In April 2023, military conflict broke out between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the RSF, a paramilitary force. After 15 months, there is no end in sight and Sudan faces its most serious humanitarian crisis in 40 years. However, the international community has shown little interest in Sudan, neglecting the crisis. What is currently happening in Sudan, and is there a way to resolve it? This report will touch on the current state of military conflict and humanitarian conditions in Sudan, as well as obstacles to conflict resolution, and consider future steps.

Military clash to present

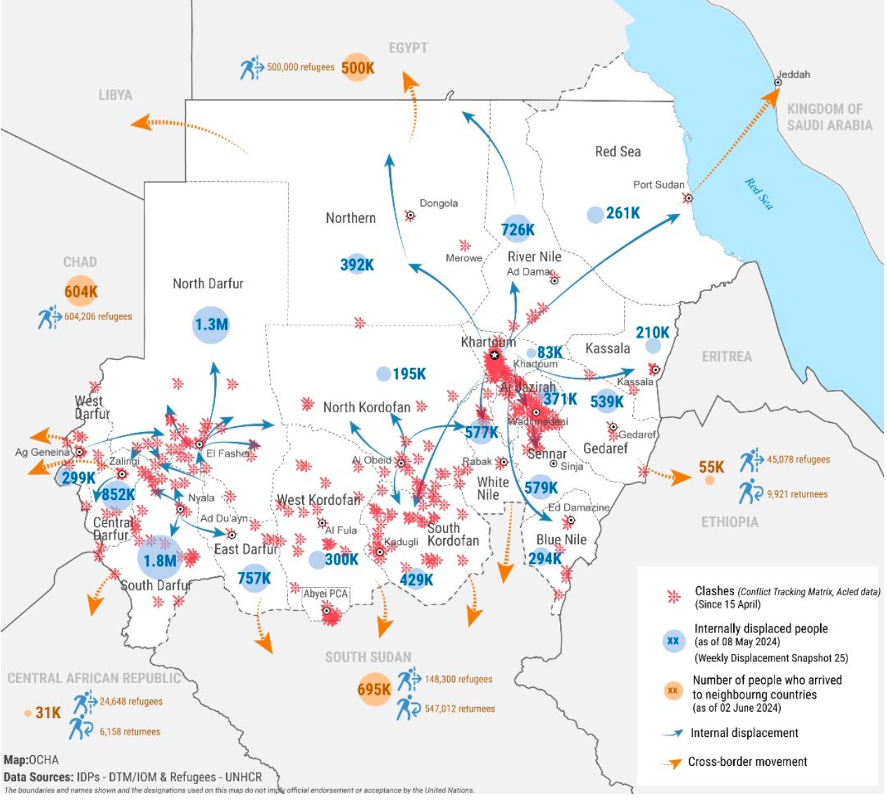

The military clash between the SAF and RSF in April 2023 was triggered by the issue of integration between the two parties, both of which belong to government military organizations. Because the SAF was expected to have an overwhelming advantage in terms of the quantity and quality of soldiers and weapons, it was expected that the fighting would end within a few weeks, or at most two to three months, with the SAF in the superior position. However, contrary to expectations, the RSF proved to be capable fighters, and in August 2023, SAF Supreme Commander Abdel Fattah al-Burhan moved his base from the capital of Khartoum to Port Sudan on the Red Sea coast. In December 2023, the RSF invaded Wad Medani in the state of Gezira, south of Khartoum. From around February 2024, the SAF regained its footing, and its area of control expanded in Khartoum as well. Meanwhile, since April 2024, the RSF has been conducting intensive attacks on El Fasher in the state of North Darfur in western Sudan, where the SAF has a military base[1] and, since late June, has also been fighting in the states of Sennar[2] and West Kordofan[3] in southern Sudan (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Combat zones and humanitarian situation in Sudan

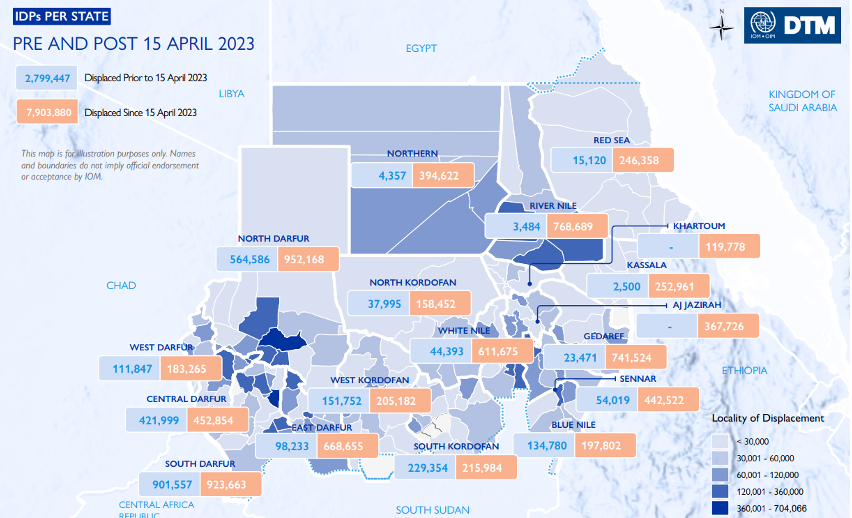

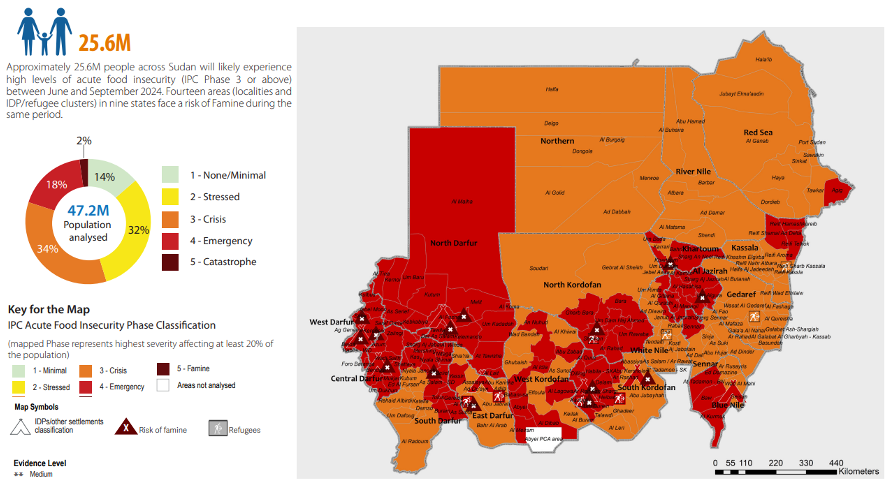

According to the United Nations, 150,000 people are estimated to have died as a result of the fighting[4], but the humanitarian crisis continues. As of July 23, 2024, approximately 10.7 million people are internally displaced (of which 7.9 million are internally displaced since the military conflict in April 2024), and approximately 2.27 million people have fled the country (see Figure 2). This is the largest number of displaced people in the world. In addition, approximately 25.6 million people, more than half of the population, are in a state of "Phase 3 (acute food insecurity level)" or higher in the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), an indicator of food security (see Figure 3). Clingendael, a Dutch institute of international relations, estimates that in the worst-case scenario, approximately 2.5 million people will starve to death by September 2024[5]. This is the most serious humanitarian crisis since the Ethiopian famine in the 1980s[6]. However, Western media has focused on Gaza, Ukraine, and national elections in various countries, and Sudan has been left in a state of neglected.

Figure 2: Internally displaced persons in Sudan (as of July 23, 2024)

Figure 3: Food crisis in Sudan

Factors contributing to the continued military clash

Since the military clash in April 2023, neighboring countries and major powers have made some efforts to resolve the conflict. Various countries, including the United States, have continued to work toward mediation.

However, factors outweighing these efforts result in the continuation of the military clash. Looking at the situation in Sudan, the main cause is the deep feud between Burhan, head of the SAF, and Hemedti, head of the RSF. The military clash on April 15, 2023, began in the early hours when the RSF raided Burhan's official residence. At least 35 of Burhan's guards were killed, and Burhan only barely escaped[7]. This is thought to have triggered Burhan's hatred for the RSF. On the other hand, Hemedti is likely aware that this attack and numerous killings and abuses place him in a position intolerable to the SAF and the general citizens. In other words, the April 2023 clash crossed a red line.

In addition, Islamists, who have been increasing their presence since the clash, are an obstacle to a ceasefire and reconciliation[8]. The Islamists held strong influence until the collapse of the Bashir regime in 2019. Their political entity then, the National Congress Party (NCP), was dissolved and banned from taking part in politics under the democratic transitional government that had been established since April 2019. However, since the military clash in 2023, Burhan, who has been at a disadvantage, has sought cooperation from the Islamist group, paving the way for the Islamists to return to the political stage. The Islamists have demanded that Burhan not agree to reconciliation or a ceasefire with the RSF, and Burhan himself has been forced into a situation where he cannot refuse the Islamists' demands.

Domestic factors are not the only reason why the military conflict in Sudan cannot be resolved. The involvement of other countries in Sudan is also an obstacle. Sudan is located at the junction of Arab and Black Africa, and faces the Red Sea, a strategic hub for maritime trade. In addition to gold, Sudan also has fertile soil that enables the export of agricultural products and livestock to neighboring countries. Because Sudan is in such an important geopolitical position, various countries have tried to build relationships with different forces within Sudan. As a result of financial and military support provided by foreign countries to both the SAF and the RSF[9],15 months have passed, but the military clashes continue with no shortages of weapons or ammunition.

Further risks

As the military clash continues, new concerns have emerged. Three points stand out.

First, the rise of the Islamists will impact the behavior of other countries. As mentioned above, the Islamists’ influence has been expanding since the outbreak of the conflict. Sudanese Islamists have close ties with the Muslim Brotherhood, and the expansion of Islamist influence means the reinvigoration of the Muslim Brotherhood. In the past, countries such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have repressed the Muslim Brotherhood, while Turkey, Qatar, and Iran have been more tolerant. The UAE is said to be supporting the RSF militarily, not only because of gold, which is mainly controlled by the RSF, but also because of caution toward the Islamists, who are expanding their influence under the SAF[10]. The rise of the Islamists may impact the behavior of neighboring countries in Sudan. Egypt, in particular, strongly backs the SAF, but is very wary of the expansion of the Muslim Brotherhood's power. In addition, the influx of 510,000 refugees from Sudan[11] and refugees from Palestine are destabilizing factors in Egypt, so it will be important to see what stance Egypt takes in its intervention in the clash in Sudan.

Second, the expansion of Islamist influence has been accompanied by the influx of various Islamic extremist groups, including IS, into Sudan[12]. There is concern that Sudan may become a hub for jihadists in the near future.

Third, Russia and Iran have recently become actively involved. Russia has had close ties with the RSF through the gold trade, but in light of the SAF's relocation to Port Sudan and the change in the war situation, Russia is strengthening its approach toward the SAF with the aim of securing a base on the Red Sea[13]. Iran has provided the SAF with weapons in response to the SAF's request for cooperation, and is also rapidly strengthening diplomatic relations[14]. Russia and Iran's active involvement in Sudan's internal affairs could further complicate the ceasefire, peace, and reconstruction process.

Path to resolving the humanitarian crisis

After 15 months, Sudan's military clash has become more complicated and the prospects for a resolution seem to have diminished. Nevertheless, the international community should work together to support Sudan, which is facing its most serious humanitarian crisis in 40 years, in improving the situation.

First, it is necessary to minimize famine by realizing a ceasefire and humanitarian assistance. As mentioned above, there are factors that make both the SAF and the RSF reluctant to accept a ceasefire, and the domestic and international stakeholders surrounding them also make this difficult. In order to restrain the military actions of the SAF and the RSF, who are the main actors in the current clash, monitoring should be strengthened to ensure that the arms embargo, which is not currently being observed, is strictly enforced. Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, which have influence in Sudan, should work to bring both the SAF and the RSF to the negotiation table. It is important for Western countries, including Japan, to work more to encourage Sudan’s neighbors to actively move toward a ceasefire.

Regarding the implementation of humanitarian aid, aid provided by the United Nations, NGOs, etc. is hindered by the denial of travel permission, and by being subject to looting and attacks[15]. Alex de Waal of Tufts University points out that hunger is being used as a "tool of war" to put the opposing side at disadvantage[16]. Besides, only 31.5% of UN humanitarian appeals have been met until now[17].

During the Ethiopian famine in the 1980s, a widespread hunger relief campaign was conducted through Live Aid, which was organized by musician Bob Geldof and then Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, urged the Ethiopian government to support food aid from the United States[18]. This made international support for famine relief in Ethiopia possible. The international community is showing little interest in Sudan now, and there is no international momentum for the international community to come together to provide famine relief, as was the case with the United States and the Soviet Union at the time of the Ethiopian famine. It is necessary to raise awareness on Sudan in the international community to push both the SAF and the RSF to enable humanitarian access and to further increase humanitarian assistance. The main stakeholders in Sudan today are Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. Major countries and the UN, which seek to resolve the humanitarian crisis, need to involve Gulf countries such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which play important roles in the region, and create an international framework to materialize a ceasefire and humanitarian assistance.

Following the ceasefire, full-scale development assistance for reconstruction in Sudan will once again be needed. Major infrastructure has been destroyed in the fighting, and public services such as water, health, and education have also suffered devastating damage. Full-scale support from the international community will be necessary for recovery and reconstruction, but this support likely will not materialize without the resumption of the democratization process. From the collapse of the Bashir regime in 2019 to the political turnover in October 2021, the democratization process progressed, and a great deal of support was provided to Sudan, which had been isolated from the international community for 30 years. At that time, a path to resolving Sudan’s enormous accumulated debt of US$ 60 billion was under consideration[19]. Unless the democratization process gets back on track, such full-scale support is unlikely to appear.

Currently, Sudan's democratization has greatly receded. Taking advantage of the fighting between the SAF and the RSF, former armed groups from Darfur have intervened in eastern Sudan, and local armed groups based on tribes have emerged in various locations[20]. Meanwhile, many members of the FFC, a pro-democracy political coalition, have fled overseas, and some members, including former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdouk, have formed a coalition called Taqaddum. However, they have not yet gained substantive power[21]. At the civilian level, the Resistance Committee has been the core of the democratization movement, but some have become displaced during the fighting, and those who remain have been detained or repressed by the SAF and the RSF, weakening them[22].The seeds of democratization are in danger of being eradicated.

Both the October 2021 political turnover and the April 2023 military clash occurred at a time when major military groups, such as the SAF and the RSF, were in existential crisis. The 2021 turnover occurred just before the head of the Sovereign Council, the state's highest decision-making body, was to transfer from the military to the democratic faction under the democratic transition process. The 2023 military clash occurred amid ongoing discussions on the unification of the SAF and the RSF. In other words, the political turnover in October 2021 and the military clash in April 2023 were the result of armed groups, such as the military and armed forces, resisting the threat of weakening their own organizations. Joshua Craze of the Open Society Foundations argues that "conflict is a system that generates profits for armed groups, and the structure of rule by force is the cause of conflict. To resolve this, it is necessary to review the international market system of resources such as gold and diamonds[23]."

As mentioned above, Sudan faces the Red Sea and is located at the intersection of Arab and Black Africa, which is a geopolitically important location that attracts the interest of foreign countries. This is the reason why Sudan has been exposed to conflict so far. In addition, before South Sudan's independence from Sudan in 2011, oil attracted the interest of other countries. Since South Sudan's independence, gold has similarly drawn other countries’ interest. A highly transparent monitoring system for such resources is necessary to suppress conflict.

Ending the military clash in Sudan and getting the democratization process back on track will not be easy. However, the international community must not ignore the current humanitarian crisis, nor allow Sudan to become a hub for jihadists. What is needed is greater awareness of Sudan in the international community, the involvement of all relevant countries that have interests in Sudan, and the construction of a consensus to restart the democratization process.

*This article was written based on information available as of July 28, 2024. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the organization to which the author belongs.

(2024/08/09)

Notes

- 1 Ilhan Dahir, “As famine spreads across Sudan, protecting civilians must be a priority,” United States Institute of Peace (USIP), July 18, 2024.

- 2 Sudan War Monitor, “Battle begins for eastern Sudanese city,” July 12, 2024.

- 3 Sudan War Monitor, “West Kordofan violence forces thousands to South Sudan,” July 23, 2024.

- 4 Ilhan Dahir, op.cit.

- 5 Clingendael, “From hunger to death,” May 2024, p.4.

- 6 Rebecca Paveley, “World’s worst famine in 40years: why is Sudan ignored, Archibishop Welby asks,” Church Times, June 17, 2024.

- 7 Alden Young, “How Sudan’s wars of succession shape the current conflict,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, July 3, 2024, p.13.

- 8 “Sudan army chief under pressure from Islamist backers: analysts,” France 24, May 29, 2023.

- 9 Amnesty International, “New weapon fuelling the Sudan conflict,” July 25, 2024.

- 10 Aidan Lewis, “Sudan’s conflict: Who is backing the rival commanders?” Reuters, April 12, 2024.

- 11 IOM, “DTM Sudan Mobility Update (04),” July 23, 2024.

- 12 Herbert Maack, “One year on, civil war risks reviving Jihadist in Sudan,” The Jamestown Foundation, Terrorism Monitor, July 9, 2024.

- 13 Andrew McGregor, “Rusia switches sides in Sudan war,” The Jamestown Foundation, Eurasia Daily Monitor, Volume 21, Issue 102, July 8, 2024.

- 14 “Why Sudan’s army is pivoting toward Iran,” The New Arab, February 12, 2024; Sudan Tribune, “Al-Burhan accepts credentials of new Iran ambassador to Sudan,” July 21, 2024.

- 15 Daclan Walsh, “As starvation spreads in Sudan, military blocks aid trucks at border,” The New York Times, July 26, 2024.

- 16 Alex de Waal, “Sudan’s manmade famine,” Foreign Affairs, June 17, 2024.

- 17 UN OCHA, “Sudan Humanitarian Response Plan 2024,” observed July 28, 2024.

- 18 Alex de Waal, op.cit.

- 19 Koji Sakane, “One year after Sudan’s political turmoil: democracy and development are urgently needed,” Sasakawa Peace Foundation International Network Analysis (IINA), December 21, 2022.

- 20 YCON Sudan, “Special Report: The implications of war and multiple armies in Eastern Sudan,” July 2, 2024, p.19.

- 21 Dame Rosalind Marsden, “A strong civilian coalition is vital to avert Sudan’s disintegration,” Chatham House, June 21, 2024.

- 22 YCOM Sudan, op.cit., pp.49-50.

- 23 Joshua Craze, “Rule by militia,” Boston Review, June 26, 2024.