Introduction

India has had territorial disputes with China over their Himalayan border for many years and in June 2020 clashes between the armies of the two countries occurred in the Galwan Valley along the Himalayan border, exacerbating the confrontation between them. On the other hand, India is still importing many industrial products from China even now. Excessive dependence on China’s technologies and components in strategic fields has become a source of security concerns.

In India, currently, electricity demand is expanding rapidly, and the introduction of renewable energy technologies has become essential to cover that demand. However, the current situation is that India depends on China for many of the major components and materials which support renewable energy power generation. As a result, India’s power supply, which is core national infrastructure, is becoming structurally vulnerable to China, a country which it is confronting over territorial disputes. For this reason, India is accelerating its initiatives to reduce its dependence on China, with the introduction of domestic production of renewable energy components as an important policy issue.

In this paper, we discuss the actual state of India’s dependence on China in its renewable energy industry from two perspectives: the status of imports of Chinese-made renewable energy components, and collaboration between Indian companies and Chinese companies in the Middle Eastern market. Furthermore, we consider the future outlook for introducing domestic production aimed at ending dependence on China.

India Is Advancing the Introduction of Renewable Energy

India is facing the urgent issue of meeting its ballooning electricity demand. Electricity generation increased greatly from 1,258 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2014 to 2,030 TWh in 2024, reaching a 4.9% average growth rate per annum over that period.[1] Factors behind this include the increase in the population, the expansion of industry, and the surging demand for air conditioning due to heat waves. The government of India believes that the building of new power plants is an urgent task for meeting this increase in demand, and it is strongly promoting the introduction of renewable energy such as solar and wind power.

The government of India’s first aim in promoting the widespread adoption of renewable energy is to reduce its dependence on imports of fossil fuels. India produces power-generating fuels such as coal and natural gas domestically to some extent, but as a consequence of the expansion of the size of its economy its energy consumption has soared, forcing it to rely on imports to cover the shortfall. In this context, with a surge in international resource prices, import costs could put a strain on the country’s finances, negatively impacting the economy as a whole. For that reason, the importance of renewable energy expansion is growing for the purposes of securing a stable long-term electricity supply and keeping down power generation costs. Next, the widespread adoption of renewable energy which does not emit carbon dioxide is highly consistent with India’s environmental countermeasures. In 2021, Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared for the first time that India would achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2070. Furthermore, the early introduction of solar and wind power, which are forms of clean energy, has become essential for measures to combat worsening air pollution, particularly in urban areas.

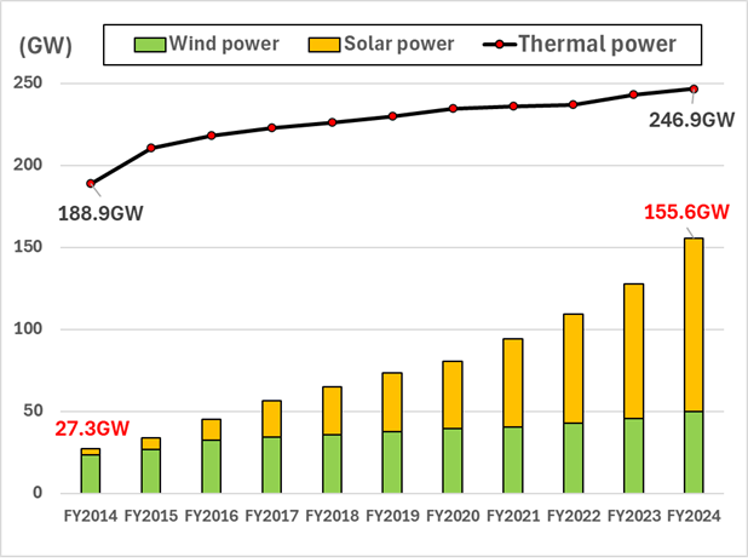

In recent years, the capacity of solar and wind power generation facilities in India has been approaching that of its main source of power, thermal power generation. In the ten years from fiscal year 2014/15 (April 2014 to March 2015), India’s solar power generation and wind power generation have greatly expanded from 3.9 gigawatts (GW) to 105.6 GW and from 23.4 GW to 50 GW, respectively. As of March 2025, the capacity of India’s solar and wind power generation facilities reached 155.6 GW (approximately 33% of the capacity of all power generation facilities in India; Figure 1), the second highest capacity after thermal power generation (246.9 GW, approximately 52% of India’s total capacity).

Looking at the installed capacity by state, Rajasthan (33.4 GW), Gujarat (31.1 GW), Tamil Nadu (21.8 GW), Karnataka (17.0 GW), and Maharashtra (15.9 GW) stand out. The capacity of the power generation facilities of these five states (approximately 120 GW) accounts for approximately 76% of India’s entire capacity. In Rajasthan and Gujarat in particular, geographical advantages, such as abundant sunshine in their desert regions and favorable wind conditions along the coast, combined with unique state initiatives, have contributed to the widespread adoption of renewable energy. For example, the introduction of “green budgeting” that makes sustainable financing possible and the “green tariffs” mechanism enabling the procurement of electricity derived from renewable energy at a fixed price over the long term play important roles in the promotion of projects in both states.[2]

Figure 1. Installed capacity of solar, wind, and thermal power generation in India (FY 2014–FY 2024)

However, solar power generation is normally limited to operation during the daytime under clear skies, and wind power generation is also greatly affected by the strength of the wind, so it is difficult to adjust the amount of power generation by these sources. As a result, there is the apparent drawback that the electricity supply to the transmission grid tends to be unstable depending on the time of day and weather conditions. Furthermore, although solar power generation is effective during daytime hours when demand for air conditioning is high, issues remain in meeting the demands of sectors that require an electricity supply at night, such as data centers and the AI industry, both of which are expected to expand rapidly in India going forward.

In this context, it is possible to build a structure which can supply solar-derived clean electricity 24 hours a day by utilizing electricity storage technologies such as the battery energy storage system (BESS). India is also rapidly advancing a plan to introduce BESS in conjunction with renewable energy power generation, and the expansion of the electricity storage market is gaining momentum.[4] According to the National Electricity Plan (NEP) announced by India’s Central Electricity Authority (CEA) in 2023, India’s domestic BESS demand is expected to grow from 8.6 GW on an output basis and 34.7 GWh on a capacity basis in fiscal year 2026/27 to 47.2 GW and 236.2 GWh, respectively, in fiscal year 2031/32.[5]

India’s Dependence on China in the Renewable Energy Industry

On the other hand, the more actively India introduces renewable energy and energy storage facilities, the greater its dependence on China, a country which it is confronting over territorial disputes, is likely to become. That is because China has an overwhelming share and influence in the global renewable energy market. China’s renewable energy companies are reducing costs using large-scale mass production structures inside China and at the same time they are incorporating and improving technologies sourced from Europe, thereby reaching a level that is sufficiently competitive with Western companies. Furthermore, China has built a strong global supply chain centered on the country by gaining control over the critical minerals (such as copper, lithium, graphite, cobalt, and others) essential for renewable energy and BESS products on a global scale, and combining this approach with its mineral resources refining and processing technologies.[6] Moreover, by applying the technologies and know-how cultivated in the development of batteries for electric vehicles (EVs) to BESS as well, Chinese companies (BYD, CATL, Sungrow, and others) have established strong positions as world-leading suppliers in the electricity storage market as well. For these reasons, India is forced to rely on China to secure the major components necessary for solar power generation, wind power generation, and BESS.

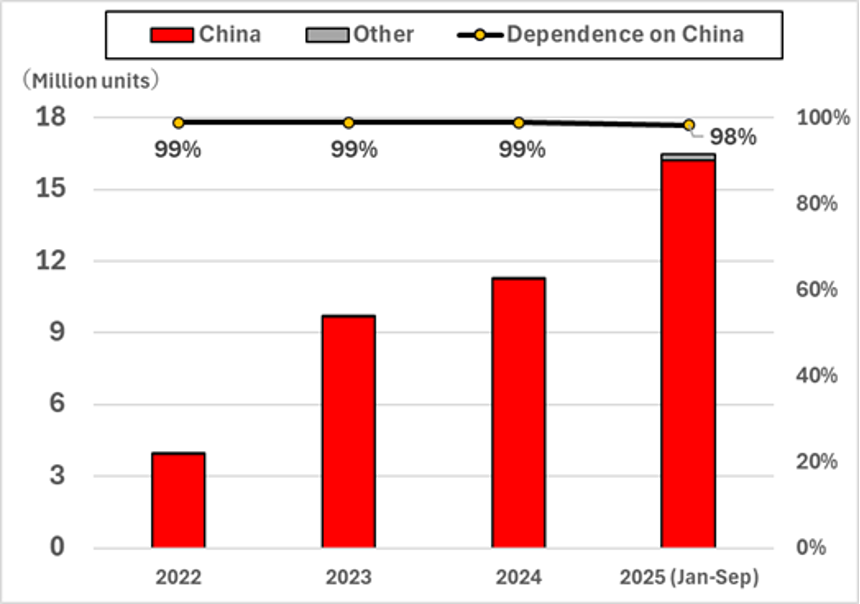

Actually, trade statistics also confirm that the majority of the solar components procured by India are products imported from China. Firstly, imports of silicon semiconductor substrate “wafers,” which form the substrates of solar cells, increased from approximately 3.5 million wafers in 2022 to approximately 11 million wafers in 2024, and in 2025 imports of approximately 16 million wafers have been recorded in just nine months. In parallel with this expansion of imports, the imports from China have accounted for nearly 100% of the total imports (Figure 2), so India’s dependence on China has been trending at an extremely high level.

Figure 2. India’s wafer import partner countries (2022–September 2025)

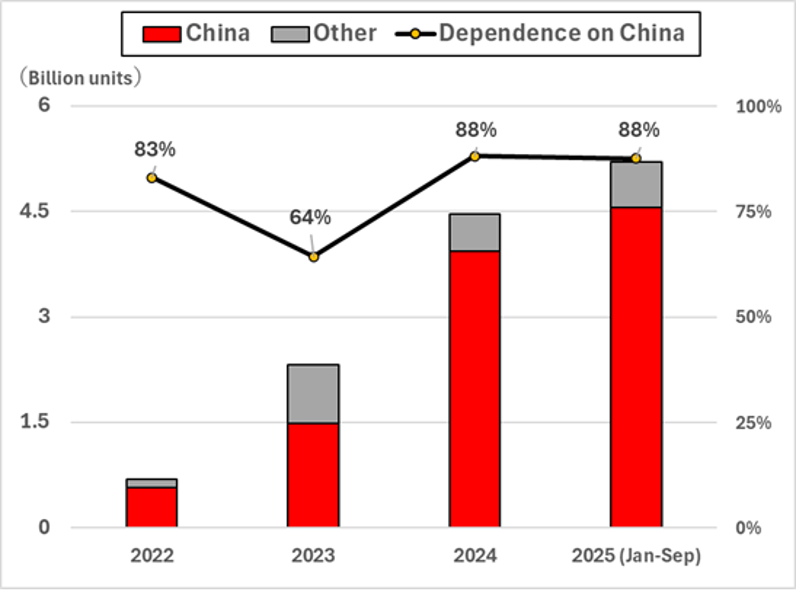

Next, regarding cells, which have the function of converting sunlight into electricity through wafer processing, imports from China increased from approximately 600 million cells in 2022 to approximately 4.6 billion cells from January to September 2025, and as a result dependence on China reached nearly 90% (Figure 3).

Figure 3. India’s cell import partner countries (2022–September 2025)

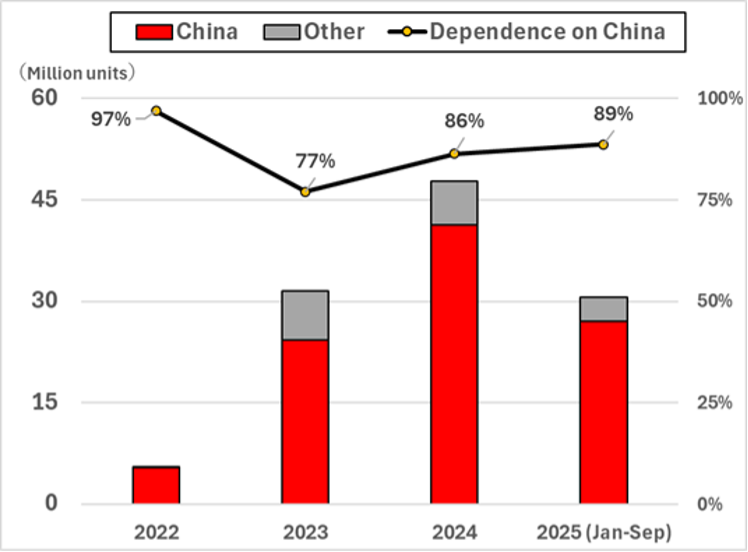

Moreover, India’s dependence on China remains at the high level of over 85% for “modules,” the completed solar panels in which multiple cells are connected in series and in parallel (Figure 4). Concerning cells and modules, imports from countries other than China account for approximately 10% of the total imports, but Chinese companies are substantially involved in many of those imports as well. The background to this is that the government of India imposed customs duties of 40% on modules and 25% on cells in April 2022 with the objectives of encouraging the introduction of domestic production and reducing imports of Chinese-made products. [7] In response to this, Chinese companies (Jinko Solar, LONGi, Trina Solar, JA Solar, Risen Energy, and others) have used free trade agreements (FTAs) between India and Southeast Asian countries as a springboard for roundabout trade, exporting products to India via third countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Laos, Cambodia, and others in an attempt to avoid the high customs duties.

Figure 4. India’s module import partner countries (2022–September 2025)

Even more noteworthy is the fact that India and China are cooperating in a mutually complementary way in the overseas renewable energy market. In particular, even when India’s leading construction companies (Sterling & Wilson, Larsen & Toubro, and others) win engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contracts through competitive bidding in large-scale solar projects in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), many of the solar components for the projects are procured from Chinese companies.[8] By combining India’s low-cost labor force and track record in large-scale construction with China’s inexpensive, mass-suppliable renewable energy components in this way, Indian companies successfully achieve price competitiveness superior to that of their competitors in other countries. We can conclude that this kind of approach is symbolic of a mutually-beneficial cooperative structure taking advantage of the strengths of both India and China.

The Future Outlook for the Shift to Domestic Production, Which Holds the Key to Ending Dependence on China

The concept of “economic independence” has been firmly established in India for many years. The swadeshi economic movement (meaning “from one’s own country” in Hindi) which emerged at the beginning of the 20th century called for the promotion of self-sufficiency, reduction in dependence on overseas products, and a shift away from British products. Prime Minister Modi launched the Make in India program in a form which inherited this philosophy when he came to power in 2014, in order to promote the development of domestic manufacturing with a focus on the defense industry, while also attracting foreign investment. In March 2020, Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes were introduced, providing subsidies to boost the introduction of domestic production of strategic goods such as cell phones, electronic components, and medical devices. Moreover, in May the same year, Prime Minister Modi set out the Atmanirbhar Bharat (self-reliant India) concept, and launched a policy of further increasing the self-sufficiency of the Indian economy through the strengthening of domestic production capacities.[9]

In accordance with this self-reliant India concept, the government of India has also worked on the introduction of domestic production in the renewable energy industry. As an example of an outcome from this policy, in August 2025, it was announced that the solar PV module manufacturing capacity of India had expanded from 2.3 GW in 2014 to 100 GW.[10] In addition, India has started to build a supply network for critical minerals. For example, it has begun increasing production of neodymium, one of the rare earths essential for wind power turbine manufacturing.[11]

However, although the introduction of domestic production for final products such as modules and cells is progressing steadily, the materials used to make those products (wafers, polysilicon, ingots) are still dependent on China, so the complete introduction of domestic production is still a long way off. Furthermore, Indian-made modules and cells are more expensive than Chinese-made ones at the current time, [12] raising concerns that the introduction of domestically produced products will lead to rising power generation costs. Moreover, if Indian construction companies insist on using domestically produced components even in competitive bidding in overseas renewable energy markets, they will highly likely be at a disadvantage, with their price competitiveness declining compared to competitors in other countries that employ lower-priced Chinese-made components. In addition, even if India develops critical minerals such as rare earths, it has not sufficiently developed its refining and processing capabilities, so building an integrated supply chain like China’s will take a long time.

Given this situation, even though India is in a confrontation with China over territorial disputes, India will likely be forced to maintain a dependency relationship with China to some extent in the renewable energy industry, in order to ensure a stable electricity supply and keep down economic costs. As a result, even though India has set out a long-term vision of ending dependance on China, it can be concluded that the cooperative relationship between India and China, which is based on practical benefits, will continue for the time being.

(2026/01/06)

Notes

- 1 “Statistical Review of World Energy 2025,” Energy Institute, June 2025, p. 53.

- 2 Tanya Rana and Vibhuti Garg, “Cementing Rajasthan’s and Gujarat’s Renewable Energy Leadership,” Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, October 2024.

- 3 “Renewable Energy Statistics 2024-25,” Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, November 2025, pp. 10-14.

- 4 From 2022 to May 2025, India auctioned approximately 12.8 GWh of battery energy storage system (BESS) capacity. Charith Konda, “India’s Battery Storage Boom: Getting the Execution Right,” Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, August 18, 2025.

- 5 “National Electricity Plan 2023,” Central Electricity Authority of India, March 2023, p. lxii.

- 6 Masahide Takahashi, “China’s Clean Energy Policy: Why China Will Push for Clean Energy Despite the Trump Administration’s Withdrawal from the Paris Agreement,” International Information Network Analysis (IINA), February 25, 2025.

- 7 Vinod Mahanta, “Import of cheaper solar modules on rise as China exploits loopholes,” The Economic Times, December 7, 2023.

- 8 For the Noor Abu Dhabi Solar Power Plant project in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, UAE, Sterling & Wilson of India was in charge of the construction and Jinko Solar of China supplied the modules. Furthermore, for the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum (MBR) Solar Park Phase 6 project in the Emirate of Dubai, Larsen & Toubro of India is advancing the construction and Astronergy of China is providing the modules. In Saudi Arabia as well, for the Jeddah Solar Power Plant and Sudair Solar Power Plant projects, Larsen & Toubro of India worked on the construction and LONGi of China supplied the modules. For example, “LONGi to Supply Larsen & Toubro with Modules for Projects in Saudi Arabia,” LONGi News, November 29, 2022.

- 9 Sylvia Malinbaum, “India’s Quest for Economic Emancipation from China,” Institut français des relations internationales, January 23, 2025, pp. 19-20.

- 10 “India Achieves Historic Milestone of 100 GW Solar PV Module Manufacturing Capacity under ALMM,” Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, August 13, 2025.

- 11 Koustav Das, “Race for the rare earths: Why India is tripling its magnet bet,” India Today, November 4, 2025.

- 12 For example, the price of Indian-made modules is 0.18 dollars per watt-peak (Wp), which is high compared to the 0.1 dollars per Wp of Chinese-made modules. Dhruv Warrior et al., “Strengthening India’s Clean Energy Supply Chains: Building Manufacturing Competitiveness in a Globally Fragmented Market,” Council on Energy, Environment and Water, September 16, 2024, p. 35.