In recent years, the threat posed by conspiracy theories has gained attention in the security field. This paper presents an overview of the state of conspiracy theories overseas and in Japan. From the perspective of cognitive warfare, it analyzes the reasons why they are perceived as movements that threaten our security and must be addressed through countermeasures.

Successive Attempts at Regime Destruction

The period from late 2022 to early 2023 saw a spate of attempts at regime destruction in Germany and Brazil, apparently influenced by conspiracy theories.

On December 7, 2022, the German Federal Prosecutor arrested 22 suspected members of a terrorist organization and three suspected supporters. This organization was composed of a combination of different groups, primarily members of bodies espousing conspiracy theory-based ideology, including the extreme right-wing Reichsbürger group and the Querdenker group, a movement opposing government COVID-19 policies. (Reichsbürger means “citizens of the realm,” and Querdenker literally means a “lateral thinker,” but the German term carries the connotation of a maverick who risks social outrage for unconventional thinking.)[1]

According to the investigating authorities,[2] the organization had been planning a coup d’état since November 2021, aiming to attack the German house of parliament (the Reichstag) and overturn the constitutional order of the Federal Republic of Germany. Moreover, the authorities claim that the organization planned to establish a nation resembling the former German Empire, set up a temporary government headed by its leader, Heinrich XIII Prince Reuss, and appoint a former member of parliament from the extreme right-wing Alternative für Deutschland (AfD; Alternative for Germany) party as the Minister of Justice. Soldiers and police officers were among the members of the organization, and it possessed a large weaponry. The organization believed that Germany was currently controlled by members of the so-called “deep state,” and acted according to narratives based on a confused mixture of Reichsbürger and QAnon ideology. The organization’s members believed that their liberation was ensured through the intervention of the “Allianz,” a technically sophisticated secret alliance composed of various national governments, including that of the Russian Federation, intelligence agencies, military bodies . Its members had actually established contact with counterparts in the Russian Federation.[3]

Reichsbürger was estimated to have approximately 21,000 members in Germany as of 2021,[4] and despite the arrest of the leaders of the planned coup d'état, there is a high degree of concern that similar movements will continue unabated.

An uprising also occurred in Brazil in January 2023. As in Germany, it was rooted in conspiracy theories. Around 4,000 supporters of Jair Bolsonaro, the former president of Brazil, stormed government offices in the capital, Brasília, proclaiming the illegitimacy of the results of the October 2022 presidential election, when Bolsonaro was narrowly defeated. The supporters broke into the Congress, Supreme Federal Court, and the presidential palace, starting fires and engaging in acts of vandalism and destruction. The QAnon movement had already been observed to infiltrate the groups supporting Bolsonaro,[5] and this incident in Brazil was reminiscent of the attack on the United States Capitol Building on January 6, 2021, in which adherents to QAnon’s conspiracy theories took part.[6] Former President Bolsonaro, his son Eduardo Bolsonaro, and others have established close relationships with key figures in the Alt-Right[7] movement and those associated with it, meeting with them on numerous occasions. These include Steve Bannon, formerly chief strategist and senior counselor in the Trump administration and former executive chairman of the Breitbart News Network, an online journal said to be one of the foremost Alt-Right media outlets, Jason Miller, formerly an advisor to the Trump administration and CEO of GETTR, a far-right social media platform, and Matthew Tyrmand, a member of the right-wing group Project Veritas. It has been pointed out that Bolsonaro may have learned from President Trump’s tactics in fanning conspiracy theories of election fraud.[8]

Examples have also emerged in other countries of public agitation based on theories of the fraudulent manipulation of election results. In the June 2022 Columbian presidential election, the conservative former president cast doubt on the election results. Within the Spanish-speaking world, he found a sympathetic audience in Vox, a right-wing political party in Spain, which helped to disseminate the discourse of election fraud.[9] Likewise, in the referendum to amend Chile’s constitution in September 2022, conspiracy theories concerning fraudulent voting were observed to spread on social media.[10]

Despite the geographical distance, these movements are not entirely independent of each other. It has been pointed out that all of these incidents stem from conspiracy theories of election fraud,[11] one of the forms of the QAnon narrative.[12] The fact that the political party Vox, involved in incidents in Columbia and Spain, has declared its support for QAnon conspiracy theories[13] also provides an indication of the scale of the influence of conspiracy theories based on the QAnon worldview and the power of their spread.

The Cognitive Domain as the Sixth Battlefield

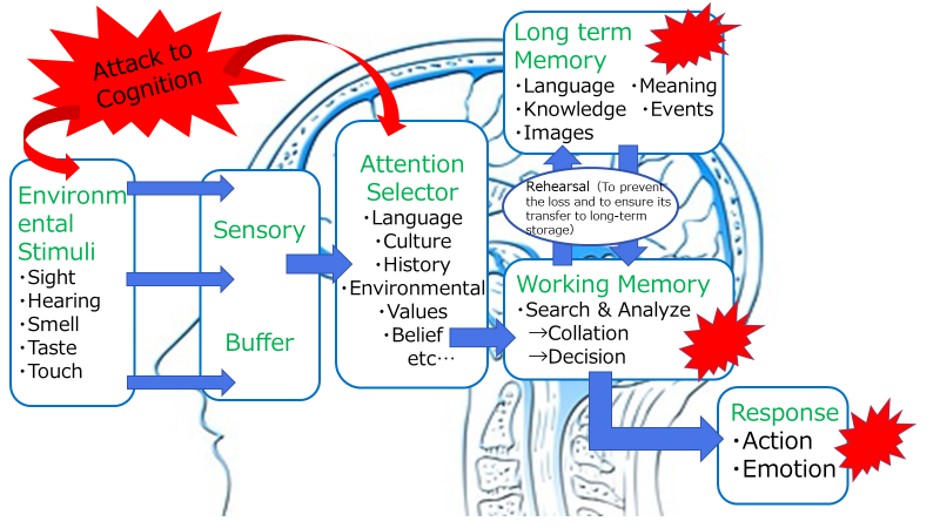

In recent years, the fight for the cognitive domain, the “sixth battleground,” has become a focus of attention. Behind this lies a shift in cyberspace information warfare and cyber warfare from attacks simply targeting information systems to cyber attacks by state actors that manipulate information to target our cyberspace-connected cognitive domain. In this context, conspiracy theories are a form of narrative that can easily influence cognition, and as such, they have become recognized as a threat. The general process of attacks on the cognitive domain of individuals is illustrated below. These attacks not only feed manipulated disinformation and false information into direct sensory inputs such as sight and hearing but also act through narratives (stories) to affect working memory based on an individual’s memories. Through cognitive filters that select and discard information, they influence the interpretation of reality (internal representation) produced within the individual’s cognitive domain. As a result, they attempt to influence the individual’s emotions and behavior and elicit the outcome which is the given objective of the attack.[14]

Source: The Sasakawa Peace Foundation Security Studies Program “Policy Proposals: ‘Prepare for Foreign Disinformation Campaigns! —The Threat Posed by Information Manipulation in the Cyberspace—” 2022, p.5

Conspiracy theories possess their own unique worldview and narrativity in the context of this process. Unlike simple, unconnected items of disinformation, they function as powerful narratives. Conspiracy theories explain the difficult realities of the world using narratives (stories) that suit the interests of their originators: some clandestine group is controlling society behind the scenes, or has developed a pathogen for world domination, or has manipulated the election, for example. The interpretations they present, once accepted, influence the working memory of the individuals who accept them, creating the cognitive filter of a conspiracy theory. These individuals will then select and discard external information through the filter of the conspiracy theory. The filter will form the basis for the processing and interpretation of a wide range of real phenomena in the cognitive domain of each individual, and they will act based on the reality they perceive through the filter of the conspiracy theory. Conspiracy theories consist of narratives that present certain interpretations of the world, and this makes them a powerful weapon in the cognitive domain.

Conspiracy Theories and Associated Cognitive Traits

What, then, is the nature of conspiracy theories? According to Joseph E. Uscinski, an authority on the study of conspiracy theories in the field of sociology,[15] “a conspiracy involves a small group of powerful individuals acting in secret toward some end, for their own benefit and against the common good.” He describes a “conspiracy theory” as “an explanation of past, present, or future events or circumstances that cites a conspiracy as the primary cause.” The QAnon idea of a shadow government — the “deep state” — that controls the world is a classic example of a conspiracy theory. Cognitive traits such as the conjunction fallacy (believing that two events (whose likelihood are both less than one) are more likely to occur together than individually), intentional bias, and a lack of analytical thinking make people more easily susceptible to conspiracy theory worldviews such as this. These cognitive traits also make cognitive warfare operations that utilize conspiracy theories highly compatible with social media environments that facilitate microtargeting,[16] making them easier to implement strategically. People who are deeply biased toward one side of a polarized debate also tend to seize on opinions that are in the interests of that side, regardless of their veracity. Conspiracy theories therefore work to utilize the structure of these existing antagonisms.[17] This is similar to the methods used to attempt to fragment society through disinformation, another reason for their compatibility. Conspiracy theories themselves are not a new form of discursive system. However, the features described above have enabled state actors to incorporate them into the disinformation operations that form part of cognitive warfare. In this way, a new rise in the cyberspace discourse of conspiracy theories has been observed in this digital age, when the advance of information technology has connected people and societies through cyberspace.

The definition of conspiracy theories and the cognitive traits associated with conspiracy theories, presented above, may give the impression that the kind of cognitive warfare that utilizes conspiracy theories is limited to the cognitive issues of individuals, confining it to low-intensity attacks that do not represent a significant threat.[18] However, it has already been pointed out that Russia and China, have “weaponized” the conspiracy theories of QAnon to engender social discord and endanger proper political processes.[19] QAnon has been indicated by the United States Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) and the FBI as a terrorism threat since 2019.[20] In terms of the intensity of the threat, it is not possible to ignore the fact that a group of adherents to QAnon conspiracy theories took part in the 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol Building, in which five people lost their lives.[21] This has led to a recognition of conspiracy theories as a new security threat.

The Spread of Conspiracy Theories in Japan

This issue is not confined to distant lands across the seas. In recent years, the influence of conspiracy theories has grown in Japan, too, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war.

QAJF (an abbreviation of Q Army Japan Flynn), a group influenced by QAnon, was active in Japan from 2019. The freezing of its members’ Twitter accounts, associated with the attack on the Capitol Building by QAnon’s base in the U.S., is considered to have led to this group losing its momentum.[22] However, this does not mean that the powerful influence of QAnon itself has waned within Japan.

Just as QAJF was losing steam, a successor was emerging. The conspiracy theory group YamatoQ, formed around October 2021, was beginning to spread. This new group pivoted on QAnon’s “deep state” conspiracy theory, while skillfully incorporating elements of anti-vax ideology and spiritualism to expand its activities. In recent years, conspiracy theory groups have integrated elements of spirituality to induce the participation of people attracted to such elements. There has also been an apparent trend to merge with existing religious groups and spirituality-based movements.[23] The concept of “conspirituality” (a portmanteau of “conspiracy” and “spirituality”) has been suggested to describe this patchwork of conspiracy theories and spirituality.[24] The exact number of YamatoQ members is unclear, but approximately 13,000 users were registered in the LINE open chat account operated by YamatoQ as of 2022,[25] and approximately 6,000 people nationwide were mobilized for a public demonstration in January the same year.[26] The point of concern here is that the group actually went as far as to demonstrate its power in the real world with actions such as attacks on vaccination centers.

Moreover, while not directly associated with QAnon, the Sanseito (Party of Do It Yourself) also demands attention as the largest organization in Japan that draws on this “conspirituality” trend. The party’s assertions and the statements made by its members demonstrate antisemitic and vaccine-related conspiracy theories, as well as elements of spirituality.[27] The Sanseito won a seat in the 2022 House of Councilors election and has 124 local legislators among its ranks. As of July 2022, it boasted approximately 94,000 members and supporters.[28] It is deeply concerning that a political party with seats in the Diet and local legislatures is spreading assertions of this nature.

Furthermore, analyses by the Internet security firm Sola.com and Professor Fujio Toriumi of the University of Tokyo[29] reveal that the clusters of social media users who posted content sympathetic to QAnon and misinformation concerning COVID-19 vaccines are also disseminating pro-Russian posts related to the invasion of Ukraine. According to these studies, the claim that Ukraine hosts a U.S.-led biological weapons research center has been reposted over 9 million times, and 228 posts claiming that the Ukraine government is run by neo-Nazis have been reposted on Twitter over 30,000 times from approximately 10,900 accounts.

There have also been cases of the reuse of Russia-linked accounts that had previously been involved in circulating disinformation during the period from the 2016 Brexit referendum in the U.K. to the U.S. presidential election. There is definitely a large number of people who, while they may not have been part of the conspiracy theory-related groups mentioned above, were nonetheless influenced by the discourses they promoted. Today, it is also vital to consider the impact on Japanese society of accounts sympathetic to the Russian narrative.

So far, Russia has had the greatest involvement in strategies utilizing the narratives of conspiracy theories. However, China is learning Russia’s methods.[30] It has even been reported that, since 2020, China has been the main proponent of QAnon’s narratives on Facebook.[31] In the context of the anticipated Taiwan contingency, it is highly likely that Japan, as part of the neighboring region, would be subject to increasingly intense cognitive warfare using methods such as this.

Under the new National Security Strategy, revised in December 2022, the terms “information warfare in the cognitive domain” and “disinformation” have been incorporated into Japan’s security strategy for the first time.[32] The task of embodying countermeasures in Japan’s legal system remains; however, it will be crucial to address the pressing issue of cognitive warfare with a sense of urgency.

(2023/09/26)

Notes

- 1 Maik Baumgärtner, Jörg Diehl, Roman Höfner, Martin Knobbe, Matthias Gebauer, Tobias Großekemper, Roman Lehberger, Ann-Katrin Müller, Sven Röbel, Fidelius Schmid und Wolf Wiedmann-Schmidt, “Die Putschfantasien der »Reichsbürger«-Truppe,” DER SPIEGEL, December 9, 2022.

- 2 Der Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, “Festnahmen von 25 mutmaßlichenMitgliedern und Unterstützern einerterroristischen Vereinigung sowieDurchsuchungsmaßnahmen in elfBundesländern bei insgesamt 52Beschuldigten,” Der Generalbundesanwalt, December 7, 2022.

- 3 Ibid.

- 4 Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat, “Verfassungsschutzbericht 2021,” Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, June 7, 2022, p.103.

- 5 Robert Muggah, “In Brazil, Qanon Has a Distinctly Bolsonaro Flavor,” Foreign Policy, February 10, 2021.

- 6 “‘QAnon Shaman’ Jake Angeli charged over pro-Trump riots,” BBC News, January 10, 2021

- 7 The Alternative Right (Alt-Right) refers to a new right-wing ideological movement that originated in the United States. Various definitions exist, but according to the Washington Post, it is defined as a predominantly online right-wing ideological movement that presents itself as an alternative to mainstream conservatism. Richard Spencer, a right-wing activist who established the Alternative Right website, is credited as the founder of both the term and the movement. Self-proclaimed Alt-Right members are mainly active on bulletin board sites such as reddit and 4chan, and the form of the movement is quite different to the highly organized activities of conventional right-wing groups.

Tierney McAfee, “What Is the Alt-Right Anyway? A User’s Guide,” People, August 25, 2016

Gregory Krieg, “Clinton is attacking the ‘Alt-Right’ – What is it?,” CNN, August 25, 2016. - 8 Nicola Abé und São Paulo, “Sturm auf den Kongress in Brasília -Wie Trumps große Lüge zum Exportschlager wurde,” SPIEGEL, January 14, 2023.

- 9 Neal Doran, “Telefónica dragged to fringes of Colombian election fraud claims,” TelcoTitans, June 21, 2022.

- 10 Leesa C. Rasp, “‘It’s not 30 pesos, it’s 30 years’: Chile’s Fight for a More Equal Society,” Australian Institute of International Affairs, November 25, 2022.

- 11 The fact that election fraud is one of QAnon’s main narratives has been pointed out in many reports. The most prominent are listed below. The Soufan Center, “QUANTIFYING THE Q CONSPIRACY: A Data-Driven Approach to Understanding the Threat Posed by Qanon”, April 2021, p.6, 18-19, 22, 36-37. Gia Kokotakis, “Into the Abyss: Qanon and the Militia Sphere in the 2020 Election,” Program on Extremism at George Washington,” Gorge Washington University Program on Extremism, March 2023, p.5.

- 12 Nicola Abé und São Paulo, “Sturm auf den Kongress in Brasília -Wie Trumps große Lüge zum Exportschlager wurde,” SPIEGEL, January 14, 2023.

- 13 “Vox demuestra públicamente su apoyo a Qanon, la teoría de conspiración que se encuentra tras el s alto al Capitolio,” ElPlural.com, January 8, 2021.

- 14 The Sasakawa Peace Foundation Security Studies Program “Policy Proposals: ‘Prepare for Foreign Disinformation Campaigns! —The Threat Posed by Information Manipulation in the Cyberspace—” —” 2022, p.4 (in Japanese).

- 15 Joseph E. Uscinski, “Conspiracy Theories: A Primer,” Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2020, pp.22-27.

- 16 Microtargeting refers to a method used to construct more effective election campaigning, marketing, and other strategies by engaging in detailed analysis of information on the individuals targeted to ascertain their preferences and behavioral patterns (Digital Daijisen, in Japanese).

- 17 Diaz Ruiz C and Nilsson T, “Disinformation and Echo Chambers: How Disinformation Circulates in Social Media Through Identity-Driven Controversies,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, July 2022.

- 18 There is still some debate regarding whether the cognitive domain should be considered a warfighting domain. The use of force is one of the criteria used to define war, and from this standpoint, discussions such as that presented in the following article question how we should determine where the threshold of war should lie, and argue that it is difficult to define the cognitive domain as a warfighting domain based on its potential to produce physical effects, which was the criterion used in the debate regarding the cyber domain. Lea Kristina Bjørgul, “Cognitive warfare and the use of force,” Stratagem, November 3, 2021.

- 19 The Soufan Center, op.cit, p.6, 25-29, 31-32.

- 20 Winter, Jana. “Exclusive: FBI Document Warns Conspiracy Theories Are a New Domestic Terrorism Threat.” Yahoo! News, August 1, 2019; “Domestic Violent Extremism Poses Heightened Threat in 2021.” Office of the Director of National Intelligence, March 17, 2021.

- 21 Jack Healy, “These Are the 5 People Who Died in the Capitol Riot,” The New York Times, January 11, 2021.

- 22 Jun Amamiya, “YamatoQ, Conspiracy Theory Groups and Conspirituality,” Shigeo Yokoyama et al., Introduction to Conspirituality — Are Spiritual People More Likely to Believe Conspiracy Theories? — Sogensha, 2023, p.93.

- 23 Proximity to religious groups has also been observed in the case of the German Reichsbürger, described above. Sonja Süß, “Ein Treffpunkt für die Verschwörungsszene,” tagesschau, February 9, 2023.

- 24 Charlotte Ward and David Voas, “The Emergence of Conspirituality,” Journal of Contemporary Religion, 26:1, 2011, pp.103-121.

The following source, provides a detailed commentary on conspirituality based on recent trend such as QAnon. Shigeo Yokoyama et al., op.cit. — However, there are those who disagree with the argument that the combination of conspiracy theories and spirituality is an exclusively recent phenomenon, citing the roots of conspiracy theories in Western esotericism.

Egil Asprem and Asbjørn Dyrendal, “Conspirituality Reconsidered: How Surprising and How New is the Confluence of Spirituality and Conspiracy Theory?,” Journal of Contemporary Religion, 30:3, 2015, pp.367-382. - 25 Gakushi Fujiwara, “Five Members of the Anti-Vax Group ‘YamatoQ’ on Trial: Spotlight on the Threat of Conspiracy Theories,” Asahi Shimbun, November 17, 2022.

- 26 “Police Monitor the Movements of Anti-Vax Group ‘YamatoQ’ amid the Spread of QAnon ‘Deep State’ Conspiracy Theories,” Yomiuri Shimbun, May 8, 2022.

- 27 Taro Arii, “The Latest on ‘Conspiracy Theories’ in Japan: The Facts about the Anti-Vax Group YamatoQ and the Sanseito,” Diamond Online, August 26, 2022; Jun Amamiya, op.cit., Shigeo Yokoyama et al., op.cit., pp.78–122.

- 28 “The Sanseito Achieves Political Party Status Two Years After Formation: Growing in Influence on a Platform of ‘Participatory’ Politics,” JIJI.COM, July 19, 2022.

- 29 Takayuki Kanamori and Kosuke Hatta, “Who Is Spreading Russian Propaganda? The Shape of Information Warfare Seen through Social Media Analysis,” Mainichi Shimbun, May 5, 2022; Fujio Toriumi, “Who Is Spreading the Idea that Members of the Ukrainian Government Are Neo-Nazis?” Yahoo News, March 7, 2022.

- 30 Joel Wuthnow, Arthur S. Ding, Phillip C. Saunders, Andrew Scobell, Andrew N.D. Yang, “THE PLA BEYOND BORDERS,” National Defense University Press, 2021, p.304.

- 31 The Soufan Center, op. cit., p.26.

- 32 National Security Council, National Security Strategy of Japan, December 16, 2022, p.24.