Japan and the Philippines have long enjoyed a close and friendly relationship, but in recent years their defense ties have also grown much stronger.[1] The second Japan-Philippines Foreign and Defense Ministerial Meeting (2+2), held on July 8, 2024, was noteworthy for the signing of a bilateral Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) and confirmation of continued and strengthened cooperation on defense equipment and technology and official security assistance (OSA).

Japan provided the Philippines with an FPS-3ME advanced air surveillance radar system in October 2023[2] and a TPS-P14ME mobile air surveillance radar system in April 2024. These marked the first provisions of equipment following the 2014 revision of Japan’s Three Principles on the Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology. Japan plans to provide two more radar systems for a total of four sets.[3] And with additional transfers of other equipment expected through OSA,[4] the bilateral security relationship, at least in equipment terms, will certainly grow stronger in the coming years.

The air surveillance radars are expected to significantly boost the Philippine’s air domain awareness (ADA) capabilities in the South China Sea, where China continues to attempt to change the status quo by force. For Japan, the air surveillance radars represent not only the first cases of transferring finished equipment under the revised Three Principles but also the potential to create an ADA network extending approximately 3,000 nautical miles from the Japanese archipelago to the Philippines—if the two countries’ ADA systems can be linked in the future. This will make China’s air power projection intentions in the Pacific more transparent.

In the following, I will examine the potential and significance of linking the Japanese and Philippine ADA systems. First, I will outline China’s current air power projection activities and then review the significance of Taiwan’s early warning system for Japan’s ADA, pointing out that while Taiwan has outstanding ADA capabilities, the chances of linking the Japanese and Taiwanese systems at this point are low. I will then argue that providing air surveillance radars to the Philippines and ultimately linking them to the ADA system in Japan is next best alternative.

Sharp Rise in Emergency Takeoffs since 2005

According to a report by the Joint Staff Office of the Ministry of Defense, the scrambling of Air Self-Defense Force (ASDF) fighter jets decreased rapidly from fiscal 1989 (when targets were mostly former Soviet military aircraft), and cases hovered around 200 times per year for 10 years from fiscal 1995. There has been a sharp upturn since fiscal 2005, however, this time against Chinese military aircraft.[5]

In fiscal 2003, fighters were scrambled against Chinese aircraft just two times. Emergency takeoffs rose sharply thereafter, reaching 306 in fiscal 2012 (Chinese aircraft accounted for 54% of the total) and 851 in fiscal 2016 (73%). The total number of scrambles during that year was 1,168, the highest figure since the ASDF began deploying fighters to counter airspace violations in 1958.[6] Takeoffs against Chinese planes have fluctuated since then, averaging around 600 per year in the 10 years up to fiscal 2023.

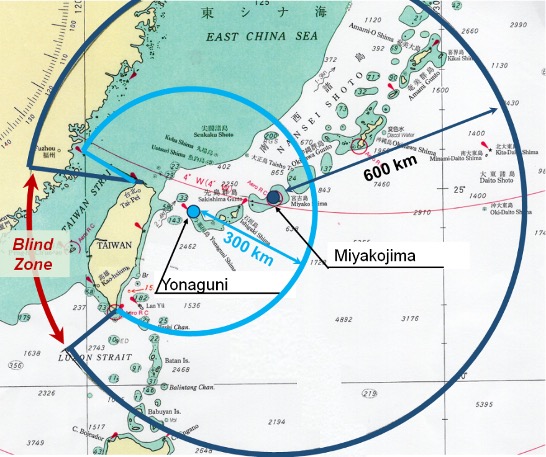

One of the challenges for the ASDF is that the range of mountains over 3,000 meters above sea level in eastern Taiwan creates a radar blind zone, hindering the effective detection of Chinese military activity. The 53rd Warning Squadron has a stationary J/FPS-7 radar on the island of Miyakojima (with a maximum altitude of 113 meters) and a mobile J/TPS-102 radar on the island of Yonaguni (231 meters), but they are unable to detect activities in the western airspace of Taiwan. The ASDF can access information from air traffic control radars operated by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism, but there still remain blind spots.

Although the maximum detection range of the J/FPS-7 has not been publicly disclosed, if we assume that it is equivalent to that of the J/FPS-3 (maximum 351 nautical miles),[7] we can probably conclude that it covers up to the southern tip of Taiwan. Still, constraints of the radar blind zone and radar horizon could mean detection and response delays for small, low-altitude Chinese aircraft flying counterclockwise around Taiwan via the Bashi Channel.

Figure 1. Blind Zone from Radars on Miyakojima and Yonaguni

The activities of Chinese military aircraft in the East China Sea have been expanding eastward since 2003. On October 25, 2013, two Y-8 early warning aircraft and two H-6 bombers made a round-trip flight over the Pacific Ocean via the Miyako Strait for the first time.[8] Since then, the number of round trips by Chinese military aircraft over the Pacific Ocean has increased. On November 25, 2016, two H-6 bombers, one TU-154 intelligence-gathering aircraft, and one Y-8 aircraft flew eastward over the Bashi Channel, turned north, and entered the East China Sea through the Miyako Strait.[9] And on July 20, 2017, two H-6 bombers circumnavigated counterclockwise and two of the same type of aircraft flew clockwise as if enveloping the main island of Taiwan from east to west.[10]

Chinese military air activities have further expanded since around 2021 in terms of both airspace and type of aircraft. On August 25, 2021, for example, a BZK-005 reconnaissance drone made a roundtrip flight across the Pacific Ocean alongside a Y-9 intelligence-gathering aircraft, becoming the first unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) to make such a journey.[11]

The radar cross section of China’s UAVs is thought to be equivalent to that of non-stealth fighter jets,[12] making them difficult to detect over long distances. The use of such drones also opens the possibility of an unforeseen incident should the unmanned aircraft be on a fully autonomous flight—even if temporarily—without control from the ground.

Incursions into Taiwan’s ADIZ Published Online since 2020

In September 2020, the website of Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense began publishing information on Chinese military activities in Taiwan’s air defense identification zone (TADIZ). And the Republic of China Air Force (Taiwan Air Force) has been releasing online flight track maps of TADIZ intrusions since March 1, 2022. The first report of Chinese aircraft entering Japan’s ADIZ (JADIZ), according to these sources, occurred on April 7, 2022. A J-11 fighter jet and a Y-8 electronic warfare aircraft entered the TADIZ to the west of Taiwan’s main island and turned back, while a Y-9 electronic warfare aircraft flew through the Bashi Channel along the southern and southeastern edges of the TADIZ, reaching an area south of Miyakojima before retracing its flight path back to China.[13]

On the same day, according to a report by Japan’s Joint Staff Office, a Chinese Y-9 electronic warfare aircraft was confirmed flying in the Pacific, prompting the scrambling of fighter jets by the Southwestern Air Defense Force. The track chart shows the Y-9 moving east over the sea south of Yonaguni before turning around and reentering the TADIZ.[14] Considering the time it takes to launch fighter jets, the Chinese aircraft must have been spotted by radar sites much earlier. But because of the blind zone that the island of Taiwan presents, the radars probably could not determine where the Y-9 aircraft came from and to where it returned; and in all likelihood, they were unable to detect the J-11 and Y-8 flying west of Taiwan.

Another example of the limitations of Japan’s radars is the April 28, 2023, flight of Chinese UAVs that was detected by Taiwan but not fully by Japan. The Joint Staff Office announced the flight of “one (presumed) Chinese UAV” from the Pacific passing between Yonaguni and Taiwan and reaching the East China Sea.[15] Taiwan’s announcement on the same day cited a TB-001 unmanned combat and reconnaissance aerial vehicle flying east through the Bashi Channel and circling Taiwan in a counterclockwise direction and a separate BZK-005 type reconnaissance drone flying along the same path as the TB-001.[16] When comparing the disclosed flight track information, the “presumed Chinese UAV” in the Japanese announcement can be considered the TB-001, while the fact that one (presumed) UAV was actually two aircraft (the other was the BZK-005) went undetected by Japan.

And again, on August 25, 2023, the ASDF reported detecting a BZK-005 reconnaissance drone and a “presumed Chinese UAV” flying in an eastward direction west of the Senkaku Islands and heading south toward the strait between Taiwan and Yonaguni.[17] The “presumed Chinese UAV” was likely a TB-001, which was cited in the report issued by the Taiwan Air Force the following day. The Taiwan Air Force also mentioned a Y-8 anti-submarine aircraft flying in the same airspace as the drones, although this was not listed in the Japanese report.[18]

Taiwan’s Superior Early Warning Capabilities

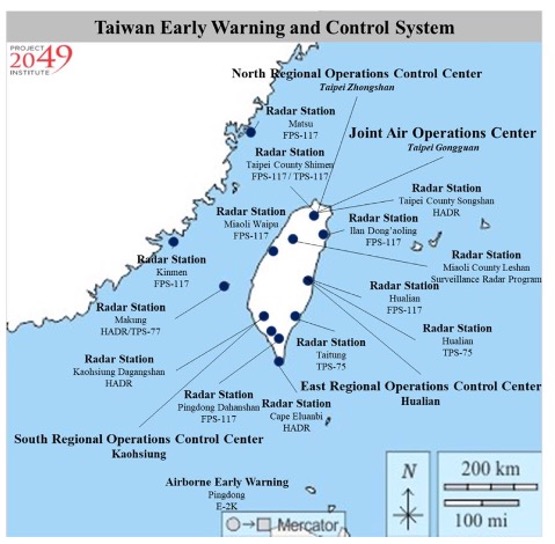

Taiwan has a robust early warning radar network to counter airborne threats from the mainland. First, to detect China’s ballistic missiles launches, it has a Surveillance Radar Program (SRP) installed atop 2,500-meter Mount Leshan in Hsinchu County, about 70 kilometers southwest of Taipei, and it has been active since 2013.[19] The SRP is based on the PAVE PAWS AN/FPS-115 radar with a maximum detection range of 3,000 nautical miles (5,556 kilometers),[20] and its two radar faces cover an azimuth angle of 240 degrees. Unlike the PAVE PAWS in the United States, the SRP can detect airbreathing threats like cruise missiles,[21] and it provides detection information to the United States.[22]

The SRP’s blind zone is covered by long-range air search radars, such as the AN/FPS-117. Taiwan has 11 AN/FPS-117 radars (7 stationary and 4 mobile) with a maximum detection range of approximately 300 kilometers,[23] 4 AN/TPS-75 radars with a maximum detection range of 445 kilometers,[24] and 2 HADR radars with a measured range of 574 kilometers (one each on the islands of Kinmen and Matsu).[25] More than 10 other early warning radars are deployed along the coast of Taiwan’s main island.[26]

The Japanese island of Kyushu, which is about the same size as Taiwan, hosts only five radar sites: at Mount Sefuri and Mount Takahata on the main island and three more on the offshore islands of Fukue, Shimokoshiki, and Uni. This suggests that Taiwan boasts a multi-layered and multiplex early warning network.

Lack of Air Information Exchange between Japan and Taiwan

Japan’s blind zone can be remedied if its ADA network could be linked with that of Taiwan. But defense exchange between Japan and Taiwan has been suspended since diplomatic ties were severed on September 29, 1972. Bilateral exchange has continued only at the non-governmental and business levels.

As a result, the only airspace information that Japan and Taiwan share is what is published online, but such information is not available on a real-time basis. While it can be used for strategic-level analysis of the Chinese military, it cannot provide any early warning that is crucial for the scrambling of fighter jets.

In addition, the standards and timing of disclosures by Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense and Air Force regarding aircraft models and flight routes are different from those of Japan’s Joint Staff Office. Taiwan sometimes releases two days’ worth of information at once or may wait until the next day to disclose facts. The Joint Staff Office reported on August 28, 2023, for example, that China’s BZK-005 reconnaissance drone flew from the East China Sea and passed between Yonaguni and Taiwan’s main island to reach the Pacific, before flying off toward the Bashi Channel,[27] but the Taiwanese Air Force did not announce this until the following day.[28] There was a time when Taiwan did not announce the flights of Chinese military drones,[29] and since January 17, 2024, it has been publishing just the area of their activity rather than the flight path, perhaps due to the recent sharp increase in the number of Chinese military aircraft entering Taiwan’s ADIZ. The value of such information has consequently declined.[30]

Figure 2. Taiwan’s Early Warning and Control System

Strategic Value of Radars in the Philippines

Japan has two ways of sidestepping its lack of access to Taiwan’s ADA network. The first is to obtain Taiwan’s data via the United States. Taiwan’s air defense system was developed in the 1950s in line with the then Mutual Defense Treaty between the United States and the Republic of China. And Washington has continued to support Taipei even after cutting diplomatic ties in 1979. The sale of the SRP radar system was supported by both the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush administrations in the hope that it would hasten the detection of ballistic missile launches by the Chinese military.[31] Taiwan currently provides information from the SRP to the United States. And it is possible that Washington, in providing other air surveillance radars and the E-2C Hawkeye 2000 airborne early warning aircraft to Taiwan, asked Taipei to furnish information from those systems as well. Even if such data were shared between the United States and Taiwan, however, it would be difficult for Japan to gain access to them without the permission of the Taiwanese authorities in the absence of confidential information protection arrangements between Japan and Taiwan.

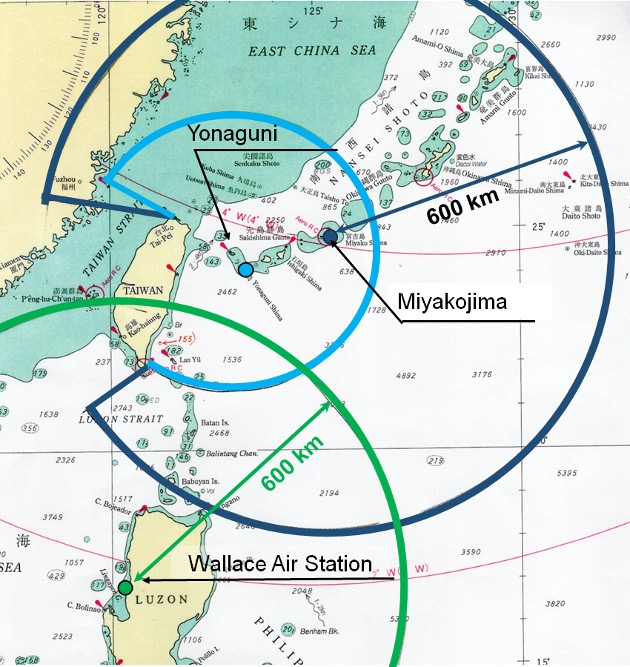

Figure 3. Overlapping Coverage Areas of Japanese and Philippine Radars

The second option is to use the information gathered by the air surveillance radar systems that Japan is providing to the Philippines. The FPS-3ME offered to the Philippines in October 2023 has been installed at the former Wallace Air Station, 200 kilometers north-northwest of Manila. Assuming its detection range is equivalent to that of the ASDF’s J/FPS-3, it will be able to catch activities about 600 kilometers away. This, as shown in Figure 3, means being able to cover airspace up to the southern end of Taiwan. And since the coverage area overlaps slightly with that of the J/FPS-7 on Miyakojima, the sharing of information—while not eliminating the blind zone west of Taiwan—is expected to enhance the detection of Chinese military aircraft passing through the Bashi Channel and moving northeast. And if the Philippine military deploys the mobile TPS-14ME (and two additional radar sets to be provided henceforth) further north, air domain awareness of the Bashi Channel will be further strengthened.

The Japanese and Philippine air defense systems can technically be linked. The remaining hurdle is to conclude a diplomatic arrangement for information sharing similar to the Japan–South Korea General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA). Given the shared threats from China’s aggressive attempts to change the status quo in the East and South China Seas, Japan and the Philippines, during their July 8, 2024, 2+2 meeting, reached agreement on upgrading their security partnership.[32] The conclusion of a GSOMIA agreement may thus be a matter of time.

Conclusion

Linking the ADA networks of Japan and the Philippines can create a radar barrier stretching for around 3,000 nautical miles from the Japanese archipelago to the island of Luzon. Chinese attempts at air power projection in the Pacific through the Miyako Strait, Yonaguni Strait, or Bashi Channel will thus be detected by Japanese and Philippine surveillance and control radars, making the intentions of Chinese military aircraft in the East and South China Seas more transparent.

The complete elimination of ADA blind zones, though, requires the participation of Taiwan in one form or another. The Japanese government should do what it can to pursue this possibility with the goal of realizing seamless anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities against China.

(2024/09/18)

Notes

- 1 High-level exchange, which had been conducted an average of twice a year, was held five times in 2022, twice in 2023, and seven times through July in 2024. Exchange has become more substantive, being upgraded beyond the level of friendship and goodwill. High-level exchange refers to dialogue involving Japan’s minister of defense, vice-minister of defense, parliamentary vice-minister of defense, administrative vice-minister of defense, vice-minister of defense for international affairs, or chiefs of staff. Ministry of Defense, “Firipin hai-reberu koryu” (High-Level Exchange with the Philippines), accessed July 8, 2024.

- 2 “Japan turns over air surveillance radar system to PAF,” Philippine News Agency, December 20, 2023.

- 3 “Firipin ni keikai kansei reda, boei fuku daijin ga shikiten shusseki” (Philippines to Receive Air Surveillance Radars; Vice-Minister of Defense Attends Ceremony), Nihon Keizai Shimbun, April 29, 2024.

- 4 The Japanese government agreed to provide the Philippines with a coastal surveillance radar system on November 3, 2023, in the first case of equipment transfer under OSA. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Firipin Kyowakoku ni taisuru engan kanshi reda shisutemu kyoyo” (Signing and Exchange of Notes on Provision of Coastal Surveillance Radar System to the Republic of the Philippines (OSA)), November 3, 2023.

- 5 Joint Staff Office, “Heisei 24-nendo no kinkyu hasshin jisshi jokyō ni tsuite” (Status of Emergency Takeoffs in Fiscal 2012), April 17, 2013.

- 6 Joint Staff Office, “Heisei 28-nendo no kinkyu hasshin jisshi jokyō ni tsuite” (Status of Emergency Takeoffs in Fiscal 2016), April 13, 2017.

- 7 Values are for a maximum range of 351 nautical miles (650 kilometers) and a target altitude of 20,000 meters. Janes C4ISR & Mission System Land 2022-2023, Janes Information Group, September 2022, p. 942.

- 8 Joint Staff Office, “Chugoku-ki no Higashishinakai ni okeru hiko ni tsuite” (Regarding Flights of Chinese Aircraft in the East China Sea), October 25, 2013.

- 9 Joint Staff Office, “Chugoku-ki no Higashishinakai ni okeru hiko ni tsuite” (Regarding Flights of Chinese Aircraft in the East China Sea), November 25, 2016.

- 10 Joint Staff Office, “Chugoku-ki no Higashishinakai ni okeru hiko ni tsuite” (Regarding Flights of Chinese Aircraft in the East China Sea), July 20, 2017.

- 11 Joint Staff Office, “Chugoku-ki no Higashishinakai oyobi Taiheiyo ni okeru hiko ni tsuite” (Regarding Flights of Chinese Aircraft in the East China Sea and the Pacific Ocean), August 25, 2021.

- 12 The radar cross section of the GJ-1 unmanned reconnaissance aircraft, which is smaller than China’s TB-001 combat and reconnaissance aircraft, is thought to be less than 1 m2, the same as that of a non-stealth fighter. Lieutenant Colonel Andre Haider, GE, “The Vulnerabilities of Unmanned Aircraft System Components,” Joint Air Power Competence Center, January 2021.

- 13 Republic of China Air Force, “Air activities in the southwestern ADIZ of R.O.C.,” April 7, 2022.

- 14 Joint Staff Office press release, “Chugoku-ki no doko ni tsuite” (Regarding Movements of Chinese Aircraft), April 7, 2022.

- 15 Joint Staff Office press release, “Suitei Chugoku-ki no doko ni tsuite” (Regarding Movements of Presumed Chinese Aircraft), April 28, 2023.

- 16 Republic of China Air Force, “PLA activities in the waters and airspace around Taiwan, April 28, 2023.”

- 17 Joint Staff Office press release, “Chugoku-ki no doko ni tsuite” (Regarding Movements of Chinese Aircraft), August 25, 2023.

- 18 Republic of China Air Force, “PLA activities in the waters and airspace around Taiwan, Aug. 26, 2023.”

- 19 Lo Tien-pin and Jonathan Chin, “Radar costs to reach NT$2.39bn,” Taipei Times, September 4, 2024.

- 20 This is the capacity of the AN/FPS-132, a type similar to the SRP. Janes C4ISR & Mission System Land 2022–2023, p. 1238.

- 21 Mark Stokes and Eric Lee, “Early Warning in the Taiwan Strait,” Project 2049 Institute, April 12, 2022.

- 22 Su Zhizong, “Guófáng yuàn: Yàoshān léidá zhàn fànwéi hángài nánhǎi gōng měi zǎoqí yùjǐng” (National Defense Academy: Leshan Radar Station Covers the South China Sea, Providing Early Warning to the United States), Central News Agency, November 29, 2020.

- 23 The stationary AN/FPS-117(E)1 has a maximum range of 288 kilometers, while the mobile AN/TPS-77 has a maximum range of 300 kilometers. Janes C4ISR & Mission System Land 2022–2023, pp. 1235–1236.

- 24 Ibid., pp. 965–966.

- 25 “Land & Sea-Based Electronics Forecast Archived Report: HADR (HR-3000)—Archived 7/98,” Forecast International, July 1997.

- 26 Mark Stokes and Eric Lee, op. cit.

- 27 Joint Staff Office press release, “Chugoku-ki no doko ni tsuite” (Regarding Movements of Chinese Aircraft), August 28, 2023.

- 28 Republic of China Air Force, “Flight paths of PLA aircraft, August 29, 2023,” August 29, 2023.

- 29 Examples of Chinese UAV incursions into Tawain’s ADIZ that were reported by Japan but not by Taiwan include press releases in 2022 by the Joint Staff Office on July 25, August 5, and August 30.

- 30 Republic of China Air Force, “PLA activities in the waters and airspace around Taiwan Jan. 17, January 17, 2024”.

- 31 Mark Stokes and Eric Lee, op. cit.

- 32 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Dai 2-kai Nichi-Firipin gaimu boei kakuryo kaigo (‘2 + 2’)” (Second Japan-Philippines Foreign and Defense Ministerial Meeting (2+2)), July 8, 2024.