The accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station following the Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, 2011, marked a major turning point in Japan’s energy policy. Since then, nuclear power generation has stalled. Coal and natural gas-fired power plants have played a central role in maintaining a stable electricity supply. Against this backdrop, Australia has provided a stable supply of fuels necessary for Japan’s thermal power generation. At the same time, challenges related to coal development and natural gas exports are emerging in Australia.

This paper examines trends in Japan’s electricity supply since 2011, the role of Australia as a major supplier of fuel for thermal power generation, and whether Australia’s resource development challenges will affect Japan’s energy supply.

Japan’s Electricity Supply Following the Nuclear Accident

The accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station sharply increased public concern and suspicion regarding the safety of nuclear power in Japan. Previously, reactors were promptly restarted once their safety was confirmed through periodic inspections, which are required every 13 months under the Electricity Business Act. Following the disaster, however, reactors remained offline even after inspections were completed. In May 2012, when Unit 3 of the Tomari Nuclear Power Station was shut down for routine maintenance, all operational reactors in the country came to a temporary standstill.

In response to the accident, Japan restructured its nuclear regulatory system. To separate the promotion of nuclear energy from its oversight and to strengthen independent safety regulation, the Nuclear Regulation Authority was established in September 2012 as an affiliated agency of the Ministry of the Environment.[1] Under the new framework, reactors were required to meet new regulatory standards before they could restart. This made the restart of reactors even more difficult. In addition, to ensure public health and safety, operators must obtain consent from local governments (prefectures and municipalities) before restarting operations. These requirements are outlined in safety agreements that mandate reporting systems, on-site inspections, and prior consultations for any facility expansions.[2]

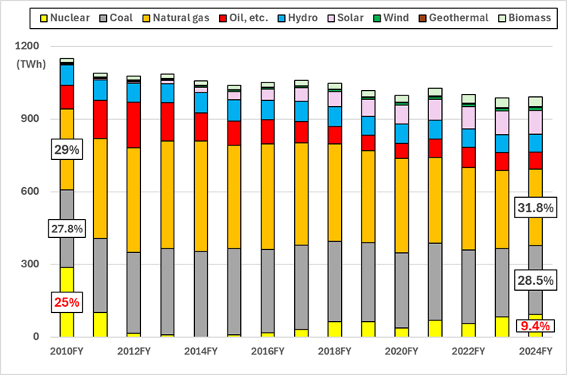

At the end of 2010, Japan had the world’s third-largest nuclear power generation capacity after the United States and France, with 54 reactors in operation.[3] However, the shutdown of all reactors caused nuclear power generation to plummet from 288.2 terawatt-hours (TWh) in fiscal year 2010 to zero by fiscal year 2014. Although some reactors have restarted since FY 2015, the share of nuclear power in total generation has continued to remain at a level below 10% (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Japan’s Electricity Generation by Source (FY 2010-2024)

Since 2015, progress has been made in restarting nuclear power plants, particularly in western Japan. Kyushu Electric Power Company restarted the Sendai Nuclear Power Station in 2015 and resumed operations at the Genkai Nuclear Power Station in 2018. Since 2016, Kansai Electric Power Company (KEPCO) has also phased in restarts for several units, including Mihama Unit 3, Ohi Units 3 and 4, and Takahama Units 1 through 4. Additionally, Shikoku Electric Power Company restarted Ikata Unit 3 in 2016, and Chugoku Electric Power Company began restarting Shimane Unit 2 in December 2024.[5]

In contrast to western Japan, restarts have been delayed overall in eastern Japan, where Boiling Water Reactors (BWR), the same type as those at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, are widely used. Restarts here have been hindered by a cautious approach from Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings (TEPCO) because of its role in the Fukushima Daiichi accident, as well as the difficulty of securing consent from local municipalities. The only successful restart in eastern Japan to date is Onagawa Unit 2 in Miyagi Prefecture, which resumed operations in 2024.

Recent developments suggest a slight shift. In November 2025, Governor Hideyo Hanazumi of Niigata Prefecture approved the restart of Units 6 and 7 at the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Station. Consequently, TEPCO restarted Unit 6 on January 21, 2026, for the first time in 14 years, though the reactor was subsequently halted due to an alarm during control rod withdrawal operations. Commercial operation of Unit 7 is expected to begin during 2026. Furthermore, in December 2025, Governor Naomichi Suzuki expressed his approval for the restart of Tomari Unit 3.

While restarts have made gradual progress, Japan’s nuclear sector faces the dual challenges of decommissioning and operating life extension. Since the nuclear accident, some existing reactors have had their decommissioning decided without ever being restarted. These include all units at Fukushima Daiichi and Fukushima Daini, as well as Onagawa Unit 1, Tsuruga Unit 1, Mihama Units 1 and 2, Ohi Units 1 and 2, Shimane Unit 1, Ikata Units 1 and 2, and Genkai Units 1 and 2. A total of 21 reactors have been designated for decommissioning. Their combined generating capacity is approximately 15 gigawatts (GW), equivalent to roughly 30% of the total nuclear capacity operating at the time of the 2011 disaster.[6] Even if the 19 reactors that are currently idled were gradually restarted, nuclear generation would not return to its FY 2010 level of 288.2 terawatt-hours (TWh).

Aging infrastructure presents an additional concern. Of the 33 reactors considered operable, about 40%, or 14 units, were built in the 1970s and 1980s and roughly 40 years have passed since they began operation. In principle, reactors are licensed to operate for 40 years. However, a system introduced in 2023 allows extensions of up to 20 additional years with the approval of the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry.[7] However, this measure merely postpones the decision on decommissioning, and each reactor will ultimately have to cease operations in the future.

Australia: A Major Supplier of Fuel for Thermal Power Generation

The sharp decline in nuclear energy utilization has led to a significant reliance on coal and gas-fired power generation. Thermal power remains Japan’s main source of electricity. In FY 2024, coal-fired power accounted for 28.5% of total generation, while gas-fired power accounted for 31.8%. This continued dependence on thermal power reflects the current situation where it is unlikely that new nuclear power construction projects will make full-scale progress. At present, only three reactors are under construction: Ohma, Higashidori and Shimane Unit 3. In addition, Kansai Electric Power announced in November 2025 that it had begun geological surveys aimed at building a next-generation nuclear reactor. However, no specific construction plan or completion date has been set.

Solar power has expanded significantly as an alternative to nuclear energy, growing from 3.5 TWh in FY 2010 to 98.1 TWh in FY 2024. However, solar power can only operate during sunny daylight hours, making it difficult to adjust the amount of power generated. Given these constraints, Japan will need to maintain a certain level of thermal power generation to ensure a stable electricity supply.

Australia supports Japan’s procurement of coal and natural gas. Coal trade between the two countries expanded alongside Japan’s postwar industrial growth. Rising demand for steel led to large-scale coal mine development in Queensland, and exports of coking coal to Japan began in 1959. In 1963, Japanese companies participated for the first time in coal development projects in the state, providing financing and securing supply for the Japanese market. During the two oil crises in the 1970s, sharp increases in crude oil prices prompted a reassessment of the role of coal (thermal coal) as a power generation fuel to replace oil, leading to an increase in thermal coal exports from Australia.[8]

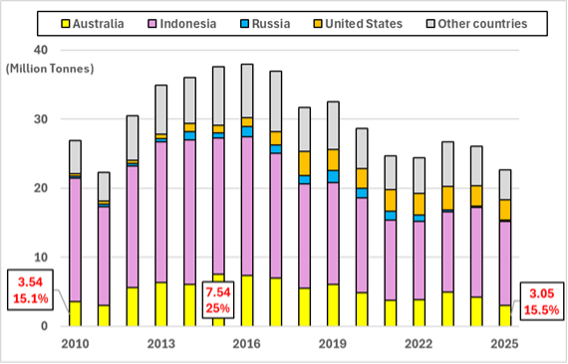

Today, Australia is the second-largest supplier of thermal coal to Japan. Imports rose from 3.54 million tons (15.1% of total imports) in 2010 to 7.54 million tons (25%) in 2015, due to an increased reliance on coal-fired power following the nuclear shutdowns after the Great East Japan Earthquake (Figure 2). Even according to the latest 2025 data, Australia provided 3.05 million tons (15.5%), confirming its status as a consistently essential partner for Japan’s coal-fired power generation.

Figure 2: Japan’s Thermal Coal Imports by Country (2010–2025)

Regarding natural gas imports, the North West Shelf (NWS) project in Western Australia launched the first liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports to Japan in 1989.[9] Since the 2000s, Japan has supported the development of the country’s natural gas industry by investing in LNG projects deployed across Australia and through long-term LNG purchase agreements.

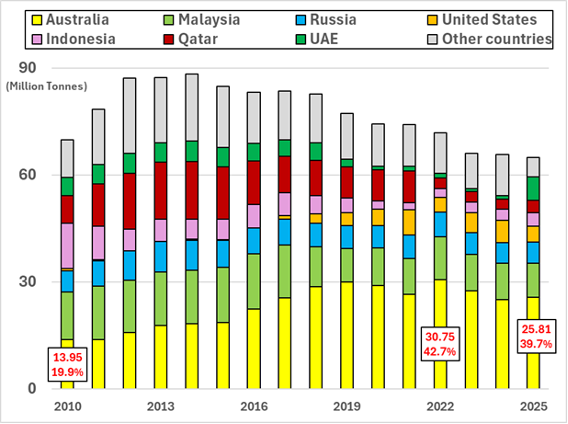

In the wake of the 2011 nuclear accident, Japan’s demand for LNG surged, making Australia a major LNG supplier to Japan. Imports rose from 13.95 million tons (19.9% of total imports) in 2010 to a record high of 30.75 million tons (42.7%) in 2022 (Figure 3). According to the latest 2025 data, Australia provided 25.81 million tons (39.7%), strengthening its presence as Japan’s most reliable energy supplier.

A notable feature of Japan’s engagement in Australia’s LNG sector is direct participation in upstream development. Rather than relying solely on purchase contracts, Japanese companies are involved from gas field development through LNG production. In the Ichthys LNG project offshore northwestern Australia, the Japanese energy company INPEX serves as the project operator, overseeing development and production. Building such a system for the independent development of natural gas by Japanese companies is extremely important from the perspective of energy security, centered on ensuring stable LNG supplies.

Furthermore, Japanese companies have boosted their revenues by reselling Australian LNG to third countries. Many Australian LNG contracts do not include destination clauses that prohibit resale, unlike many contracts for Qatari LNG. This flexibility allows Japanese companies to trade surplus volumes. As of 2025, annual contracted volumes of Australian LNG held by Japanese companies total 29.85 million tons, exceeding Japan’s actual import volume.[10] Through LNG trading of these surpluses, Japanese companies generated substantial profits, estimated between 11 billion and 14 billion Australian dollars in 2023.[11]

Figure 3: Japan’s LNG Imports by Country (2010–2025)

Resource Development Issues in Australia and Implications for Japan

Australia, now an indispensable partner in Japan’s energy strategy, faces several challenges in resource development. The first concerns the coal sector, which is under pressure from global decarbonization efforts. Among fossil fuels, coal produces more carbon dioxide (CO2), a principal driver of global warming, than oil or natural gas, and its high emission factor is being viewed as problematic. The Australian federal government has set a target of achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.[12] Based on this goal, most domestic coal-fired power plants are projected to be phased out by 2035.[13] This decline in demand, both at home and abroad, could reduce profitability, discourage new investment, and increase production costs as environmental regulations tighten, there is a risk that it will become difficult to continue coal projects.

As Australia’s position as a coal-exporting country begins to waver, it continues to pursue mine expansions and extensions of operating licenses for thermal coal projects. If proposed developments in New South Wales and Queensland proceed, thermal coal production capacity could increase by approximately 1.8 billion tons by 2050. Many of these large-scale mining projects are aimed at boosting exports.[14] As a result, even amid the global push toward decarbonization, Australia is seeking to maintain its role as a coal supplier through mine expansion and export capacity strengthening. In the near term, therefore, a significant disruption to Japan’s coal supply appears unlikely.

The second challenge is that the Australian federal government is strengthening its policy of prioritizing natural gas supply to the domestic market. In response to rising gas prices and concerns about domestic shortages, the Australian government has strengthened measures to ensure adequate supply for the domestic market. In Western Australia, the “Domestic Gas Policy” (DomGas Policy) has required LNG exporters to reserve 15% of their production for the state’s domestic market since 2006. In December 2025, the government announced plans for a “domestic gas reservation system” for the east coast, which will require exporters to supply between 15% and 25% of their production to the eastern region starting in 2027.

However, these domestic policies are unlikely to have an immediate impact on LNG projects involving Japanese companies. For example, Western Australia regulations do not apply to the INPEX-operated Ichthys LNG project because the liquefaction of natural gas is conducted in Darwin, the capital of the Northern Territory.[15] Furthermore, the new east coast regulations are expected to apply only to new contracts concluded after the policy takes effect, meaning existing agreements held by Japanese companies should remain unaffected.[16]

While Australia must address domestic concerns over rising energy prices, the nation places importance on its long-standing relationship of trust and track record of cooperation in the coal and LNG sectors with Japan. As a result, Australia is likely to maintain a stable and reliable energy supply framework for Japan.

(2026/02/18)

Notes

- 1 Ministry of the Environment, “2013 White Paper on the Environment, Sound Material-Cycle Society and Biodiversity,” June 28, 2013, p. 302.

- 2 Takuji Koike, “New Regulatory Standards and Restarting Nuclear Power Plants: Focusing on Issues Surrounding the Resumption of Operations at the Sendai Nuclear Power Station,” Research and Information, No. 840, Research and Legislative Reference Bureau, National Diet Library, January 2015, p. 9.

- 3 “Nuclear Power Reactors in the World 2011 Edition,” International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), June 2011, pp.10-11.

- 4 “Fiscal Year 2024 Energy Supply and Demand Results (Preliminary Report),” Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, December 12, 2025, p. 5.

- 5 “Recent Trends in Nuclear Energy,” Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, June 24, 2025, p. 3.

- 6 “Nuclear Reactors in Japan,” World Nuclear Association, accessed January 10, 2026.

- 7 Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, “Overview of the Approval System for Nuclear Power Plant Operating Life Extensions,” May 2025, p. 2.

- 8 Jun Yoshimura, “Changes in Major Players in Australia’s Coal Industry and the Pricing of Thermal Coal for Japan,” Energy Economics, Vol. 46, No. 2, Institute of Energy Economics, Japan, June 2020, p. 19.

- 9 “Major milestone,” Woodside Energy, June 28, 2019.

- 10 “Natural Gas and LNG Data Hub 2025,” Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security (JOGMEC), February 19, 2025, pp. 75–76.

- 11 Amandine Denis-Ryan and Josh Runciman, “How Japan cashes in on resales of Australian LNG at the expense of Australian gas users,” Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, May 20, 2025.

- 12 “Net Zero,” Australian Government, November 25, 2025.

- 13 “Australia’s Net Zero Transformation: Treasury Modelling and Analysis,” The Treasury of Australia, September 18, 2025, p. 18.

- 14 Anne-Louise Knight, “Australia pursues adding 1.8 billion tonnes of thermal coal despite declining market conditions,” Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, December 16, 2025.

- 15 “WA Domestic Gas Policy,” Government of Western Australia, August 4, 2025.

- 16 Byron Kaye and Emily Chow, “Australia forces LNG exporters to keep a minimum amount for home market,” Reuters, December 22, 2025.