Active Cyber Defense Bill Clears Lower House

On March 28, 2025, the House of Representatives Cabinet Committee held a hearing on the so-called Active Cyber Defense (ACD) bill.[1] I participated as an expert witness alongside Professor Katsunari Yoshioka of Yokohama National University, Professor Masahiro Kurosaki of the National Defense Academy, and University of Tokyo Visiting Professor (and SPF Senior Fellow) Nobushige Takamizawa.

Following minor revisions, the legislative package passed the House of Representatives on April 8 with support not only from the ruling Liberal Democratic Party and Komeito but also from the Constitutional Democratic Party, the Japan Innovation Party, and the Democratic Party for the People.[2] The package has now been sent to the House of Councillors and is expected to be enacted during the current Diet session.

Japan’s December 2022 revisions to the National Security Strategy (NSS) called for embracing the ACD concept, stating, “Japan will introduce active cyber defense for eliminating in advance the possibility of serious cyberattacks that may cause national security concerns to the Government and critical infrastructures and for preventing the spread of damage in case of such attacks.”[3]

The NSS outlined three areas for building an ACD framework: (1) strengthening public-private cooperation and establishing a support system, (2) using internet communications data (administrative interception), and (3) enabling access and neutralization measures. To pursue these objectives, the Cabinet Secretariat established a Preparatory Office for Cybersecurity Framework Development on January 31, 2023, initiating a comprehensive review of the legal and institutional foundations necessary for ACD.[4]

The first meeting of the Expert Panel on Enhancing Cybersecurity Capabilities was convened on June 7, 2024. In addition to three general meetings, each of the three policy areas—public-private cooperation, communications data use, and access and neutralization measures—was examined in two subcommittee sessions focused on the respective themes.[5]

These discussions were summarized in an interim report released on August 7, outlining both the proposed framework and associated challenges.[6] A final report, titled Recommendations for Enhancing Cybersecurity Capabilities, was released on November 29,[7] identifying four key areas for implementation: (1) strengthening public-private cooperation, (2) use of communications data, (3) access and neutralization measures, and (4) cross-cutting issues.

On the basis of these recommendations, the cabinet approved and submitted the ACD legislation to the Diet on February 7, 2025.[8]

Four Pillars

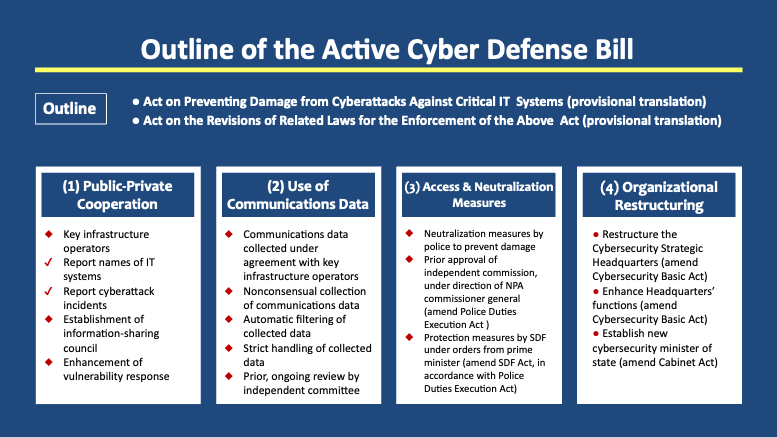

As shown in Figure 1, the ACD legislation rests on four pillars: (1) public-private cooperation, (2) use of internet communications data, (3) access and neutralization measures, and (4) organizational restructuring. The main ACD bill, as outlined by the Cabinet Secretariat, addresses the first two pillars and establishes an independent cyber communications data oversight commission to monitor government ACD activities. This bill will be a stand-alone law consisting of 12 chapters and 86 articles.

A companion bill revises 18 existing laws—including the National Public Service Act, the Police Duties Execution Act, the Self-Defense Forces Act, the Cabinet Act, and the Cabinet Office Establishment Act—to implement the remaining two pillars.

Figure 1. Outline of the ACD Bill

The gist of the four pillars, as summarized by the author based on the text of the bill and outline published on the Cabinet Secretariat’s cybersecurity initiatives page, is as follows:[9]

-

(1) Public-Private Cooperation

A) Reporting Requirements for Key Infrastructure Operators: Critical infrastructure operators will be specified as “designated social infrastructure businesses.” When these businesses introduce IT systems essential to societal functions (“designated critical computers”), they must report them to the relevant minister and prime minister. If such systems are targeted in cyberattacks (“designated intrusion incidents”), reporting is mandatory. Penalties apply for noncompliance.

B) Creation of an Information-Sharing Council: A new council comprising infrastructure providers and IT vendors will facilitate government-industry information exchange on cyber threats. The government may request data from council members, and unauthorized disclosures will be subject to penalties. -

(2) Use of Internet Communications Data

A) Voluntary Sharing of Communications Data: With the informed consent of infrastructure operators, incoming and outgoing communications data to and from them will be collected, analyzed, and used for security purposes. (Informed consent serves to safeguard the constitutional right to the “secrecy of communication.”)

B) Nonconsensual Collection of Cross-Border Data: Internet communications data that cross borders (inbound, outbound, and external-external) may be collected, analyzed, and used without consent, excluding internal-internal communications protected by the “secrecy of communication” clause.

C) Automatic Filtering: Collected data will be automatically filtered to extract only cyberattack-related content, thus minimizing intrusion into private communications.

D) Independent Oversight: An independent “Article 3 commission” (based on the National Government Organization Act) will review data collection in advance, oversee ongoing operations, and report to the Diet.

Although concerns were raised in the Diet regarding potential violations of Article 21 of the Constitution (which protects the secrecy of communication), the provisions described above are designed to protect constitutional rights, and there is no compelling basis for concluding that constitutional infringements would occur. -

(3) Access and Neutralization Measures

A) Police Authority: The commissioner general of the National Police Agency may designate qualified officers as cyberattack response personnel. When a suspected cyberattack is detected in telecommunications, and immediate action is deemed necessary to prevent serious harm, these officers may access compromised systems, identify malware, and neutralize threats. Such measures require prior approval from an independent telecommunications information oversight commission, except in emergencies where ex post facto notification is permitted. If foreign systems are involved, prior consultation with the minister for foreign affairs is required.

B) SDF Authority: In the event of a sophisticated attack by a foreign entity on government or critical infrastructure systems, the prime minister may designate the attack as a “specified incident” and authorize the Self-Defense Forces (SDF) to respond, subject to approval from the National Public Safety Commission and an independent telecommunications information oversight commission (ex post facto notification being permitted, again, in emergency cases). The SDF may then collaborate with the police to neutralize threats. The same authority extends to attacks targeting SDF systems or those of the US military in Japan. -

(4) Organizational Restructuring

A) Strengthening the Cybersecurity Strategic Headquarters: The headquarters will be restructured under the direct leadership of the prime minister, with all cabinet ministers serving as members.

B) Expanded Functions: The headquarters will set national cybersecurity standards for critical infrastructure operators and assess the effectiveness of cybersecurity measures taken by government agencies.

C) Establishment of a Cabinet Cybersecurity Officer: A new administrative vice-minister-level officer will oversee cybersecurity policy within the Cabinet Secretariat.

D) Establishment of a New Ministerial Post: A minister of state for cybersecurity will be appointed within the Cabinet Office to oversee public-private cooperation and communications data usage.

Toward Persistent Cyber Engagement

The enactment of the ACD legislation is only the beginning. Japan must henceforth engage in an ongoing, 24/7 battle against cyber adversaries, including those backed by foreign governments. This approach aligns with the US doctrine of “persistent engagement,” introduced in the 2018 National Cyber Strategy during the first Donald Trump administration.[10]“Persistent engagement” involves constant interaction with hostile cyber actors, while the related doctrine of “defend forward”—outlined in the Department of Defense Cyber Strategy—seeks to disrupt threats within the territory of adversaries.[11] These concepts remained central to US cyber strategy through the Joe Biden administration, and the 2023 Cyber Strategy of the Department of Defense affirms the continuation of this approach, stating that the Defense Department “will continue to persistently engage US adversaries in cyberspace, identifying malicious cyber activity in the early stages of planning and development.”[12]

Once implemented, Japan’s ACD strategy will likewise require real-time surveillance of domestic cyberspace, early identification of hostile attackers, and lawful deployment of preemptive and responsive countermeasures across networks and borders to contain breaches before they escalate.

Japan’s traditional cybersecurity posture has emphasized passive defense focused on fortifying domestic systems by erecting firewalls, using anti-virus software, monitoring and scanning for malware, and patching vulnerabilities. In military terms, this can be likened to trench warfare or a siege: fortifying one’s position with deep moats or high walls and repelling intrusions from unknown directions.

By contrast, ACD resembles mobile defense tactics: identifying enemy patterns, launching surprise countermeasures before a strike, cutting off supply lines, and exploiting vulnerabilities. It emphasizes disruption over defense aimed at increasing the technical and operational costs of aggression.

Tactics may include honeypots to identify stolen files, digital watermarks to enable remote tracking, redirecting malware traffic to controlled servers, and feeding attackers misleading data. In some cases, more aggressive technical responses may be warranted, such as remotely disabling attacker-controlled systems or launching DDoS (distributed denial of service) counterattacks to overwhelm and incapacitate such systems.

Nontechnical policy tools can also play a vital role in responding to foreign launched cyberattacks. They include public disclosures of attack methods, public attribution (identifying and calling out attackers) in coordination with partner countries, diplomatic protests, legal action, and financial or economic sanctions.

Building a Cross-Domain Security Concept

As described above, active cyber defense is aimed at ensuring national security and differs fundamentally from conventional cybersecurity. ACD includes not just technical responses but also intelligence-driven and potentially military-aligned operations when cyberattacks are assessed to have military objectives. As such, it demands a new generation of personnel trained not only in the latest technology and cybersecurity but also in national security strategy and operational planning.

Japan’s ACD strategy will involve strengthening public-private cooperation and establishing support systems. Select private-sector actors with security clearance will receive sensitive information from government sources, including intelligence from foreign partners and undisclosed countermeasures and vulnerabilities. Infrastructure providers and cybersecurity firms will need cleared personnel with national security expertise.

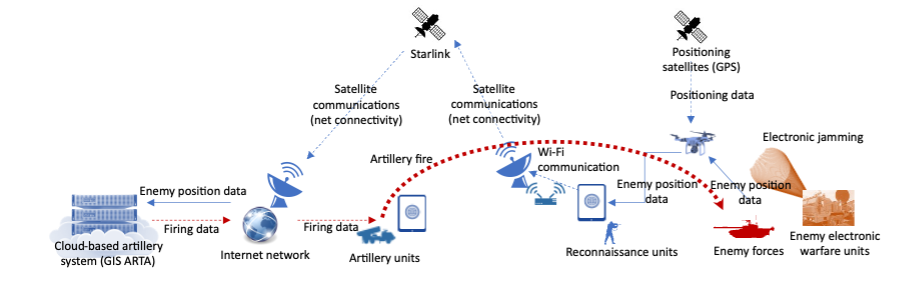

The scope of cybersecurity has evolved from protecting individual devices to safeguarding networks and, now, to securing cyberspace in the national interest. Today’s threats include hybrid warfare and cognitive warfare (information operations targeting public perception), both of which call for cross-domain, cyber-integrated responses (Figure 2). Cross-domain warfare, spanning cyberspace, outer space, and the electromagnetic spectrum, demands agility in adapting to rapid technological change.

For instance, digital transformation is accelerating cloud adoption. From a security standpoint, this necessitates securing data integrity and building sovereign cloud systems—secure, domestically governed environments for sensitive data.

Figure 2. Cross-Domain Operations in Emerging Domains

Technological advances, especially in AI, require a comprehensive framework that links emerging capabilities across domains. Japan must urgently articulate a cross-domain security concept that maps out these interrelationships and guides the development of strategic capabilities.

To make this vision a reality, a conceptual framework must be outlined and strategic goals laid out in five- and ten-year roadmaps. Baseball superstar Shohei Ohtani is famously said to have used a mandala-style chart to visualize the steps needed to achieve his goals.[13] Similarly, realizing complex national security objectives will require visual planning tools to incrementally enhance each operational capability. A clearly defined roadmap is essential.

With these needs in mind, the Sasakawa Peace Foundation is preparing to launch a comprehensive research program focused on active cyber defense, with the aim of helping develop a cross-domain security strategy for the future.

(2025/06/23)

Notes

- 1 “‘Nodoteki saiba bogyo’ donyu hoan: Shuin naikakui de sankonin shitsugi” (Diet Committee Hears Expert Testimony on Bill to Introduce ‘Active Cyber Defense’), NHK News, March 28, 2025.

- 2 “‘Tsushin no himitsu’ shingai wa? Kanrii no arikata wa? Saiba bogyo meguri ronsen” (Does It Violate the ‘Secrecy of Communications’? How Should the Oversight Commission Function? Debates Over Cyber Defense), Mainichi Shimbun, March 18, 2025.

- 3 Cabinet Secretariat, National Security Strategy of Japan, December 2022, p. 23.

- 4 “‘Nodoteki saiba bogyo’ junbishitsu, Naikakufu ni shinsetsu: Seifu” (Preparatory Office for ‘Active Cyber Defense’ Established in the Cabinet Secretariat: Government), Nihon Keizai Shimbun, January 31, 2023.

- 5 Cabinet Secretariat, “Saiba anzen hosho bunya de no taio noryoku no kojo ni muketa yushikisha kaigi” (Expert Panel on Enhancing Capabilities in the Field of Cybersecurity), accessed March 31, 2025.

- 6 Cabinet Secretariat Cybersecurity Policy Office, “Saiba anzen hosho bunya de no taio noryoku no kojo ni muketa yushikisha kaigi: Koremade no giron no seiri” (Summary of Discussions to Date by the Expert Panel on Enhancing Capabilities in the Field of Cybersecurity), August 7, 2024.

- 7 Expert Panel on Enhancing Capabilities in the Field of Cybersecurity, “Saiba anzen hosho bunya de no taio noryoku no kojo ni muketa teigen” (Recommendations for Enhancing Cybersecurity Capabilities), November 29, 2024.

- 8 “Kogeki-moto ni akusesu shi mugaika ‘nodoteki saiba bogyo’ hoan kakugi kettei” (Cabinet Approves Bill on ‘Active Cyber Defense’ Allowing Access to Source of Attacks for Neutralization), NHK News, February 7, 2025.

- 9 Cabinet Secretariat, “Saiba anzen hosho ni kansuru torikumi” (Cybersecurity Initiatives).

- 10 The White House, National Cyber Strategy of the United States of America, September 2018.

- 11 US Department of Defense, Department of Defense Cyber Strategy, September 2018.

- 12 US Department of Defense, 2023 Cyber Strategy of the Department of Defense, September 2023.

- 13 Akio Morita, “Otani-san no mandara chato” (Ohtani’s Mandala Chart), accessed April 14, 2025.