Ocean Newsletter

No.15 March 20, 2001

-

Toward Elimination of Substandard Shipping

Moritaka HAYASHI Professor, Waseda University School of Law

Ships that are below internationally accepted standards as well as substandard operators and flag States can cause serious harm to human life, the marine environment and the industry. Increasingly stronger steps are being taken to eliminate such ships particularly by major maritime countries in Europe and North America, and the EU. Can Japan, with 90% of its commercial fleet under open registries, remain unaffected, without any action?

-

Japan's Port and Shipping Also Require Bold Policy Action

Shinichiro TANAKA Director, Ship Machinery Division,Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), Singapore Selected Papers No.1(p.12)

Singapore, a country making the most of its huge hub port and still continuing its rapid economic growth. Learning from Singapore's success, Japan needs to rethink its priorities and create bold policy to revitalize its ports and shipping.

Selected Papers No.1(p.12) -

Seishi, Blowfish and the Japan Sea

Akio KOU President, Yusui Company

Japan and Korea are very close, yet far apart, separated by the Japanese Sea that lies between them. The culture of appreciating blowfish, common to both countries but with different cooking and presentation styles, symbolizes the delicate relationship between the Japanese and Koreans. This relationship has been fermented by a history of human and cultural exchanges, many of which are very unhappy memories for the Korean people. The Sea of Japan has been the center stage through these exchanges, but despite the hard times that have existed between the two countries in the past, it shouldn't be understood as the sea that separates them, but as the sea that has linked, is linking and will link the two countries into the future.

Japan's Port and Shipping Also Require Bold Policy Action

Singapore, a country making the most of its huge hub port and still continuing its rapid economic growth. Learning from Singapore's success, Japan needs to rethink its priorities and create bold policy to revitalize its ports and shipping.

Free trade and attracting foreign investment

Of all the nations of Southeast Asia, Singapore, which has only been independent for 35 years, has achieved the most stunning economic growth. How has this tiny citystate accomplished such an extraordinary feat?

Simply put, with few natural resources and about the same land area as Awajishima, Singapore's only resource is her people. Its most talented people are concentrated in the government, which guides effective policy implementation.

With a stable, powerful government, Singapore is able to promote trade liberalization, offer incentives to attract foreign enterprise and personnel, make English its official language and offer ports, airports, industrial zones and other infrastructure that is second to none in the world. Singapore's greatest engine of growth is her civil service, which tables and implements a steady stream of policies aimed at boosting the competitive position of the nation's economy.

Singapore is all but devoid of primary industries such as agriculture, fishing, forestry and mining. All foodstuffs are imported and a pipeline from Malaysia supplies almost all of the water her life depends on. If Singapore's supplies from neighboring states were cut off, its economy would be strangled in a heartbeat.Singapore is therefore constantly dependent on the bold policymaking of its leaders. The first phase of Singapore's strategy was to leverage its favorable geographic location as a transit port and become a free-trade zone with no tariffs. Its greatest policy for economic growth was to focus on attracting foreign investment-in sharp contrast with Japan, which nurtured and protected its domestic industries. Singapore recognized that, as a nation with no resources, a small labor pool and a tiny market, it was in no position to favor domestic industries. Through a wide range of measures from infrastructure development to tax and other incentives, Singapore created an environment that facilitated the entry of foreign enterprise.

Enhancing the function of port facilities

Singapore's greatest infrastructural asset is her port. Setting its sights on a leading role as a shipping hub, Singapore built up its port infrastructure and was quick to introduce computer systems to simplify port entry and exit procedures. In 1972 Singapore became the first country in Southeast Asia to implement container-handling facilities. The country is constantly improving its port services, acquiring tugboats, enhancing fueling and provisioning facilities, offering better support services and enabling 24-hour port operation. As a result of these efforts, 80% of the container cargo Singapore handles consists of transshipments to and from neighboring countries.

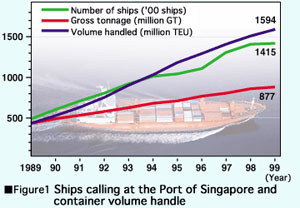

The Port of Singapore links 320 shipping companies and 738 ports around the world. In 1999, a total of 141,523 ships called at the port, which handled 877,130,000t of cargo that year (see Figure 1) the world's largest volume for the 14th year in a row.

Container cargo totaled 15,940,000TEU (a unit equivalent to a 20-foot container) in 1999, making Singapore the world's second largest container port by volume (only slightly behind the No. 1 container port, Hong Kong). Singapore became the world's leading container port for the first time in 1990, when it handled a container cargo volume of 5,220,000TEU, a figure that has tripled in the intervening years.

Of the world's top 10 ports, five (Hong Kong, Singapore, Kaohsiung, Busan and Shanghai) are in Asia. At one time Japan's ports ranked among this number; today Japan's ports handle only a sixth or a seventh of the volume that Singapore does (see Table 1).

In October 2000, in connection with a free trade agreement (FTA) signed between Japan and Singapore, the Port of Singapore welcomed Takeo Hiranuma, Japan's Minister of International Trade and Industry. Profoundly impressed by the port's computerized customs clearance system and its smooth container traffic, Mr. Hiranuma was reported in Japanese newspapers to have remarked, "it's like watching a video game! With the new free trade pact with Singapore,if Japan fails to implement advanced IT systems as Singapore has, our nation will be unable to compete."

Increasing number of ships registered in Singapore

In its bid to emerge as a distribution hub for Southeast Asia, Singapore not only enhanced its port facilities but also worked hard to increase the number of ships registered there. These efforts were highly successful: the number of commercial shipowners registered grew from 712, with total tonnage of 7,270,000t, in 1989 to 1,736m, with total tonnage of 21,780,000, in 1999. Today Singapore has grown to become the world's 7th largest maritime shipping nation (see Table 2).

According to the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA), 3,360 ships with a total gross tonnage of 23,750,000GT are registered in Singapore as of the end of 1999. After the number of Singapore-registered ships passed the 10 million-GT mark in 1992, the figure grew at a rate of about a million GT per year for several years. In 1996 this growth accelerated sharply, so that Singapore reached its target of "20 million GT by 2000" far ahead of schedule, in October 1997. This impressive growth continues to this day, with the gross tonnage of registered ships surpassing 22 million GT in 1998 and 23 million GT in 1999.

The engine driving this brisk expansion in ship registration is a scheme called the Approved International Shipping Enterprise (AIS), introduced in 1991. Under this scheme, companies approved under AIS and registering at least 10% of their fleet in Singapore can obtain an exemption from taxes on their ships not registered in Singapore. The scheme also makes hiring crews easy, with no restrictions on the citizenship of crewmembers. These enticements are compelling reasons for shipowners to register their vessels in Singapore.

Studying Singapore's economic growth strategy

JETRO often receives visits on "port sales" missions from managers of various and sundry ports, both prefectural and municipal, from every region of Japan. This helter-skelter approach seems an odd way to run a country's ports. Whatever the merits of devolving powers to the regions, such lack of coordination is surely in appropriate for the management of Japan's ports as they fight to attract business. Few of Japan's ports offer full service on a 24-hour basis. If Japan does not form a coherent vision for her ports, from the standpoint of a more unified, national perspective, the nation will become lost in the global competition for shipping business. Japan's merchant fleet of Japanregistered vessels will slip beneath a wave of competition from better-managed ports.

Lee Kwan Yew, Singapore's founder and Elder Statesman, has noted that Singapore was profoundly influenced by the example of the miraculous recovery and expansion of Japanese industry after World War II. Today, says Mr.Lee, Japan's real problem is not the economy, but policy

| FY 1989 | FY 1999 | |||||

| Rank | Port | '0,000 TEU | Rank | Port | '0,000 TEU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hong Kong | 446 | 1 | Hong Kong | 1,610 | |

| 2 | Singapore | 436 | 2 | Singapore | 1,594 | |

| 3 | Rotterdam, Holland | 360 | 3 | Kaohsiung | 669 | |

| 4 | Kaohsiung | 338 | 4 | Busan | 644 | |

| 5 | Kobe | 246 | 5 | Rotterdam | 640 | |

| 6 | Busan | 216 | 6 | Long Beach | 441 | |

| 7 | Los Angeles | 206 | 7 | Shanghai | 421 | |

| 8 | New York/New Jersey | 199 | 8 | Los Angeles | 383 | |

| 9 | Jilong | 179 | 9 | Hamburg | 375 | |

| 10 | Hamburg | 173 | 10 | Antwerp | 361 | |

| 11 | Long Beach | 155 | 13 | Tokyo | 270 | |

| 12 | Yokohama | 151 | 17 | Yokohama | 220 | |

| 16 | Tokyo | 144 | 17 | Kobe | 220 | |

Table 2 World rankings in size of merchant fleet (country of registration) in 1989 and 1999

| FY 1989 | FY 1999 | |||||

| Rank | Country | Gross tonnage ('0,000t) | Rank | Country | Gross tonnage ('0,000t) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Liberia | 4,789 | 1 | Panama | 10,525 | |

| 2 | Panama | 4,736 | 2 | Liberia | 5,411 | |

| 3 | Japan | 2,803 | 3 | Bahamas | 2,948 | |

| 4 | Greece | 2,132 | 4 | Malta | 2,821 | |

| 5 | Cyprus | 1,813 | 5 | Greece | 2,483 | |

| 6 | Norway | 1,559 | 6 | Cyprus | 2,364 | |

| 7 | China | 1,351 | 7 | Singapore | 2,178 | |

| 8 | Bahamas | 1,157 | 8 | Norway | 1,980 | |

| 9 | Singapore | 727 | 9 | Japan | 1,706 | |

| 10 | Malta | 322 | 10 | China | 1,631 | |