Marine Scientific Research by Third Countries over the Extended Continental Shelf

Mar 22, 2020 PDF Download

Introduction

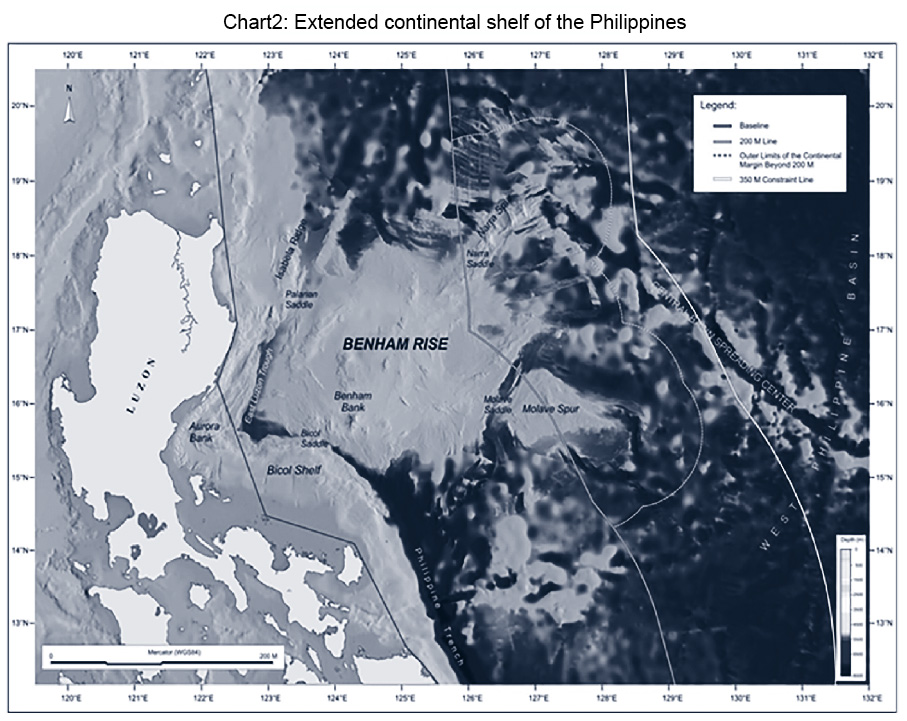

In March of 2017, a Chinese marine research ship was spotted that stayed in the water area over the Benham Rise off the eastern part of Luzon Island on the extended continental shelf of the Philippines[1]. It is not clear whether the ship was conducting marine scientific research. On March 10, in relation to this case, the Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs expressed concern about the existence of Chinese research ships often observed over the Benham Rise and issued a statement requesting that the Chinese government should explain about the circumstances under which such ships were sent to the water area[2]. In response to this statement, a spokesperson of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs said on the same day, when asked by a news reporter about the affair mentioned above, that the said vessel was just navigating in the water area and that it was not engaged in any other operations[3]. Since 2015, it had been reported that there were cases in which Chinese marine research ships were often observed in the same water area[4]. The Benham Rise constitutes the greater part of the extended continental shelf of the Philippines. It has been pointed out since early on that there may be large deposits of oil and natural gas under the Benham Rise, and the waters over the Benham Rise also have abundant marine living resources. For this reason, on April 8, 2009, in accordance with Article 76, paragraph 8 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and Annex II of the Convention, the Philippine government submitted information on the limits of the continental shelf to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) in order to exercise its sovereign rights to the Benham Rise as well as the 200-nautical-mile conventional continental shelf[5]. On April 12, 2012, CLCS made recommendation on the application of the Philippine government. On July 17 of the same year, following the recommendation, the Philippine government deposited charts and relevant information describing the outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles with the Secretary-General of the United Nations in accordance with Article 76, paragraph 9[6].

If it is assumed that the Chinese ship was carrying out marine scientific research on the Benham Rise, it follows that the research ship was on the high seas even if it was engaged in a survey of the extended continental shelf. Aren’t there fears that any problems arise from this situation under international law? The present paper examines this issue while analyzing discussions about this question.

Source: The outer edge of the continental margin in the Benham Rise Region, determined in accordance with the rules of Article 76 (4)(a)(i) of UNCLOS and the Scientific and Technical Guidelines of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf.[7]

1. Legal nature of the extended continental shelf

(1) Difference from the 200-nautical-mile continental shelf

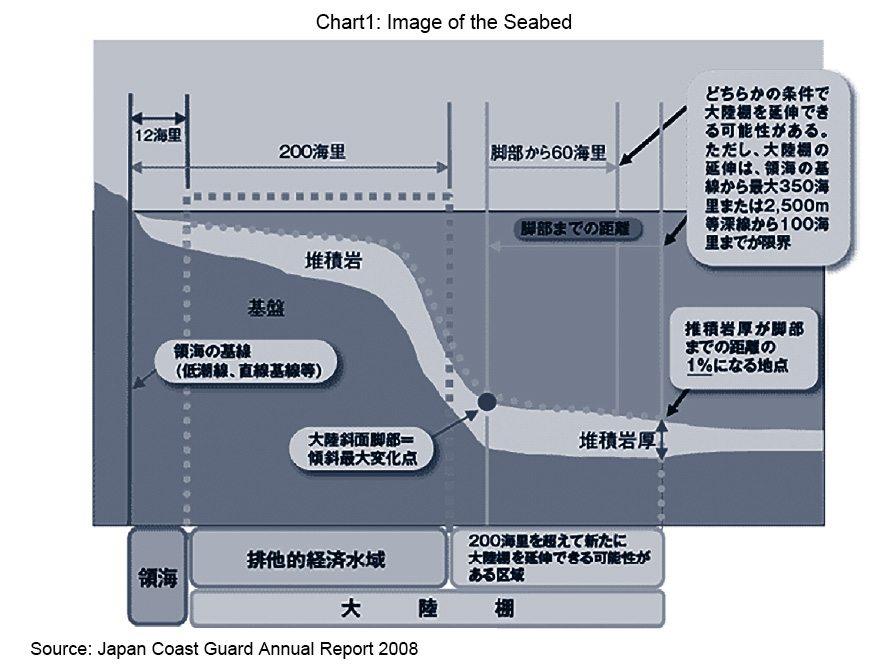

In the first place, the Benham Rise, which is taken up as an issue in this article, occupies the majority of the continental shelf of which the Philippine government applied for extension. If the basic points are organized for discussion, are there any differences between the legal nature of the 200-nautical-mile conventional continental shelf and the one beyond 200 nautical miles?Article 76 of the U.N. Convention of the Law of the Sea defines the continental shelf, stating that the continental shelf of a coastal State comprises the seabed and subsoil of the submarine areas that extend beyond its territorial sea throughout the natural prolongation of its land territory to the outer ridge of the continental margin. Therefore, if the continental margin continues beyond 200 nautical miles, the seabed concerned is interpreted as being considered as part of the State’s continental shelf. If based on this definition, however, only a particular state can establish a vast continental shelf if its continental margin stretches infinitely, and this is not fair. For this reason, limits are set for the range of continental shelves[8], and there are exceptions to such limits if, like the Bay of Bengal, the sea area concerned has a unique seabed[9].

From a geographical or geological point of view, there seems to be no basic difference between the 200-nautical-mile continental shelf and the one beyond 200 nautical miles. Aren’t there, then, any differences between the two from a legal point of view? Article 82 is frequently taken up when discussing the relationships between the two. The article obligates coastal States to pay or contribute through the International Seabed Authority (ISA) a certain percentage of volumes or amounts produced when exploiting non-living resources of the extended continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles, and ISA distributes them to member states on the basis of equitable sharing criteria. In other words, all profits earned from the exploitation of the 200-nautical-mile continental shelf belong to the coastal state concerned, but this does not apply to the extended continental shelf. This sometimes raises doubts about whether the two are of the same legal nature[10]. The article, however, is considered as reflecting a compromise between states which are concerned that the extension of the continental shelf causes the deep seabed to be decreased and those which claim continental shelves beyond it[11]. Furthermore, article 142 indicates that resources stretching over the extended continental shelf and the deep seabed beyond shall be explored and exploited by ISA while paying proper attention to the rights and legitimate interests of coastal States and that ISA is required to obtain the prior consent of the States. This suggests that the extended continental shelf is covered by the sovereign rights of coastal states[12]. In fact, in the dispute over the delimitation of maritime boundaries in the Bay of Bengal in 2012, the decision stated that there was no difference between the 200-nautial-mile continental shelf and the one beyond 200 nautical miles as stipulated in Article 77, Paragraphs 1 and 2 and that coastal states were allowed to exercise their sovereign rights over the entire continental shelf[13].

(2) Measures taken by the Philippine government for the extended continental shelf

The previous section analyzed the legal nature of the 200-nautical-mile continental shelf and the one beyond 200 nautical miles, and as a result, it became clear that notwithstanding the provisions of Article 82 in particular, there is no difference between the two. What action did the Philippine government take in this issue under international and domestic laws in order to claim its sovereign rights to the Benham Rise against other states, including China?Procedures for extending the continental shelf were mentioned at the beginning of the article but are summarized in this section again, including related provisions, as follows:

A state intending to extend its continental shelf should establish the outer limits of its extended continental shelf based on the recommendations made by CLCS, and the extended continental shelf thus established is final and binding. The point at issue here is whether the recommendations made by CLCS are legally binding under international law and what the establishment by a coastal state of the outer limits of its continental shelf means.Article 76, paragraph 8: “Information on the limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured shall be submitted by the costal State to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf… The Commission shall make recommendations to coastal States on matters related to the establishment of the outer limits of their continental shelf. The limits of the shelf established by a coastal State on the basis of these recommendations shall be final and binding.”

paragraph 9: “The coastal State shall deposit with the Secretary-General of the United Nations charts and relevant information, including geodetic data, permanently describing the outer limits of its continental shelf. The Secretary-General shall give due publicity thereto.”

Since early on, the predominant view has been negative toward whether the recommendations made by CLCS were legally binding[14]. One of the important bases for that is that the limits of the extended continental shelf are not confirmed by the recommendations of CLCS alone. But it cannot be said that these recommendations do not have any meaning. Paragraph 8 stipulates that the limits of the extended continental shelf shall be final and binding if they are established by the coastal State on the basis of CLCS’s recommendations. Worded differently, it is not obligatory to follow CLCS’s recommendations, but if they are followed, the limits of the shelf established on the basis thereof can be considered as effective as publicly authorized ones[15]. On the other hand, it is not necessarily clear what the establishment by a costal state of the limits of its extended continental shelf after CLCS’s recommendations means in concrete terms. In general, it is interpreted as meaning a declaration by the state, the enactment of its laws and ordinances, and so forth, but details are not certain.

With respect to this matter, the Philippine government received the recommendation from CLCS. But it is somewhat doubtful whether the government has established the limits of its continental shelf based on such recommendation. As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, after receiving the recommendations, the government deposited charts and relevant information describing the outer limits of its continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles with the U.N. Secretary-General in accordance with Article 76, paragraph 9[16], but as far as the author investigated, it does not seem that the government took measures related to the limits of the continental shelf---for example, the revision thereof---under domestic law. Even if the Philippine government has taken certain measures under domestic law, opinion is divided today about whether that prevents third countries from raising objections to the extended continental shelf claimed by the government[17]. Furthermore, some experts are of the opinion that if a third country disputes the legal status of the extended continental shelf, the provision that the established limits of the extended continental shelf are final and binding does not have a crucial meaning[18]. As described above, with respect to how to establish the limits of the extended continental shelf, many points are still left unclarified, and therefore, if a third country disputes the legal status of or raise objections to the established limits of an extended continental shelf, it would be necessary to give consideration to such disputes or objections separately. But the Chinese government’s response to the Philippines’ extended continental shelf is clear. The reason is that at the regular press conference held on March 14, a spokesperson of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs emphasized that China completely respected the Philippines’ sovereign rights over the Benham Rise and that it did not dispute them at all[19].

2. Marine research activities over the extended continental shelf and enforcement measures taken by coastal states

It is still somewhat unclear whether the Philippine government has established the limits of its extended continental shelf, but as long as the Chinese government has acknowledged the Philippines’ rights to the extended continental shelf, there is no doubt that Chinese government regards the extended continental shelf as the Philippines’ one. Therefore, the following section organizes some points disputed over marine scientific research over the extended continental shelf.(1) Draft history of Article 246, paragraph 6

Article 246, paragraph 2 stipulates that marine scientific research in the exclusive economic zone and on the continental shelf shall be conducted with the consent of the coastal State. In principle, however, coastal states must grant their consent if such research is conducted exclusively for peaceful purposes and in order to increase scientific knowledge of the marine environment for the benefit of all mankind[20]. In some cases, however, coastal states may withhold their consent at their discretion, and these four cases are prescribed in paragraph 5 of the same article. And then comes paragraph 6, which provides for extended continental shelves as follows:As their text shows, this provision should be interpreted as constituting an exception to paragraph 5. The characteristic of the provision is, above all, that whether costal states can grant their consent is determined by whether they do so inside or outside “those specific areas” which they may at any time publicly designate as areas… within a reasonable period of time. This is, however, largely attributed to the somewhat mysterious discussions held before paragraph 6 was added. It was in the United States’ August 1978 proposal for revision of the Informal Composite Negotiating Text adopted in 1977 that the content of provision in paragraph 6 was presented for the first time in the discussions at the Third U. N. Conference on the Law of the Sea.Article 246, paragraph 6: “Notwithstanding the provisions of Paragraph 5, coastal States may not exercise their discretion to withhold consent under Subparagraph (a) of that paragraph in respect of marine scientific research projects to be undertaken in accordance with the provisions of this Part on the continental shelf, beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured, outside those specific areas which coastal States may at any time publicly designate as areas in which exploitation or detailed exploratory operations focused on those areas are occurring or will occur within a reasonable period of time. Coastal States shall give reasonable notice of the designation of such areas, as well as any modifications thereto, but shall not be obliged to give details of the operations therein.”

The U.S. did not make clear circumstances under which it submitted such a proposal, but in September 1978, it made a similar proposal[22]; in the August 1979 report of the chairman of the Third Committee, as part of its opinion about the revision of Article 246 in the Informal Composite Negotiating Text Revision No. 1, the U.S. stated that a provision of research over the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles should be included[23].“Articles 249 and 250 shall apply mutatis mutandis to marine scientific research that is of direct significance for the exploration and exploitation of the natural resources of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured.[21].”

“(b) The exercise by the coastal State of its discretion under article 246, paragraph 4 (a), shall be deferred and its consent shall be implied with respect to marine scientific research projects undertaken outside specific areas of the continental shelf beyond 200 miles, from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured, which the coastal State has publicly designated as areas in which exploitation or exploratory operations, such as exploratory drilling, are occurring or are about to occur;

(c) The coastal State shall give reasonable notice of such areas.”

After this proposal, various states actively submitted proposals at the informal meeting of the Third Committee, but the opinions of states were divided about whether coastal states could refuse to grant their consent at their discretion inside or outside those specific areas which they might designate. While states such as Brazil and Pakistan[24] proposed that coastal states could not exercise their discretion to grant consent inside “specific areas,” states such as the Philippines and Uruguay[25] proposed that coastal states could not do so outside “specific areas.” Later, they agreed on the proposed Article 246, paragraph 6 in the report of the chairman of the Third Committee in 1980 that coastal states could not exercise their discretion to grant consent outside “specific areas[26],” and this gave rise to the current Article 246, paragraph 6. The intentions of the U.S. which made the proposal in which paragraph 6 has its origin is not clear, but one of the possible reasons is that the U.S. intended to maintain a certain degree of freedom for marine research over the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles[27].

Contrary to the intentions of the U.S., however, a provision of “specific areas” in which coastal states can decide whether they should grant their consent at their discretion to research that has direct effects on the exploration and exploitation of natural resources was added to paragraph 6. In other words, this addition indicates that coastal states cannot exercise their discretion to grant consent outside such specific areas. At first glance, this seems to mean that marine research can freely be carried out in vast areas, but specific areas can freely be designated by coastal states, and moreover, there is no mention of the breadth of specific areas[28].

In this matter, there is no information that the Philippine government designated specific areas as stipulated in paragraph 6. This means that even if marine scientific research by China directly affects the exploration and exploitation of natural resources, the Philippines cannot refuse to grant its consent at its discretion.

(2) Measures taken by coastal states

As long as the Philippine government has not designated specific areas, other states can conduct marine scientific research under more relaxed regulations than over the 200-nautical-mile continental shelf. In that case, research ships are considered to be in the high seas while conducting research over the extended continental shelf. If they violate any of the coastal state’s laws and regulations, could the state take relevant enforcement measures[29]?As mentioned earlier, there is no difference between the legal nature of the 200-nauitical-mile continental shelf and that of the extended continental shelf. If so, laws and regulations that are applicable to the 200-nautical-mile continental shelf would be applied to the extended one. Even if waters over the extended continental shelf are the high seas, there would be no major problem with the application or enforcement of domestic laws and regulations if it is objectively judged that the ship concerned is conducting research on the extended continental shelf or the like[30]. In fact, there are a few states which stipulate measures to be taken for foreign ships in the high seas over the extended continental shelf in their domestic laws and enforce such laws[31]. However, since it is assumed that many of the marine scientific research projects are carried out mainly by warships or government ships because they are implemented by armed forces or government agencies, coastal states must consider immunities to be granted to such vessels or ships when they enforce laws and regulations if any of them is violated[32]. For this reason, it is expected that measures that can actually be taken by coastal states shall be extremely limited.

Conclusion

The foregoing sections discussed the legal nature of the extended continental shelf and marine scientific research conducted there. As a result, it became clear that basically, the extended continental shelf has similar legal status to that of the 200-nautical-mile continental shelf and that if marine scientific research is conducted there, regulations are applied to it in the same way as to marine scientific research over the continental shelf within 200 nautical miles even if the ship is in international waters over the extended continental shelf. But from the viewpoint of marine scientific research, it emerged that substantial restrictions may be imposed on research conducted over the extended continental shelf depending on how the coastal state establishes “specific areas” as stipulated in Article 246, paragraph 6. In any event, only a small number of states have so far established extended continental shelves on the basis of CLCS’s recommendations, and what problems marine scientific research there causes depends greatly on laws and regulations that will be enacted by coastal states in the future and enforcement measures taken thereby. Fortunately, on September 12, 2014, following the recommendations of CLCS on April 27, 2012, the Japanese government laid down the Cabinet Order on Prescribing the Areas of the Sea under Article 2, Item (ii) of the Act on the Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf for the purpose of extending Japan’s continental shelf, and on October 1 of the same year, it enforced it. The recent example of the Benham Rise is highly significant in that it aroused interest in marine scientific research as it is expected to be conducted over extended continental shelves in the future and that it attracted public attention to the necessity of legislation on the part of coastal states.This study constitutes part of the results of the Council for Science, Technology and Innovation’s Cross-ministerial Strategic Innovation Promotion Program “Next-generation technology for ocean resources exploration.”

Discussions in this article represent the author’s personal opinions and do not represent the opinions of organizations and institutions with which he is affiliated.

SHIMOYAMA Kenji

Kenji Shimoyama is an associate professor at the Japan Coast Guard Academy. Born in Hyogo Prefecture in 1977, he graduated from Kansai University Faculty of Law in 2000 and completed the requirements for doctoral course at Kansai University Graduate School of Law in 2007, but was not conferred a doctoral degree. He became a researcher at the Ship and Ocean Foundation in the same year. He worked as a junior associate professor at Kochi Junior College in 2008 and was accepted as visiting researcher at the Australian National University College of Law and at the Ship and Ocean Foundation in 2011. He became an associate professor at Kochi Junior College in 2012 and an associate professor at the Japan Coast Guard Academy in 2015, the post he has held to the present day. His publications include “Legal Status of Straits for International Navigation: The Strait of Hormuz” in “Defense Law Studies,” No. 37, 2013, “Possibilities of Regulation of Marine Structures by Coastal States(Engankoku ni yoru kaiyokochikubutsu ni taisuru kisei no kanosei nitsuite)” in “Defense Law Studies,” No. 39, 2015, and “Problems in Artificial Island Construction in Exclusive Economic Zones under International Law(Haitatekikeizaisuiikinai deno jinkotokennsetsu ni kansuru kokusaihojyo no mondaiten)” in “The Journal of Islands Studies,” Vol. 5, No. 1, 2015.

RSS

RSS