. made on the grounds of their ethics or values? If Japanese diplomacy is incapable of maintaining a policy that is supported by sound science and international laws, what is the point of that diplomacy? Even though most Japanese people do not wear Japanese kimono or go to watch Noh plays every day, they are undoubtedly part of Japanese culture. The contention that whale meat eating is not a part of Japanese culture since not all Japanese people eat the meat in everyday life, therefore, does not stand.

I have a strong objection to references to the whaling issue as an environmental issue and the anti-whaling campaign as an environmental protection movement. Whaling is a resource management issue and the scientific and legal issues concerning the management and sustainable use of whale resources have been solved and are no longer the obstacles for the resumption of sustainable whaling. The true focus of the whaling issue is now on the politics and the emotional conflicts arising from differences in ethics.

- Websites that provide more information:

The Whaling Section of the Fisheries Agency - http://www.jfa.maff.go.jp/j/whale/

The Institute of Cetacean Research - http://www.icrwhale.org

The Whale portal site - http://www.e-kujira.or.jp/