Introduction

In shaping the Republic of Korea's (ROK) nuclear policy, the constant factor remains the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK)'s nuclear arsenal, while the primary variable is political transition in both the ROK and the U.S., along with the accompanying shifts in strategic perceptions. With the DPRK's nuclear acquisition now a fait accompli, and concerns that the U.S. government may officially recognize it[1], the policy of complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula is increasingly losing its viability.

From 2023 to 2024, the administrations of the ROK President Yoon Suk-Yeol and the U.S. President Joe Biden collaborated closely to bolster the credibility of U.S. extended deterrence in response to the DPRK's escalating nuclear threat. Their partnership culminated in the establishment of a so-called Korean Nuclear Sharing policy.[2] However, the future of this nuclear policy is still uncertain following Trump’s reelection and the power vacuum created by Yoon's declaration of martial law in December 2024, and its subsequent failure. This paper outlines the nuclear sharing policy pursued by Yoon and its inherent constraints. It also examines how the ROK's nuclear policy may evolve and why discussions of nuclear armament are gaining momentum. The author is well aware that the issue this paper takes up is fairly deep-rooted and with various aspects to explore, such as the impacts of the ROK going nuclear, including the implications to the existing non-proliferation regime under the NPT and possible security dilemmas caused by the ROK’s decision. While the author believes that these aspects should be examined in future studies, this paper aims to initiate an open discussion by introducing the domestic and U.S. situations regarding the ROK's nuclear policy as one of the first steps.

Frames and Limitations of Korean Nuclear Sharing Policy

Over the past two years, ROK's nuclear sharing policy has yielded significant milestones, including the establishment of the ROK-U.S. Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG) and the ROK Strategic Command. In April 2023, Yoon and Biden formalized the NCG through the landmark Washington Declaration.[3] By the third NCG meeting in July 2024, the "U.S.-ROK Guidelines for Nuclear Deterrence and Nuclear Operations on the Korean Peninsula" were unveiled.[4] This framework represents the first joint nuclear operations agreement between the U.S. and a non-nuclear ally, stipulating that the entire process of extended deterrence would be collaboratively discussed, planned, and executed by both nations. Consequently, the integration of U.S. nuclear forces with ROK-U.S. combined conventional forces will be jointly planned under the concept of Conventional-Nuclear Integration (CNI), which formalized from the 2018 U.S. Nuclear Posture Review.[5]

In October 2024, the ROK Strategic Command was inaugurated,[6] tasked with implementing the CNI. This command is designed to deter and respond to DPRK attacks by nuclear and other WMD (Weapons of Mass Destruction) means, integrating and operationally controlling strike assets (ballistic and cruise missiles) previously managed separately by the ROK Army, Navy, and Air Force.[7] However, the essence of the Strategic Command must be understood within the broader context of the nuclear sharing system, the NCG, and the CNI framework that involves both conventional and nuclear strike capabilities possessed by the ROK-US alliance. According to its Presidential Decree,[8] the command's mission includes: 1) planning, preparation, execution, and control of deterrence and response to attacks; 2) cooperation on extended deterrence with the U.S. in the military domain; and 3) integrated operations of strategic capabilities to deter and respond to nuclear and WMD threats.[9] These missions implicitly highlight the shared roles in nuclear usage under the ROK nuclear sharing policy.

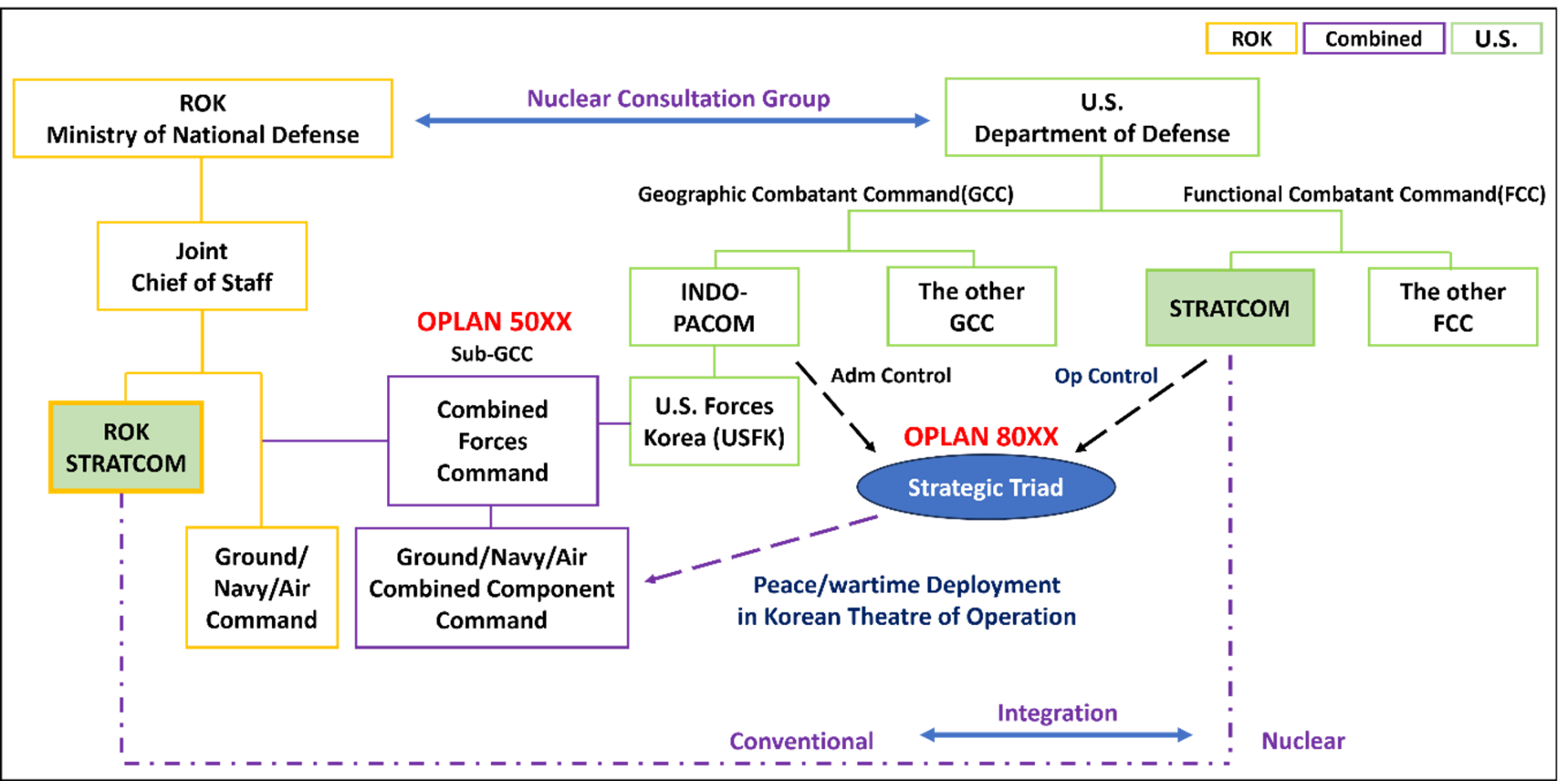

To understand the specific role of the ROK Strategic Command within the framework of nuclear sharing, it is essential to consider the alliance's operational plans. The ROK-U.S. Combined Forces Command (CFC) has developed operation plans, a joint war plan for Korean contingencies that primarily focuses on conventional military operations (e.g., OPCON 5027).[10] In contrast, nuclear operational planning related to extended deterrence now under OPLAN 8010 has traditionally been the exclusive domain of U.S. Strategic Command,[11] with no access granted to ROK forces. However, Under the NCG framework, the ROK Strategic Command has emerged as an official partner to U.S. Strategic Command (see Figure 1). Among the mission objectives of the ROK Strategic Command, the second objective underscores this role in nuclear sharing.

Figure 1:New Structure of U.S.-ROK Alliance

The above nuclear sharing regime aims to enhance the credibility of the U.S. nuclear umbrella by involving the ROK in nuclear planning to a certain extent. However, this approach faces two fundamental limitations. Firstly, the operational control of nuclear weapons would remain outside the purview of the CFC.[12] Consequently, the use of nuclear weapons cannot be integrated into OPLAN 5027, and ROK forces are still excluded from the decision-making stage regarding nuclear weapon deployment. For instance, while the 2024 U.S.-ROK Security Consultative Meeting (SCM) announced that nuclear scenarios would be incorporated into combined exercises starting in 2025,[13] this pertains solely to nuclear defense plans and does not imply ROK forces' participation in extended deterrence.[14]

The second limitation stems from the enduring exclusiveness of nuclear planning dating back to the Cold War's Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP) within U.S. security policy. Despite close cooperation between the ROK and U.S. Strategic Commands, it is unlikely that nuclear planning will allow direct participation by non-nuclear allies. A compromise could involve the ROK's participation in mid-level discussions, where U.S. Indo-Pacific Command and Strategic Command coordinates the deployment of nuclear assets near the Korean Peninsula.[15] For example, a U.S. SSBN recently made a port call in Busan for the first time in 42 years.[16] The ROK's involvement in the regular peacetime rotation of such strategic assets, through its Strategic Command, represents a more subdued form of participation, reflecting the modest and restricted reality of nuclear sharing.[17]

While the nuclear sharing policy is a promising step towards a closer alliance, it falls short of fully addressing the ROK's security concerns. Similar to NATO's nuclear sharing, it does not equate to shared ownership or direct authority over nuclear weapons usage. Even worse, it does not consider nuclear stockpiling in the ROK. Like de Gaulle's analogy of the U.S. nuclear umbrella,[18] the fundamental question remains whether the U.S. would be willing to sacrifice San Francisco for the sake of Seoul.

Beyond Nuclear Sharing to Acquiring?

With dissatisfaction, the future of the Korean nuclear sharing policy itself remains uncertain because of the following reasons. The architects of this policy, both in the ROK and the U.S., have exited the political stage, while a new U.S. administration with a markedly different approach to alliances has taken power. Particularly, the re-emergence of President Trump, who has consistently downplayed the significance of alliances and advocated for the reduction or withdrawal of U.S. forces in the ROK, undermines the very credibility of the alliance. Concurrently, the DPRK is not only amassing warheads but also accelerating the development of delivery systems capable of reaching the U.S. mainland.[19] This situation is reminiscent of the 1957 Sputnik shock, when the Soviet Union's newfound capability to strike the U.S. mainland with a nuclear warhead cast doubt on the reliability of the U.S.'s nuclear umbrella. Consequently, the credibility of U.S. intervention in a Korean contingency is steadily eroding. The existential anxiety stemming from nuclear asymmetry cannot be mitigated by limited nuclear sharing. Given that the ROK no longer faces critical technical barriers to producing nuclear warheads or delivery vehicles, public opinion is increasingly leaning towards nuclearization[20]. The primary obstacles still preventing the ROK from nuclearization are the constraints of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) regime and the pressure exerted by the U.S.

Recent public opinion polls in the ROK reveal a clear perspective on nuclear weapons and the U.S. role in Korea. A June 2024 survey by the Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU) found that nearly 70% of respondents supported the idea of the ROK acquiring nuclear weapons.[21] While the majority still trust the U.S. nuclear umbrella, an intriguing trend has emerged: when given the choice between nuclearization and the stationing of U.S. forces in Korea (USFK), support for the former has surpassed the latter for the first time in history (see Figure 2). The polls also indicate that, regardless of political affiliation, support for the ROK developing its own nuclear capabilities is on the rise. Particularly noteworthy is the significant increase in the proportion of voters who believe that the ROK should pursue nuclearization even in the face of economic sanctions.[22] Candidates aspiring to become ROK’s next leader will closely monitor this public sentiment. Regardless of which political faction ascends to power, it appears increasingly probable that a similar stance on nuclear policy could be adopted.

The shift in the U.S. administration also constitutes a critical variable. President Trump has unequivocally stated that the U.S. will not allow its allies to benefit from its defense capabilities without adequate contribution.[23] This stance has manifested vis-à-vis the ROK through demands for increased defense budget-sharing and threats to reduce the U.S. troop presence.[24] However, the pressure exerted by Trump on the ROK regarding the U.S. troop presence is unlikely to have the same impact as it did for President Carter in 1977 where withdrawal of U.S. Forces in Korea was suggested,[25] due to the reversal in the military capabilities of the ROK and DPRK. In the 1970s, the DPRK military was regarded as superior, while the current ROK forces are far more modernized and better shaped than that of the DPRK.

Figure 2:Opinion Poll, USFK or Nuclear Weapons

Historically, the U.S. military presence served as a formidable deterrent against the DPRK when the DPRK's military power exceeded that of the ROK. Today, however, the ROK boasts superior conventional military strength and industrial capabilities compared to the DPRK.[26] Meanwhile, the DPRK has developed the capability to strike the U.S. mainland with nuclear weapons. In this context, the deterrent role of U.S. forces in the ROK is diminishing. Due to modernization of the ROK military, substantial U.S. assistance in conventional terms in a Korean contingency may not be as essential as it used to be, and the tripwire for U.S. involvement in a crisis has changed from U.S. troops on the peninsula to civilians on the U.S. mainland, thereby undermining the credibility of the nuclear umbrella. The shift in public opinion in the ROK, favoring nuclearization over the stationing of U.S. troops, clearly reflects this reality.

In addition to the U.S. policy of requiring allies to share more defense burdens and the ROK's military buildup, the emergence of China creates another variable to the ROK's nuclear policy. For example, Elbridge Colby, appointed as the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy (USDP) during the second Trump administration,[27] has articulated that the role of U.S. troops in Korea should transition from deterring the DPRK to serving as a tool for containing China. Then, he further asserted that the ROK should assume greater responsibility for its own defense, potentially including nuclearization.[28]

His mention about the ROK’s nuclearization contradicts traditional U.S. foreign and security policy. However, comparing the ROK's position to that of NATO suggests its logic. First, unlike NATO, the ROK has superior conventional forces relative to its main threat (the DPRK for the ROK and Russia for NATO). Second, the ROK faces a direct nuclear menace, unlike NATO. Third, while NATO and the U.S. share the primary threat, the ROK's primary threat is the DPRK, whereas for the U.S., it is China. With the U.S. focusing on China, it is contradictory to ask the ROK to enhance its military capabilities without additional nuclear-related trade-offs (such as nuclear sharing beyond NATO, developing nuclear propulsion submarines, or allowing plutonium reprocessing). That would be the reason why Colby mentioned the nuclearization of the ROK, even if the possibility remains low. The ROK government and military also well recognize the challenges of nuclearization, however, the current security situation could shift domestic public opinion in favor of nuclear acquisition.

Conclusion

The constants and variables set in the introduction, influencing the ROK’s nuclear policy are increasingly steering Seoul towards nuclearization rather than limited nuclear sharing. It will be a major factor that policymakers of both the ROK and the U.S. will weigh. Indeed, the concepts of nuclear sharing and nuclearization span a broad spectrum that this analysis has not fully explored. For instance, nuclear latency, depending on its degree, could have a strategic impact just less than nuclearization.[29] What is crucial is that, regardless of where the ROK chooses to position itself on this spectrum, it must make decisions that maximize the strategic interests of both allies, while avoiding isolation in the NPT regime. Both parts require further study. Public opinion is crucial, but not always driven by rational and realistic calculations of national interest, nor can it predict the outcomes of diplomatic negotiations. In the long term, it would be essential for the ROK to pursue policies that yield the best outcomes for national security, considering a wide variety of dimensions including those stated above.

(2025/02/18)

Notes

- 1 “Trump reference to N.Korea as nuclear power worries S.Korea“, NHK WORLD, Jan 21, 2025.; “Pentagon chief nominee depicts N. Korea as 'nuclear power,' calls for allies' increased 'burden sharing'“, The Korea Times, Jan 15, 2025.

- 2 “What the new S. Korea-US Nuclear Consultative Group will look like“, HANKYOREH, April 27,2023.; “Hwakjangokje guchejok jakdong, hanmi hannguksik haekgonyyu sokdonenda“ (Speeding Korean Nuclear Sharing, detailed operation of extended deterrence), Seoul Economics, April 20, 2023.

- 3 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Korea, Washington Declaration, April 28, 2023.

- 4 U.S. Embassy & Consulate in the Republic of Korea, Joint Statement by President Joseph R. Biden of the United States of America and President Yoon Suk Yeol of the Republic of Korea on U.S.-ROK Guidelines for Nuclear Deterrence and Nuclear Operations on the Korean Peninsula, July 12, 2024.

- 5 U.S. Office of the Secretary of Defense, Nuclear Posture Review 2018, February 2018. p.14.

- 6 “S. Korea launches strategic command to counter N. Korean nuclear threats”, The Chosun Daily, October 1, 2024.

- 7 “Kukbangbu, jeonryaksaryongbuga F-35, jamsuham, uju, jonjagibudae tongje.” (Ministry of National Defense, Strategic Command Takes Control of F-35, Submarines, Space, and Electronic Forces), Yonhap News, February 2, 2023.

- 8 ROK Presidential Decree of ROK STRATCOM.

- 9 Ibid, Article 2.

- 10 As Examples, see Thomas E. Ricks, “Why ‘5027’ is a number you should know: How war in Korea might unfold”, Foreign Policy, May 1, 2017.

- 11 As Examples, see Hans Kristensen, “US Nuclear War Plan Updated Amidst Nuclear Policy Review”, Federation of American Scientists, April 4, 2013.

- 12 U.S. Joint Chief of Staff, Joint Publication 3-72 Nuclear Operations, 11 June 2019, p.30.

- 13 “Hanmi, jakkee bukui haekgonggyeok sinario banyounghakiro” (U.S.-ROK to incorporate North Korean nuclear attack scenarios into operational plans), Chosunilbo, October 31, 2024.

- 14 “Hanmi SCM gongdongsonmyong, bihaekhwa jiugo haekgaebal jiyeon noryok nootta.” (U.S.-ROK SCM joint statement removes 'denuclearization' and inserts 'efforts to delay nuclear development'), Hankookilbo, October 31, 2024.

- 15 U.S. Joint Chief of Staff, supra note 9., Chapter IV.

- 16 “USS Kentucky Make Port Call in South Korea, First SSBN Visit in 40 Years”, U.S. Naval Institute News, July 18, 2023.

- 17 U.S. Joint Chief of Staff, supra note 9., p.20.

- 18 U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume XIV, Berlin Crisis, 1961–1962, 30. Memorandum of Conversation, May 31. 1961.

- 19 “North Korea says new hypersonic missile will 'contain' rivals”, BBC, Jan 7, 2025.

- 20 Korean Institute of National Unification, KINU Unification Survey 2024 Executive Summary EN, June 27, 2024.

- 21 Ibid., p.60.

- 22 Ibid., p.65.

- 23 Victor Cha, “How Trump Sees Allies and Partners“, Center for Strategic & International Studies, Nov 18, 2024.

- 24 “Trump suggests $10 billion price tag for US troops in South Korea“, Radio Free Asia, Oct 16, 2024.

- 25 “Carter's Decision on Korea Traced Back to January 1975“, Washington Post, June 11, 1977.

- 26 As Examples, see “2025 Military Strength Ranking“, Global Fire Power.

- 27 “Trump announces picks for deputy secretary of defense, other top DOD posts”, defensescoop, DEC 22, 2024.

- 28 “(Yonhap Interview) Ex-Pentagon official stresses need for war plan rethink, swift OPCON transfer, USFK overhaul“, Yonhap News Agency, May 8, 2024.

- 29 Tristan Volpe, “Playing with Proliferation: How South Korea and Saudi Arabia Leverage the Prospect of Going Nuclear“, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 19, 2024.