Publication of working papers for the SPF project “Shaping the Pragmatic and Effective Strategy Toward China”

IINA (International Information Network Analysis) will upload the working papers written by U.S. and Japanese project members focusing on shaping a pragmatic and effective strategy toward China. We hope that this series will help IINA readers understand how experts from the U.S. and Japan see China and the U.S.-Japan joint efforts, which have the potential to determine the future world order.

In August 2021, Chinese President Xi Jinping made the following critical remarks on the issue of "common prosperity":[1]

“Common prosperity is the prosperity of all the people, not the prosperity of a few people, nor is it tidy egalitarianism;”

“We allow some people to get rich first, and let those who get rich first help others get rich later”

“We should build a basic institutional arrangement that coordinates the primary, secondary, and tertiary distributions. We should also strengthen taxation, social security, and transfer payments and improve the precision thereof, expand the proportion of middle-income groups, and increase low-income groups' income;”

“We should reasonably adjust excessive income, clean up and regulate unreasonable income and resolutely outlaw illegal income. We should also encourage high-income people and enterprises to give back more to society.”

President Xi has mentioned "common prosperity" several times, but these remarks were the first indication of a specific policy. The unveiling comes as he and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) grow increasingly concerned about the widening gap between the rich and the poor.

Ordinary People’s Fading “Chinese Dream”

Dissatisfaction with the widening wealth gap in China is growing among the general public, especially young people, as indicated by the recent emergence of two buzzwords on the Chinese internet. One is “lying flat-ism (躺平主义),” a mentality adopted by young people that rejects the exhausting daily work grind. Even if one works hard, they cannot afford a house or marry an ideal partner, so it is better to become a “couch potato.”

The other phrase is “996,” which means “work from 9 am to 9 pm, 6 days a week.” 996 has actually long been a popular employment practice at private Chinese companies, but it has now become a target of young people’s resentment. In the past, their hard work would earn them a house and future pay increases, but few now hold on to such expectations.

In short, the "Chinese dream" seems to be fading for ordinary people. The CCP's legitimacy has been underpinned by the people’s sense that their lives are getting better year by year. If this sentiment is diminishing, it will seriously impact the CCP's rule. President Xi expressed this grave concern in January 2021, saying, "Achieving common prosperity is not only an economic issue but also a major political issue related to the Party's ruling base. We must never allow the gap between the rich and the poor to grow wider[2]."

Crackdown on Chinese Platform Companies

Signs of policy change began to appear late last year. In November 2020, Ant Group Inc., Alibaba's fintech company that was about to list in the stock exchanges of Shanghai and Hong Kong, was forced by financial authorities to drastically change its business model and abandon its listing. The news sent a major shockwave through the financial market, as the company planned to raise $34.5 billion and had already gathered $3 trillion in subscriptions.

Initially, this punishment was considered an individual case for founder Jack Ma and his company for not following the guidance of the financial authorities and provocatively criticizing the government. But after that, the guidance on cleaning up financial businesses and investigations of antitrust violations spread not only to Alibaba's headquarters, but also to Tencent, Meituan (美团:a food delivery service), and DiDi (滴滴:a ride-share service). It became clear that this was a crackdown on the entire Chinese platform industry.

DiDi was listed on the New York Stock Exchange at the end of June 2021. But a few days later, it was severely punished by China's information security authorities and saw its stock price plummet by half and its market capitalization cut by $40 billion.

There are several reasons why the Chinese government has successively levied such harsh punishments on platform companies. One is that they are causing serious problems for financial regulation and antitrust policy. Additionally, the Communist Party is very wary that platform companies are becoming "the fourth estate in the 21st century" with enormous influence over the public.

At the same time, these companies and their founders struck the nerves of Xi and the CCP. These privately-owned platforms go public overseas, boast market capitalizations that surpass those of China's largest state-owned enterprises, and make their founders fabulously wealthy. In the eyes of Xi and the CCP, something like this should not happen in China.

Having seen these harsh punishments and heard Xi's call for the rich to give back to society, the founders and CEOs of platform companies have rushed to donate money to public welfare projects[3].

Xi is not the only world leader who believes that the widening gap between the rich and the poor must be rectified. The tide of global economic policy in the 21st century seems to be turning from neo-liberalism to a focus on the equitable distribution of wealth. Such is also the case in China, although there are many differences in details. And Xi's policy is being implemented faster than other national leaders’, including U.S. President Joe Biden's plan to raise taxes on the wealthy.

Core Reasons behind China’s Wealth Disparity

But cracking down on platform companies and forcing their founders to donate huge sums of money will do little to narrow the gap between the rich and the poor in China. The problem of wealth inequality in China today is not so much a problem of income distribution as it is the asset gap between "the haves and the have-nots." There are two primary reasons for the growing asset gap.

(1) Real Estate Bubble

One is China’s real estate bubble. For many years, the Chinese government has allowed real estate prices to soar to unreasonable levels, as real estate investment helps boost the economic growth rate and generate revenue for local governments.

As a result, real estate prices in China are absurdly high. A famous Chinese real estate executive claimed in 2018 that the total market capitalization of Chinese real estate had exceeded that of Japan, the United States, and Europe combined, and had reached $65 trillion[4].

From the demand side, unreasonably high real estate prices are evident in the ratio of “real estate prices/average annual income of workers.” This ratio is considered normal if it is around five. In 2020, however, China’s 50 major cities averaged a ratio of 13.4. The ratios in the cities of Shenzhen, Shanghai, and Beijing were absurdly high at 39.8, 26.2, and 23.8, respectively[5].

From the supply side, the rent/property price (i.e., investment yield) warrants attention. In 2020, this ratio was 2.1% in Shanghai, 1.7% in Beijing, 1.5% in Guangzhou, 1.3% in Shenzhen, and 1.7% on average in the ten largest cities. Considering the fact that the bank loan's prime interest rate is 4.5%, property prices are unrealistically high[6].

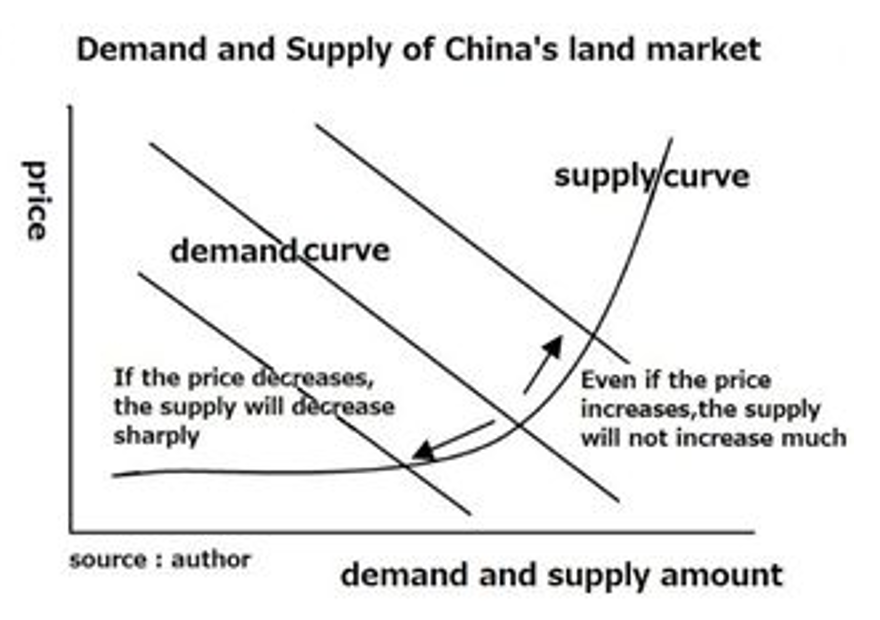

China's urban land market is a supply monopoly market where the only seller is the local government, which auction off land. That makes it difficult for a sudden rush to sell to occur, which would in turn burst any real estate bubble. Even if the market were to call for an adjustment of excessively high prices, a decrease in transactions would result, rather than a fall in prices (see the right chart).

Because of this market structure, it is unlikely that China's real estate bubble will burst any time soon. Still, it is precisely for this reason that wealth is concentrated in real estate owned only by a few (the local government and wealthy people). The structure is fixed such that real estate owners collect wealth in rents from those who do not own. Thus, the wealth distribution in China is being distorted cumulatively by a huge magnitude. One can describe the distortion as an "economically unjustifiable wealth transfer.”

(2) “Implicit Government Guarantee” for Financial Debt

The other major reason for the widening asset gap is that China has continuously postponed the disposal of zombie companies with bad debts that cannot be repaid. This inaction has dramatically distorted China's distribution of wealth.

Thanks to the 'implicit government guarantee,' zombie companies can refinance their bad debts. As a result, they continue to pay interest to creditors who should have faced losses on their bad loans; in other words, they are not entitled to receive interest. The scale of such payments can also be described as an “economically unjustifiable wealth transfer.”

China's outstanding financial assets are roughly RMB 300 trillion. If we use the “interest expense > EBITDA” rule of thumb, 15-20% are latent, non-performing assets that should be written off as losses because the debtor companies cannot repay them alone (see Column).

Assuming that financial assets worth RMB 45 to 60 trillion (15-20% of 300 trillion RMB) receive an average annual return of 5%[7], that would mean that RMB 2.25 to 3 trillion per year is paid to creditors or shareholders who are not entitled to receive this money. Since China's GDP is now around RMB 100 trillion (around $15 trillion), the scale of wealth transfer is equivalent to 2-3% of GDP ($300-$450 billion) every year. For reference, the aggregated amount of payment by China’s public pension mechanism was around RMB 5 trillion in 2019[8]. This offers a measure of comparison for the magnitude of this wealth transfer.

In an ordinary country, the scale of this kind of unjustifiable wealth transfer is limited because interest rates would fall sharply after the investment bubble bursts. However, in China, where the government (sovereign) bond yield is over 3%, the size of wealth transfer through this mechanism is massive and is seriously undermining the country’s economic health.

It is a wealth transfer to the state-owned economy, which controls the financial sector and the wealthy people who deposit money there.

[Column: the Size of China's Bad Loans]

The latest bank Non-Performing Loan (NPL) ratio published by the CBIRC (China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission) is 2.0% (Sept. 2020), but the actual ratio is thought to be much higher. The most detailed analysis on this topic is the IMF's Global Financial Stability Report (Apr. 2016[9]. This survey notes, “A company is defined as ‘at-risk’ if it generates insufficient EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) to cover its reported interest expense” (i.e., interest coverage ratio (ICR) < 1). As a result, 15.1% of Chinese corporate loans made by commercial banks were judged to be “at risk.”

The survey further noted:

- There is another view that the “loan at risk” threshold of “ICR<1” is too low and should be ICR<2 or at least ICR<1.5. In this case, the ratio of corporate loans classified as “at-risk” (≈NPL ratio) rises to 27% and 22%, respectively, and more importantly,

- Loans by state-owned policy banks (such as the National Development Bank that primarily loans to local governments) and commercial bank loans for local government financial vehicles (LGFV) guaranteed by the local government are excluded from this survey.

While the author agrees that there is little need to worry about severe defaults on loans to LGFV, it is still problematic that continuing interest payments on non-performing loans cause an unjustifiable wealth transfer.

According to the most recently available data, as of the end of 2018, the outstanding debts of LGFV have surpassed RMB 30 trillion (roughly 33% of GDP), while their ICR is only 0.4 on average[10]. When this is considered together with the non-performing loan ratio surveyed by the IMF, the size of bad loans that cause unjustifiable wealth transfers may be even higher than 20%.

A Truly Necessary Prescription

This paper argues that the primary reason for the widening gap between the rich and the poor in China is the "unjustifiable wealth transfer" brought about by the huge scale of real estate bubble and implicit government guarantee for financial debts. Based on this hypothesis, what should Xi and his party do?

If real estate prices were to fall sharply, most banks using real estate as collateral for loans would face insolvency, and the entire economy would take a major hit. This was the lesson of Japan’s experience after its own bubble burst in the 1990s.

If the practice of implicit government guarantees abruptly stops, lenders may rapidly withdraw their funds for fear of being burned, which would cause a large-scale credit crunch.

In short, there is no immediate and straightforward prescription to rectify the root causes of the widening asset gap. Therefore, Xi and the party should focus on "secondary distribution," that is, as he said in August 2021, “strengthening and improving the precision of taxation.”

Specifically, a property tax on real estate and an inheritance tax on real estate or financial assets need to be introduced. Officials recently decided to implement the property tax on a trial basis, but due to persistent reluctance within the CCP, the number of target cities has been reduced from the originally planned 30 to 10, according to a news report[11]. Regarding the latter, neither the CCP nor the government has signaled such a plan is in the works.

If such tax measures are introduced, then they will hit the economic interests of the government, the CCP and their related privileged individuals substantially. As such, they will likely face significant resistance.

Further Impediments Ahead

In November 2018, President Xi Jinping made an unfamiliar statement about the “56789 characteristics of the private economy[12].” He said, "Private enterprises contribute; more than 50% of the tax revenue; more than 60% of the GDP; more than 70% of the innovation results; more than 80% of the employment, and more than 90% of the enterprises are private enterprises.” It seems that President Xi wanted to encourage private entrepreneurs who had become increasingly pessimistic about the future.

It is fine to praise and encourage private enterprises, but there is room for the opposite view to this statement. In economics, there are the concepts of"flow," as in an income statement, and "stock," as in the table of assets and liabilities. The tax revenue and GDP cited by Xi are flow. When hearing that the private enterprises play a leading role in flow, one naturally wonders, "So who is the leading player in stock?

China is said to be a country with a “socialist public ownership system (formal name: 全民所有制: socialist ownership system by all the people),” but in reality, wealth is overwhelmingly concentrated in the government, the CCP that controls the government and privileged individuals called “red aristocracy” or “princelings.”

The local government owns the land of an urban area, and the wealth generated through the auction of that land goes to the government.

The most profitable land often goes to the government-affiliated developer, a company connected through privileged individuals, or other big developers who can pay large sums to the local government at the auction.

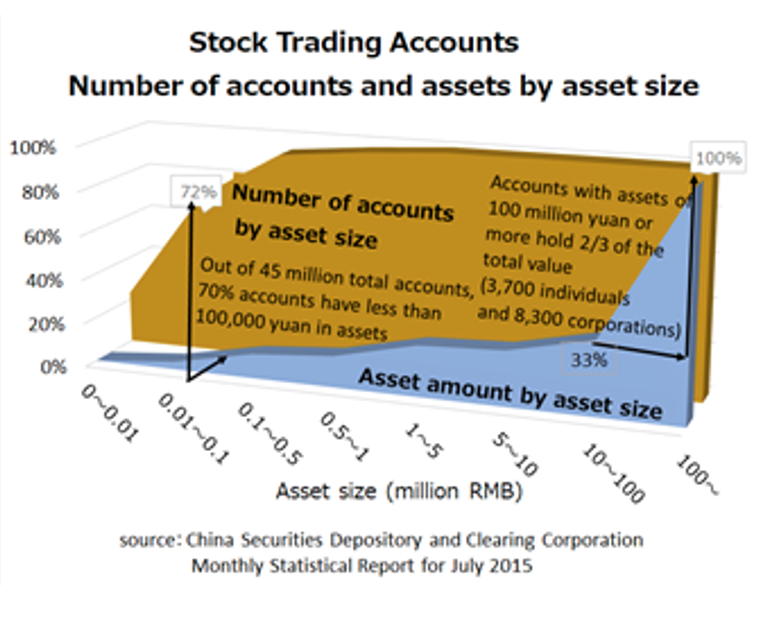

Besides, the chart to the right shows who holds the shares of China’s listed companies and how. Two-thirds of the total market capitalization is held in the stock trading accounts of about 8,300 corporations and about 3,700 individuals, representing only 0.03% of the total accounts. Most of these shareholders are probably state-owned enterprises and red aristocracy individuals (or their agents.)

In short, private enterprises play a major role in terms of flow, but in terms of stock there is a highly skewed distribution of wealth among the government, the privileged, and the wealthy. As a result, there is a striking asymmetry between flow and stock.

The Chinese government utilizes unparalleled financial power derived from this structure. Its ability to mobilize resources was impressively demonstrated in the city of Wuhan in February 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic exploded. The government made an irreversible mistake of hiding the information at the initial stage. However, it built field hospitals within 10 days and expeditiously dispatched tens of thousands of medical staff from all over the country.

The Chinese government is also able to rapidly expand its military; provide "implicit government guarantees" for finance; carry out industrial policies on a scale that no other country can afford; and engage in major science projects, such as entering space as a single country. These are only possible because of the staggering amount of wealth and resources at the government’s disposal.

The CCP boasts such ability as proof of the superiority of its leadership and the Chinese socialist system, but it is also the root cause why we feel “China plays a different game from ours” or “China is alien."

The author thinks, however, there are good and bad sides to everything. While the concentration of wealth in government gives the Chinese government the ability to act powerfully on one hand, it is seriously undermining the health of the Chinese economy on the other.

Conclusion

This paper argues that wealth has been overwhelmingly distributed to the government and the CCP stakeholders in China and that this trend is getting stronger through "unjustifiable wealth transfers" brought about by the absurd scale of the real estate bubble and implicit government guarantee for the financial debt.

If this trend does not change, China will face two serious problems: one political, and the other economic.

Politically, the gap between the rich and the poor will further widen. Young people will lose both their dreams in life and their faith in the rule of the Communist Party. As Xi put it, the "party's ruling base" will be at risk.

Economically, the sustainability of economic growth is at stake. If China wants to sustain its economic growth, the prescription is simple; grow as much as possible the highly productive private sector, especially the new economy, while restructuring and downsizing the old state-owned or state-related sector, which is less productive and financially damaged.

China needs to redirect the fruits of growth from the state-owned sector to the private sector. To do that, it needs to rectify the "unjustifiable wealth transfer" and reduce the state-sector's role. In other words, punishing platform companies and forcing their founders to donate huge sums of money is heading in the wrong direction.

Such reforms will face strong resistance from vested interests. Moreover, it will amount to changing the fundamental shape of the nation. Therefore, Xi and his party would never agree with such reforms unless politically and economically cornered. As a result, China will almost certainly come to face the two major issues previously noted and head toward the middle-income trap.

(2021/12/6)

Notes

- 1 “Xi Jinping presided over the 10th meeting of the Central Finance and Economics Commission, stressing the promotion of common prosperity in high-quality development,” Xinhua News Agency, Aug. 17, 2021. (习近平主持召开中央财经委员会第十次会议强调 在高质量发展中促进共同富裕)(Chinese)

- 2 Xi Jinping called for grasping the new development stage, implementing the new development concept and building a new development pattern at a study session for leading provincial- and ministerial-level cadres. Chinese Government website Jan. 11, 2021. (习近平:把握新发展阶段,贯彻新发展理念,构建新发展格局在省部级主要领导干部研讨班)(Chinese)

- 3 Announcements of donations by IT giants in China (source: media reports)

- Tiktok founder Zhang Yiming to donate 500 million RMB to a local government

- Alibaba to invest 100 billion RMB for "common prosperity" projects, including medical care for farming villages and insurance for delivery workers

- Tencent to pour 100 billion RMB into "social aid" projects

- Meituan founder Wang Xing to donate 17.6 billion HKD to the charity fund he established

- Xiaomi founder Lei Jun to donate 2.2 billion USD to a charity fund

- Pingduoduo founder Huang Zheng to donate 2.2 billion USD and announced he would donate all 1.5 billion USD of next year's projected company profits

- 4 Chairman of SOHO China Shiyi Pan's remarks at the 9th Caixin Summit 2018. (held on November 17, 2018 in Beijing)

- 5 2020 National 50 Cities Home Price to Income Ratio Report, E Home China R&D Institute. (2020年全国50城房价收入比报告,易居研究院)

- 6 Global 80 Cities Rental Yield Study, E Home China R&D Institute (全球 80 城租金收益率研究报告)

- 7 In China, the yield is just over 3% for long-term central government bonds, whose risk is the lowest as the sovereign. The prime loan rate by banks applied only to large state enterprises is 4.5%. Therefore, even at the most conservative estimate, a hypothetical rate of return of 5% is not too high.

- 8

There are three types of public pension systems in China:

- 1) The basic pension insurance for enterprise employees (企业职工基本养老保险),

- 2) The basic pension insurance for public institutions (机关事业单位基本养老保险), and

- 3) The basic pension for urban and rural residents (城乡居民基础养老金).

- 9 IMF Global Financial Stability Report (Apr. 2016)

- 10 “The Grey Rhino in China's Balance Sheet: Local Government Financing Platforms” (中国资产负债表中的“灰犀牛”:地方融资平台) Mar. 28, 2019. Yicai (第一财经)”

- 11 “China Plans Property-Tax Trials as it Targets Speculation” (October, 25th 2021, Wall Street Journal)

- 12 Xi Jinping: Speech at the Symposium with Private Enterprises (习近平:在民营企业座谈会上的讲话) Nov. 1, 2018. Gov. website.