Introduction

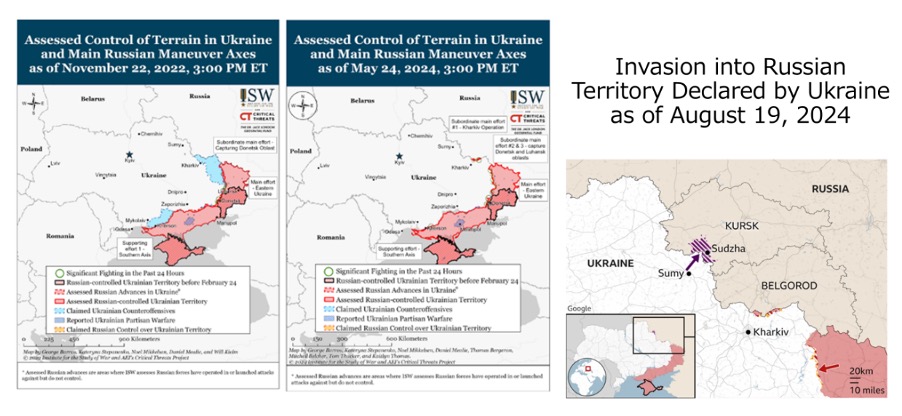

Two and a half years have passed since Russian troops invaded Ukraine. While it was initially feared that Kyiv would fall, the Ukrainian military put up a remarkable fight, quickly frustrating the Russian offensive. Russia set up its front line around Kyiv and concentrated its forces in the eastern and southern parts of the country, turning to a defensive posture. The Ukrainian counteroffensive, launched last summer with Western support, was hampered by minefields, various obstacles, and Russian positions protected by artillery, and it has not progressed as much as most spectators hoped. As the figure below shows, the fronts in southern and eastern Ukraine are largely unchanged since last summer.[1] In early August, Ukraine announced that it was conducting a cross-border offensive into Russia's Kursk Oblast. As the Ukrainian military leadership has noted, it will continue to take the initiative[2] and will likely have the effect of putting Russia on the back foot. However, due to the small size of the intrusion and its distance from the more important southern and eastern fronts, it is unlikely to make a decisive difference in the broader conflict.

Figure: State of the War in Ukraine

What a Stalemate Entails

Last November, Ukrainian General Valerii Zaluzhnyi, then commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, admitted in an interview with The Economist that the counteroffensive had lost its momentum and had turned into a “stalemate” similar to the western front of World War I.[4] He also described the situation as a “deadlock,” which has more serious connotations than “stalemate,” which has more of an impression of a draw, and said that drastic technological innovation was needed to achieve a breakthrough. He suggested there is no way for Ukraine to exit the war unless something drastic and unexpected happens.

There are no indications that the conflict will be resolved in the short term. Neither of the parties to the conflict, nor the international community, can easily find a way to drastically improve the situation, and a sense of “stalemate” is undeniable. At the same time, it is unlikely in the short term that either side will achieve a decisive victory or, conversely, that either side will be completely defeated or collapse. Although Ukraine's will to continue the fight appears firm, it will likely be extremely difficult to regain all of the territory lost to Russia – President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s stated goal – as the country is only able to maintain its resistance with Western support. On the other hand, it seems unlikely that Russia will be able to significantly expand the occupied territory enough to pressure all of Ukraine in the near future. Of course, serious concerns remain: Russian President Vladimir Putin has, since the start of the war, suggested that Russia may use tactical nuclear weapons. If Russia comes under pressure and uses nuclear weapons, even smaller ones, it will not be easy to control the escalation to an all-out nuclear exchange. If this situation – the first use of nuclear weapons in actual warfare since Hiroshima and Nagasaki – can be averted, the entire world would avoid a major catastrophe.

From this perspective, a stalemate is not necessarily the worst-case scenario. Instead, perhaps it should be seen as a realistic option to avoid the worst for the time being.

The Cost of a Stalemate: Positional Warfare and Attrition Warfare

The first image that comes to mind when one hears “stalemate” is the trench warfare of World War I. Although many of the belligerent countries had planned for a short war, the fighting turned into a four-year-long war of attrition. At the beginning of the war, both Germany and France planned to cut behind the enemy’s rear to encircle and destroy their main forces. The plan was to fight a short, decisive campaign using ambitious maneuvers, but the war resulted in mostly head-on confrontations from the very start, and for the next four years the two sides were locked in positional fighting over inches of land. The conflict turned into a massive war of attrition, with over 9 million military casualties and 10 million civilian casualties.[5]

When he admitted that Ukraine’s counteroffensive had stalled General Zaluzhnyi also noted that the country’s military had been forced into positional warfare to which it is unsuited by nature.[6] He said that Russia’s high tolerance for personnel losses, or, put differently, its high disregard for human life, puts Ukrainian forces at a disadvantage in positional warfare, where casualties tend to be high.[7] Positional warfare does indeed typically last for long periods, and casualties are high. In contrast, maneuver warfare tends to involve short, decisive battles, and the fighting is more lively and less gruesome than positional warfare. If one side’s forces are cut off before the stalemate sets in, they have no chance at survival, and they often choose to surrender, rather than be annihilated. In contrast, in positional warfare the attackers must one by one destroy pillboxes equipped with heavy weapons, fortifications that protect enemy personnel and facilities, while clearing obstacles that protect them. The defenders must defend these fortifications to the death, which is time-consuming and results in more casualties on both sides. Positional warfare that has become a stalemate carries serious costs in terms of troops losses. The economic costs are also immense. The United Nations published an estimate late last year that it would cost $486 billion to rebuild Ukraine.[8] This amounts to 11% of Japan’s gross domestic product (GDP), or nine times its total annual defense spending.[9]

For Russia too, the cost of the war is high. According to a Pentagon estimate, it has cost Russia $291 billion since the start of the war to equip, deploy, and maintain its invasion force,[10] more than one-tenth of Russia's 2023 GDP of $1.86 trillion.[11] Russian military casualties are estimated to have totaled 315,000 as of February of this year. Since the end of last year, when the war of attrition became more pronounced, the number of casualties has increased, reportedly averaging about 1,000 per day.[12] With a population of 140 million and a fertility rate of 1.4, Russia's demographics are not too different from those of Japan in terms of their size and dynamics, and its young cohort is shrinking amid a declining birthrate and aging population. Under these circumstances, it is difficult to keep over one million people mobilized. Moreover, it is difficult to believe that an operation that pays no heed to the number of casualties and disregards human life can last long.

Considering this, it would make sense for Russia to determine a stalemate is its immediate goal as a contingency plan to avoid the worst-case scenario. However, it is important to remember that a great deal of effort is needed to maintain this. The support of the international community, including the West, is essential for the Ukrainian side in particular to survive the attrition caused by positional warfare.

Stalemate in Place of a Conclusion

However, even if the aim is to maintain a stalemate for the time being, one cannot avoid thinking about where to go from there. In World War I, the Allies, led by France and the U.K., were victorious after a four-year stalemate. This came amid major changes in international relations throughout Europe, including Russia withdrawing from the front lines because of the Russian Revolution, the entry of the U.S. into the war, and the political upheaval triggered by the German Revolution. The U.S. entry into the war changed the balance dramatically, and the domestic turmoil in the belligerent countries led to a sudden loss of will to continue the war.[13]

Another place to bear in mind is the Korean peninsula since the end of the Korean War. From the start of North Korea’s southward advance in June 1950 until the spring of the following year, maneuver battles were fought across the entire peninsula, from Busan at the southernmost tip to the China-North Korea border at the northern edge. Gradually the fighting shifted into positional warfare, with the frontline stalemating around the 38th parallel. Since the armistice agreement was signed in July 1953, North and South Korea have faced each other across the demilitarized zone, but in the more than 70 years since then, fighting has not flared up in earnest.

It is too early to determine whether the stalemate in Ukraine will end because of weakening in either Ukraine or Russia, or the entry of new actors, as in World War I, or whether it will continue for decades, as on the Korean peninsula. What is important now is to recognize that efforts must be made to keep the stalemate in place for the time being, and the cost of that is no small thing.

(2024/09/30)

Notes

- 1 The war situation in Ukraine, especially on the front lines, can be found on several media and think tank websites. For example, the BBC is continuously mapping the developments of local battles on each front. However, with regard to recent macro developments, the BBC only includes position maps as of November 2022 and May 2024, suggesting there are no significant differences between them (i.e., that the counteroffensive launched by Ukraine during that period has not been very successful). The Visual Journalism Team of the BBC News, “Ukraine Tracking the war with Russia,” BBC, May 17, 2024.

- 2 Varely Zaluzhny, “On the modern design of military operations in the Russo-Ukrainian war: In the fight for the initiative,” accessed August 24, 2024.

- 3 Kateryna Stepanenko, Riley Bailey, Karolina Hird, Madison Williams, Yekaterina Klepanchuk, Nicholas Carl, and Frederick W. Kagan, “Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, November 22,” ISW, November 22, 2022; Riley Bailey, Grace Mappes, Christina Harward, Angelica Evans, and Frederick W. Kagan, “Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,” ISW, May 24, 2024; Christina Harward, Nicole Wolkov, Grace Mappes, Davit Gasparyan, Karolina Hird, and George Barros, “Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,” ISW, August 19, 2024.

- 4 “An interview with Ukraine’s commander-in-chief on the breakthrough he needs to beat Russia,” The Economist, November 4, 2023, p.45.

- 5 History.com editors, “World War I,” May 10, 2024. Updated (Original: October 29, 2009).

- 6 The concept of positional warfare and its characteristics were described in detail by Alexander Svechin, a Russian/Soviet military strategist and military thinker, in his 1926 book Strategy. Pieter Garicano, Grace Mappes, and Frederick W. Kagan, “Positional Warfare in Alexander Svechin’s Strategy,” Institute for the Studies of War, April 2024.

- 7 Varely Zaluzhny, op. cit.

- 8 Orysia Lutevych Obe, “The war rages on but Ukraine’s recovery cannot wait,” Chatham House, June 7, 2024.

- 9 IISS, The Military Balance 2024, Routledge, 2024, p. 276.

- 10 Gökhan Ergöçün, “2 years of war: Russia-Ukranie conflict exacts stinging economic costs,” Anadolu Agency, February 23, 2024.

- 11 IISS, op. cit., p.190.

- 12 Julian E. Barnes, Eric Schmitt and Marc Santora, “Russia Sends Waves of Troops to the Front in a Brutal Style of Fighting,” The New York Times, June 27, 2024.

- 13 History.com editors, op. cit.