Introduction

Due to the development of the artificial intelligence (AI) industry and the expansion of data centers in recent years, a global increase in demand for electricity is forecast, while the countries of the world are being forced to take initiatives for decarbonization for the purpose of reducing emissions of greenhouse gases. In this context, nuclear energy, together with renewable energy, has gained importance as a clean energy without emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2), which accounts for the majority of greenhouse gases. France, one of the world’s leading nuclear energy powerhouses, has been formulating an energy security strategy centered on nuclear power generation since the 1970s. France’s nuclear power industry is currently making its presence felt during the Ukraine crisis, and has come to support the energy policies of the surrounding European countries and the United States. On the other hand, political upheaval in Niger, a major source of imports of fuel uranium for electricity generation, has destabilized the supply of uranium to France.

This paper discusses the point that France’s nuclear power industry is contributing to the energy policies of the Western countries during the Ukraine crisis, and considers the future of increasingly uncertain procurement of uranium from Niger.

France’s nuclear power policies

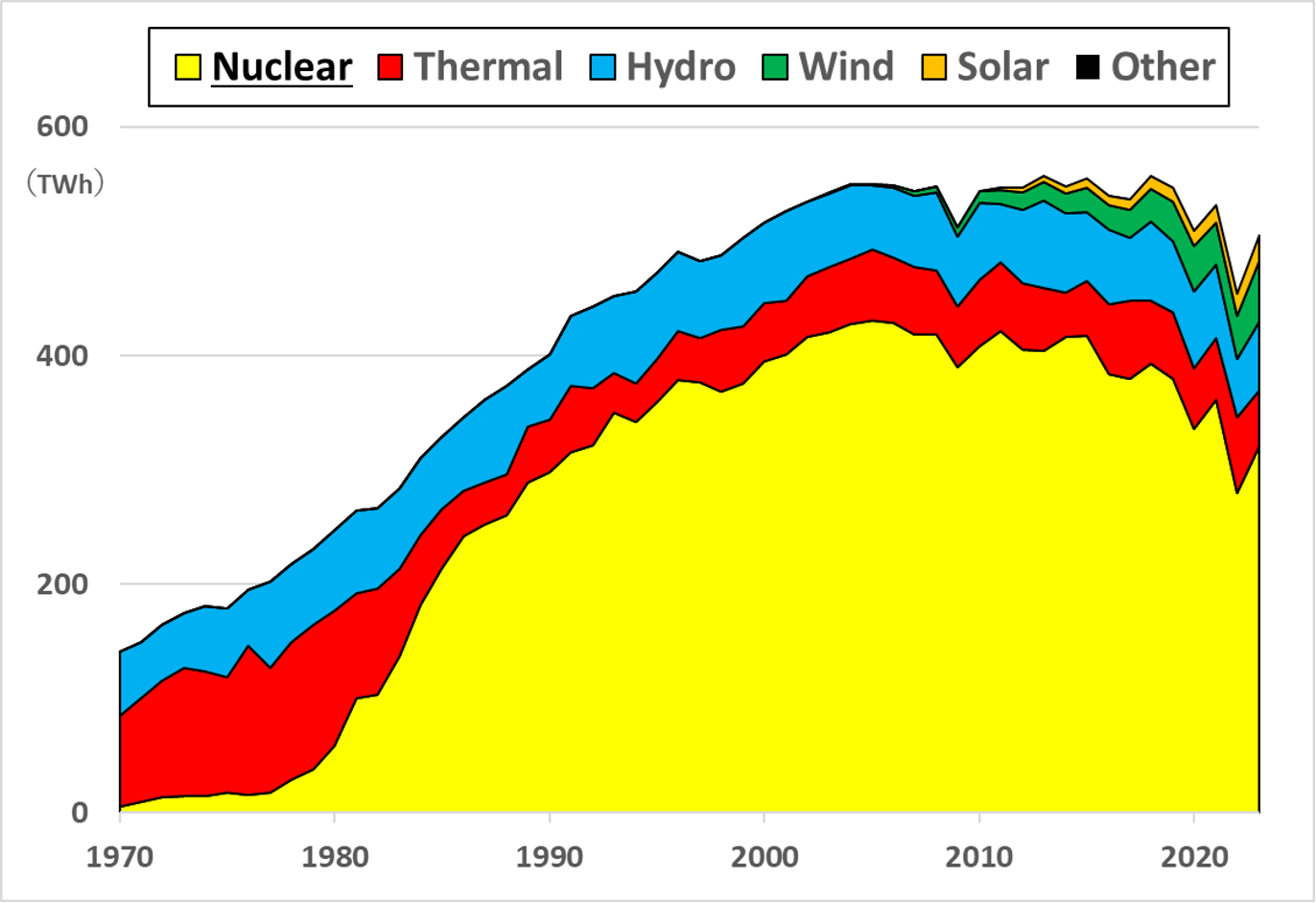

Since the end of World War II, France has pursued energy policies centered on nuclear power generation. The proportion of electricity it generated using nuclear power rose from 3% in 1970 to 70% in the mid-1980s. Since then, nuclear power generation has played the role in France of a low-cost source of electricity which can be generated stably both day and night (a baseload power source).

The background to France’s development of nuclear power technology included the military aspect of possessing nuclear weapons and the economic aspect of industrial development. Under the Fifth Republic (established in October 1958), the Charles de Gaulle administration conducted the first nuclear test in the Sahara Desert in Algeria in 1960, making France the fourth nuclear power after the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom. In the process of nuclear armament, departments were established to research plutonium production and uranium enrichment, and production and reprocessing plants were constructed. The de Gaulle administration viewed nuclear weapons not only as a tool in military strategy, but also as a means to maintain national autonomy by utilizing civilian nuclear power.[1] Moreover, since the 1960s, France has focused on developing its nuclear power industry, aiming to protect and develop an industry that is internationally competitive and technologically independent.[2]。

As of the end of 2023, France has 56 nuclear reactors in commercial operation, the second greatest number in the world after the United States (93 reactors).[3] Electricity generation derived from nuclear power has reached 320 terawatt-hours (TWh), 63% of total electricity generation (Figure 1). Like the de Gaulle administration, the current Macron administration is also working to construct independent energy policies centered on nuclear power generation. When he first took office, President Macron announced that he would reduce nuclear power dependency to 50% and decommission 14 nuclear reactors by 2035 in a form which adheres to the Energy Transition for Green Growth Act[4] enacted by the previous Hollande administration in 2015.[5] And he actually decommissioned Units 1 and 2 of the Fessenheim Nuclear Power Plant in 2020. However, in February 2022, having reaffirmed the importance of nuclear energy, the government reversed course and announced a policy of building between 6 and 14 new nuclear reactors and extending the operating life of all nuclear reactors to more than 50 years.[6]

Figure 1: Trends in the amount of electricity generated by power source in France

France supports the energy policies of Europe and the United States

France’s nuclear power industry is supporting the energy policies of the surrounding European countries and the United States from the perspectives of (i) electricity exports, (ii) construction and operation of nuclear power plants, and (iii) supply of enriched uranium. Firstly, France has built up its position as one of Europe’s leading electricity exporters through the development of its nuclear power industry. France is in a favorable geographical location for connecting to the power distribution grid and is connected to the surrounding countries (Italy, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Spain, Germany, and Belgium) by approximately 50 power transmission lines.[8] France recorded electricity exports to the surrounding countries of 77 TWh in 2023,[9] making it the largest exporter in Europe.[10]

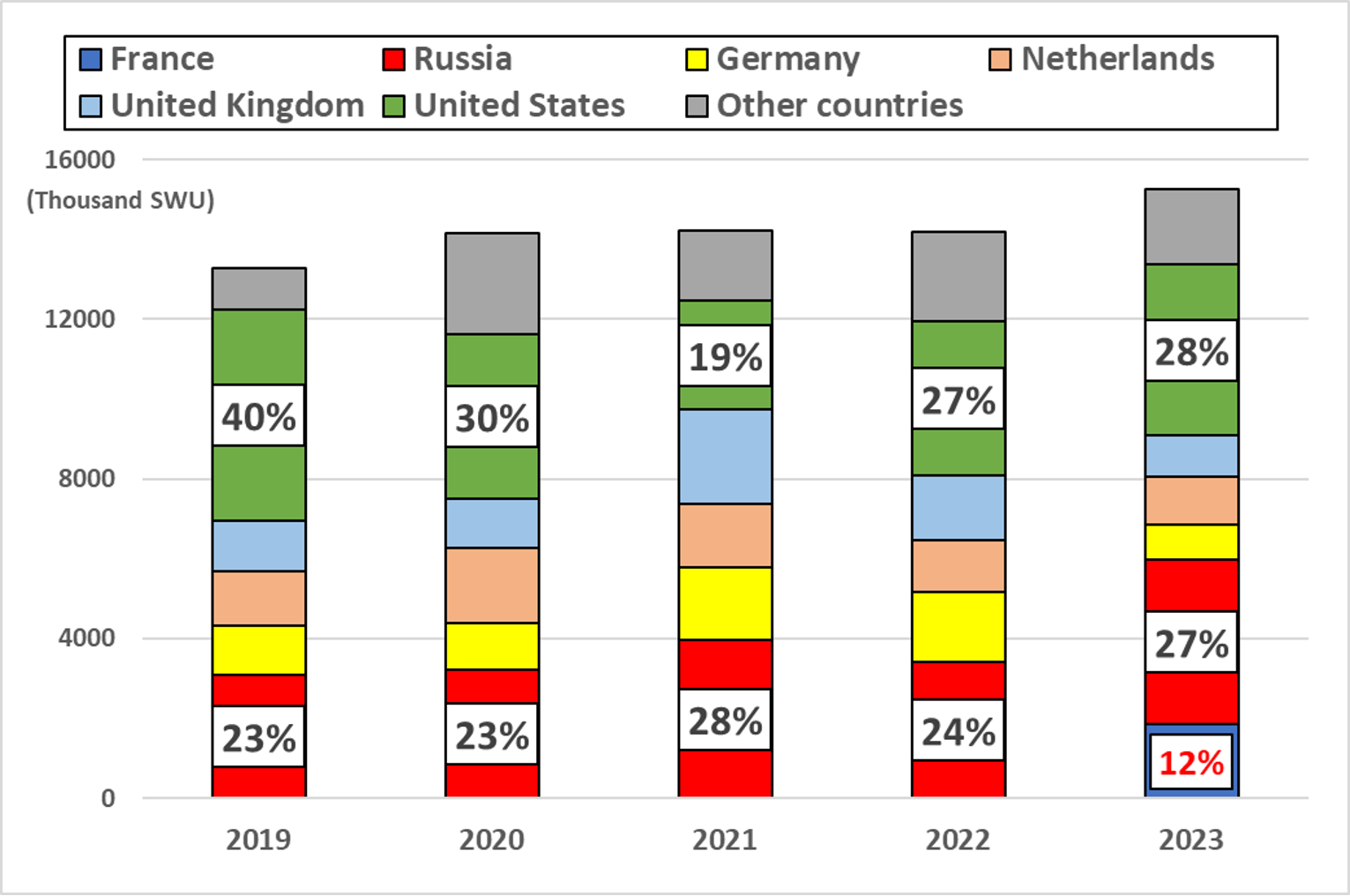

Next, French companies own and operate nuclear power plants in the United Kingdom and Belgium. In the United Kingdom, EDF Energy, a subsidiary of Électricité de France (EDF), acquired British Energy, a British nuclear power plant operator, in 2009, thereby entering the nuclear power industry of the United Kingdom. Currently, it operates a total of eight nuclear reactors at Heysham 1 Nuclear Power Station and Heysham 2 Nuclear Power Station, Torness Nuclear Power Station, Hartlepool Nuclear Power Station, and Sizewell B Nuclear Power Station.[11] Similarly, in Belgium the French company Engie manages a total of five nuclear reactors at Doel Nuclear Power Station Units 1, 2, and 4 and Tihange Nuclear Power Station Units 1 and 3 through its subsidiaries.[12] Regarding nuclear power plant construction, Olkiluoto Nuclear Power Plant’s Unit 3 in Finland was designed by French nuclear power manufacturer Framatome and constructed by French nuclear power company Areva (now named Orano after restructuring and consolidation). France also has strengths as a fuel supplier, taking advantage of its uranium enrichment technologies. Mined natural uranium is enriched and processed to be used as fuel for electricity generation, but this requires advanced technology. Orano recorded an annual enrichment capacity of 7.5 million SWUs (Separative Work Units, which represent the amount of work necessary for uranium enrichment) in 2022, which is a 12% share of the global market.[13] Enriched uranium produced in France is supplied to the nuclear power plants managed by EDF and Engie in France and other countries, and in addition in 2023 it was exported to the United States (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Purchases of enriched uranium by operators of U.S. civilian nuclear power reactors by origin country (2023)

However, it is Russia which is showing its presence in the field of uranium enrichment. The annual enrichment capacity of Russian companies reached a 44% share of the global market (27.1 million SWUs) in 2022, so Russia is dominating the Western countries in the enriched uranium market. Due to these circumstances regarding fuel procurement, Western countries have been unable to take the step of imposing sanctions on Russia’s nuclear power industry even during the Ukraine crisis.

However, the Biden administration in the United States signed the Prohibiting Russian Uranium Imports Act in May 2024, taking the step of prohibiting imports of enriched uranium from Russia.[15] In response to this, on November 15, 2024 Russia also announced restrictions on exports of enriched uranium to the United States as a retaliation.[16] In the context of the conflict between the United States and Russia over the uranium trade, France has begun to move to supply additional enriched uranium to the United States. In September, Orano announced its plan to construct a uranium enrichment facility equipped with state-of-the-art centrifuges in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.[17] Furthermore, in October, Orano’s U.S. subsidiary Orano Federal Services was selected by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) as a partner company for establishing a supply system within the United States for High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU), which is necessary as a fuel for next-generation nuclear reactors.[18]

The future of increasingly uncertain procurement of uranium from Niger

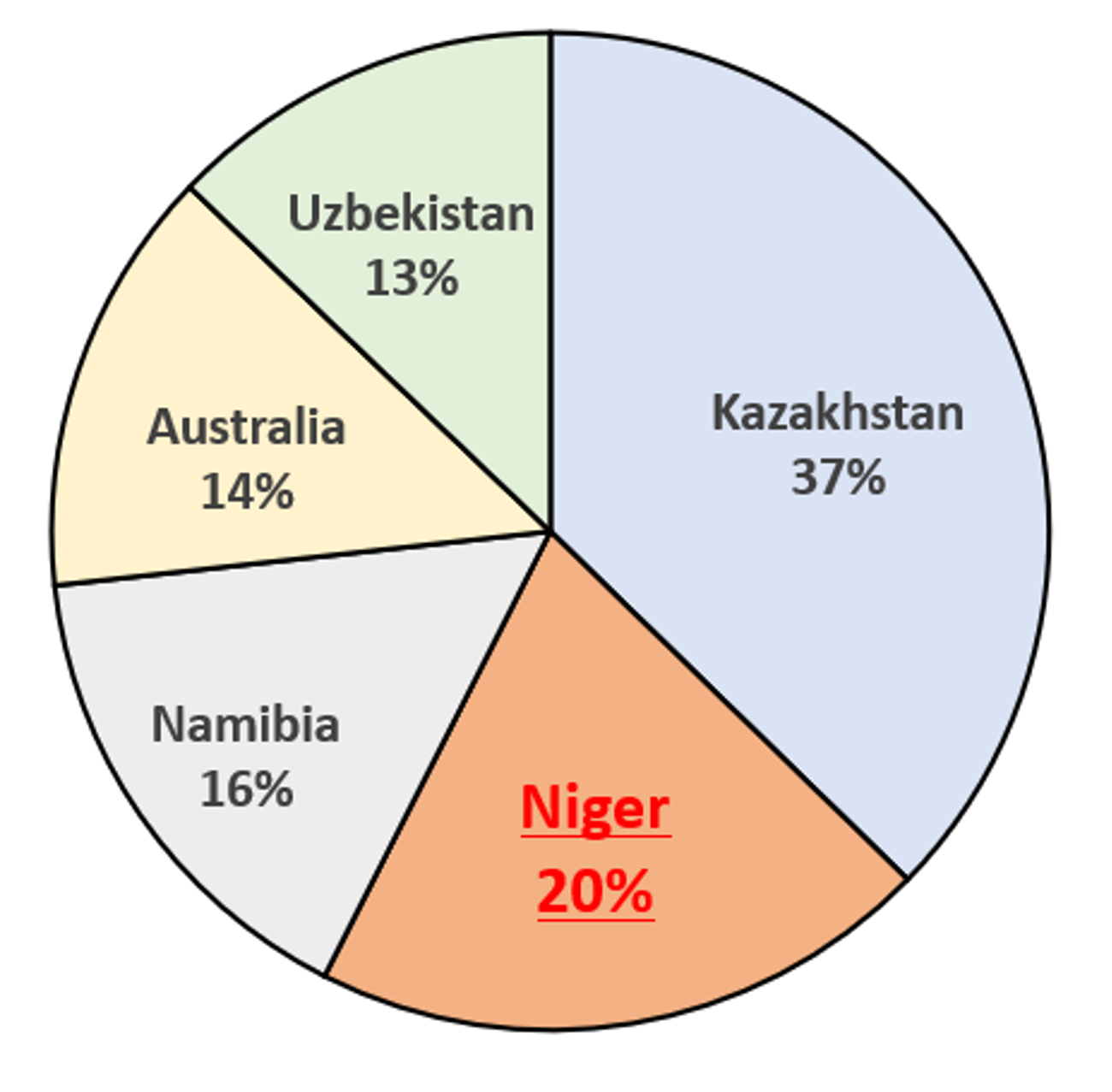

As discussed above, France is heavily involved in the operation of nuclear power plants not only at home but also in other Western countries. Due to this, it is necessary for France to continuously secure and supply uranium, the fuel, in order to ensure nuclear reactors operate stably in each country. In the past, France was able to mine uranium at home and at its peak in 1988 it recorded uranium production of 3,394 tons. However, its reserves gradually depleted and its mines closed, and as a result since the early 2000s all uranium used in French nuclear power plants has been imported, even if it has been enriched domestically.[19] Kazakhstan was the top source of uranium imports in 2022 (37% of total imports), followed by Niger (20%), Namibia (16%), Australia (14%), and Uzbekistan (13%).

Figure 3: Countries which export uranium to France (2022)

However, since 2023 France has faced obstacles in procuring uranium from Niger, where it has led resource development since the 1970s. The background to this is that an anti-French military regime took power in Niger in a military coup d’etat in July of that year. The Niger military regime took a more confrontational stance toward France and revoked Niger’s military cooperation agreements with France. At that time, France had soldiers stationed in Niger to counter Islamic militants, but in response to the suspension of military cooperation it completely withdrew its stationed troops from Niger in December 2023 and closed its embassy in Niger in January 2024.

The political upheaval in Niger also had a negative impact on Orano’s uranium production activities. Firstly, the border between Niger and Benin was closed because Benin is a member of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), which does not recognize the legitimacy of the Niger military regime. Therefore, Orano could no longer transport uranium produced in the landlocked country of Niger to the export ports in Benin. Next, in June 2024, the Niger military regime revoked the mining permit for the Imouraren mine, one of the largest in the world, which Orano had planned to develop. Then, in October, Orano was forced to suspend activities at its only production site in Niger, the Arlit mine, due to the financial deterioration of a local company owned by Orano caused by the prolonged border closure.[21] Due to this, the possibility has emerged that France will no longer be able to be involved in uranium production in Niger at all going forward.

The importance of uranium from Niger

Uranium from Niger is highly important to France because Russia is not involved in resource development there at the current time. The countries which have uranium interests in Niger are France, Spain, China, and South Korea. Meanwhile, Russia has been gaining uranium interests around the world since about 2010.[22] Furthermore, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, alternative places from which uranium can be procured, are landlocked countries, so there are some situations in which cooperation with Russia is necessary when they export their uranium; therefore, it can be concluded that Russia indirectly controls the uranium supply chain between Europe and Central Asia. Taking into account the fact that Russia has used energy supplies as a diplomatic bargaining chip, especially during the Ukraine crisis, Niger was playing an important role as a uranium supplier because France was directly involved in uranium development and could procure uranium there without going through Russia.[23]

In the last few years, Russia has taken advantage of the regional situation, which is leaning toward anti-French sentiment, to advance into Francophone African countries, with the aims of expanding its influence and acquiring economic rights. Russia is also cozying up to the Niger military regime which, after expelling the French military, went on to expel the U.S. military in September 2024.[24] Based on information from a Russian resident, Bloomberg reported in June 2024 that the Russian state-owned nuclear company Rosatom had been in contact with the Niger military regime regarding acquisition of the assets owned by Orano in Niger.[25] In August, Al-Qaeda-affiliated forces active in the Sahel region (Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger) kidnapped two geologists employed by a Russian company,[26] revealing that Russia is conducting research into Niger’s mineral resources. Given that the number of uranium-producing countries is limited, if Russia were to gain control of Niger’s uranium interests, France and other Western countries may become more dependent on Russia in the nuclear power market. In that case, there is a risk that the energy policy of decoupling from Russia, which was commenced during the Ukraine crisis with the purpose of cutting off revenues from resources that help fund Russia’s war effort, will be thwarted and then the Western countries will have no choice but to maintain their energy relationship with Russia.

(2025/01/09)

Notes

- 1 Sezin Topçu (translated by Kagumi Saito), “La France nucléaire. L’art de gouverner une technologie contestée,” édition F, 2019, p. 31.

- 2 Osamu Kumakura, “Economic Development and Public Enterprises in France: Growth and Structural Changes of Électricité de France SA (EDF),” Ashi-Shobo, 2009, p. 119.

- 3 “Nuclear Power Reactors in the World 2024 Edition,” International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), July 2024, p.8.

- 4 “Loi du 17 août 2015 relative à la transition énergétique pour la croissance verte,” Vie-publique.fr, August 18, 2015.

- 5 “Déclaration de M. Emmanuel Macron, Président de la République, sur la stratégie et la méthode pour la transition écologique, Paris le 27 novembre 2018,” Vie-publique.fr, November 27, 2018.

- 6 “Déclaration de M. Emmanuel Macron, président de la République, sur la politique de l'énergie, à Belfort le 10 février 2022,” Vie-publique.fr, February 10, 2022.

- 7 “Chiffres clés de l’énergie 2024 Edition,” Ministère de la Transition Écologique et de la Cohésion des Territoires, September 2024, p.68.

- 8 Julie Renson Mique, “Electricité: avec quels pays la France est-elle interconnectée?” L’Express, November 26, 2022.

- 9 “Chiffres clés de l’énergie 2024 Edition,” Ministère de la Transition Écologique et de la Cohésion des Territoires, September 2024, p.71.

- 10 “France tops Europe’s net power export chart,” Power Engineering International, February 6, 2024.

- 11 “Nuclear power stations in the UK,” EDF, accessed November 24, 2024.

- 12 “Nuclear energy,” Engie, accessed November 24, 2024.

- 13 “Uranium Enrichment,” World Nuclear Association, November 19, 2024.

- 14 “2023 Uranium Marketing Annual Report,” EIA: U.S. Department of Energy, June 2024, p.45.

- 15 The Prohibiting Russian Uranium Imports Act (H.R.1042) prohibited the import of Russian uranium products into the United States from August 12, 2024, while stipulating that the Department of Energy (DOE) may waive this ban until January 1, 2028, in consultation with the Departments of State and Commerce. “Prohibiting Imports of Uranium Products from the Russian Federation,” U.S. Department of State, May 14, 2024.

- 16 “Russia restricts enriched uranium exports to the United States,” Reuters, November 16, 2024.

- 17 “Project Ike Enrichment,” Orano, September 4, 2024.

- 18 “Biden-Harris Administration Announces Four Contracts to Boost Domestic HALEU Supply and Reinforce America’s Nuclear Energy Leadership as Part of Investing in America Agenda,” U.S. Department of Energy, October 17, 2024.

- 19 Pierre Breteau, “L’indépendance énergétique de la France grâce au nucléaire: un tour de passe-passe statistique,” Le Monde, February 21, 2022.

- 20 Assma Maad, “A quel point la France est-elle dépendante de l’uranium nigérien?” Le Monde, August 4, 2023.

- 21 Salimata Koné and Marie Toulemonde, “L’uranium nigérien entre dans l’ère post-Orano,” Jeune Afrique, October 25, 2024.

- 22 Masahide Takahashi, “Russia’s Nuclear Power Industry Maintains Its Global Influence: Why Is Europe Unable to Impose Sanctions?,” International Information Network Analysis (IINA), May 24, 2023.

- 23 It has been pointed out that demand for uranium from Niger is greater in the military sector than the civilian sector. While many countries impose restrictions on the military use of uranium they produce, uranium from Niger is classified as “free to use,” so France has reportedly depended on Niger in particular for the supply of military uranium. Rémi Carayol and Olivier Blamangin, “L’uranium nigérien au service de la « grandeur » de la France,” Afrique XXI, September 26, 2024.

- 24 “U.S. Withdrawal from Niger completed,” United States Africa Command, September 16, 2024.

- 25 “Russia Is Said to Seek French-Held Uranium Assets in Niger,” Bloomberg, June 3, 2024.

- 26 “Russia says it is working to free Niger hostages,” Reuters, August 10, 2024.