1. Introduction

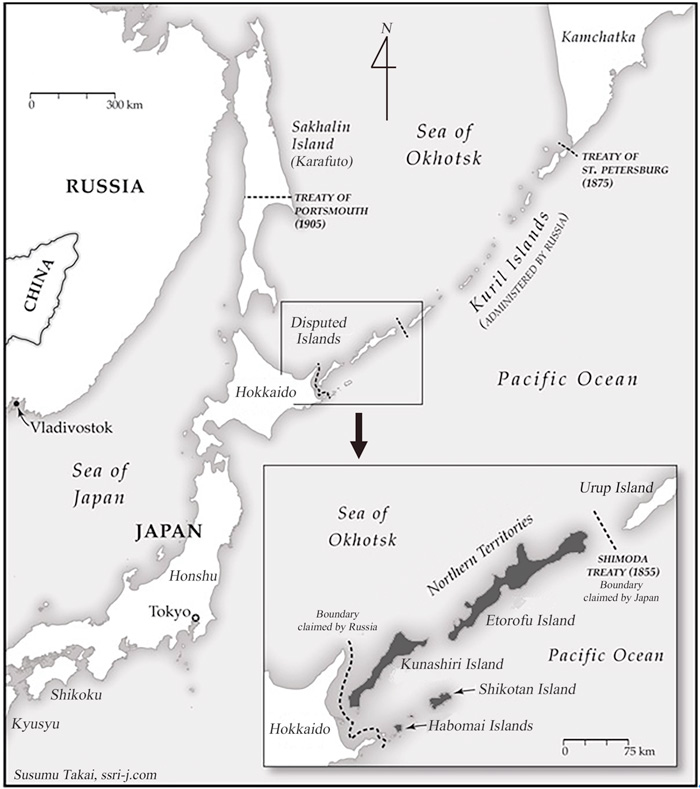

Japan's territorial dispute with Russia[1] has drug on since the end of World War II. Specifically, the point of contention is over whether Japan's renunciation of its rights to the Kurile Islands specified in Article 2, section (c) of the San Francisco Peace Treaty (SFPT) includes Etorofu Island, the Habomai Islands, Kunashiri Island, and Shikotan Island. The Soviet Union (also referred to as the USSR) in the decades following WWII steadily asserted that the issue had been resolved and stuck by its claim to the four islands, known as the Southern Kurile Islands by Russia and the Northern Territories by Japan. Likewise, Japan has remained firm in asserting that it was not required under the SFPT to renounce its sovereign rights to the islands as they had never been the territory of other foreign state. The failure of Japan and the USSR to sign a peace treaty after the war assured the four northern islands (hoppo yonto)[2] has remained a sticking point in Japan-Russia relations.

The issue of the Northern Territories is largely one of interpretation. It stems in large part to a lack of consensus between Japan and Russia over the wording and legitimacy of views presented in the wide-ranging international agreements and declarations composed during and in the wake of WWII, when Japan's renunciation of territory was a subject of much debate.

The USSR claimed from early on that the issue had been resolved, citing documents such as the Cairo and Potsdam Declarations, the Yalta Agreement, Japan's declaration of surrender, the Supreme Command for the Allied Powers' General Order Number I, and the SFPT as evidence. For example, in 1961 Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev explained in a letter to Japanese Prime Minister Ikeda Hayato[3] that

the Potsdam Declaration in setting the terms of Japan's surrender limited Japanese sovereignty to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku, and other minor islands, and by signing the articles of surrender the Japanese government pledged to faithfully implement the terms of the Declaration. The Kurile Islands were excluded from territory remaining under Japanese control and the Japanese government's insistence on their return violates this earlier agreement. . .

The Yalta agreement clearly states that South Sakhalin and the Kurile Islands shall be handed over to the Soviet Union without condition or reservation. . .

The Yalta agreement, General Order Number I, and the San Francisco Peace Treaty do not divide the Kurile Islands, but consider the chain in its entirety. The leaders of the US and USSR have traded letters affirming this point. As it were, there is no base for Japan's attempted claim that these international documents specify the return of only a few islands to the USSR and not the entire Kurile Island chain.

In its rebuttal Japan argued that Etorofu Island, the Habomai Islands, Kunashiri Island, and Shikotan Island were Japanese sovereign territory[4] by saying that

the Japanese government renounced all right, title, and claim to the Kurile Islands in the San Francisco Peace Treaty, however, this did not include the Habomai Islands and Shikotan Island, which the Soviet Union has agreed upon concluding a bilateral peace treaty to return to Japan, or Etorofu Island and Kunashiri Island as they are from a historic and legal stand point clearly Japanese territory.

In addition, the Allied Powers avowed they would not seek territorial expansion as they dealt with the aftermath of World War II, affirming this as a principle in the Atlantic Charter and Cairo Declaration. This principle also served as a core element of the Potsdam Declaration, which the Soviet Union acceded to, and the San Francisco Peace Treaty. In light of this, there is no reason that Japan under the treaty should lose sovereign territory never claimed by any other foreign state.

At the time, Japan and the Soviet Union were at loggerheads as to whether Etorofu Island and Kunashiri Island were to be included along with the Habomai Islands and Shikotan Island in Japanese renunciation of its claim to the Kurile Islands, as required under the SFPT. As I mentioned earlier, the issue came down to interpretation of the various international treaties and declarations. Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin was involved in the drafting of many of these documents, and it is not insignificant that he made a clear geographic distinction when talking about the "Kurile Islands" and "all the Kurile Islands." In this article I will reexamine these international agreements, which both Japan and the Soviet Union have used to support their territorial claims, under the premise that the issue of the Northern Territories stems from what Stalin's assumed view of the geographic boundaries of the Kurile Islands.

2. Geographic Boundaries of the Four Northern Islands

To come to grips with the issue of the four northern islands requires understanding how the geographic boundaries of the Northern Territories were defined in different international documents. Specifically with regard to disputes over documents where no clear definition for the territories is provided, deciding on the most appropriate interpretation requires close consideration of how drafters understood the terms they used.

In broad terms the Northern Territories encompass the southern section of Karafuto (Sakhalin) below latitude 50°N and its adjacent islands, the Kurile chain,[5]the Habomai Islands, and Shikotan Island. Japan and Russia for many years jointly controlled Karafuto, and the Treaty of Shimoda[6] in 1855 preserved this borderless arrangement in specifying that the island "remains unpartitioned." However, persistent conflict between Japanese and Russian inhabitants along with other issues led the two nations to sign the Treaty of St. Petersburg[7] in 1875 whereby Russia ceded the Kurile Islands from Uruppu Island northward to Japan in exchange for the entirety of Karafuto. Following the Russo-Japanese War, however, the two nations signed the Treaty of Portsmouth[8] in 1905 that ceded the southern section of Karafuto below the fiftieth parallel to Japan. In 1951, Japan renounced its claim to this portion of the island,which it called South Karafuto, under the San Francisco Peace Treaty.[9]

The Treaty of Shimoda, the first commerce and navigation treaty defining the borders between Japan and Russia, established that the "whole island of Uruppu, and the Kurile Islands to the north of the island" were possessions of Russia and that the islands south of Etorofu Island belonged to Japan. With the signing of the Treaty of St. Petersburg in 1875 Russia gained sovereignty over the entirety of Karafuto, and in return the Russian Tsar ceded the 18 "Kurile Islands" to Japan. This illustrates that Japan came by Etorofu Island, Kunashiri Island, and the Kurile Island chain through peaceful means. It also provides evidence that the islands were considered sovereign Japanese territory until Japan relinquished rights to the Kurile Islands as a condition of the SFPT. It is important to bear in mind, however, that while the 18 islands north of Uruppu Island had at one time been Russian territory, Etorofu Island and Kunashiri Island[10] remain Japanese territory, having never been claimed by any other state. This fact remains a core point in Japan's claim that the two islands are not part of the Kurile Island chain, and thus not subject to repossession by Russia under the SFPT.

In terms of marine geology, the Habomai Islands and Shikotan Island are part of Hokkaido, making them Japanese territory. However, in the final days of WWII the Soviet Union occupied both islands along with the southern portion of Karafuto and the entire Kurile chain, a situation that continues under the present Russian government. Paragraph 9 of the 1956 Joint Declaration of Japan and the USSR[11] calls for "actual handing over" of the islands to Japan by the Soviet Union following the conclusion of a peace treaty. However, no peace agreement was ever reached. After Japan signed the 1960 Security Treaty with the United States the USSR left the negotiating table, saying it would not hand over the islands unless the United States withdrew its troops from Japan.

3. The Cairo Declaration and Yalta Agreement

A. The Cairo Declaration

As World War II raged in Europe, the Axis Powers[12] led by Germany on June 22, 1941 turned its military might against the Soviet Union. Japan, siding with Germany, entered the conflict against the Allied Powers[13] led by Britain and the United States on December 8, 1941 (Japan time). However, Japan and Russia agreed to a non-aggression pact[14] on April 13, 1941 and remained at peace for a majority of the war.

As momentum shifted in favor of the United States after nearly two years of fighting, American, British, and Chinese leaders met in Cairo, Egypt, to reaffirm their intent to defeat Japan and to discuss the shape of postwar Asia. Released on December 1, 1943, the Cairo Declaration states that Britain, China,[15]and the United States "covet no gain for themselves and have no intension of territorial expansion" in stripping Japan of all the territory it had taken through violence and greed.

The declaration reaffirmed the commitment extolled by the Allies in the earlier Atlantic Charter to not seize territory. US President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill drafted the Atlantic Charter during the first years of the war in Europe, signing it on August 14, 1941. The first clause of the document establishes that the two "countries seek no aggrandizement, territorial or other," and the second clause states they "desire to see no territorial changes that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned."

It is true the Soviet Union was not involved in drafting the Cairo Declaration, and thus did not join America, Britain, and China in renouncing territorial expansion. However, it is bound by the principles of the document as a signatory of the Potsdam Declaration, which in Article 8 states that "the terms of the Cairo Declaration shall be carried out." It can be said then, that the USSR in joining the Allies to establish a new postwar order pledged to not seek territorial gain.

B. The Yalta Agreement

As Germany stood on the brink of defeat in 1945, Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin met in Yalta on the Crimean Peninsula on February 4-11, to discuss the shape of postwar Europe along with the conditions for the Soviet Union to join the Allied Forces in the war against Japan. The conference produced the Yalta Agreement. In reference to Japan, the second clause of the agreement states that "the former rights of Russia violated by the treacherous attack of Japan in 1904 shall be restored." According to sub-clause (a) of the document this meant that "the southern part of Sakhalin as well as the islands adjacent to it shall be returned to the Soviet Union." The third clause then goes on to specify that "the Kurile Islands shall be handed over to the Soviet Union."

Many in the United States disputed the validity of the Yalta Agreement, pointing to such factors as the style, content, language, and even the timing of the document.[16] Despite these criticisms, it should remain, at the very least, a binding agreement among Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin. However, the US State Department later sent a memorandum to the Japanese government saying it considered the Yalta Agreement to simply be a statement of common purposes by the then heads of state and not a final determination, adding that it had no legal effect in transferring territories.[17]

It should be noted, however, that while the Yalta Agreement states that the southern part of Sakhalin (Karafuto) "shall be returned," it specifically asserts that the Kurile Islands "shall be handed over." This variance in phrasing reflects the historically different backgrounds of the two territories. As I discussed above, Japan acquired South Karafuto under the Portsmouth Peace Treaty following the conclusion of the Russo-Japanese War. Having been gained in wartime, the Yalta Agreement dictates that it was to be "returned" to the Soviet Union. In contrast, Japan did acquire the Kurile Islands through violence and greed, and as the island chain had once been the sovereign territory of the USSR, it was to be "handed over."

Stalin in a meeting with US presidential envoy Averell Harriman on December 15, 1944, hinted that the "entire" Kurile arc had at one time been a part of Russia, and openly said later that he thought all the Kuril Islands should be "returned" to the USSR.[18]This suggests that even prior to the Yalta Conference, Stalin considered Etorofu Island and Kunashiri Island to be included in Russia's claim to the entire Kurile chain. In 1917, Vladimir Lenin in his famous Decree on Peace,[19] which he put forward near the end of World War I, called for a just or democratic peace without annexations and without indemnities. It remains unclear, however, if Stalin took these principles to heart when representing the Soviet Union at Yalta.

Professor John J. Stephan describes the exchange of opinions between Roosevelt and Stalin at the Yalta Conference in the following manner.[20]

Roosevelt "disposed of the Kurils with breathtaking dispatch. A few minutes of amiable exchanges with Stalin at a closed meeting on 8 February (3:30 to 3:45 p.m.) sufficed to conclude the territorial transfer. Stalin opened by lumping together the Kurils and southern Sakhalin, saying: 'I only want to have returned to Russia what the Japanese have taken from my country.'"

Roosevelt joined the Yalta Conference under the false impression that Japan had wrenched the Kurile Islands from Russia in 1905 by violence and greed, and he likely felt that the entire arc should be restored as per the principles of territorial alienation enunciated in the Cairo Declaration.[21] Stalin, however, was apparently unaware of the US president's misinterpretation, and instead expected Churchill and Roosevelt, who had pledged to not seek territorial expansion, to be adverse to the "return" of the Kurile Islands north of Uruppu Island. It can be assumed then, that Stalin looked to strike a compromise by choosing the phrase "shall be handed over."

4. The Potsdam Declaration and General Order Number I

A. The Potsdam Declaration

The German government fell into turmoil following Adolf Hitler's suicide, eventually surrendering to the Allied Forces on May 8, 1945. The leaders of Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States met in Potsdam, Germany, from July 17 to August 2 to negotiate the terms of the end of the war. The conference produced the Potsdam Declaration,[22] which Prime Minister Churchill, Chairman of the Nationalist Government of China Chiang Kai-shek, and US President Harry Truman signed and released on July 26. Stalin, however, was still bound by the Japanese-Soviet Non-aggression Pact and did not endorse the document.

However, roughly three months after the Germany's surrender, Stalin, as agreed during the Yalta Conference, joined the Allied Forces in the war against Japan. Russia signed of the Declaration by the United Nations July 26.[23] Foreign Affairs Minister Vyacheslav Molotov on August 8 notified Japanese Ambassador to the Soviet Union Sato Naotake of this development along with the news that the USSR would join the war against Japan the following day. True to his word, Soviet forces commenced fighting on August 9. While it appears that the Japanese embassy in Moscow attempted to relay these messages[24] to leaders in Japan, they were not received. It was not until August10[25] that Soviet Ambassador to Japan Yakov Malik, a day after arranging a meeting, passed Japanese Foreign Minister Togo Shigenori the overdue declaration of war. This is not insignificant as it came four days after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on August 6 and one day after a second nuclear blast leveled Nagasaki.

As the end of the conflict neared, Britain, China, and the United States released a joint proclamation on July 26, often called the Potsdam Declaration after the city where it was drafted, providing Japan the opportunity the war to a close. With regard to territorial issues, Article 7 of the document called for the occupation of Japan to establish a new order in the wake of the war, while Article 8 stipulated that "the terms of the Cairo Declaration shall be carried out and Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku and such minor islands as we determine."

Japan is said to have ignored the Potsdam Declaration on account that it was waiting for a response from the Soviet Union, which it had requested to be a go-between in brokering peace. However, the Soviet army had already invaded Karafuto and northeast China by the time Ambassador Malik delivered the declaration of war on August 10. It was not until August 14 that Japan notified the Allied Forces through the Swiss government that it accepted the Potsdam Declaration. As I mentioned above, the declaration was an international agreement among the United States, Britain, China, and the Soviet Union, and by acceding to it the USSR was thereby bound to uphold the terms of the Cairo Declaration.

B. General Order Number I

Truman sent a draft of General Order Number I to Stalin on August 15 to lay the groundwork for Japan signing the declaration of surrender. Under the draft order, Japanese forces in Manchuria, Korea north of latitude 38°N, and Karafuto would surrender to the Commander-in-Chief of Soviet Forces in the Far East.[26] As this illustrates, Truman did not include the Kurile Islands in the original draft of the order. Stalin, however, responded the following day and asked it be amended to 1) include all the Kurile Islands in the region of surrender of Japanese forces to Soviet troops in accordance with the decision of the three powers in the Crimea that these would come into possession of the Soviet Union; 2) include the northern part of Hokkaido in the region of surrender of Japanese armed forces to Soviet troops; and 3) set the demarcation line between the northern and southern half of Hokkaido on the line leading from the city of Kushiro on the eastern coast to the city of Rumoi on the western coast and include the named cities in the northern half of the island.[27] In proposing the above alterations, Stalin specifies that all the Kurile Islands[28] were promised to the USSR under the Yalta Agreement.

Truman responded to Stalin's request to add all the Kurile Islands to the region of surrender on August 18, which was followed by subsequent back and forth between both sides. When Japan officially surrendered on September 2, the final version of the order included the island chain in the statement that Japanese forces in "Manchuria, Korea north of 38 degrees North latitude, Karafuto, and the Kurile Islands, shall surrender to the Commander-in-Chief of Soviet Forces in the Far East." It is essential to note that while the Kurile Islands were added, the reference to "all" the islands as per Stalin's proposed amendment was left out.

Stalin initiated the invasion of the Kurile Islands on August 18, the same day Truman sent his response, by attacking Japanese forces on Shumshu Island, the northernmost island of the Kurile chain. The assault continued until Japanese troops surrender on August 23. Soviet forces then moved southward along the chain occupying islands as far as Uruppu Island before heading north again.[29] It can be assumed that Stalin ordered the campaign with the full knowledge that General Order Number I would be amended to give the USSR responsibility for disarming Japanese forces on the Kurile Islands. The operation eventually encompassed all the Kurile Islands, the Habomai Islands, and Shikotan Island, but it is significant to note that Soviet troops initially halted their advance short of Etorofu Island before turning north. This fact strongly suggests that Stalin did not consider Etorofu and Kunashiri Islands as part of the Kurile chain.

5. Soviet Territorial Boundary

A. Nationalization of the Kurile Islands

Above, I touched on the exchanges between Stalin and Truman over the disarming of Japanese forces. In their back and forth, the two leaders heatedly discussed landing rights for US aircraft on one island in the central group of the Kurile Islands. Truman in a response to the Soviet leader on August 25 rejected Stalin's stance by emphasizing America's position that the Kurile Islands were not Soviet territory but part of Japan. He then went on to assert that any territorial change must be made at a peace settlement. Stalin eventually conceded to the US president's request for landing rights for the extent of the occupation of Japan.[30]

Even though Stalin was confident that the Soviet Union's claim to the Kurile Islands would be recognized under the Yalta Agreement once Japan surrender, he understood that peace treaties and other agreements forged in the postwar period would force Japan renounce its claims to the island chain. In other words, he knew that until a treaty stipulating the return of the Kurile Islands was ratified the island chain would remain Japanese sovereign territory. By extent, then, the Northern Territories in broad terms were not part of the area to be occupied by the Soviet Union following Japan's surrender. It can be said with confidence, then, that in the absence of exceptional circumstances, the USSR had no authority to act beyond the bounds of internationally recognized agreements shaping the postwar period.

Unwilling to leave it in the hands of the Allied Forces, the Soviet Union took a series of unilateral steps to incorporate the Kurile Islands and southern Karafuto into its territory. On February 2, 1946, the Soviet Union issued the Decree of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet on the Creation of the South-Sakhalin Province in the Khabarovsk Region that states as of September 20, 1945, all the land and natural resources, including forest and water, of southern Karafuto and the Kurile Islands belong to the Soviet people.[31]

The Soviet government then passed a second decree on January 2, 1947 that disbanded South-Sakhalin Oblast, removed it from the Khabarovsk Region, and incorporated it into Sakhalin Oblast.[32] However, an annotation in a 1975 collection of laws and decrees of the USSR spanning 1938-1975 shows that earlier records (Official Gazette of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet 1946 No.5) merely state that South-Sakhalin Oblast was created by decree (указ, ukase) on February 2, 1946, and provides no specification as to regional composition. The official Soviet newspaper Pravda on February 27, 1947 announced that Supreme Soviet had amended the Constitution so that effective of February 25 the Sakhalin Oblast was incorporated into Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), the largest republic of Soviet Union.[33] On April 18 the city of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk was made the capital of the Sakhalin Oblast.[34]

RSFSR in amending the Constitution of the Soviet Union on March 13, 1948, revised Article 14 of its Constitution to include Sakhalin along with Arkhangelsk, Astrakhan, Bryansk, and other outlying territories of Soviet Russia.[35] However, it is unclear if Etorofu Island, the Habomai Islands, Kunashiri Island, and Shikotan Island were included with the incorporation of the Sakhalin Oblast.

RSFSR's amendment drafting committee head Pyotr Bahmurov reported to government leaders that the amendment, following the Soviet army's liberation of southern Karafuto and the Kurile Islands, legally restores these areas as Russian territory in the Far East. He went on to say the act removes both southern Karafuto and the Kurile Islands from the Khabarovsk Region and incorporates these into Sakhalin Oblast.[36] The statement clearly shows that the Kurile Islands are considered part of Sakhalin Oblast, but whether the region also includes Etorofu and Kunashiri islands in the Kurile chain along with the Habomai Islands and Shikotan Island remains uncertain.

It can be inferred that Bahmurov in stating the Kurile Islands had been "restored" to RSFSR was referring the 18 islands north of Uruppu Island that Japan acquired through the treaty exchanging Sakhalin for the Kurile Islands. Even if this interpretation can be assumed to be correct, the fact remains that at this point in time the Soviet government had not yet taken measures to nationalize Etorofu Island, the Habomai Islands, Kunashiri Island, or Shikotan Island. This provides further evidence that Stalin regularly relied on the older Russian boundary in defining the Kurile Islands, that is to say the 18 islands north of Uruppu Island.

B. The San Francisco Peace Treaty

The San Francisco Peace Treaty was signed on September 8, 1951, officially ending World War II six years after fighting had ceased. While most of the Allied nations that had faced Japan in the war ratified the treaty, a handful, including the Soviet Union, did not. For signatory states, however, the SFPT came into force on April 28, 1952. With regard to Japanese territory, the Allied Powers in Chapter 2, Article 2 (c) of the treaty specified that Japan renounce "all right, title and claim to the Kurile Islands, and to that portion of Sakhalin and the islands adjacent to it over which Japan acquired sovereignty as a consequence of the Treaty of Portsmouth of September 5, 1905."

Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru at the San Francisco Peace Conference stated during deliberations over the final draft of the treaty that "with respect to the Kuriles and South Sakhalin, I cannot yield to the claim of the Soviet Delegate that Japan had grabbed them by aggression. At the time of the opening of Japan, her ownership of two islands of Etorofu and Kunashiri of the South Kuriles was not questioned at all by the Czarist government."[37] While Yoshida's argument aroused the interest of other delegates, it only became part of the official record and had no influence whatsoever in defining the boundary or in providing reservations as to the extent of the Kurile Islands Japan was to relinquish.

Soviet delegation Andrei Gromyko had two days prior to Yoshida's statement criticized the stance of Britain and the United States at the conference, saying it violated[38] the pledge under the Yalta Agreement that Japan would return Karafuto and hand over the Kurile Islands to the Soviet Union. In his address he requested that Article 2 (c) of the draft treaty be revised to say that Japan recognize the rights of the Soviet Union to the southern part of the Sakhalin Island and all the islands adjacent to it, as well as to the Kurile Islands, and renounce all right, title, and claim to these territories.[39] Delegations were unable to reach consensus over this and other proposed revisions and additions to the draft treaty, however, and the Soviet Union ultimately abstained from signing the SFPT on the grounds that it did not ensure peace.

US delegate member John Dulles addressing the conference expressed America's stance on the issue of Japanese sovereignty, saying: "Some question has been raised as to whether the geographical name 'Kurile Islands' mentioned in article 2 (c) includes the Habomai Islands. It is the view of the United States that it does not."[40]

As the above incidents illustrate, the SFPT failed in defining the boundary of the Kurile Islands or including reservations, and by not specifying the area Japan was to relinquish left the status of the island chain up in the air. If the language of the treaty is to be taken to have more than a general meaning, then to avoid misinterpretation it needs to provide a specific definition or include reservations. However, even though the SFPT does not refer to a specific area of the Kurile Islands, this does not necessarily mean the treaty uses the standard geographic definition of the chain. In fact, it would be more natural to assume that in reference to the Kurile Islands, treaty drafters were using the definition as it was understood in other international documents.

The Allied nations and Japan as signatories of the SFPT are bound by the treaty, whereas Russia is not. However, since Japan relinquished its claim to southern Karafuto and the Kurile Islands under the SFPT, it does not have the right in its relation with Russia to maintain a claim of sovereign over the territories.[41] In fact it does not even have the authority to argue over the territory it returned. Obviously, though, this condition does not apply to Japan's sovereign territory of Etorofu Island and Kunashiri Island in the Kurile Islands and the Habomai Islands and Shikotan Island in Hokkaido.

C. Soviet International Law Textbooks

In addressing the issue of redrawing national boundaries Soviet-era textbooks stipulate that for border changes to be recognized they need to be (1) decided by a referendum and (2) that the transfer of territory must be carried out willingly to ensure continued peaceful relations between neighboring states. In addition, these tomes state that internationally recognized treaties are an appropriate means for resolving territorial disputes in that the claims of countries that have lost territory are based on historical factors. The 1945 Yalta Agreement is an excellent example of this form of territory transfer in that it provides for southern Karafuto, which Japan took control of following the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War, and that portion of the Kurile Islands the Russian Empire had discovered and held up to 1875 to be returned to the Soviet Union.[42]

Seen in this light, World War II may have resulted in Japan returning southern Karafuto and the Kurile Islands to the Soviet Union, but only the area of the Kurile chain that was part of Russia's territorial claim up to 1875. In this sense, the descriptions within Soviet legal texts are in alignment with the arguments and conclusions I draw above in showing that Stalin and Bahmurov respectively used "all the Kuriles" and "all the Kurile Islands," names with differing meanings, to discuss Russia's claim to the "Kurile Islands" that excluded Etorofu and Kunashiri Islands.

Stalin's understanding of the geographic division of the Kurile chain is an exact match of the Japanese government's. This is certainly because Stalin knew the long, rich history of Russo-Japanese relations better than the other leaders of the Allied nations. In fact, it was not until September 7, 1956, that the US government officially recognized that Etorofu and Kunashiri Islands were sovereign territory of Japan and not part of the Kurile Islands controlled by Russia.[43]

As I pointed out above, the Yalta Agreement called for the Kurile Islands to be "handed over" and not "returned" since Japan had not taken the territory through violence and greed. This is why G. I. Tunkin, a Soviet scholar of international law, put forward a theory based on the sanctions related to international responsibility of a state[44] supporting Etorofu and Kunashiri's inclusion in the Soviet Union nationalizing the Kurile Islands based on Russian territorial claim of 1875. In his book Theory of International Law Tunkin says:

The taking of certain territories from Germany and Japan in consequence of the Second World War differs fundamentally from the previous seizures of territory which took place on the basis of the "right of the victor." The actions of the allies with regard to Germany and Japan were based above all on the principle of international legal state responsibility for the aggression which it committed. The juridical classification of the taking of certain territories from Germany and Japan which was done in connection with the Second World War, in those instances when this taking went beyond the limits of compensating the respective states for territories previously seized from them by Germany and Japan, is completely different from the seizure of territory on the basis of the "right of the victor."[45] (Italics are mine.)

In a separate issue from the "return" of southern Karafuto to the Soviet Union, Tunkin justifies Russian seizure of part of the Kurile Islands "beyond the limits of compensating the respective states for territories" to be "handed over" as part of international treaties not as the "right of the victor," but as reprisal for Japan initiating an illegal war of aggression. However, this argument that Japan's entrance into World War II was illegal under international law needs to be considered more closely if it is to be used to justify and authorize the Soviet Union capturing Japanese sovereign land by force.

6. Conclusion

In this paper I outlined the theory that Stalin excluded Etorofu and Kunashiri Islands from the Kurile Islands and that Soviet measures to incorporate territory in East Asia did not include either of these two islands in the Kurile chain, let alone the Habomai Islands and Shikotan Island. I also established that international law provides scant support for the Soviet Union's argument that the territorial dispute between Japan and Russia is resolved. In fact, I would argue that as the self-proclaimed leader of the proletariat, the Soviet Union in its so-called settling of the territorial issue with Japan would have disappointed the very masses it claimed to represent.

Under General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev's policy of perestroika and in the wake of the 1986 Reykjavik Summit with US President Ronald Reagan, the USSR on December 8, 1991 voted to create a Commonwealth of Independent States. Then on December 25, the Soviet Union came to an end, nearly 70 years after its founding in 1922. While these events were transpiring, Boris Yeltsin in an address at the Asian Affairs Research Council on January 16, 1990, announced a "five-stage proposal for the solution to the Northern Territories issue,"[46] in which he said that the Soviet Union was prepared to publicly acknowledge the territorial issue and draw Japan closer so as to conclude a peace treaty between both nations. This was a significant moment as it represented the USSR's long-awaited recognition of the Northern Territories issue. The Russian Federation inherited the dispute of the four northern islands following the fall of the Soviet Union.

Three years later, Yeltsin as president of Russia affirmed Moscow's commitment to conclude a peace treaty by signing the Tokyo Declaration on Japan-Russian Relations[47] on October 13, 1993. Paragraph 2 of the declaration states that the Prime Minister of Japan and the President of the Russian Federation

agree that negotiations towards an early conclusion of a peace treaty through the solution of this issue on the basis of historical and legal facts and based on the documents produced with the two countries' agreement as well as on the principles of law and justice should continue, and that the relations between the two countries should thus be fully normalized.

In addition, Yeltsin and Japanese then Prime Minister Hashimoto Ryutaro concluded the Kawana Agreement on April 19, 1998, specifying both leaders agreed that "the peace treaty should contain a solution to the issue of the attribution of the Four Islands on the basis of paragraph 2 of the Tokyo Declaration, and also incorporate the principles governing Japan-Russia friendship and cooperation as we move into the Twenty-first century."[48]

Yeltsin's successor President Vladimir Putin has on multiple occasions expressed a similar commitment to conclude a peace treaty to resolve the issue over the four northern islands and normalize Japan-Russian relations, including the Irkutsk Statement on March 25, 2001,[49] the joint statement with then Prime Minister of Japan Junichiro Koizumi on January 10, 2003,[50] and the Joint Declaration on Developing Bilateral Partnership on April 29, 2013.[51] However, while Yeltsin and Putin pledged to resolve the territorial dispute and both Japanese and Russian governments are moving in the direction of negotiating a peace treaty, there has been no mention of how the issue of the four islands is to be resolved.

When the two sides finally get around to deciding the issue, I hope that Russia will not disregard Stalin's historic boundary of the Kurile Islands and Lenin's principles of not seeking indemnities or the seizure of foreign lands as relics of its communist past. Japan, on the other hand, must not allow the emotionally charged nature of the issue get in the way, as it often has, and keep up its tireless efforts to ensure the return of the four northern islands.

- The use of Russia or the Soviet Union in the text and cited materials corresponds to the official name used in Japan at that time.

- Pages 2-3 of the October 1978 issue of Warerano hoppo ryodo (

- "Ikeda sori ate Furushichofu shusho no shokan (December 8, 1961)" (A Letter to Prime Minister Ikeda from Premier Khrushchev on December 8, 1961), in Northern Territories Issue Association, Hoppo ryodo mondai shiryoshu (Collection of Documents on the Northern Territories Issue), (Tokyo: Northern Territories Issue Association, 1972), pp. 235-236.

- Ryodo mondai ni kansuru sorenpo gaimusho koto seimei ni taisuru nihonkoku seifu no hanron (March 20, 1978)," (Japan's Response to the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs Spoken Statement on the Northern Territories [March 20, 1978]), in Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Northern Territories, pp. 55-56.

- It is important to note that the name can also serve as a general geographic term.

- Officially the Treaty of Commerce, Navigation, and Delimitation between Japan and Russia was signed in Shimoda on February 7, 1855, and the instruments of ratification lodged on December 7, 1856.

- The Treaty for the Exchange of Sakhalin for the Kurile Islands was signed in St. Petersburg on May 7, 1875 and the instrument of ratification lodged in Tokyo on August 22.

- The treaty, which ended the 1941-1945 war with Japan, was signed on September 8, 1951, and went into force on April 28, 1952.

- The treaty, which ended the 1941-1945 war with Japan, was signed on September 8, 1951, and went into force on April 28, 1952.

- It is important to note that the Habomai Islands and Shikotan Island are part of Hokkaido, not the Kurile Islands.

- The Joint Declaration by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and Japan was signed in Moscow on October 19, 1956.

- Key Axis Power nations included Bulgaria, Finland, Germany, Italy, Japan, Hungary, Romania, and Thailand.

- Key Allied Power nations included Australia, Britain, Canada, China, France, New Zealand, and the United States.

- Japan and the USSR signed the Japanese-Soviet Non-aggression Pact on April 13, 1941. The treaty, also known as the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact, ensured a five-year period of neutrality between the two nations. Article 3 stipulated the agreement would be automatically extended for another five years unless either side renounced the pact one year prior to the end of its term. The USSR renounced the neutrality agreement on April 5, 1945, following secretly deciding at the Yalta Conference to enter the war against Japan. Even though the terms of the pact were still in force, Soviet forces crossed into Japanese-held Manchuria and northeast China in the early hours of August 9, 1945.

- Here I am referring to the Republic of China. The People's Republic of China had not yet been formed.

- See "Yaruta Kyotei no hoteki kento" (Legal Considerations of the Yalta Agreement: Record of Discussion in the US Congress on March 18, 1952) in Hoppo ryodo mondai shiryoshu, pp. 133-148.

- "Nis-So kosho ni taisuru beikoku oboegaki (September 7, 1956)" (US Notes on Russo-Japanese Negotiations [September 7, 1956]), Northern Territories, p.35.

- John J. Stephan, The Kuril Islands: Russo-Japanese Frontier in the Pacific (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974), p. 153.

- In the decree, which passed the Second All-Russia Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies on November 8, 1917, Lenin calls for negotiations to bring an end to World War I through peace "without indemnities" and "without the seizure of foreign lands, without the forcible incorporation of foreign nations."

- J. Stephan, The Kuril Islands, p. 155.

- J. Stephan, The Kuril Islands, pp. 154-155.

- Officially called the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender.

- A total of 26 Allied countries signed the Declaration by the United Nations on January 1, 1942, pledging to not make a separate armistice or peace with Germany, Italy, and Japan.

- "Morotofu yori Sato taishi ni shukoshita sensentsukokubun" (Notice of the Declaration of War Handed to Ambassador Sato by Molotov) in Hopporyodo mondai shiryoshu, p. 38.

- "Mariku taishi yori Togo gaimu daijin ni shukoshita sensentsukokubun oyobi kaigiroku" (Meeting Notes and Notice of the Declaration of War Handed to Foreign Minister Togo by Ambassador Marik), Hoppo ryodo mondai shiryoshu, pp. 38-41.

- Harry. S. Truman, Memoirs, vol. 1, Year of Decisions (NY: Doubleday, 1955), p. 440.

- Ibid.

- Truman, Memoirs, vol. 1, p. 441.

- Suizu Mitsuru, Hoppo ryodo dakkan e no michi (Reclaiming the Northern Territories) (Tokyo: Nihon Kogyo Shimbunsha, 1979), p. 83.

- Truman, Memoirs, vol. 1, pp. 442-443.

- Sbornik zakonov SSSR; ukazov Prezidiuma Verkhovnogo Sovieta SSSR 1938-1975 (Collection of Laws of the USSR and Decrees of the Supreme Soviet Presidium of the USSR, 1938-1975) vol. 1, (Moscow, 1975), pp. 50-51.

- Collection of Laws of the USSR, p. 94.

- Irie Keishiro, "Senryo kanrika no hoppo ryodo" (The Northern Territories Under Occupation), Kokusaiho gaiko zasshi vol. 60, no. 4, 5, 6 of six volume compendium, (1962), p. 144.

- Collection of Laws of the USSR, p. 95.

- Izvestia, March 17, 1948.

- Izvestia, March 14, 1948.

- Sanfuransisko kaigi gijiroku (Minutes of the San Francisco Peace Conference), (Tokyo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, September 1951), p. 302.

- Minutes of the San Francisco Peace Conference, p. 108.

- Minutes of the San Francisco Peace Conference, p. 112.

- Minutes of the San Francisco Peace Conference, p. 33.

- Takano Yuichi, "Hoppo ryodo no hori" (Legal Doctrine of the Northern Territories), Kokusaiho gaiko zasshi, p. 232.

- Institute of Law of the Academy of Sciences, International Law (Moscow 1959); Sobieto kokusaiho (Soviet International Law). Japanese translation of Russian edition by Nikkan Rodo Tsushinsha (1962), pp. 254-258; Kokusaiho (International Law) vol. 1, Iwabuchi Setsuo, Nagao Kenzo, trans., Institute of Law of the Academy of Sciences, ed., (Tokyo: Nihon Hyoronsha, 1962), pp. 206-210.

- "Nis-So kosho ni taisuru beikoku oboegaki" (US Notes on Russo-Japanese Negotiations [September 7, 1956]), Northern Territories, p.36.

- For the legal nature of state responsibility see my work "Kokka no kokusai sekinin ni kansuru ichikōsatsu" (A Study of International Responsibility of States), in Shin boei ronshu vol. 7 no. 4 (March 1980).

- G.I. Tunkin, Theory of International Law, translated by William E. Butler (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974), pp. 414-415.

- "Hoppo ryodo 5dankai kaiketsuron" (The Five-Stage Solution to the Northern Territories Issue), Northern Territories (March 2014, appendix), p. 35.

- "Tokyo Declaration on Japan-Russia Relations," October 13, 1993. English translation published on the Foreign Ministry's website at http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/n-america/us/q&a/declaration.html.

- Excerpt from The Kawana Agreement. English translation published on the Foreign Ministry's website at

- "Irkutsk Statement by the Prime Minister of Japan and the President of the Russian Federation on the Continuation of Future Negotiations on the Issue of a Peace Treaty," March 25, 2001. English translation published on the Foreign Ministry's website at http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/europe/russia/pmv0103/state.html.

- "Joint Statement by Prime Minister of Japan Junichiro Koizumi and President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin Concerning the Adoption of a Japan-Russia Action Plan," January 10, 2003. English translation published on the Foreign Ministry's website at http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/europe/russia/pmv0301/joint.html.

- "Nichi-Ro patonashippu no hatten ni kansuru Nihonkoku sori daijin oyobi Roshia renpo daitoryo no kyodo seimei" (Joint Statement by the Prime Minister of Japan President of the Russian Federation Concerning Developing Japan-Russia Partnership [April 29, 2013]), Northern Territories (March, 2014), p. 51.

Northern Territories) published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan Public Information and Cultural Affairs Bureau refers to the four northern islands of "Etorofu Island, the Habomai Islands, Kunashiri Island, and Shikotan Island, which the Japanese government has in the nearly 30 years since they were occupied at the end of World War II called on the Soviet Union to return" as hoppo ryodo, or Northern Territories.

http://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/other/bluebook/1999/I-c.html#2

RSS

RSS