Introduction

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Western countries have pursued a policy of energy de-Russification. In June 2024, the European Union (EU) adopted its 14th round of sanctions against Russia, moving for the first time to restrict imports of Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG).[1] These sanctions prohibit the transshipment of Russian LNG within the EU for the purpose of re-export to third countries.[2] While not an embargo on Russian natural gas, they are expected to put a stop to imports of Russian gas by EU member states.

During the Ukraine crisis, European natural gas procurement has been supported by the U.S. U.S. LNG has become the foundation of the energy security relationship between the U.S. and Europe, and has also become strategically important for their Asian allies. This paper discusses the strengths of U.S. LNG and examines the implications for the U.S. LNG industry of developments in climate change measures. These measures will also be influenced by the outcome of the November presidential election.

Becoming the World’s Largest LNG Exporter

The U.S. dramatically increased shale gas production in the 2010s through improved drilling technology, and began exporting LNG in February 2016. The LNG export process requires approval from two government agencies under the Natural Gas Act. The first is Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approval for the siting, construction, and operation of LNG export facilities. The second is the Department of Energy (DOE) approval related to LNG exports. Under the DOE’s export review process, applications to export LNG to U.S. Free Trade Agreement (FTA) countries are considered to be in the public interest and are automatically approved. In the case of non-FTA countries, on the other hand, the DOE makes a decision after determining whether the export proposal is consistent with the public interest in economic and environmental terms.[3] DOE environmental reviews typically use environmental impact assessments completed by FERC in accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act as the basis for determining public interest.[4]

The lengthy time required to screen exports to non-FTA countries meant that when U.S. exports began in 2016, U.S. LNG exports were mainly to Latin American countries with which the U.S. had concluded FTAs. Export destinations were then progressively expanded to include Asian countries. During the Ukraine crisis, the DOE has approved more LNG export applications to Europe than ever before as part of U.S.-European energy cooperation. In March 2022, approval was given for exports from the LNG export facility operated by Cheniere Energy to countries across all of Europe, including non-FTA countries.[5] With the expansion of export markets, U.S. LNG exports reached a record 84.5 million tons in 2023,[6] making the it the world's largest LNG exporter, surpassing Australia (79.6 million tons) and Qatar (78.22 million tons).

Strengths of the U.S. LNG Industry

The strengths of the U.S. LNG industry include flexible contractual arrangements, supply- and demand-based pricing, and the country’s geographical advantages. In the case of LNG exports from the Middle East and Southeast Asia, the majority of contracts are long-term sales contracts of around 20 years, and the LNG sales price is linked to the price of crude oil. Destination restrictions are also imposed that prohibit the resale of LNG to third countries. On the other hand, the price structure for U.S. LNG is based on the wholesale price at the Henry Hub, the natural gas hub in Louisiana, and includes liquefaction and other costs. Henry Hub-linked prices depend on gas supply and demand conditions, but tend to be lower than oil price-linked prices, making U.S. LNG relatively cheaper. U.S. LNG companies allow short-term as well as long-term contracts, and there are no restrictions on destination. In this regard, U.S. LNG exporters have the advantage of being able to procure LNG and freely change export destinations in response to increases or decreases in gas market supply and demand.

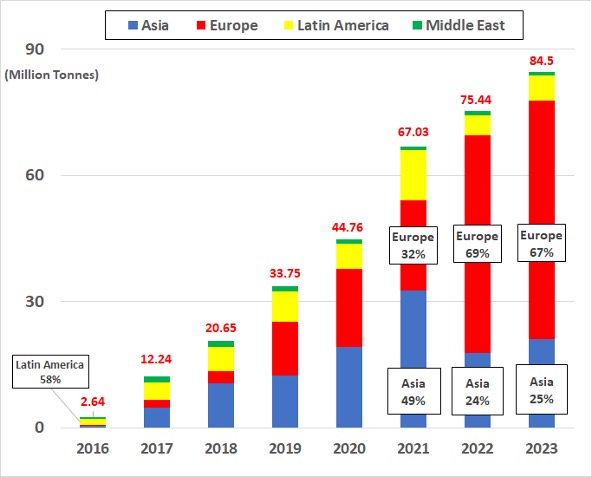

In addition to the benefits of lower prices and resale, the U.S. is well positioned to export LNG to various regions. By region, Latin America accounted for 58% of all U.S. LNG exports in 2016, and Asia recorded the highest percentage of 49% in 2021. Over the past two years, however, the proportion of exports to Europe has reached almost 70%. U.S. LNG stands out in terms of its accessibility to all markets (Figure 1).

This is because the U.S. can avoid maritime chokepoints, which pose significant navigational concerns, when exporting LNG to various regions. LNG shipments from the Middle East to Europe normally have to pass through the Suez Canal. However, maritime attacks by the Houthis in Yemen, which have become more active in conjunction with the worsening situation in Gaza since October 2023, are posing a risk to shipping routes through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal. In addition, exports to major LNG consuming countries in East Asia from the Southeast Asian region must also pass through the Strait of Malacca and the South China Sea, which are potential navigation risks.[7]

By contrast, the U.S. is adjacent to Europe across the Atlantic Ocean and can easily transport energy to Europe. In addition, it can deliver LNG to East Asia unhindered by crossing the Pacific Ocean, notwithstanding the issue of passing through the Panama Canal.[8] Given the reduced risk of supply disruptions, U.S. LNG exports will contribute significantly to securing energy stability for allies in Europe and Asia.

Figure 1: Percentage of U.S. LNG exports by region

Plans to Expand LNG exports

Currently, the Ukraine crisis has meant that exports of U.S. LNG are mainly directed to Europe. However, with the expansion of U.S. LNG export volumes planned, Asian countries are expected to be able to import more in the future.

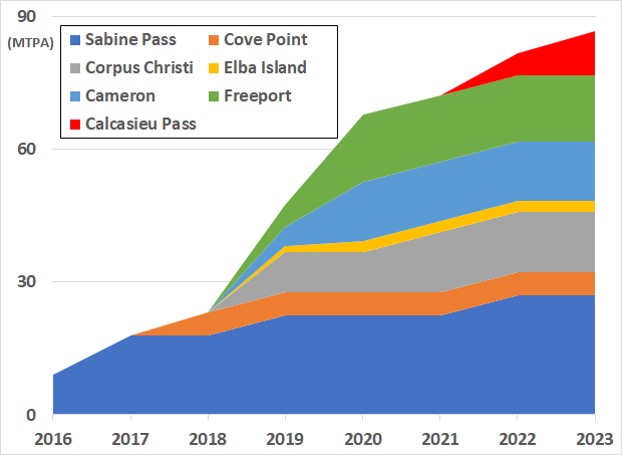

Regarding the current status of LNG export capacity, there are seven LNG export facilities in operation, with a total liquefaction capacity of 86.81 million tons per annum (MTPA) in 2023 (Figure 2). Existing LNG import facilities converted for export include Sabine Pass LNG in Louisiana (which began operation in 2016), Cameron LNG (which began operation in 2019), Freeport LNG in Texas (which began operation in 2019), Cove Point LNG in Maryland (which began operation in 2018), and Elba Island LNG in Georgia (which began operation in 2019). New facilities include Corpus Christi LNG in Texas (which began operation in 2018) and Calcasieu Pass LNG in Louisiana (which began operation in 2022).

Figure 2: Annual liquefaction capacity of LNG export facilities in operation

LNG export facilities are under construction or expansion in five locations to accommodate increased LNG exports. These are Golden Pass LNG in Texas (scheduled to begin operation in 2025-26), Port Arthur LNG (scheduled to begin operation in 2027), Corpus Christi LNG expansion (scheduled to begin operation in 2024), Rio Grande LNG (scheduled to begin operation in 2027-28), and Plaquemines LNG in Louisiana (Phase 1 in 2024 and Phase 2 scheduled to begin operation in 2026). When all are completed, annual liquefaction capacity will double to approximately 160 million tons. Other new projects are also being considered.[9]

A notable trend in the U.S. LNG industry is the entry, as buyers, of not only LNG consuming countries but also LNG exporting countries. State energy companies from Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have agreed to take LNG produced by businesses in Texas.[10] The government of Saudi Arabia, another oil-producing Gulf state, has also announced its participation in an LNG project in Texas with a view to future LNG production projects in its own country.[11] Involvement in the U.S. LNG business brings advantages for Middle Eastern countries: they can keep abreast of cutting-edge efforts to reduce carbon emissions at LNG production facilities and secure new sources of revenue by trading LNG produced in the U.S.

Australia, a major LNG exporter along with the U.S. and Qatar, is also participating in the U.S. LNG business. In July 2024, Australia’s Woodside Energy agreed to acquire Tellurian, which is involved in Driftwood LNG in Louisiana, for approximately $1.2 billion, including liabilities.[12] By utilizing their own tradable U.S. LNG, Australian companies are expected to be able to increase their gas revenues by expanding LNG sales channels to remote export destinations in Europe. This active involvement of the Gulf States and Australia has helped U.S. LNG companies raise funds to cover massive facility construction costs and to secure off-takers for the LNG produced.

Climate Change Measures and the U.S. LNG Industry

Despite the expected growth of the U.S. LNG exports, the impact of climate change measures is also being felt in the U.S. LNG industry. This started when the Biden administration suspended the review process for new LNG export approvals for non-FTA countries in January 2024. As its rationale for the suspension, the Biden administration cited the fact that the current economic and environmental analysis that the DOE uses to determine public interest was conducted approximately five years ago and does not take into account the possibility that subsequent increases in LNG exports have increased energy costs in the U.S. or the latest assessment of the impact of greenhouse gas emissions.[13] In response, the DOE began working on updating its economic and environmental analysis.[14]

In terms of the relationship between climate action and natural gas, the invasion of Ukraine created a trend towards the continued use of natural gas, despite the movement to decarbonize energy usage.[15] Natural gas has a relatively low emissions coefficient for carbon dioxide (CO2), a cause of global warming, compared to coal and oil,[16] and thus serves as a “bridge fuel” during the transition to renewable energy. The Biden administration’s suspension of LNG export approvals, which ran contrary to this trend, has been characterized as a political move in preparation for the upcoming election, in consideration of environmental groups and the left wing of the Democratic Party.[17]

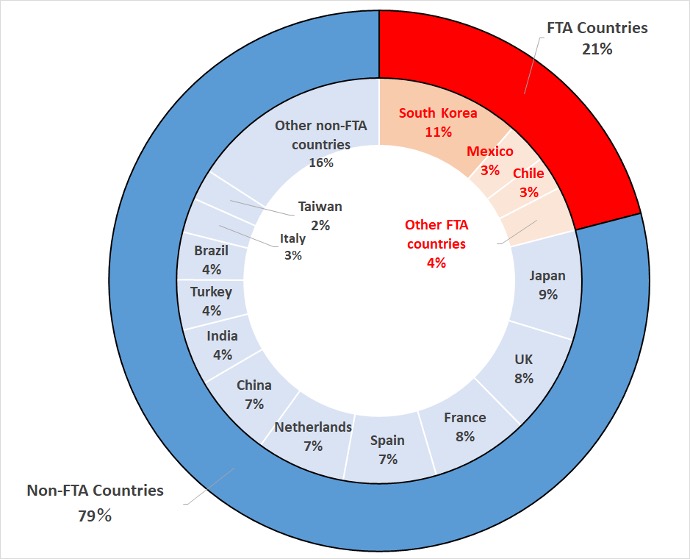

The current round of measures is limited to new LNG exports and those for which approval is pending. The U.S. is expected to maintain its present level of LNG exports for the foreseeable future, as there will be no immediate impact on the LNG exports already approved. However, the evaluation criteria for the economic and environmental analysis are due for an update. If these criteria become more rigorous, a substantial time may be required to examine applications for the extension of approved export periods, not to mention new exports to non-FTA countries. Of all the countries to which the U.S. exported LNG between February 2016 and September 2023, 21% were FTA partners and 79% were not (Figure 3). The construction of new LNG export facilities will be significantly delayed if a substantial number of non-FTA countries review their U.S. LNG procurement plans and refrain from making additional investments or signing new sales contracts. If this occurs, energy supplies from the U.S. to its allies could be adversely affected.

Figure 3: Proportions of U.S. LNG exports to FTA and non-FTA countries

The Biden administration’s measures to freeze LNG exports have been met with increasingly strong opposition from the Republican Party, with its support base in Texas and Louisiana, where LNG export facilities are located. In February this year, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives voted in favor of a bill to override the Biden administration’s export licensing freeze.[18] In July, Judge James D. Cain Jr. of the United States District Court for the Western District of Louisiana, who was appointed by former President Trump, ordered the DOE to lift its suspension of LNG export approvals.[19] In response, the Biden administration appealed the District Court’s ruling, filing a notice of appeal on August 5.[20]

Conclusion: The Potential Impact of the U.S. Presidential Election Result

The conflict between Democrats and Republicans over climate change measures is expected to intensify further as we approach the presidential elections in November. The future of climate change measures and the prospects for LNG exports will differ greatly depending on who wins the U.S. presidential election: Harris, the Democratic candidate with an environmental focus, or Trump, the Republican candidate with an expansionist energy policy stance.

If Trump wins back the presidency, he is expected to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, the international framework to combat climate change, as he did during his first term as President (2017-2021), in an effort to revitalize the oil and natural gas industry. He is also anticipated to immediately roll back the fossil fuel emission regulations introduced by the Democrat administration [21] In addition, he is expected to intervene in the DOE and FERC export approval processes to expand LNG export volumes.

On the other hand, it is anticipated that if Harris becomes president, she will take a more cautious approach to LNG exports and impose a stricter regulatory framework. While it is obviously important to address climate change, overly strict environmental screening may have a negative effect on the development of the U.S. LNG industry and counteract the strengths of U.S.-produced LNG.

(2024/09/09)

Notes

- 1 “EU adopts 14th package of sanctions against Russia for its continued illegal war against Ukraine, strengthening enforcement and anti-circumvention measures,” European Commission, June 24, 2024.

- 2 However, transshipment contracts already signed by June 25, 2024 will not be subject to the application of sanctions until March 26, 2025.

- 3 “DOE's Role in LNG Sector,” U.S. Department of Energy, June 28, 2024.

- 4 Kevin Book, Ben Cahill, Michael Catanzaro, and Kyle Danish, “U.S. LNG Exports: DOE and FERC Roles and Boundaries,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 15, 2024.

- 5 “DOE Issues Two LNG Export Authorizations,” U.S. Department of Energy, March 16, 2024.

- 6 “GIIGNL Annual Report 2024 Edition,” The International Group of Liquefied Natural Gas Importers, June 3, 2024, p.10.

- 7 Kunro Irié, Ben Cahill, Joseph Majkut, and Leslie Palti-Guzman, “Geopolitical Significance of U.S. LNG,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, February 7, 2024.

- 8 In 2023, the Panama Canal Authority temporarily limited the amount of traffic through the canal due to drought conditions that lowered the water level of Lake Gatun, which supplies the water used to operate the canal’s locks. The restrictions on canal traffic will be lifted in stages from August 2024 onward. “Panama Canal traffic to increase as drought conditions ease,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, June 27, 2024.

- 9 The new construction and expansion projects for LNG facilities that have already undergone a Front End Engineering Design (FEED) study include three projects in Louisiana (Cameron LNG expansion, Lake Charles LNG, and Driftwood LNG), three projects in Texas (Freeport LNG expansion, Texas LNG, and Rio Grande LNG expansion), and one project in Mississippi (Gulf LNG). Other plans include the Delfin Floating LNG (FLNG) production facility off the coast of Louisiana in the Gulf of Mexico. The total annual liquefaction capacity of these facilities exceeds 90 million tons.

- 10 “QatarEnergy Trading to offtake and market 70% of LNG produced by Golden Pass,” QatarEnergy, October 22, 2022; “ADNOC Secures Equity Position and LNG Offtake Agreement in NextDecades Rio Grande LNG Project,” Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, May 20, 2024.

- 11 “Aramco and NextDecade announce Heads of Agreement for offtake of LNG from Rio Grande LNG Facility,” Aramco, June 13, 2024; “Aramco and Sempra announce Heads of Agreement for equity and offtake from Port Arthur LNG Phase 2,” Aramco, June 26, 2024.

- 12 Curtis Williams and Ayushman Ojha, “Australia's Woodside Energy to buy US LNG developer Tellurian for $1.2 billion,” Reuters, July 22, 2024.

- 13 “FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Announces Temporary Pause on Pending Approvals of Liquefied Natural Gas Exports,” The White House, January 26, 2024.

- 14 “DOE to Update Public Interest Analysis to Enhance National Security, Achieve Clean Energy Goals and Continue Support for Global Allies,” U.S. Department of Energy, January 26, 2024.

- 15 The 27th Conference of the Parties (COP27) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), held in Egypt in 2022, recognized the use of natural gas as “low emission energy.”

- 16 The relative volume of CO2 emissions (emission factors) emitted to obtain the same amount of heat from combustion is 5 for natural gas (LNG), compared to 10 for coal (common coal) and 7.5 for crude oil. “Examples of Carbon Dioxide Emissions by Fuel,” Ministry of the Environment, accessed August 18, 2024.

- 17 Mike Fulwood, “What next for US LNG Exports?” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, January 2024, p.2.

- 18 Timothy Gardner, “US House passes bill to reverse Biden's LNG pause,” Reuters, February 16, 2024.

- 19 Greg Larose, “Federal court ends pause on LNG export project approvals,” Louisiana Illuminator, July 2, 2024.

- 20 Brad Johnson, “Biden Administration to Appeal Ruling Against Federal LNG Export Application Pause,” The Texan, August 5, 2024.

- 21 In April 2024, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced tighter regulations requiring significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel-powered thermal power plants. “Biden-Harris Administration Finalizes Suite of Standards to Reduce Pollution from Fossil Fuel-Fired Power Plants,” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, April 25, 2024.