Ocean Newsletter

No.371 January 20, 2016

-

Continually Expanding Pacific Island, Nishinoshima ~volcano observations in sea areas by Japan Coast Guard~

Shigeru KASUGA Director General, Hydrographic and Oceanographic Department, Japan Coast GuardTaisei MORISHITA Director for Earthquake Research, Hydrographic and Oceanographic Department, Japan Coast Guard / Selected Papers No.21(p.4)

Since the eruption of Nishinoshima volcano and a resultant newborn island in the Ogasawara Islands was confirmed on November 20, 2013, the effusive outflow of lava over two years has greatly increased the size of the island. A bathymetric survey around the island carried out by the Japan Coast Guard in the summer of 2015 revealed that this eruption of Nishinoshima volcano was one of the largest domestic eruptions in terms of expelled volcanic material since the end of World War II. As the broad extent of Japan's jurisdictional waters is dependent on volcanic islands, observation activities are important not only for the safety of residents and navigation, but also from the perspective of the delimitation of Japan's jurisdictional waters.

Selected Papers No.21(p.4) -

Using Big Data from Ships ~introducing activities of the Smart Navigation System Research Group~

Hiroshi MORONO Senior Advisor, Terasaki Electric Co., Ltd.

The main objectives of the Japan Ship Machinery & Equipment Association's Smart Navigation System Research Group are to develop technologies for the Internet of Things (IoT) as a base for making use of big data accumulated by machines and equipment installed on ships, as well as to promote the international standardization of such technologies. This article explains the usage of big data made possible by the application of IoT.

-

Vilhjalmur Stefansson and the Arctic

Kristin NEWTON Glass Artist

Only 100 years ago, oceans were still a mystery, vast and unexplored. The Arctic and Antarctica were challenges that explorers were determined to conquer. Vilhjalmur Stefansson went on three expeditions to the Alaskan and Canadian Arctic between 1906 and 1918, making many discoveries along the way. Having narrowly escaped death on several occasions, he believed that, in order to survive in extreme environments "Good health and bodily strength, while desirable, are secondary. The chief thing is mental attitude."

Vilhjalmur Stefansson and the Arctic

Before the age of the airplane, people had a much more intimate relationship with the sea, as travel by sea took weeks, months, and sometimes years. Imagine seeing nothing but ocean for weeks at a time. Now, however, ships that ply the ocean report seeing islands of trash and almost endless pollution. Oil spills wipe out sea life and coastlines for years. Only 100 years ago, oceans were still a mystery, vast and unexplored. The Arctic and Antarctica were challenges that explorers were determined to conquer. The Arctic was considered an inaccessible wilderness. With the exception of a few, many courageous explorers were stranded for months, sometimes years, or ended their journey tragically. Travel was slow and dangerous. The Inuits had thrived in this environment for thousands of years, but for the white man it was alien territory.

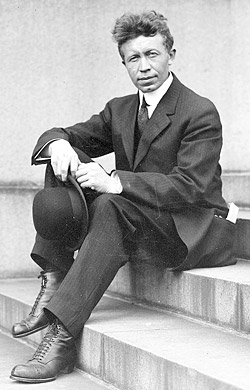

The Arctic has always been alive, teeming with people and animals, with culture and traditions, whereas Antarctica is less livable, except for penguins and a few other hearty sea creatures. Western societies tended to think of both the North Pole and South Pole as bleak, white, frozen wastelands until explorers began to penetrate the vast interiors. One such explorer was my Icelandic grandmother's cousin, Vilhjalmur Stefansson, anthropologist and explorer (1879-1962). Between 1906 and 1918, he went on three expeditions to the Alaskan and Canadian Arctic, each trip lasting between sixteen months and five years. Stefansson's discoveries included the edge of the continental shelf, as well as a number of uninhabited islands in the Canadian Arctic.

Vilhjalmur and my grandmother, Gudrun, came from a long line of Icelandic Vikings. Vikings had lived on the sea and explored the world, discovering America hundreds of years before Columbus. It's in their DNA!

In the late 1800s Iceland was an impoverished, wretched country, not the popular tourist spot it is now. My grandmother had escaped Iceland when she was young, and lived in Paris and Copenhagen, until circumstances forced her to move back to Iceland.

My father was born in 1920 on the family sheep farm, a sod house in Skagafjordur, not far from the Arctic Circle. When he was 5, he rode his horse one full day to the nearest doctor to get his tonsils taken out, then rode another full day back to the dark sod house. He never saw a car until he was 12 years old. Many people had tuberculosis in those days and he spent some of his childhood in a tuberculosis hospital.

Some of the relatives who lived on the family farm left Iceland to move to Canada in 1877 during a wave of emigration. The journey took seven weeks. Life wasn't any better in this promised land and many people starved the first year. Vilhjalmur Stefansson was born in Arnes, Manitoba in 1879, but after two of his siblings died from the extreme conditions his parents moved the family to rugged North Dakota. Later he thanked this austere upbringing for his toughness and ability to survive under very harsh conditions.

■Vilhjalmur Stefansson

■Vilhjalmur Stefansson

(1879-1962)

Stefansson was an anthropologist and learned the languages of the Inuit, therefore he learned much more than others who merely asked questions. He lived for a number of years with the Inuit, learning their way of life. He was accepted as a member of the family and learned the culture as a child learns. This was a great advantage and stood him in good stead many, many times.

He said the Inuit had preconceived ideas about what the white man wanted and as a result would give answers to satisfy those preconceptions, whether they were true or not. Anthropologists worldwide have gradually come to the same conclusions, not only about the people they question, but also about the anthropologists' own preconceived ideas when they formulate their questions.

Vilhjalmur was a keen observer and voluminous writer, although he was negligible with scientific reports, much to his sponsors' chagrin. He observed the careless forest fires, burning acres in the Canadian wilderness, many caused intentionally and ignored by the Rangers. He observed the habitual cruelty of white men to the dogs - starving them, and killing or maiming them for entertainment. He observed the effect of the missionaries on the Indians and Inuits, which led to the rapid loss of their lifestyle and ancient traditions.

First the traders, then the whaling ships, brought things the Inuit had never seen. These goods were first considered luxuries but soon became a necessary part of life. From 1889 to 1906 the Inuit's lifestyle changed completely, from an independent self-sufficient people to a manipulated dependence on "civilized goods," such as sugar, flour, canned food, not to mention a Christian mindset. When he was with the Inuit in 1907, they had not yet been Christianized. But when he returned in the summer of 1908, they had all been converted. This resulted in acting against common sense, such as not doing anything on the Sabbath for fear they would go to hell. Such is brainwashing.

During the summer of 1908, only one whaling ship managed to make it through the ice. The ice floes, instead of moving parallel to the coast, jammed up against it because of a change in the winds. The Inuit, who had become used to imported luxuries, felt deprived and were on the verge of starvation, forgetting that their ancestors had survived for thousands of years on caribou and fish. Stefansson made many observations on the relationship between health and diet, and wrote several books on the topic.

On that trip, Stefansson had been intending to live off the land, but realized that, where there had been thousands of caribou ten years before, now there were very few; they had been wiped out like the buffalo in America. In America, the buffalo inhabited land needed for farming, but that wasn't the case in Canada or Alaska. They were simply slaughtered for mindless entertainment.

Stefansson often said the word "adventure" meant mishaps and trouble. The best exploration, he said, was a boring one, based on "better safe than sorry." Even one small miscalculation in the Arctic could mean death, and he had several close calls. A number of his associates died under these trying conditions. He strongly believed that by adapting to Inuit ways, Arctic explorers could live on the land, even on the ice floes, as he had learned to do. In order to prove this was possible, Stefansson and two companions traveled across the moving ice for 800 kilometers from the Beaufort Sea to Banks Island. From April 1914 to June 1915 he lived on the ice packs. He said, "Good health and bodily strength, while desirable, are secondary. The chief thing is mental attitude."

From 1913 to 1916 Stefansson organized the Canadian Arctic Expedition to search for undiscovered land masses and to carry out through-ice depth soundings to map the edge of the continental shelf. It's a very long story, full of many troubles and hardships. In the end, one ship was crushed by the ice and out of 25 crew and expedition members, 11 died. This disaster clouded his reputation for years. After a serious illness in 1918, Stefansson left the Arctic forever.

However, Vilhjalmur Stefansson had a rich, full life after the Arctic. As a famous explorer, he gave lectures, wrote 24 books, including his autobiography, and more than 400 articles on his travels and observations. He became Director of Polar Studies at Dartmouth College and his personal papers and collection of Arctic artifacts are available to the public at the Dartmouth College Library.

The saddest thing I've noticed as I read his accounts of his travels, is that the abuse of nature which began with the explorers has increased dramatically with each passing year. Soon Shell Oil will destroy the pristine Alaskan sea solely for the sake of profits.