The Positions of the United States and the United Kingdom regarding the Senkaku Islands at the time of the Okinawa Reversion

Sep 15, 2022 PDF Download

Introduction

Japan, after its defeat in World war II in August 1945, signed the Peace Treaty with the allied nations in 1952, and international law relations between these contracting partis changed from wartime to peacetime in international relations.[1] Article 3 of the treaty stipulated that the Nansei Islands[2] south of 29° north latitude, the Nanpo Islands[3] south of theSofu Gan Island and Parece Vela (the Ogasawara Islands) and Marcus Island (Minamitorishima Island) would be placed under the trusteeship of the United States as sole administering authority.

After these regions were placed under the administration of the United States, the U.S. enacted several decrees, such as The Law Concerning the Organization of the Gunto Governments, Provisions of the Government of the Ryukyu Islands, and Civil Administration Proclamations. the geographical boundaries of the Ryukyu Islands were delineated by latitude by the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands (USCAR), which included the Senkaku Islands within USCAR’s administrational jurisdictions.[4] Japan maintained territorial sovereignty, including the right of disposition (i.e. jus disponendi), and residual sovereignty over these islands, despite the U.S administering authority.

On August 15, 1945, Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration. The Japanese constitution, which is based on the principles outlined in the declaration, was promulgated on November 3, 1946. Article 9 of the Constitution stipulates that Japan would renounce its right to war, its right to maintain a military force, and its right to belligerency.[5] In other words, Japan was rendered defenseless to foreign invaders as it no longer possessed the ability to muster an organized counteroffensive. Article 5 of the Peace Treaty with Japan stipulates that Japan would rely on the collective defense of the United Nations for its own self-defense. Article 6(a) of the treaty mandated that the Allies end their occupation of Japan and withdraw their forces within 90 days after signing the treaty. Simultaneously, this article enabled the U.S. to station their forces within Japan, and the U.S. needs to sign status of force agreement (SOFA) with Japan for more stationing.

The U.S., to ensure Japan’s security, signed the Security Treaty Between the United States of America and Japan on the same day that the Peace Treaty with Japan was signed.[6] As such the U.S. secured the right for its forces to be stationed within Japan. Additionally, the two countries signed an agreement regarding the status of the U.S. forces stationed in Japan based on Article 6 of the treaty, in exchange for Japan providing base facilities to the U.S.[7] In 1960 the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty and the SOFA were revised, and United States forces have been stationed in Japan under the new SOFA to this day.

Later, territories which had been placed under the administration of the U.S. were gradually returned to Japan. The last of these were the Nansei Islands. After many developments, the U.S. agreed to return these islands to Japanese control during the 1969 Japan-U.S. Summit Talk.[8] The two countries signed the 1971 Okinawa Reversion Agreement and Okinawa was reverted to Japanese control on May 15, 1972.[9]

The U.S. and the United Kingdom had to clarify their positions on the Senkaku Islands as they would be returned to Japan with the conclusion of the Okinawa Reversion Agreement. This was done considering the tense security environment in East Asia generated by both People’s Republic of China (hereinafter China) and Republic of China (hereinafter Taiwan) also laying claim to the islands, thus creating the potential for armed conflict. This short work endeavors to introduce how the United States and the United Kingdom viewed the Senkaku Islands at the time of the Okinawa Reversion, based upon papers written at the time.

Uotsuri Island of the Senkaku Islands

(source: https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/ryodo/senkaku/gallery/index.html#&gid=1&pid=1)

1 China’s sovereignty claim over the Senkaku Islands and the Okinawa Reversion

Taiwan grew interested in the territorial status of Okinawa during the 1950s. Once the return of Okinawa became a topic of consideration, Taiwan unofficially courted the U.S. Department of State to jockey for Okinawa to be handed over to Taiwan rather than to be returned to Japan.[10] The Committee for the Coordination of Joint Prospecting for Mineral Resources in Asian Offshore Areas (CCOP) at the United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East (ECAFE) conducted a mineral survey from October 12, 1968 to November 29 of that year. The survey, which concerned the East China and Yellow Seas, indicated the potential of oil reserves in these waters.[11] These results gave rise to deferent of opinion of sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea.

On July 17, 1970, the Taiwanese Government approved a concession (i.e. a petroleum exploration contract) between China(Taiwan) Petroleum Corporation (CPC) and Pacific & Gulf Oil Company. This contract granted the latter prospecting rights to an area of the continental shelf in the East China Sea delineated to fall within 25° to 27° north latitude, and 121° to 125° east longitude.[12] However, Japan filed a protest with Taiwan given that this area overlapped with the area that the Japanese Government reserved for a Japanese oil developer. Later, Pacific & Gulf Oil as well as Conoco Inc. pulled out of the production framework after the U.S. government indicated in the mid-1970s that it would not ensure the protection of their interests.[13] Consequently the dispute between Japan and Taiwan subsided.

It is a well-known fact that China abruptly began its own sovereignty claims over the Senkaku Islands immediately after the CCOP report. China on December 30, 1971, objected to Uotsuri Island and other islands being incorporated within the scope of the territory of Japan to be returned within the Okinawa Reversion Agreement. China issued a statement in protest, claiming “This is a gross encroachment upon China’s territorial integrity and sovereignty.”[14] China also claimed the following three points. (1) The islands were already included within China’s defensive zone as early as the Ming Dynasty, as the islands appertain to Taiwan rather than Ryukyu or present-day Okinawa. (2) The boundary between China and Ryukyu in the region is delineated between Chiwei (Taisho) Island and Kume Island. (3) Japan stole these islands during the Sino-Japanese War by pressuring the Qing Dynasty Government to sign the Treaty of Shimonoseki and cede the Island of Formosa (i.e. Taiwan) together with all Islands appertaining or belonging to the said Island of Formosa along with the Pescadores Islands. Furthermore, Japan as the aggressor plundered these territories from China, and thus its claims of sovereignty are based on blatant logic akin to a thief pilfering goods.

The weakest point in Chinese territorial claims over the Senkaku Islands is that it neglected to make its case for sovereignty, not even once, during the 75-year period between Japan originally incorporating the Senkaku Islands and the announcement of the CCOP report. This is indicative of the fact that the basis for Chinese territorial claim is to seek the waters around the islands as well as gaining exclusive control of the natural resources that the Senkaku Islands offer, such as the marine petroleum endowments and sea-floor hydrothermal deposits found in their surrounding waters. Simultaneously, another major goal is Chinese ambitious for the national security benefit of securing a route to the Pacific Ocean for the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). It has even been reported that China announced in 2013 that the Senkaku Islands were critical national interests and that it would secure the islands even if it required the use of military force.

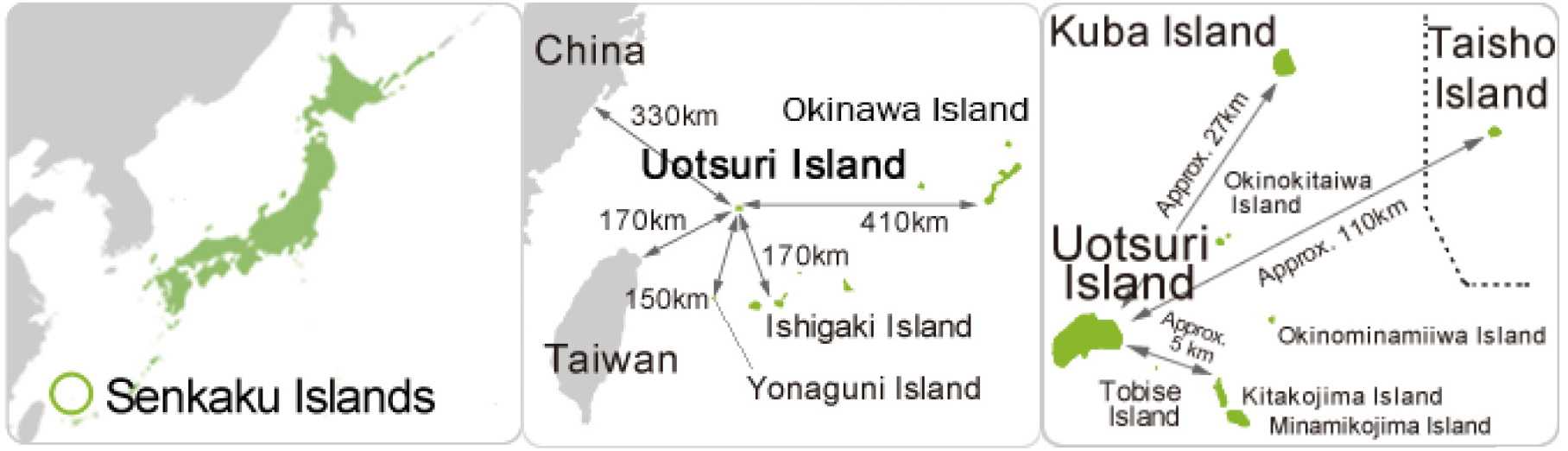

(source: https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/senkaku/index.html)

2 The Senkaku Islands problem and the position of the United States of America

During trusteeship of Okinawa, the U.S. exercised its administrative rights over the Senkaku Islands. When the U.S. made the decision to return Okinawa, which includes the Senkaku Islands, to Japan it needed to determine its position on the islands and thus confront the territorial claims of Taiwan and China.[15] This is as a consequence of Article 5 of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the U.S. and Japan (the revised version of it was effectuated in 1960) which states that in the case of an armed attack occurred in territories under Japanese administration, both parties would cooperate to address the threat. In other words, if China were to carry out a military assault on the Senkaku Islands, the U.S., in accordance with its own constitutional proceedings, would respond to the attack along with Japan.

The U.S. drafted secret documents summarizing five points which defined its stance on the Senkaku Islands, noting that other parties such as China and Taiwan had also requested that the Ryukyu Islands should not be returned to Japan.[16]

Firstly, these papers clarified the U.S. position towards the Okinawa reversion.[17] Maps of the U.S. and Japan at the time of World War II indicate the Senkaku Islands as appertaining to Okinawa prefecture and being governed by Japan. These maps prove that the Senkaku Islands were included in the territories that were taken over by the U.S. in accordance with Article 3 of the Peace Treaty with Japan. Therefore, returning these territories would not infringe upon the U.S. basic stance of not getting bogged down in sovereignty disputes. The document also mentions Chinese mistrust of the U.S. position on the Senkaku Islands.[18] They note that the Okinawa Reversion Agreement maintained Kuba Island and Taisho Island of the Senkaku Islands for firing ranges for U.S. Navy, and China criticizes the U.S. position as pro-Japan. Moreover, these documents indicate that China cites the agreement as proof of its assertion that the U.S position lacks neutrality.

The third point of the document touches upon the U.S. neutrality in relation to Article 5 of the new U.S.-Japan Security Treaty.[19] Article 5 states, "Each Party recognizes that an armed attack against either Party in the territories under the administration of Japan would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common danger…” The papers mention that some Japanese argue that applying Article 5 to defend the Senkaku Islands from Chinese incursion would not fall in line with the U.S official position of neutrality given that it has officially acknowledged that it would return the sovereignty of Okinawa including the Senkaku Islands to Japan. It was also mentioned that the Japanese Government, as well as media outlets, had for some time intentionally avoided broaching the topic of the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the Senkaku Islands issue, despite being fully aware that the scenario posed a glaring inconsistency with the U.S. fundamental position. Therefore, it is conceivable that the U.S. fully aware of this predicament, must have anticipated that Article 5 would become the focus of attention if the Senkaku issue worsened between Japan and China – especially if oil reserves were to be found.

The papers noted American oil companies operating in Japanese waters as a concern.[20] Several of the drill sites in which American oil companies were licensed to operate by both the South Korean and Taiwanese governments overlapped with areas over which Japan claimed sovereignty. The waters surrounding the Senkaku islands, which were licensed to Pacific & Gulf Oil Company, were particularly concerning as they could cause friction with the Chinese Nationalist Party or the mainland Chinese Communist Party. The U.S. Government raised a warning to all American oil companies and spoke with each interested government, explaining that the U.S. has no interest in becoming a party to the territorial disputes surrounding the North Asian continental shelf. In this manner, the U.S. concluded that it would be able to avoid direct involvement in the matter for the time being.

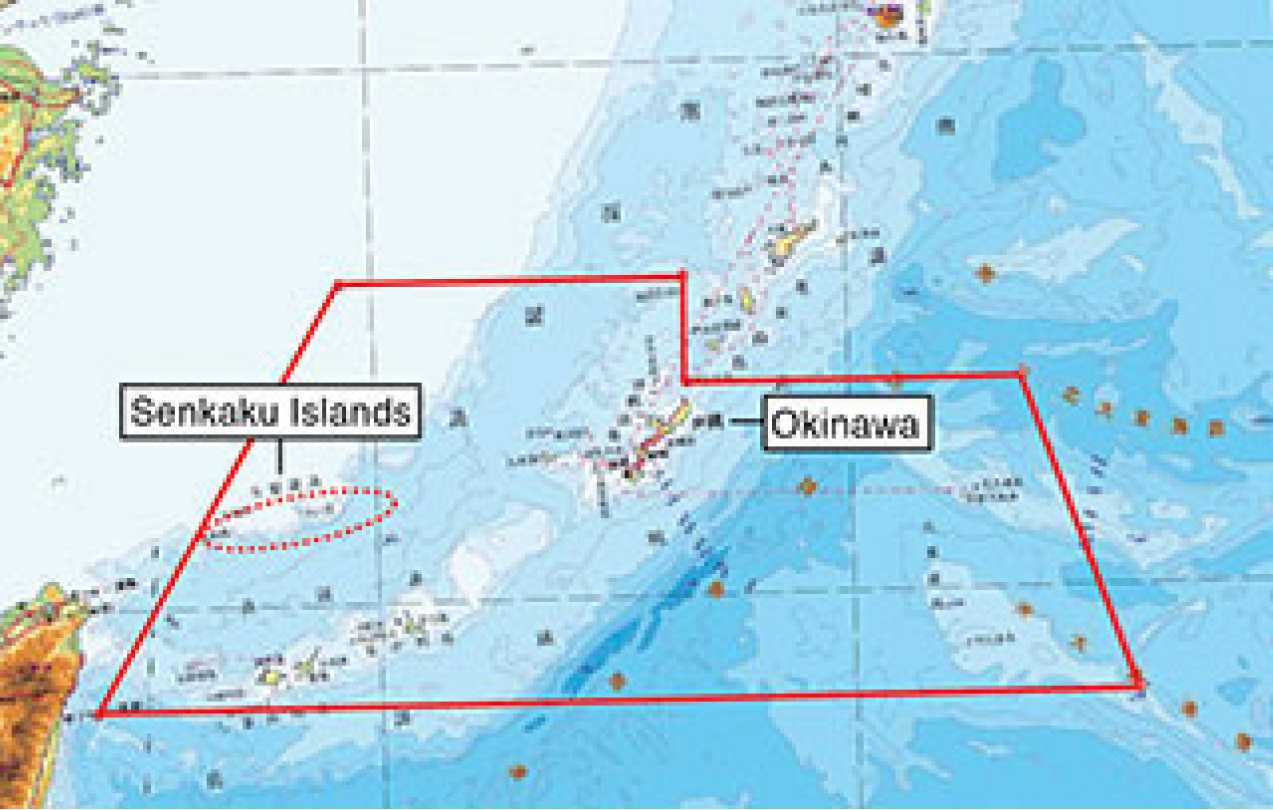

(https://www.mofa.go.jp/a_o/c_m1/senkaku/page1we_000010.html, The administrative rights of all of the islands within the area inside the straight lines on the map were returned to Japan in 1972 in accordance with the Okinawa Reversion Agreement. The Senkaku Islands are included in this area.)

3 British stance on the Senkaku Islands

China proclaimed its independence on October 1 of 1949. The Soviet Union promptly recognized China the following day, followed by Bulgaria on October 3, Burma on December 6, and India on December 30, 1949. The United Kingdom, which had recognized Taiwan, was the first Western country to recognize Chinese communist government on January 6, 1950. The U.K., despite recognizing the Chinese government, became the first country to continue its working relationship with Taiwan, establishing a de facto diplomatic relation through which it maintained its trade and consular ties.[21]

The U.K. was not adamantly involved in Asian post-war policies, focusing rather on European affairs. Nevertheless, the British Government drafted a secret memorandum reassessing the circumstances of the Senkaku Islands, as the Islands could become the center of a dispute between Japan, Taiwan, and China, if the United States were to return its administrational rights to Japan under Article 3 of the Peace Treaty with Japan.[22]

The memorandum offers a comprehensive summary of the history and legal status of the islands. Moreover it acknowledges the fact that China began disputing Japan’s title to the Senkaku Islands on December 29, 1970 after the possibility that the nearby continental shelf may be home to oil reserves had arisen.[23] The document elucidated the British stance on the Senkaku Islands, raising the following seven points: (1) the geographical circumstances of the islets, (2) the U.K.’s initial understanding of the Senkaku Islands, (3) legal status of the Ryukyu Islands, (4) the relationship between the Ryukyu and Senkaku islands, (5) the history of the Senkaku Islands from 1896 to 1945, (6) the history of the islands from 1945, and (7) sovereignty claims over the Senkaku Islands as well as counterarguments.[24]

The memorandum opens by noting the geographical aspects of the Senkaku Islands with maps.[25] It acknowledges that the Senkaku Islands are a group of uninhabited islands sporadically located in the East China Sea at 124° east longitude and 25°55 ’north latitude.[26] The islands are located 150 nautical miles from Ishigaki Island and 100nm from Taiwain’s Keelung City. They are separated from the Ryukyu Islands by the Okinawa Trough, a maritime trench that is 500nm wide and 2000m deep. A portion of the Senkaku Islands are clearly indicated on maps published in London between 1794 and 1832. British Royal Navy sea-charts from 1876 (later amended in 1881) of the East China Sea (Map No. 1262) also indicate the Islands. The maps do not cite the ownership of the islands, but at the very least suggest the Chinese knew of the islands at the end of the 18th century.[27]

The memorandum discusses the status of the Ryukyu Islands,[28] citing official documents from the British Government, as well as the relationship between the Ryukyu and Senkaku islands.[29] The history of the Ryukyu Islands was also covered; the islands were recognized from the beginning of the 17th century as a quasi-independent state that paid tribute to both the Chinese Emperor and the rulers of the Satsuma Domain in Japan. The denizens of the Ryukyu Islands were recognized as members of the Japanese race who spoke a dialect of Japanese. However, these denizens also adopted rituals, practices, and an ephemeris from China. China opposed Japan’s annexation of the Ryuku Islands in 1879, bringing conflict to the forefront. Former U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant, who was touring the Far East at the time, urged Japan and Qing dynasty to discuss a proposal for the partition of the Sakishima Islands through an arbitration committee. The two sides discussed the proposition in the summer of 1880, but to no avail. British documents noted that peace talks after the First Sino-Japanese War as well as the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki, which ceded control of Taiwan to Japan, made no mention of the Senkaku Islands.

As for the relationship between the Ryukyu and Senkaku islands, it is unclear as to whether the latter were mentioned during the negotiations over the former which ensued between 1879 and 1880. Thus, Japan had not asserted that the Senkaku Islands were included within the Ryukyu Islands as of 1894 at the latest. The Japanese Government first expressed interest in the Senkaku Islands after a merchant named Koga Tatsushiro discovered them in 1884. The islands were incorporated into Okinawa Prefecture in 1895 and placed under the administrative jurisdiction of Ishigaki – a town located in the Yaeyama District of the prefecture. There are no documents held by the British Government indicating that the Senkaku Islands were discussed during these negotiations. Furthermore, the Treaty of Shimonoseki does not list Taiwan’s appertaining islands. It is probable that Japan became interested in the Senkaku Islands after acquiring Taiwan.

The memorandum next discusses the history of the Senkaku Islands harking back to Japan’s occupation of the islands in 1896 to Japan’s defeat in 1945,[30] as well as the post-war period from 1945.[31] The document cites articles published by the Japanese press which indicate that a group of Japanese settlers made landfall on the islands sometime during 1897 or 1898. A Japanese survey mission named the Islands as the Senkaku Islands in 1900. The documents also indicate that a member of the island chain was given to a Japanese citizen residing in Okinawa during the 1920s. However, this island has hitherto remained uninhabited. Maps of Japan drafted by the British War Office in 1923 explicitly label the territory as the Senkaku Islands. After 1945 the Senkaku Islands were governed by USCAR as part of the Ryukyu Islands. The memorandum determines that there is no evidence of China protesting American governance of the Senkaku Islands.

Lastly, the memorandum mentions articles published around 1971 in Chinese newspapers and magazines, summarizing the various sovereignty claims as well as counterarguments repeatedly made between Japan, China, and Taiwan.[32] The dispute between Japan and Taiwan stems from the latter granting development rights to the Pacific & Gulf Oil Company for a maritime mining site. Japan argued that Taiwan had no legal basis for granting these rights. Taiwan introduced a counterargument asserting that the waters in question are historically, geographically, and traditionally part of Taiwan’s continental shelf, given that Taiwan had ratified the Convention on the Continental Shelf in August of 1970. Meanwhile, China claimed the Senkaku Islands as Chinese territory on December 29 of 1970 in its People’s Daily, citing ‘ancient evidence ’without providing any evidence whatsoever. China claims that the islands appertain to its Taiwan Province.

The memorandum raises the fact that in April of 1971 the U.S. had not intervened in the dispute over the Senkaku Islands between Japan and China. It also notes that the islands, at the time, were governed by the U.S. as part of the Ryukyu Islands. Moreover, it notes that China claims all resources of the seabed, subsoil, and shallow water around the Senkaku Islands. The British document concludes that for the time being, China claims that continental shelves should be delineated through negotiation but would likely enter negotiations claiming that the Senkaku Islands were clearly Chinese territory.

Conclusion

This report documents how the U.S., a party to the Okinawa Reversion Agreement, has resolutely maintained its principal position in regard to the Senkaku Islands. Moreover, this position has been upheld even in the face of complications involving Article 5 of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. China, unlike at the time of the Okinawa reversion, is now big economic power which has dramatically strengthened its military capabilities and no longer obscures its ambitions of sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands. Some U.S. leaders have publicly announced that America would maintain its policy of non-interventionism by suggesting that the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty would not automatically be applied even if China were to stage a military attack on the Senkaku Islands.[33] These statements were made to improve relations with and to avoid confrontation with China. Afterwards, however, the U.S. declared that the Senkaku Islands are included within the territories under Japanese administration as stipulated within Article 5 of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, and that the U.S. as well as Japan would cooperate to address a military attack from China.

Meanwhile, the memorandum drafted by the United Kingdom upholds neutrality, the memorandum achieves this by carefully exploring the geographic and historic circumstances of the Senkaku Islands using documents procurable at the time of the Okinawa Reversion, while offering a juxtaposition of the respective sovereignty claims made by Japan, Taiwan, and China. It is intriguing that the memorandum takes note that China first claimed sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands shortly after the CCOP report which indicated the possibility of maritime oil resources. Furthermore, the memorandum points out that China has neglected to provide any documentation supporting its claims other than ancient texts.

- Even though the USSR was a member of the Allies, it refused to sign the Peace Treaty with Japan due to its dissatisfaction with Article 2(c) because the portion that stipulated that Japan would renounce all of its claims to the Kuril Island and Southern Sakhalin. Japan and the USSR signed the Soviet-Japanese Joint Declaration on Oct. 19, 1956, concluding both countries enjoy a provisional relationship under International peacetime law. However, the two sides must sign a peace treaty of the WW II.

- The scope encompassed the Ryukyu and Daito islands,

- TThe scope encompassed the Ogasawara Islands, Nishioshima Island and the Volcano (Iwo)Island.

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Bureau of Information and Culture, On the Senkaku Islands, 1972, p.7.

- Article 9 of the Japanese constitution stipulates: “(1) Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. (2) In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.”

- Article 1 of the Security Treaty Between the United States of America and Japan (signed on Sept. 8, 1951 and effectuated on Apr. 28, 1952).

- “Agreement under Article 6 of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between Japan and the United States of America, regarding Facilities and Areas and the Status of United States Armed Forces in Japan"

- After receiving the position paper of Japan, the U.S. Government drafted in May of 1969 the National Security Decision Memorandum 13 (NNDM13) ‘Policy Toward Japan.’ Details of the provisions requested by the U.S. Government to that of Japan regarding policy on post-reversion Okinawa during the negotiations thereof are outlined within Diplomatic negotiation on Okinawa reversion and Korea/Taiwan by S. Hatano, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Diplomatic Archives Gazette No.27 (Dec. 2013).

- Agreement between Japan and the United States of America Concerning the Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands (signed on Jun. 17, 1971, and effectuated on May 15, 1972).

- Op.cit. 9, p.28.

- Emery et al, Geological Structure and Some Water Characteristics of the East China Sea and Yellow Sea, in

Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East, Committee for Co-Ordination of Joint Prospecting for Mineral

Resources in Asian Offshore Areas (C.C.O.P) Technical Bulletin, vol. 2. 1969.

https://www.gsj.jp/publications/pub/ccop-bull/index.html, (as of Sept. 10, 2016) - Toshio Okuhara, The Senkaku Islands and Territorial claim issue④, Sanday Okinawa (Jul. 29, 1972).

- Fillmore C. F. Earney, Marine Mineral Resources (Routledge, reprinted 1990), p. 40.

https://www.google.co.jp/?gfe_rd=cr&ei=dM7gV7SOLeuQ8Qe0qr3YCA&gws_rd=ssl#q=Concession+between+Taiwa n+Government+and+Gulf+Firm (as of 19 September 2016) - ‘Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China Statement’ issued on Dec. 30, 1971, People’s China 2012 special edition, p.30.

- Okinawa, as stipulated by Article 3 of the Peace Treaty with Japan, could have been placed under the trusteeship of the United Nations if the U.S. had proposed to do so. However, the U.S. chose to return Okinawa to Japan.

- Department of State Briefing Paper Senkakus, (Secret, United States Department of State, August 1972) — ‘declassified’ (Authority NND977508) on Apr. 13, 1978.

- Ibid., para. 2.

- Ibid., para. 3.

- Ibid., para. 4.

- Ibid., para. 5.

- A. Takeshige, Business experience with countries of no diplomatic relations - An example of the United Kingdom

beginning in 1950,Report on Japan and Taiwan Relations, No. 9 (May 2007), p.15.

http://jats.gr.jp/journal/pdf/gakkaiho009_07.PDF (as of September 19, 2016) - Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Research Department Memorandum, The Senkaku Island, Department Series No 10. (File No. RR 2/10 Restricted), (12 August 1971), (Closed until 2002).

- Ibid., para. 1, p. 1.

- Ibid., p. 2.

- Ibid., para. 2, p. 3.

- Ibid., para. 3, p. 4.

- The Qianlong Emperor of the Qing Dynasty ruled continental China at the end of the 18th century. The People’s Republic of China did not exist at this time.

- Ibid., paras. 4-5, p. 5.

- Ibid., paras. 6-8, pp. 6-7.

- Ibid., para. 9, p. 7.

- Ibid., paras. 10-11, p. 7-8.

- Ibid., paras. 12-18, pp. 8-11.

- For instance, former United States Vice President Walter F. Mondale (Carter Administration, Jan. 1977 to Jan. 1981) while serving as the U.S. Ambassador to Japan (1993 to Dec. 1996) suggested in an interview that was quoted in the New York Times on October 20, 1996 that “the seizure of the [Senkaku] islands would not automatically set off the security treaty and force American military intervention." This comment was the cause of much uproar. Article details: Nicholas D. Kristof, Would You Fight for These Islands?, The New York Times, 20 October, 1996. http://www.nytimes.com/1996/10/20/weekinreview/would-you-fight-for-these-islands.html?_r=0 (as of October. 2, 2016)

RSS

RSS