Introduction

Nearly two years have passed since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the Western push for energy de-Russification is yielding some outcomes. Yet, there are persistent calls for increased imports of Russian natural gas, particularly liquefied natural gas (LNG), which remains unaffected by European Union (EU) embargoes. In this context, the potential inclusion of African nations as alternative gas suppliers could bolster the Western strategy of reducing dependence on Russia. This paper examines the dilemma of expanding Russian LNG imports, a challenge to the EU’s de-Russification efforts, and underscores the significance of gas sourcing diversification from African countries.

The Challenges of the EU’s Policy of De-Russification: Expanding Imports of Russian LNG

Amidst the Ukraine crisis, the EU has pursued measures to limit the importation of Russian fossil fuels as part of sanctions against Russia, aimed at severing revenue streams that could fund the country’s military actions. Notably, coal imports were embargoed in August 2022, followed by crude oil via maritime routes in December of the same year, and petroleum products in February of the subsequent year. However, concerning natural gas, the EU has not implemented import suspensions but instead aims to reduce domestic consumption by 15% to mitigate reliance on Russian imports. According to Eurostat, the EU’s statistical office, the EU’s imports of Russian gas decreased from 154.1 billion cubic meters in 2021, pre-Ukraine invasion, to 85 billion cubic meters in 2022.

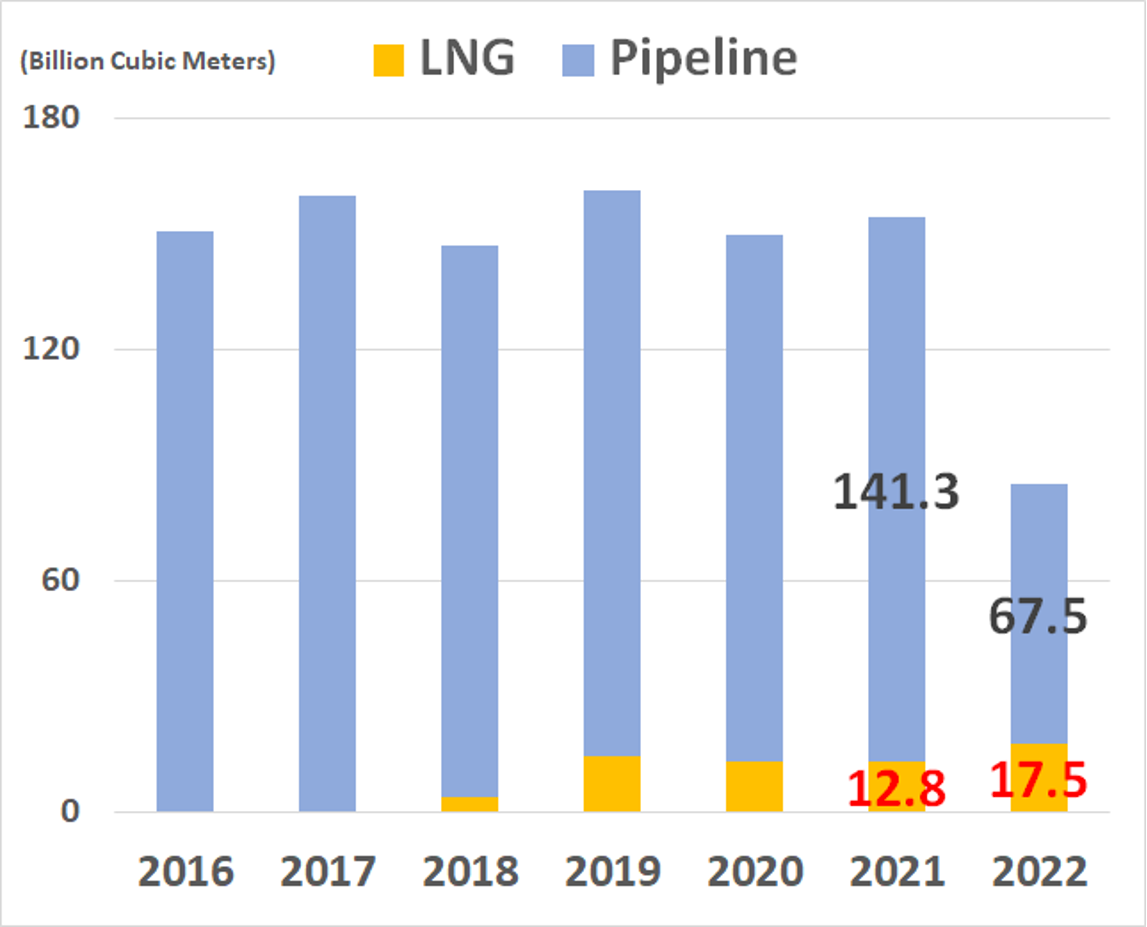

However, it’s worth noting that imports of Russian LNG are increasing. While pipeline imports have decreased by half from 141.3 billion cubic meters to 67.5 billion cubic meters, LNG imports have risen from 12.8 billion cubic meters to 17.5 billion cubic meters (see Figure 1). In terms of the distribution among member countries, France has the highest proportion of total EU imports of Russian LNG in 2022 at 29%, followed by Spain at 28%, the Netherlands at 21%, and Belgium at 15%. Most of the Russian LNG imported by each country originates from the Yamal LNG project in Sabetta, located in the northeastern region of Russia’s Yamal Peninsula.[1] This project has been a joint venture between the French company TotalEnergies, the Russian company Novatek, and other partners since before the Ukraine crisis. TotalEnergies and the Spanish company Naturgy Energy Group have each signed contracts to purchase gas from the Yamal LNG project until 2038.[2]

Figure 1: EU imports of Russian natural gas (2016-2022)

The Issue of Re-exporting Russian LNG

A notable aspect of Russian LNG entering Europe is that 21% of it is re-exported to third countries after importation. According to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), a U.S. research institute, transshipment of Russian LNG occurs at the ports of Zeebrugge in Belgium and Montoir de Bretagne in France. This gas is then re-exported to non-EU countries, including markets in Asia.

Additionally, Italy is the primary destination for re-exported LNG from Spain.[3] Spain, which has the largest LNG import capacity in Europe with seven terminals and substantial regasification facilities, actively imports Russian LNG. It then resells this LNG to third countries as Spanish LNG through transshipment or transports regasified LNG to neighboring countries via existing pipelines to generate profit.[4] Consequently, due to increased imports of Russian LNG for both domestic use and re-export by some member states, the EU’s purchases of Russian LNG nearly tripled, rising from €5.2 billion in 2021 to €16.1 billion in 2022.[5]

Although the EU has announced plans to embargo all Russian energy by 2027, current dependence on Russian LNG is increasing. In response, the Spanish government has requested its companies refrain from signing new LNG purchase contracts with Russia.[6] Additionally, the European Parliament is working on establishing rules that would enable member governments to ban Russian LNG imports by suspending reservations for Russian companies to use the infrastructure necessary for LNG exports to Europe.[7]

African Nations as Alternative Gas Sources

While it will be challenging for the EU to immediately cease Russian LNG imports, securing alternative gas sources is crucial for reducing dependency on Russia in the medium to long term. Viable candidates include the United States, which has enhanced energy cooperation during the Ukraine crisis,[8] and Qatar, which is expanding its LNG production capacity. However, in January 2024, the U.S. temporarily suspended approvals for new LNG exports to non-FTA countries due to ongoing environmental impact assessments.[9] Regarding Qatari LNG, the transportation route between Qatar and Europe via the Red Sea and the Suez Canal has faced disruptions due to maritime attacks by Yemen's Houthis. These attacks increased in frequency following the worsening conditions in Gaza in October 2023, destabilizing the Red Sea region and complicating LNG transport.[10]

Given the concerns surrounding gas procurement from the U.S. and Qatar, there are high expectations for African countries to serve as alternative gas suppliers. Geographically close to Europe and rich in gas reserves, African nations have the potential to become major natural gas exporters. According to the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF), African countries exported a total of around 86 billion cubic meters of gas in 2022, with over 60% of this amount—around 54 billion cubic meters (equivalent to 39 million tons)—exported as LNG.

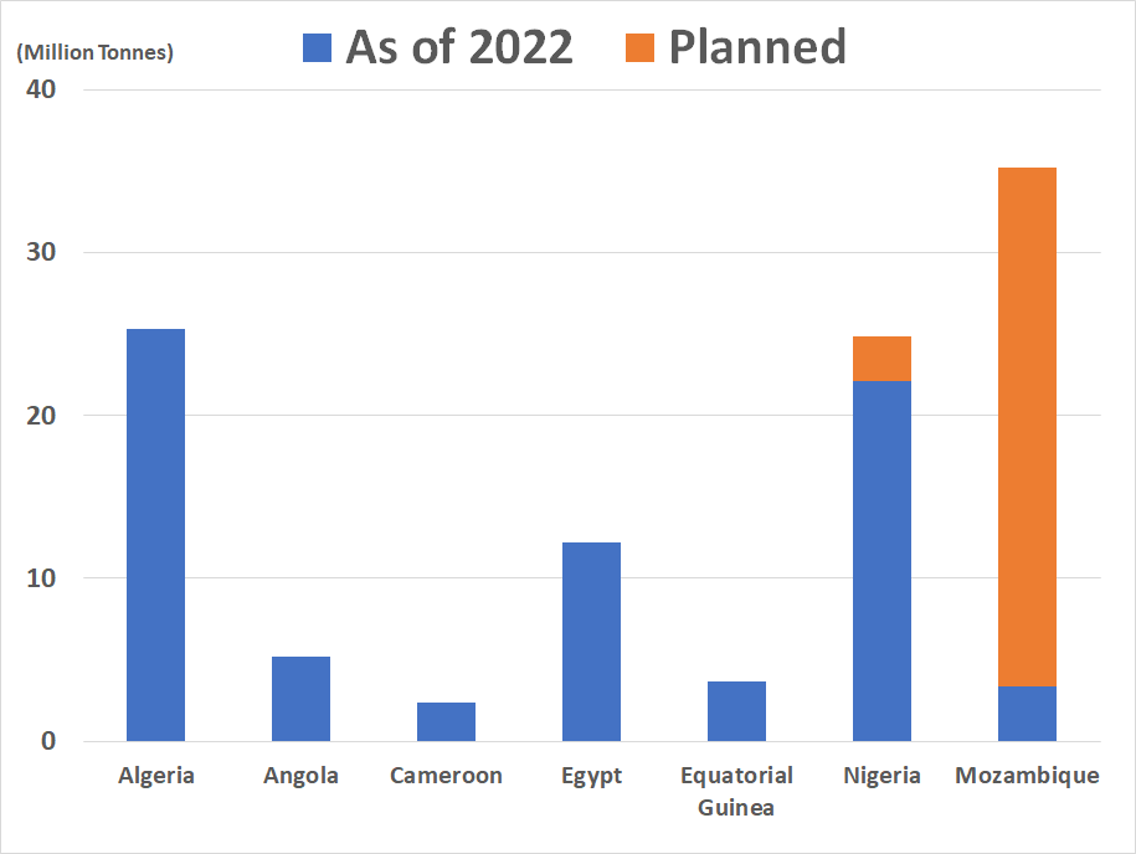

Major LNG-exporting countries in Africa include Algeria, Angola, Egypt, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Nigeria, and Mozambique. North and West African nations enjoy a geographical advantage for exporting LNG to Europe as they can bypass the Suez Canal, a significant maritime choke point, utilizing more stable shipping routes. As of 2022, these countries have a combined annual LNG production capacity of 74.3 million tons (see Figure 2). Notably, Mozambique is planning a substantial expansion of its LNG production.[11] Additionally, future production and exports are anticipated from offshore gas fields in Mauritania and Senegal, as well as southern Tanzania. By 2050, African gas exports are expected to rise to about 145 billion cubic meters through a combination of pipeline transport[12] and LNG.[13]

Figure 2: Annual LNG production capacity of African countries

Significance of African Gas for Japan

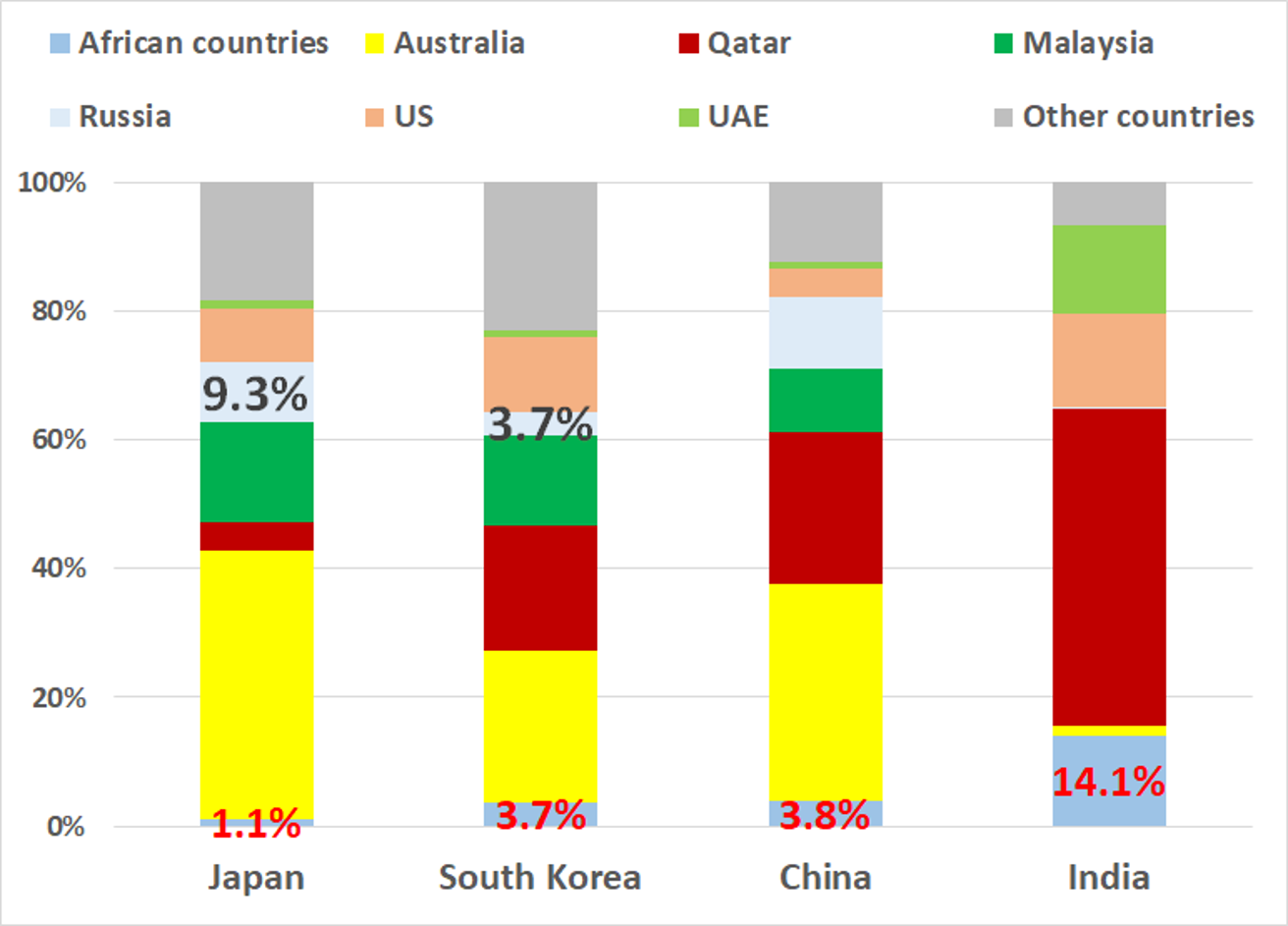

The increase in gas exports from the African region holds significant implications not only for Europe but also for Japan’s energy security. In 2023, Japan’s imports of LNG from Africa accounted for a mere 1.1% of the total, significantly lower compared to major LNG importers such as South Korea (3.7%), China (3.8%), and India (14.1%) (see Figure 3). Meanwhile, imports of Russian LNG constituted 9.3% of the total, indicating Japan’s reliance to some extent on gas supplies from Russia, which it confronts amid the Ukraine crisis, unlike South Korea, a fellow member of the Western camp. Looking ahead, as Japan further collaborates with Western nations in imposing sanctions against Russia, there is a scenario where Japan may be compelled to pursue a more comprehensive anti-Russia policy.

Figure 3: LNG import partners of Japan, South Korea, China, and India (2023)

Furthermore, there is an anticipated decline in demand for LNG for power generation as restarted nuclear power plants and the increasing availability of renewable energy sources reduce reliance on gas. However, given the volatile international energy landscape in recent years and the susceptibility of nuclear power and renewable energy to unexpected natural disasters, Japan must prioritize maintaining a certain level of gas-fired power generation to ensure a stable energy supply in the future.[15] Considering these factors, Japan should also be ready to secure alternatives to Russian LNG.

Hence, the focal point for diversifying gas import destinations lies in the development of gas fields in Mozambique, situated in southeastern Africa. Japan has contributed $14.4 billion (1.5 trillion yen) in public-private partnership financing for an LNG project in northern Mozambique,[16] where Japan holds gas interests. Furthermore, a portion of the LNG produced is slated for importation to Japan. However, an attack by Islamic extremists near the project site in March 2021 led to the project’s suspension, which has persisted since then.[17] Following this, in February 2024, TotalEnergies, the project’s operator, declared its plans to recommence LNG operations by mid-2024, citing the enhanced security conditions around the site.[18] Consequently, energy development initiatives are profoundly influenced by the security environment in resource-producing nations, highlighting the complexity of ensuring energy stability.

Nonetheless, the Mozambique LNG project holds significant importance in Japan’s strategy to diversify its sources of natural gas procurement. Positioned on the southeastern coast, away from the volatile Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden regions, Mozambique offers a route for LNG carriers bound for Japan to directly access the Indian Ocean. This strategic location enables them to circumvent the Strait of Hormuz, which carries the risk of blockade amid tensions in the Middle East. In light of these geographical advantages, Japan should collaborate with both public and private sectors to extend medium- to long-term support for the realization of Mozambique’s LNG project.

(2024/05/31)

Notes

- 1 Malte Humpert, “EU Received 300 Shipments of LNG from Russia Since Beginning of Ukraine War,” High North News, June 22, 2023.

- 2 “GIIGNL Annual Report 2023 Edition,” The International Group of Liquefied Natural Gas Importers, July 13, 2023, p.22.

- 3 Ana Maria Jaller-Makarewicz, “EU turns a blind eye to 21% of Russian LNG flowing through its terminals,” Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, November 29, 2023.

- 4 Alvaro Moreno and Vicente Nieves, “Por qué España se ha convertido en la puerta de entrada a Europa del gas licuado ruso,” El Economista, December 1, 2023.

- 5 Ana Maria Jaller-Makarewicz, “EU turns a blind eye to 21% of Russian LNG flowing through its terminals,” Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, November 29, 2023.

- 6 Pietro Lombardi, “Spain asks gas importers to wean themselves off Russian LNG,” Reuters, March 24, 2023.

- 7 Kate Abnett, “EU Parliament approves legal option to block Russian LNG imports,” Reuters, April 11, 2024.

- 8 Regarding U.S. LNG exports to Europe, refer to my paper titled “The United States as an Oil and Gas Exporting Country: Progress in U.S.-European Energy Cooperation,” International Information Network Analysis (IINA), July 24, 2023.

- 9 “DOE to Update Public Interest Analysis to Enhance National Security, Achieve Clean Energy Goals and Continue Support for Global Allies,” U.S. Department of Energy, January 26, 2024.

- 10 While Qatar’s LNG exports to Europe have not faced disruptions due to Houthi maritime attacks, alterations in LNG shipping routes—from the Red Sea to the Cape of Good Hope route—have resulted in delays in gas supplies to Italy, Spain, and the U.K. Eva Levesque, “Italy forced to wait as Qatar reroutes LNG vessels,” Arabian Gulf Business Insight, January 26, 2024.

- 11 In addition to the Mozambique LNG project, which has already received a Final Investment Decision (FID) in 2019, the Coral South FLNG (floating LNG production facility) 2 project and the Ruvuma LNG project are underway in Mozambique.

- 12 Four gas pipelines have already been laid between Europe and North Africa. There is the Medgaz Pipeline between Spain and Algeria, which connects both countries directly, and the Maghreb-Europe Gas Pipeline through Morocco. There is also the Trans-Mediterranean Pipeline between Italy and Algeria via Tunisia, and the Green Stream pipeline between Italy and Libya.

- 13 “The eighth edition of the GECF’s Global Gas Outlook 2050,” Gas Exporting Countries Forum, March 11, 2024, p.118.

- 14 The planned production increase quotas were calculated from FIDs already completed and projects scheduled for FID by 2025.

- 15 My paper, “South Korea’s Energy Policy Shift: Promoting Nuclear Power and Middle Eastern Oil Procurement...Japan, as a Competitor in Resource Acquisition, Should Watch and Take Note for the Power Sector,” Wedge ONLINE, March 27, 2024.

- 16 “¥1.5 Trillion for LNG Development in Mozambique, Japanese Public and Private Financing,” Nihon Keizai Shimbun, July 3, 2020.

- 17 The rise of Islamic extremism in Mozambique’s northern province of Cabo Delgado province could stem from ethnic tensions and the spread of conservative Islam. (“Islamic Extremism in Mozambique: Regional Expansion and Concerns about Gas Field Site Attacks,” Middle East Institute of Japan, Islamic Extremism Monitor Team, Islamic Extremism Monitor, 2020, No. 17, February 12, 2021).

- 18 “CEO: TotalEnergies hopes to resume Mozambique LNG construction by mid-2024,” LNG Prime, February 8, 2024.