Japan’s Shelter Development Guidelines

On March 29, 2024, the Japanese government announced its basic policy on the construction of underground shelters in the event of an armed attack. While it identifies where such shelters are to be built to protect civilian lives,[1] the document does not explicitly state the kind of attacks the government anticipates, nor does it do enough to make up for Japan’s slow pace in establishing survival shelters.

Members of the SPF Security Studies Program’s “Study on Crisis Response in Japan” meet with experts to discuss the adequacy of the measures that have been developed in accordance with Japan’s contingency legislation. As part of this research project, the author visited Switzerland, which has enough bunker space to accommodate over 100% of its population, to inspect its fallout shelters. The visit revealed that even the most advanced countries in shelter development face challenges regarding the operation and management of emergency facilities.

In the following, I will examine the kind of shelters Japan should build through a comparative analysis of the country’s current realities with the history of bunker development in Switzerland and elsewhere.

Past and Present of Switzerland’s Fallout Shelters

The Role of Public Shelters

Switzerland quickly built fallout shelters following the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, which brought the United States and the Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war. It enacted a law in 1963 requiring all new buildings to be equipped with facilities to protect against attacks using CBRN (chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear) materials. In case providing such facilities was difficult, payment was made to secure space for family members at shelters built by the local government.[2] As a result, Switzerland today has enough emergency bunkers to house 107% of its population.[3] Shelters were also developed in many other countries around the world—notably in Europe—on the frontlines of the Cold War (Table 1).

Table 1. Percentage of the Population Covered by Nuclear Fallout Shelters

| Country | Percent |

|---|---|

| Switzerland | 107% |

| Israel | 100% |

| Norway | 98% |

| United States | 82% |

| Russia | 78% |

| Britain | 67% |

| Japan | 0.02% |

Source: Created by the author based on materials published by the Japan Nuclear Shelter Association.

The Sonnenberg bunker, which the author visited, is located in Lucerne, a city of 80,000 in central Switzerland. Construction began in 1970 by utilizing the underground space created by a tunnel built along the A2 Motorway. When completed in 1976, it was capable of housing 20,000 people, or a quarter of the city’s population.[4] The entire bunker is shielded from radioactive fallout by a concrete wall over 30 centimeters thick. It was equipped with an emergency hospital with operating rooms, a command post to maintain security inside the shelter, water storage tanks, a generator, food storage and cooking facilities, and ventilation machines. It was designed to accommodate 20,000 people for two weeks.

Shelters in Switzerland are operated and managed based on the concept of civil defense, with civilians being mobilized and organized to perform various protection duties. National defense is considered a duty of Swiss citizens, and as my Sonnenberg tour guide explained to me, copies of government-issued booklets on civil protection are distributed to all households, which stipulate the roles civilians are to play in support of military and medical personnel in case of a nuclear attack. Until the 1990s, she said, emergency drills were regularly at the bunkers.[5]

Shelters in Switzerland Today

Switzerland’s view of emergency shelters underwent a change, however, following the end of the Cold War. As fears of nuclear war abated, people began questioning the cost of maintaining public bunkers like Sonnenberg—which ran to an equivalent of tens of million yen each year. They also recognized the limitations of such facilities. “Nuclear shelters may protect you against blinding light, intense heat, bomb blasts, and radioactive dust,” my guide told me, “but they can’t keep the public safe from residual radiation that remains long after a nuclear explosion.”

In 2006, Sonnenberg was scaled down to one-tenth its former size, with much of it, along with other public bunkers, being sold to private companies. It also served as temporary housing for some of the hundreds of thousands of refugees who reached Europe from Africa and the Middle East in 2015. “The drills that used to take place regularly aren’t held anymore,” my guide said. But following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Swiss government has once again been emphasizing the importance of public shelters, announcing a “Shelters for the Population” policy and prohibiting additional sales to the private sector.[6]

The Situation in Japan

The Japanese government’s recently announced basic policy gives priority to the construction of underground shelters in the Sakishima Islands near Taiwan in anticipation of a contingency there. Because the islands are geographically remote, making evacuation difficult without planes or boats, the policy calls for establishing emergency shelters in five Sakishima municipalities, including the cities of Ishigaki and Miyakojima.

The technical guidelines specify that the facilities should be constructed as deep underground as possible and covered with steel-reinforced concrete walls more than 30 centimeters thick to withstand missile blasts. The shelters should provide 2 square meters of space per evacuee and have facilities for food storage, electric power, communication, and ventilation so people can survive for approximately two weeks. The only government measures until now had been the stipulation of “evacuation facilities,” “emergency temporary evacuation facilities,” and “underground facilities” under Article 150[7] of the 2004 Act concerning the Measures for Protection of the People in Armed Attack Situations, etc. (Civil Protection Act), but there had been no mention of how long evacuees were to stay in such facilities.

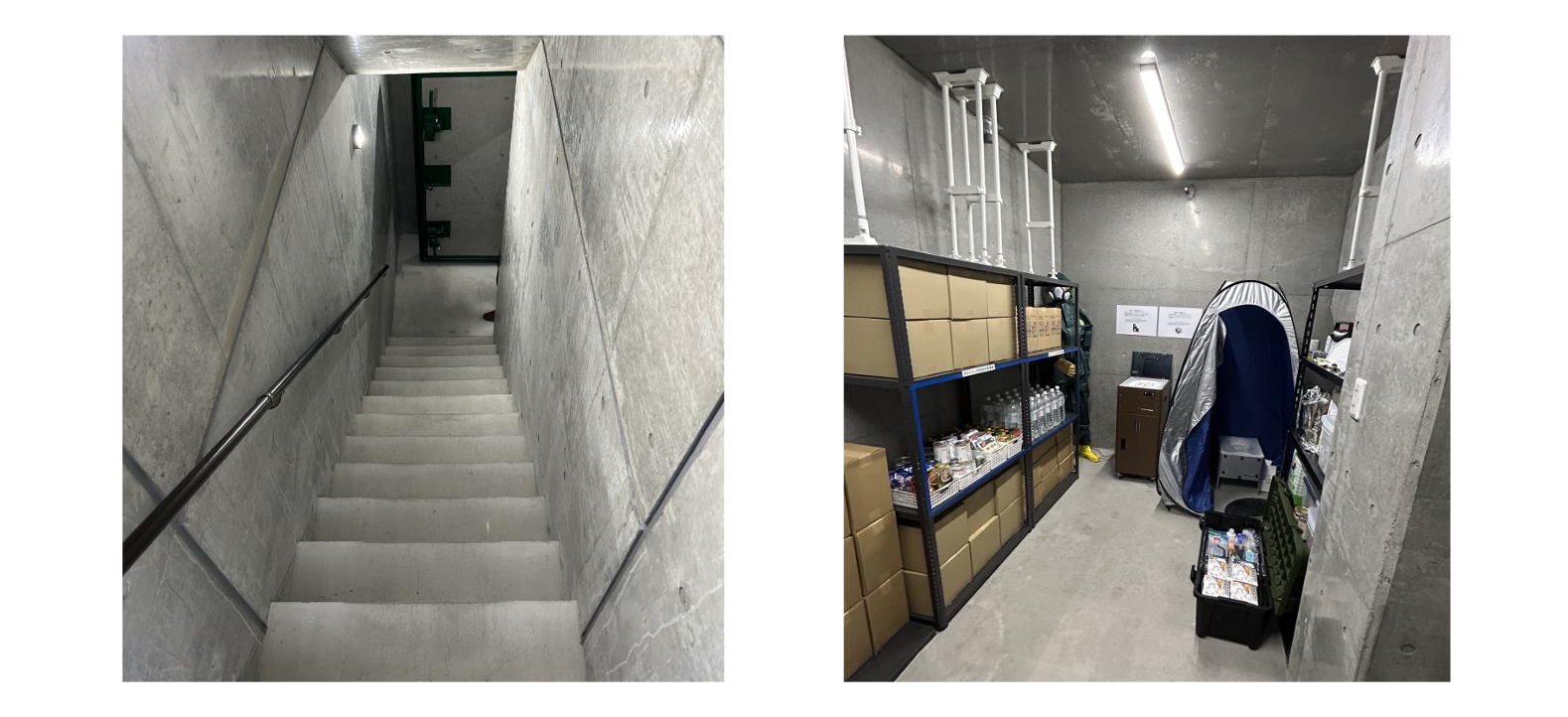

There are 97,974 places nationwide that have been designated “evacuation facilities,” but most are simply open spaces, like playgrounds, that have no protective walls. The 56,173 “emergency temporary evacuation facilities,” meanwhile, are concrete facilities designed to mitigate damage from ballistic missile blasts, but the majority are government buildings and schools. On the other hand, there are only 3,336 “underground facilities,”[8] with few being located in urban areas with large populations. Bunkers capable of withstanding a nuclear attack are largely privately owned and cover a mere 0.02% of the population (Table 1). This had prompted the Tokyo metropolitan government to develop a plan—before the recent announcement of the basic national policy—to convert underground emergency warehouses for its subway system into fallout shelters.[9]

Unlike the Swiss concept of civil defense, the responsibilities for guiding people to these facilities, as well as for their operation and management are not legally mandated. The Japanese Constitution makes no mention of people’s duties regarding the defense of the homeland, while the abovementioned Civil Protection Act only stipulates that responses to emergency situations be based on the voluntary cooperation of the people.[10]

Two Issues to Address

The growing challenges in Japan’s security environment suggest a heightened need to develop emergency shelters. This will require addressing two major issues in the light of Japan’s current realities and the history of bunker development in countries like Switzerland.

The first is establishing clearer guidelines on the kind of facilities to build and what functions they are to serve. The government’s basic policy outlines the construction of emergency evacuation shelters that are able to withstand bombs, artillery shells, and conventional warhead blasts during four types of armed attack: amphibious invasions, attacks by guerrilla or special forces, ballistic missile attacks, and aerial strikes.[11] It is not clear, however, whether they are meant to resist attacks from conventional weapons only or also from those using CBRN materials. This distinction is important because it will affect the required robustness of the shelters and the scale of ventilation. If the emergency evacuation shelters and the urban underground bunkers expected to be built henceforth do not assume nuclear, biological, and chemical attacks, then additional measures will be needed, such as plans for massive evacuations from the site of the attack and the designation of medical facilities to treat seriously injured people. If shelters are to be built merely to boost the coverage rate, they are unlikely to provide adequate protection in an emergency.

The second issue that must be addressed is ensuring and maintaining the effectiveness of evacuation measures. One approach is to reinforce the exercises conducted in anticipation of an armed attack. Such exercises were held by 17 prefectures during fiscal 2023, but they were mostly simulations; only 2 prefectures conducted actual drills.[12] There is room for debate on whether such exercises should be made the duty of citizens, as is the case under the Swiss concept of civil defense, or be based on the voluntary cooperation of the public. But in either case, regular drills will allow the national government, local municipalities, and residents to gain familiarity with procedures for guiding people to and operating evacuation shelters. As the Swiss experience suggests, conducting drills when international tensions are easing can be difficult, so now is probably the best time to enhance preparedness by conducting more drills.

Addressing these two issues will not only lead to enhanced protection for the people. The demonstration of a strong public will to overcome armed aggression could force a potential aggressor to abandon its invasion plans and thereby help strengthen deterrence.[13] The announcement of the government’s basic policy should be seen as an opportunity to raise the public’s interest in shelter development and in dealing with an armed attack.

(2024/05/29)

Notes

- 1 Cabinet Secretariat, Civil Protection Portal Site, “Buryoku kogeki o sotei shita hinanshisetsu (sheruta) no kakuho ni kakawaru kihonteki kangaekata” (Basic Policy on Securing Evacuation Facilities [Shelters] in the Event of an Armed Attack), March 29, 2024.

- 2 As explained to me by a tour guide for the Sonnenberg bunker in Lucerne.

- 3 Ibid.

- 4 “Surviving Underground: Guided Tours of the Sonnenberg Civilian Bunker” (brochure in English).

- 5 The Japanese edition of “Civil Defense,” edited by the Swiss government, May 2022, Hara Shobo. Details on how to respond in the event of a nuclear attack are introduced on pp. 72–91.

- 6 Swiss Federal Office for Civil Protection, “Shelters for the Population,” November 22, 2023.

- 7 Article 150 of the Civil Protection Act states that the government shall conduct surveys and research on evacuation facilities with the functions necessary to protect people’s lives and bodies from armed attack and shall endeavor to promote the development of such facilities.

- 8 Cabinet Secretariat, Civil Protection Portal Site, “Hinan shisetsusu ichiran” (List of Evacuation Facilities in Japan), accessed April 9, 2024.

- 9 Press conference by Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike, January 26, 2024.

- 10 Article 4 of the Civil Protection Act states that citizens shall endeavor to cooperate as necessary when requested to do so in implementing civil protection measures pursuant to the law’s provisions. Such cooperation shall be left to the voluntary will of the citizens, and no coercion shall be used in making such requests.

- 11 Cabinet Secretariat, Civil Protection Portal Site, “Tokutei rinji hinan shisetsu no gijutu gaidorain (gaiyo)” (Technical Guidelines for Emergency Evacuation Shelters [Summary]), March 2024.

- 12 Cabinet Secretariat, Civil Protection Portal Site, “Kokumin hogo kunren” (Civil Protection Drill), accessed April 8, 2024.

- 13 Koji Kusakabe, “Nihon-gata minkan boei wa kano ka” (Is Japanese-Style Civil Defense Possible?), Matsushita Institute of Government and Management, October 29, 2005.