Infection spreading unchecked

The Modi government in India, which won a landslide victory in a general election last year, is facing a major challenge in dealing with the new coronavirus. The problem is not that the government’s response came too late – on the contrary, measures were put in place so quickly that the response was seen as excessive. By mid-March the government had stopped all foreign nationals from entering the country, and a nationwide lockdown was announced on March 25. All of this despite the fact that there were only 536 cases of infection.

India’s lockdown was very strict compared to other countries, but the number of infections has continued to rise[1]. The lockdown was extended three times, and the country finally began a phased reopening in June. By that point, however, the number of infections had reached 190,000. Infections increased with the resumption of economic activity, and as of mid-June India had more than 400,000 cases, the fourth most in the world. Considering India’s massive population of 1.3 billion people, the government’s claims that the spread of infections and deaths are under control relative to the West are accurate. However, the rate of PCR tests per capita is as low as in Japan, and it is thought that there are many more people who are actually infected. Considering the facts that Indian society has no experience with social distancing and the country contains densely populated slums, the effectiveness of the lockdown was naturally limited[2].

Moreover, the lockdown, which continued for more than two months, dealt a major blow to India’s struggling economy. The World Bank lowered its forecast for India’s economic growth in fiscal 2020 to minus 3.2% from 5.8%[3].

Social unrest is now spreading. An alleged cluster at a gathering of Muslims has exacerbated religious tension between Hindus and Muslims, and migrant workers in Delhi, Mumbai and elsewhere have lost their jobs.

The India-China border dispute claims its first victim in 45 years

To complicate the situation, India was then attacked by China, which claims to have “conquered” the coronavirus. As the rest of the world focused on measures to fight the disease, Xi Jinping’s administration grew increasingly assertive in Hong Kong, Taiwan, the East China Sea and the South China Sea, stepping up its military activities.

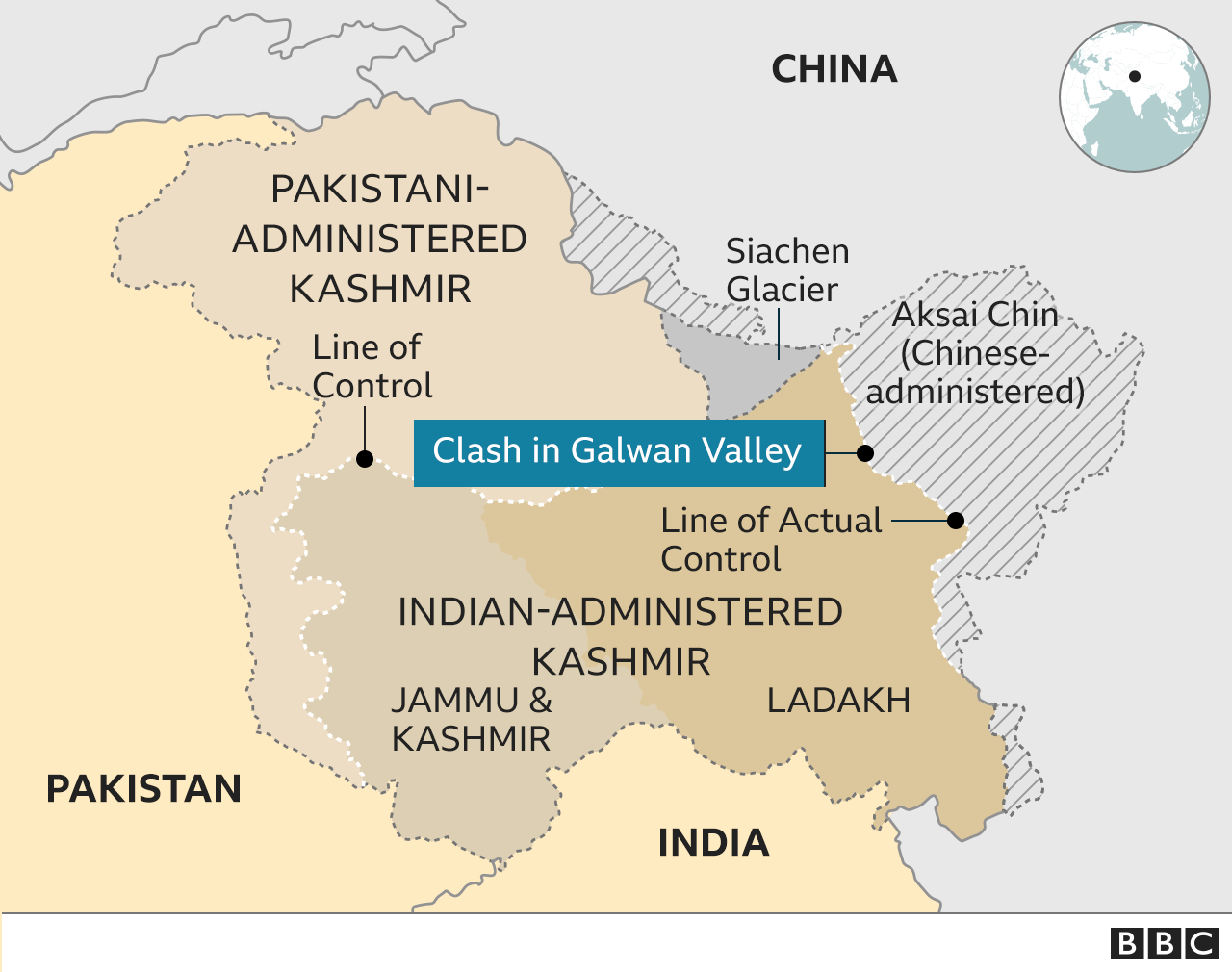

In May it began to do the same along the China-India land border. After the border war of 1962, nearly half of the territorial issues related to the China-India border remain unresolved. The two reached an agreement in 1993 to respect the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and maintain the status quo. After that, a series of confidence-building measures (CBMs) were implemented at multiple levels. As a result, despite occasional skirmishes, standoffs and accusations of “incursions,” India and China have avoided armed conflict and maintained a “managed rivalry[4].” This was a stark contrast to the regular shooting fights and casualties suffered across the Line of Control (LOC) in Kashmir, where India is engaged with its other adversary, Pakistan.

But the clashes between India and China that happened in June resulted in the first deaths in 45 years. First, in early May it was reported that soldiers had engaged in skirmishes, including fistfights, in several places along the LAC in the Indian areas of Ladakh and Sikkim, resulting in injuries on both sides[5]. But this level of “fight” had happened before. Thanks to the CBMs, neither side used weapons, and it was believed that they would resolve the issue and avoid escalation.

Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh made clear his willingness to play down tensions, offering the traditional government stance that such so-called “incursions” were the result of “differences in perception” between the two sides on the alignment of the LAC. He stressed that India was looking for resolution through dialogue. In early June, a series of high-level diplomatic and military talks took place between the two sides, and it was reported that they had agreed to a “partial disengagement” from the front lines[6].

Despite these agreements, however, it appears that in some places the “conflict” on the ground over the “differences in perception” on the alignment of the LAC were so intense as to be inextricable. The incident took place in the Galwan Valley, which is located between Ladakh in India and China-administered Aksai Chin. 20 soldiers died on the Indian side after a clash on the night of June 15 that lasted into the early morning of June 16[7]. Chinese authorities have not released any figures, but it is believed there were also casualties on the Chinese side.

How did such a tragedy happen, even though allegedly no shots were fired? Compiling reports from India, it appears that the clash took place during the withdrawal process. Indian troops were monitoring the Chinese withdrawal when the Chinese soldiers attacked them with stones and sticks, as well as releasing water from a stream that had been dammed. Many soldiers were thrown into a ravine, and search and rescue operations did not start until the next morning. The Galwan Valley is located in the Himalayas at the high altitude of 4,300 meters, and the air temperature approaches freezing even at this time of year. These circumstances are believed to have contributed to the casualties.

Why is China taking the offensive against India now??

Indian experts seem unable to determine the true intentions behind China’s offensive push. Conventional thinking suggests that China would not want to make an enemy of India at a time when it is dealing with a deteriorating relationship with the U.S. – even heading toward a “New Cold War” – over the ongoing trade war, its responsibility for the spread of the coronavirus and the events in Hong Kong. If the border incident further aggravates bilateral relations, it could push India into closer cooperation with Australia, Japan and the U.S. in the “Indo-Pacific Ocean,” leading to a form of “encirclement” around China. Anyone could imagine such developments.

In fact, in the midst of the crisis, Alice Wells, Acting Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asia at the U.S. State Department, said that the Chinese side was the threat in China-India tensions, and there would be great opportunities for India to diversify its supply chains and reduce its reliance on China in the post-coronavirus world[8]. U.S. President Donald Trump also said that he wanted to invite Prime Minister Modi to the G7 summit in the U.S., which had been postponed in fall[9]. Australian Prime Minister Morrison, in a video conference with Prime Minister Modi, elevated his country’s relationship with India to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” The two countries established a two-plus-two ministerial dialogue like that between Japan and the U.S., as well as a mutual logistics support agreement that allows access to each other’s bases.

So why is China pressing the offensive on the border? The root of the issue is a sense of concern on both sides about infrastructure along the LAC. Until recently, India had lagged behind China in road construction, and the Modi government was aggressively pursuing such projects. These roads make it easier to mobilize troops to the front lines in an emergency, and both sides want to prevent the other from building them.

Politically and diplomatically, China joined Pakistan as a party in the dispute about the Modi government’s announcement last summer of the suspension of special constitutional status of Jammu and Kashmir, and the division of the state into two directly governed, Union territories. China protested the move as a “unilateral change of the status quo.” Moreover, there was likely some backlash to the strengthening of the “Australia-India-Japan-U.S.” framework. However, these factors do not explain why China acted “now.”

Former Foreign Secretary Shyam Saran argues that China is motivated by excessive confidence that it will recover quickly from the coronavirus, as opposed to the U.S., which is seeing its power decline. This presents China with an opportunity to expand its influence. Furthermore, China is becoming more assertive out of concern that it could be held responsible for the spread of the coronavirus, and India is no exception to this hardline posture[10]. Happymon Jacob of Jawaharlal Nehru University has suggested that China may be trying to show India and the U.S. that it can withstand U.S. pressure, and that it maintains the means to put pressure of its own on India[11].

While there is no way to say for sure, the dominant view in India is that this was a calculated strategic move by China, and not an “accidental” incident. Anti-China sentiment, including a boycott of Chinese goods, has grown to such an extent that it has drowned out media criticism of the government’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic. The Modi government is expected to step up its “retaliatory measures,” like shutting Chinese companies out of Indian markets.

What should India do??

Looking ahead to the post-coronavirus world, more people are calling for India to strengthen its cooperation with Australia, Japan and the U.S. Harsh Pant, a strategist active in both the U.K. and India, has said that India should side with the democratic countries[12].

But “traditional” ways of thinking are still deeply rooted. M.K. Narayanan and Shivshankar Menon, both of whom served as National Security Adviser in pervious Indian National Congress governments, have predicted that the China-U.S. conflict will get worse. They warn that it is not to India’s benefit to take sides, and that the country should not take the simple path of antagonism toward China[13].

However, whether India can continue to behave as a “swing state” between the U.S. and China and maintain its “strategic autonomy” will depend on if the Modi government can overcome the socio-economic contradictions exposed by the coronavirus crisis and get the country back on a growth trajectory[14]. India is now at a crossroads in dealing with two immediate crises: the coronavirus pandemic and the Chinese offensive.

(2020/09/30)

Notes

- 1 Of the ten countries with legally enforceable lockdowns, India and Russia were the only ones that did not see a decline in the number of new infections after one month. India’s lockdown was the most stringent among those ten countries, according to a study by Oxford University.

Shreya Raman, “Within a Month of Lockdown, New COVID-19 Cases Dipped in 8 Countries, But Not India,” The Wire, May 3, 2020. - 2 Jyoti Shelar, Ajeet Mahale, “Coronavirus in Dharavi | When a virus finds space in India’s largest slum,” The Hindu, May 9, 2020.

- 3 Gaurav Noronha, “India's economy to contract by 3.2 per cent in fiscal year 2020-21: World Bank,” The Economic Times, June 8 2020.

- 4 T.V.Paul,“Explaining Conflict and Cooperation in the China-India Rivalry,” in T.V. Paul ed., The China-India Rivalry in the Globalization Era, Orient Blackswan, 2019, p.6.

- 5 Dinakar Peri, “Indian, Chinese troops face off in Eastern Ladakh, Sikkim,” The Hindu, May 10, 2020.

- 6 “LAC row with China | Efforts on to resolve situation at earliest, says India,” The Hindu, June 11, 2020.

- 7 Dinakar Peri, Suhasini Haidar, Ananth Krishnan, “Indian Army says 20 soldiers killed in clash with Chinese troops in the Galwan area,” The Hindu, June 16.

- 8 “Post-coronavirus world provides window of opportunity to India: Wells,” The Hindu, May 21, 2020.

- 9 Kallol Bhattacharjee, “Donald Trump invites Narendra Modi for G-7 summit in U.S.,” The Hindu,” June 2, 2020.

President Trump, possibly with the intention of working against China and supporting India, also offered to “mediate” between the two sides on Twitter on May 27, and later revealed that Prime Minister Modi had told him that he was worried about relations with China. However, this left the Indian side puzzled. The Indian Ministry of External Affairs completely denied the content of the statement, saying that there had been no contact between Modi and Trump, including phone calls, since the start of the crisis. - 10 Shyam Saran, “China’s aggression against India, Hong Kong, US comes from sense of siege on pandemic origin,” The Print, June 1,2020.

- 11 Happymon Jacob, “In Himalayan staredown, the dilemmas for Delhi,” The Hindu,, June 4, 2020.

- 12 Harsh Pant, “The China challenge: In the evolving geopolitical dynamic after Covid, India should side with democracies,” The Times of India, June 16, 2020.

- 13 M.K. Narayanan ,“Remaining non-aligned is good advice,” The Hindu, June 16, 2020.Nayanima Basu, “Covid-19 different from Tiananmen, China won’t be able to tide over crisis: Ex-NSA Menon,” The Print, May 7, 2020.

- 14 Pranay Kotasthane, Akshay Alladi, Anirudh Kanisetti, and Anupam Manur, “Executive Summary: Takshashila Discussion SlideDoc: India in the Post COVID-19 World Order,” The Takshashila Institution, May 7, 2020.