1. Introduction

The issue of the Senkaku Islands (known in China and Taiwan as the Diaoyu and Diaoyutai) has been one of rising tension between Japan and China in recent years. Following repeated incursions into Japanese territory and territorial waters by Chinese people, both private and state actors, which have escalated over time, the Tokyo metropolitan governor Ishihara Shintaro announced a plan to purchase the islands from the Japanese landowner; this led to the national government's purchase of the islands in the autumn of 2012.

It is certainly important to clarify and analyze the particulars of this issue, which has taken on the tone of a territorial conflict fuelled by extreme Chinese nationalism, and to forecast likely future developments. Here, though, I would like to step back and offer some geopolitical considerations related to the Senkaku Islands from the perspectives of Japanese security and maritime interests.

2. Geographic Conditions

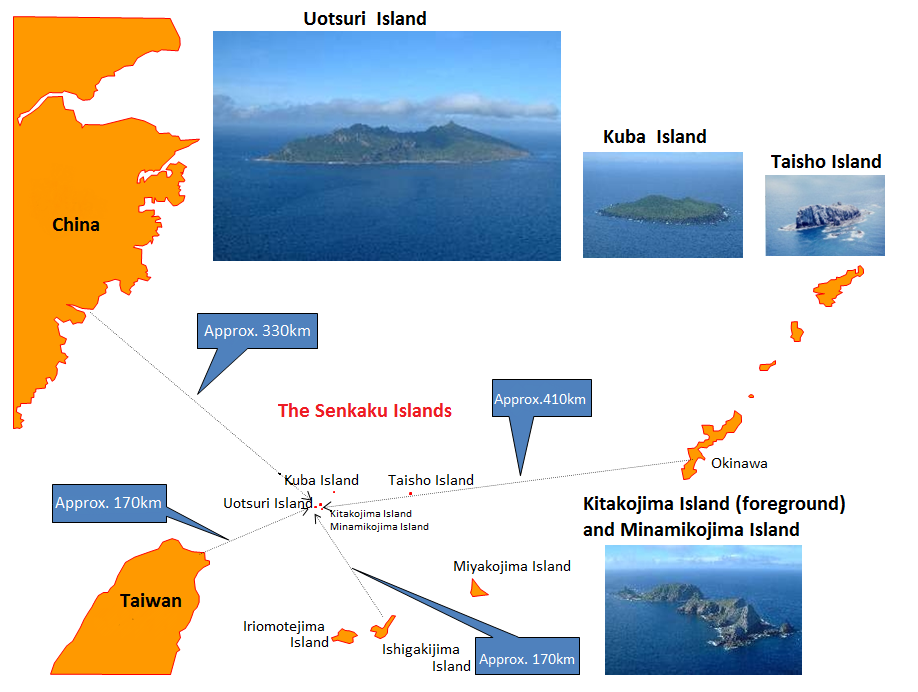

The Senkakus are located more or less at Japan's most southwesterly point. The exclusive economic zone associated with these islands abuts the EEZs of both China and Taiwan, as can be seen in Figure 1. While they do not function in the same way that Japan's island territories in the Pacific Ocean do, they nevertheless form a basis for a certain area of Japan's EEZ and continental shelf in the East China Sea.

Figure 1: Japan's territorial sea, contiguous zones, and EEZs

Note: Based on Japan Coast Guard materials.

Looking more precisely at the location of the Senkakus, we find them approximately 170 kilometers northwest from Ishigakijima Island, 170 kilometers northeast of the island of Taiwan, 330 kilometers southeast of continental China, and 410 kilometers west of the island of Okinawa. They are thus situated more or less in the center of the sea separating Japan, China, and Taiwan (see Figure 2). However, a look at a more detailed map shows that the islands are also just 140 kilometers from Pengjiayu, an island just north of Taiwan--a distance shorter than that to Japan's Ishigakijima Island.1 And in terms of geological formations, they are on the west side of the Okinawa Trough, which means they are placed on what China claims as a natural prolongation of the continental shelf extending from its shores.2

Figure 2: The position of the Senkaku Islands

Note: Based on Japan Coast Guard materials.

One thing to confirm here is the fact that none of this is related in any way to the conditions that define the territorial status of these islands. Takeshima, the Japanese territory now being illegally occupied by South Korea, is located closer to the Korean island of Ulleungdo than to Japan's Okinoshima Island. The Kinmen (Quemoy) and Matsu islands held by Taiwan are situated very close to the shore of continental China. Greece holds many islands found just off the coast of Turkey. For questions of territorial sovereignty, the process by which that territory has come into a state's possession is the key--be it by occupying terra nullius (land belonging to nobody), showing effective control over the territory, displaying the intention to possess the territory, or some other means recognized in international law--and the geographic status of that territory serves only to define its precise location.

In geopolitical terms, from the perspectives of maritime interests and security, the perceived value of island territories not held by the nearby state goes higher the closer they are to the mainland of that state. That nation will see its lack of control over this territory as a disadvantage; herein lie the seeds of conflict, whether or not there are actual reasons for it.

3. Legal Effects of Islands as Territory

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which went into effect in 1994, defines the area out to 12 nautical miles from the baseline of a coastal state's shore of as that state's territorial sea and the area out to 200 nautical miles from the baseline as its EEZ and its continental shelf (although the continental shelf can be extended out to 350 nautical miles from the baseline if certain conditions are met). In cases where two nations are less than 400 nautical miles from one another, their respective EEZs and continental shelves are to be delimited through bilateral discussions.

However the boundaries are determined, as Japanese territory, the Senkaku Islands give Japan a territorial sea, an EEZ, and a continental shelf with their shores as the baseline. The territorial sea out to 12 nautical miles from the islands, as well as the EEZ extending 200 nautical miles (or to points equidistant from them and other nations' shores), and the potentially extended continental shelf are all Japan's. This is not a statement of Japanese sovereignty over these waters, necessarily--a state merely has sovereign rights and management duties related to the natural resources found within an EEZ. While the scope of a state's continental shelf as defined in UNCLOS differs in some respects from that of an EEZ, in geopolitical terms it is treated in basically the same way. In this paper I will not offer separate explanations for areas classified as continental shelves and EEZs.

With the exception of the right of innocent passage granted to foreign ships passing through them by Article 17 of UNCLOS, territorial seas fundamentally have the same legal status as a state's land territory, and actions undertaken by foreign official or private entities within these seas are limited to those spelled out in relevant treaties.

With respect to EEZs, meanwhile, Article 56 of UNCLOS grants the coastal state the sovereign rights for exploring, exploiting, conserving, and managing the natural resources there, as well as jurisdiction for establishing artificial islands and other structures, undertaking marine scientific research, and preserving the marine environment. Here, though, as spelled out in Article 58, all other states enjoy the freedoms of navigation and overflight and of the laying of submarine cables and pipelines.

In the high seas located outside coastal states' EEZs, all nations enjoy the freedom of conventional usage of the seas, with the exception of some activities related to the deep ocean floor.

4. Maritime Interests and Security Matters

I will now move on to an outline of more specific issues related to Japan's maritime interests and security, keeping in mind the legal effects that the Senkaku Islands bring to bear as mentioned above. Indeed, geopolitical considerations in this context boil down to questions of a state's maritime interests and security.

For a coastal state, maritime interests first include things like fishery resources and the exploitation, management, and maintenance of oil, gas, and other natural resources. Other aspects of maritime interests include the coastal nation's maintenance of safe, reliable sea lanes to ensure the freedom of passage for all states, as well as its management and control of the seas to ensure the freedom of usage of those seas and its own security.

Fishery resources are treated as a biological resource in the same way as other natural resources. However, due to the large number of people involved in fishing, the importance of sustainability, the presence of migratory fishes that move across broad areas spanning EEZ boundaries, and other factors, there are numerous special treaties and agreements covering fishing and management of fishery resources. The involvement of various historical and other circumstances makes these a more complicated subject than other natural resources.

The development of oil, gas, and other nonbiological resources receive direct attention as maritime interests when states stake claims to EEZs and continental shelves or when they draw up boundaries to these areas. Coastal states hold sovereign rights over the natural resources in their EEZs, on the sea floors beneath these waters, and below those sea floors, making sovereignty over islands as a defining base point for broad EEZs a matter of national interest.

Rare earth elements and other nonferrous metals have attracted considerable attention as maritime natural resources, giving fresh importance to the resources lying within a state's EEZs. Also falling within the sovereign rights of coastal states are such oceanic energy resources as seawater, ocean currents, and wind.

Certain maritime activities are closely associated with these rights, including marine scientific research and preservation of the ocean environment, as well as construction and use of artificial islands, installations, and structures. These, too, fall under the jurisdiction of a coastal state. Scientific surveys can be carried out by nations other than the coastal state if the latter grants consent, but this consent is in principle always given. Surveys of natural resources, however, may not be undertaken by others without the coastal state's permission, as these resources fall under the sovereign rights of that state.

Trade lies at the core of a nation's economic activities, and the bulk of international trade takes place via marine transport. In this sense, the maintenance of reliable sea lanes should be viewed as directly connected with a nation's interests. This task is roughly equivalent to maintaining clear sea lines of communication, or SLOC, including ensuring that choke points are not closed off. Northeast Asia's main trading nations, namely, Japan, China, and South Korea, are particularly interested in sea lanes, both as coastal states and as states whose vessels pass through other states' waters. While this is clearly a matter of their maritime interests, we can also consider it as something connected to security concerns. Anything preventing maintenance of safe sea lanes--which need not involve anything so drastic as a military emergency--could harm these nations' economic activities, the foundation of all their activities as states. This makes these maritime issues nothing other than matters of national security.

Not only commercial vessels enjoy freedom of navigation; military vessels are also free to pass through other states' EEZs. In the case of military vessels, though, it can be difficult to tell just by observing them whether they are simply passing through an area or whether they are carrying out a survey, collecting intelligence, taking part in training exercises, or engaging in a military operation. UNCLOS recognizes the fundamental freedom of conventional use of the high seas, but the document does not clearly stipulate total freedom to carry out all actions in an EEZ that fall outside the purview of the coastal state's sovereign rights and jurisdiction. When India and six other nations signed and ratified UNCLOS, they included in their declarations demands that other states seek permission for all military exercises in their EEZs. China and several other states thereafter followed suit. These moves aimed to restrict acts by other nations' military vessels that could represent a threat to the coastal states in their own EEZs.

As coastal states also have jurisdiction within their EEZs regarding scientific surveys, environmental preservation, and construction of installations, some of these states have come to manage and control these seas in accordance with domestic laws, going well beyond the scope of control spelled out in UNCLOS. As one likely result of this, coastal states will increasingly seek to exercise their jurisdiction from the perspective of security.

5. Geopolitical Considerations of the Senkakus

Building on the above, I will finally turn to my consideration of the Senkaku Islands in geopolitical terms, dividing this into the two areas of natural resource exploitation, a core part of a coastal state's maritime interests, and security.

(1) Natural resource exploitation

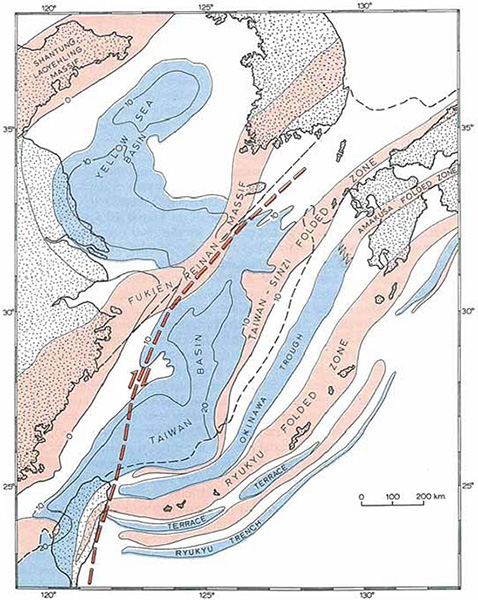

In the early 1970s, Taiwan and China began claiming sovereignty over the Senkakus, something they had not done until that point. This was in response to a 1969 report published by the United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East, or ECAFE, on a 1968 marine survey that found potentially huge reserves of oil and natural gas under the continental shelf in the East China Sea, particularly in the area north of Taiwan.3 The survey focused on hydrographic conditions, sea floor formations, and strata beneath the sea floor in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea; the report encapsulates its findings in the chart included here as Figure 3, stating the following on page 39:

"Most important for the oil and gas potential in the region is the sediment fill beneath the continental shelf and the Yellow Sea. . . . The most favorable part of the region for oil and gas is the 200,000 sq. km area mostly northeast of Taiwan. Sedimentary thicknesses exceed 2 km, and on Taiwan they reach 9 km, including 5 km of Neogene sediment."

If these findings are correct, the Senkaku Islands lie in an area containing massive reserves of oil. The ECAFE survey report was clearly the trigger for Taiwan's and China's sudden 1971 claims to the Senkakus--situated on the continental shelf to the north of Taiwan, west of the Okinawa Trough. Having said that, I will not address the reasoning and explanations behind the Chinese territorial claims in this paper.

Figure 3: Ridges, troughs, basins, and trenches in the East China Sea

- Source: ECAFE Committee for Co-ordination of Joint Prospecting for Mineral Resources in Asian Offshore Areas, "Geological Structure and Some Water Characteristics of the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea," Technical Bulletin vol. 2 (1969), p.40, available at https://www.gsj.jp/data/ccop-bull/2-01.pdf.

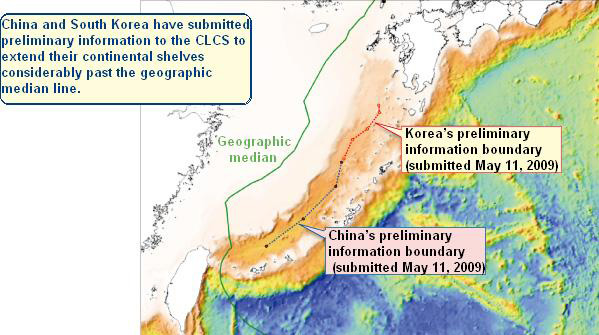

The exploitation of natural resources on the continental shelf is a sovereign right of the coastal state in control of the EEZ in question, making the territorial status of the Senkaku Islands immensely important. Figure 4 depicts the boundary line claimed by Japan on the basis of the Senkakus and the boundary at the Okinawa Trough claimed by China as the extent of its EEZ. The latter would carve out for China a considerable swath of the seas included in an EEZ based on Chinese sovereignty over the Senkakus, producing a major difference in the potential for exploitation of biological and nonbiological natural resources.

Figure 4: Japanese and Chinese continental shelf boundary claims

Source: Japan Coast Guard Annual Report 2010.

In the area of fishery resources, the fish and shellfish that inhabit the sea floor can be defined as a resource associated with the continental shelf. Ordinary fish, though, are held to be a resource located within an EEZ. China has not to date put forth a clear presentation of its EEZ-related claims, but the territorial status of the Senkaku Islands is plainly a key factor in deciding the boundaries of the coastal states' respective zones.

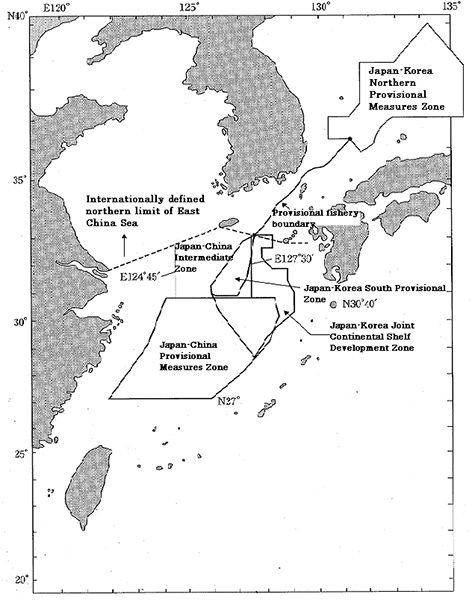

In 1997 Tokyo and Beijing signed the Japan-China Fishery Agreement, which went into effect in 2000. This agreement stipulates that in the waters around the Senkakus south of the 27th parallel, neither nation will interfere in the other's fishing activities in either side's EEZ.4 The agreement thus treats these waters as a contested area or an area where EEZs are as yet undefined.

In the waters north of the 27th parallel, an area claimed by both states has been designated as the Japan-China Provisional Measures Zone (see Figure 5). In this zone neither side can crack down on fishers from the other state. There is, however, a fishery committee in place to define permitted operations; when fishers commit infractions against these regulations, the states are able to issue warnings and notifications.5

Figure 5: Provisional Measures Zones and other zones

- Source: Shimada Yukio and Hayashi Moritaka, Kaiyo ho tekisutobukku (A Textbook on Maritime Law) (Tokyo: Yushindo, 2005).

We can thus see that a certain sagacity has been brought to bear in the area of fishery operations in the East China Sea: a solution that considers the positions of both China and Japan which maintains that no territorial dispute exists between it and China over these islands.

(2) Security issues

With respect to the freedom of navigation and freedom of use of the seas, we should note that neither Japan nor China will see problems in the area of commercial shipping depending on the territorial status of the Senkaku Islands. Should a military situation arise, of course, the possession of island territories will be key to the security of coastal states, as I will describe below, with these islands potentially being a factor restricting the passage of shipping vessels.

As I noted earlier, the interpretation and application of UNCLOS are in some respects unclear when it comes to the freedoms of navigation and use of the seas. There may also be cases where a coastal state, with its eye on its own security, seeks to restrict the actions of other states in its EEZ--particularly the actions of their military vessels. China has taken this security-related stance in repeatedly interfering with US naval survey vessels and intelligence-gathering aircraft operating in the EEZ it claims (or at least in the area immediately outside its territorial sea or its contiguous sea). It has also consistently responded with disapproval to American military exercises and other special operations by US vessels in its EEZ. All of these acts show a China willing to restrict the actions of other states in its EEZ with the aim of maintaining its own security.

If China claims these rights and undertakes these actions as a coastal state within its own EEZ, it will be forced to endure similar restrictions on its actions as a noncoastal state in the Japanese EEZ. Japan, however, guarantees the freedom of navigation and use of the seas in its EEZ, in line with the stipulations of UNCLOS. Japan does, of course, require prior notification for scientific research in this area (for which consent is in principle given in line with UNCLOS); it also reserves the rights to allow or disallow natural resource exploration surveys and to carry out surveillance of any military-related surveys or military activities in its EEZ.

The EEZ taking the Senkaku Islands as a baseline lies on the western side of the waters between Miyakojima Island and Okinawa connecting the East China Sea to the Pacific Ocean. When warships and other naval vessels pass through these waters they are subject to a variety of checks by Japan. In recent years numerous Chinese warships have made their way through this area to carry out exercises or military duties in the Western Pacific. As Japan places no specific restrictions on the actions of noncoastal states' naval vessels in its EEZ, the responses of Japan and China to these cases as coastal states are unsymmetrical.

Should Japan lose sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands, however, China would gain considerable freedom for its naval activities in these waters. Japan's Maritime Self-Defense Force, meanwhile, would find itself subject to major restrictions on its activities there due to China's stance on its EEZ. The impact on the United States, Japan's ally, would be even greater.

The same situation would arise in the skies over the EEZ, affecting aircraft in basically the same way. The skies are subject to a system of air defense identification zones separate from the classifications applied to sea areas, and sovereignty over island territories is a major factor impacting these zones.

Amid the tense situation surrounding the Senkakus that we saw in September 2012, China presented nautical charts to the United Nations defining its territorial sea from the baseline of those islands. As was reported in the September 17 Yomiuri Shimbun, China also announced that it would apply to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf for an extension of its shelf in the East China Sea. As noted above, Japan and China have to date adopted a policy of noninterference with each other's fishing activities in the EEZ around the Senkaku Islands. Moving forward, though, there is a high probability that the Chinese will ramp up its assertion of sovereign rights in the EEZ it claims (which overlaps considerably with that claimed by Japan) and its continental shelf, including the extended portion it is staking out as its own. It will also likely seek to hamper the military and other maritime activities of other countries--namely Japan and the United States--in its EEZ.

Above I have largely considered the geopolitical situation in terms of maritime activities. The question of whether islands are a nation's territory or not, though, decides whether that nation can make use of those islands at all, making it a vitally important issue from the security standpoint. If islands do belong to a nation, they can become the site of missile batteries, for instance, in either an offensive or defensive role. If another country holds those islands, however, it can use them to establish military facilities.

In 1962, at the height of the Cold War, the Soviet Union tried to station missiles in Cuba, just south of the continental United States. This touched off the Cuban Missile Crisis, a military situation that could easily have led to nuclear war. If the Senkaku Islands were to become Chinese territory, Okinawa--and Japan as a whole--could face a serious problem indeed.

6. Conclusion

In closing, I would note that no consideration of these issues can ignore the question of Taiwan. Indeed, if we view the Senkaku Islands in terms of their history or the circumstances, it is clearly Taiwan, not continental China, that we should be considering primarily as a relevant party. This being the case, it is Japan's relationship with Taiwan that is the key to issues from exploitation of biological and nonbiological resources to security. As things stand now, Taiwan's interest in the Senkaku Islands has reached the point where territorial rights can no longer be kept out of the picture, but originally the Taiwanese were interested mainly in maintaining the fishing rights they had traditionally held in the waters near the Senkakus. When it comes to security matters, it makes a considerable difference whether Japan is dealing with Taiwan or China as a counterparty.

Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou has stated that Taiwan has no intention of presenting a united front with China on the Senkakus issue. It is to be noted that he has called for a peaceful settlement of all disputes in the East China Sea among Taiwan, Japan, and China.6 We can achieve a clearer understanding of the geopolitical issues related to the Senkaku Islands by giving proper consideration to the Taiwan factor.

Recommended citation: Akiyama Masahiro, "Geopolitical Considerations of the Senkaku Islands," Review of Island Studies, August 7, 2013, /islandstudies//research/a00007/. Translated from "Senkaku Shoto ni kansuru chiseigaku teki kosatsu," Tosho Kenkyu Journal, Vol. 2 No. 1 (October 2012), pp. 28-39; published by the OPRF Center for Island Studies.

- Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou visited Pengjiayu on September 9, 2012, using the event to declare his desire for a peaceful settlement to the Senkaku Islands issue. [↩]

- See Figure 3. Japan of course does not recognize this claim. In terms of marine geography, the Okinawa Trough does not indicate the edge of the continental shelf, but is rather a simple depression on top of the shelf; Japan's argument is that the boundary between the two countries lies on that shelf, equidistant from them both. [↩]

- "Geological Structure and Some Water Characteristics of the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea," Technical Bulletin vol. 2, ECAFE Committee for Co-ordination of Joint Prospecting for Mineral Resources in Asian Offshore Areas. [↩]

- This is set forth in Article 6(b) of the agreement and in separate notes addressing these waters (issued by both the Japanese and Chinese sides). [↩]

- These provisions are in Article 6(a), Article 7 Paragraph 3, and Article 11 of the bilateral fishery agreement. [↩]

- On August 5, 2012, President Ma proposed the East China Sea Peace Initiative; on September 7 he announced the implementation guidelines available at http://english.president.gov.tw/Default.aspx?tabid=491&itemid=28074 (accessed on March 5, 2013). [↩]

RSS

RSS