In Sudan, political turmoil erupted on October 25, 2021, when the military detained democratically elected Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdouk. Abdel al-Burhan, commander-in-chief of the armed forces and chairman of the Sovereign Council, declared a state of emergency and announced the dissolution of the Sovereign Council and Cabinet. Hamdouk was released from house arrest in mid-November and reinstated as prime minister, but resigned in January 2022 after he failed to win the public support from pro-democracy factions. Since then, the military has remained in power, and the African Union (AU) has suspended Sudan’s membership as the de-facto political regime does not represent the country.

Historically, Sudan has experienced numerous coups since its independence from colonial rule in 1956. The country has been democratizing since the Sudanese Revolution in April 2019 ousted then-President Omar al-Bashir, who reigned for 30 years.

One year after the turmoil of October 2021, one is left to question whether the democratic process will dissipate in Sudan, or whether it be revived? This piece will examine the socio-economic impact and challenges that came with the political turmoil in 2021.

A year after turmoil: political and economic crisis, tribal conflicts

October 25, 2022, marked one year since the turmoil of 2021. Mass demonstrations broke out across the country against the military-led regime. Although the internet was cut off in the daytime, it was restored in the evening. The next day, city traffic and people’s movements returned to normal, as if nothing happened the day before. The world’s attention was focused on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the Tigray conflict in Ethiopia, and little attention has been paid to Sudan. However, social conditions in Sudan have worsened over the past year.

Since the unrest last year, many clashes have taken place and negotiations have occurred between the military and democratic forces, but the military-led system has remained in place. Demonstrations have been held at least once a week, but the "Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC)," a coalition of pro-democratic parties, lacks a consolidated leadership and remains divided[1]. “Resistance Committees,” community-based associations of citizens, organize demonstrations on a monthly basis, and some committees have released plans for political consolidation, but no major changes have materialized.

The international community had supported Sudan’s economic stability by initiating discussions in January 2021 on cancelling Sudan’s $60 billion debt, reaching the ‘Decision Point’ in July 2021, when major lending stakeholders, such as advanced economies, the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other lending organizations, confirmed the start of cancellation process. After that, both Sudan and lenders worked to cancel the debt, and if the process had concluded successfully, a significant amount of debt was expected to be cleared. However, after the turmoil in 2021, the international community, led by Western countries, did not recognize the military-led regime that expelled pro-democratic groups by force, and consequently the debt relief process was suspended. Similarly, Western countries suspended the formulation of new bilateral development projects with Sudan, except direct humanitarian assistance to victims of disasters and conflicts, and development assistance to civil society.

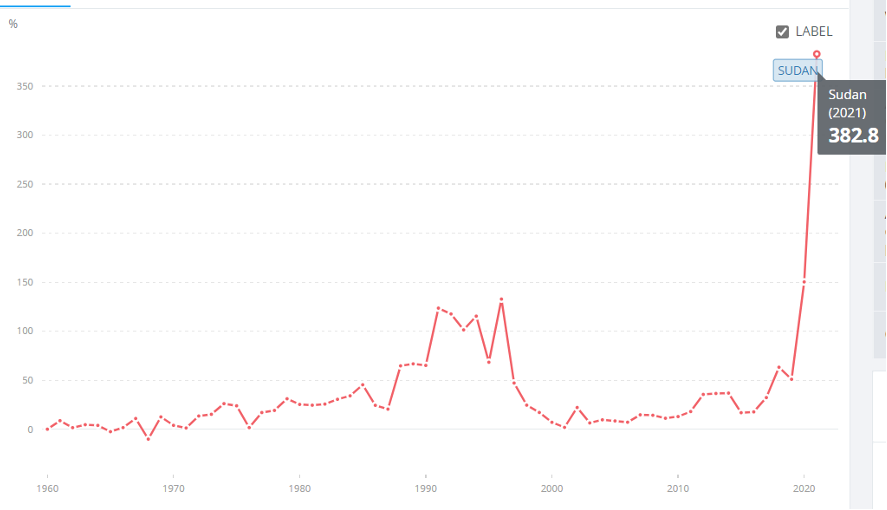

The economy has stagnated, with inflation exceeding 380% year-on-year in 2021 (Figure 1). It is a serious figure, as few countries have experienced triple-digit inflation. Moreover, the economic growth rate in 2022 is projected to be minus 0.3%[2], and gross domestic product (GDP) per capita has plummeted by more than half from US$1,679 in 2015 to US$772 in 2021 over the past six years[3].

(Figure 1) Inflation Rate (year-on-year) [Source: IMF, 2022]

Government finances are deteriorating rapidly due to the suspension of foreign aid and the deterioration of the economy. The budgets allocated to ministries and state governments are drying up, and the quality of public services, such as infrastructure and water provision, has worsened. Strikes by civil servants demanding wage increases and improved working conditions occur frequently. In addition to soaring prices for daily necessities, the prices of public services like electricity, road tolls and user fees for irrigation facilities have also been raised[4]. Shop owners close local markets all at once, and farmers petition against rising irrigation user fees. In November 2022, due to global food crisis and torrential rains and floods between August and September, the United Nations announced that 15.8 million people, 30% of the population, need humanitarian assistance[5].

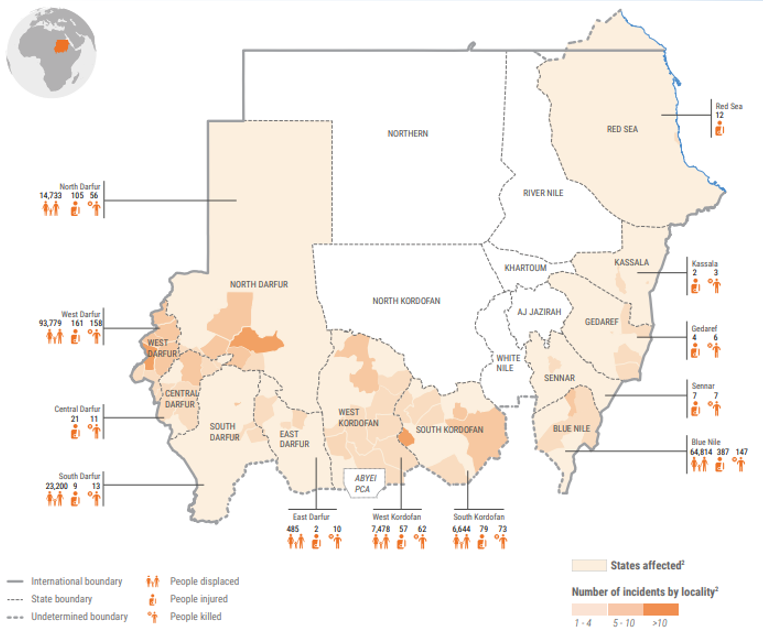

Tribal conflicts are rapidly proliferating in Darfur, which borders Chad, as well as in the southern regions of Blue Nile State and West Kordofan State (Figure 2). In Blue Nile State, conflicts between the Hausa and the local ethnic group have escalated, although the Hausa of Nigerian descent have coexisted peacefully over the past few decades. At least 359 people have died in the state since July 2022[6]. As locals in Blue Nile State condemned the state government for its slow response to the deteriorating security, the state building was set ablaze by a crowd of protesters. To quell the situation, the governor imposed a curfew. In West Kordofan State, the conflict between nomadic and agrarian tribes has intensified, and residents have demanded the establishment of a new state, ‘Central Kordofan’[7].

More than 210,000 people have been displaced due to these communal clashes as of September 2022[8]. In these cases, the deterioration of the socio-economic situation has made people's lives more difficult, amplifying aggression, hatred and exclusionary behavior toward different ethnic groups, thus resulting in widening divisions among tribes.

(Figure 2) Community Conflict in Sudan (January-September 2022) [Source: UN Office for Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), October 11, 2022]

Future concerns: population growth and desertification

The impact of Sudan’s socio-economic deterioration is not limited to the present. There are growing concerns about future threats.

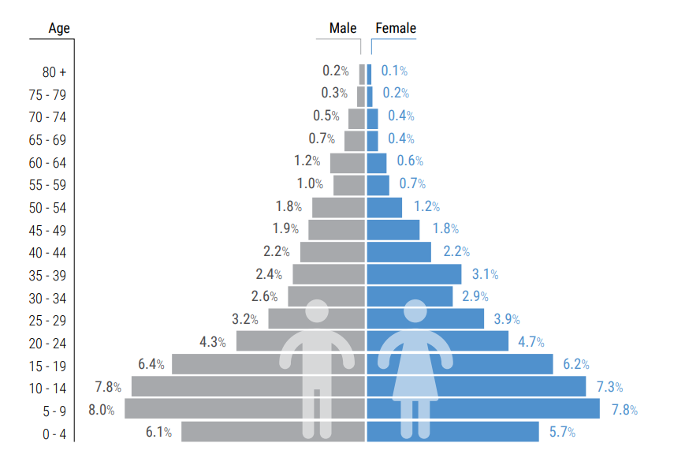

The first is population growth and unemployment. Sudan has a high birth rate, with 55% of the population under the age of 20 (Figure 3). The population is expected to increase from about 49 million today to 81 million by 2050[9]. In Sudan, it is not uncommon to have 4 to 5 children per family. About 80% of the population is engaged in the agricultural sector[10], but since farmers cannot distribute their land to all their children, some children must find jobs in other sectors. With the unemployment rate already at the critical level of 30.6% in 2022[11], it is essential to create job opportunities to absorb the increasing working population.

(Figure 3) Demographic composition of Sudan [Source: Sudan Humanitarian Needs Overview 2023 (UN)]

There are also concerns about the health and growth of children, who will in turn bear the next generation. Due to the current food crisis, 11.7 million people, or one quarter of the population, are at or above the IPC (Acute Food Insecurity) Phase 3 "crisis level" (8.6 million people for IPC Phase 3 “Crisis level" and 3.1 million for IPC Phase 4 "Emergency level")[12]. 4 million people in Sudan suffer from malnutrition as health services deteriorate[13]. Malnutrition in infants could cause significant damage to their normal growth. In the education sector, 6.9 million people, or one-third of school-age children, cannot go to school. According to a sample survey by the non-government organization ‘Save the Children,’ 80% of children in the third grade of elementary school cannot read simple sentences, and 70% cannot read a single word[14]. Children who suffered from stunting and a lack of childhood education will reach adulthood in the next 20 years. This is cause for serious concern regarding the formation of a sound and healthy society. Unless this situation is improved, this fragile social structure will continue and intensify in the future.

An even bigger concern is the medium- to long-term effects of desertification. 72% of land in Sudan is categorized as arid or semi-arid areas, but according to a survey by the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), between 250,000 and 1.25 million hectares of forest have disappeared in the 10 years since 2005[15]. Since the 1930s, the Sahara Desert has moved southward by 50 to 200 kilometers, and it is predicted that it will continue to move south at a speed of about 1.5 km per year[16]. (Note: Most conflicts in Sudan occur between agrarian and nomadic tribes on the edge of desertification[17].) Although 80% of the population depends on the agricultural sector[18], there is a risk that the whole of Sudan will be swallowed up by this wave of desertification, rendering agriculture unsustainable except along the Nile River basin.

A path forward: resumption of democratic process and promotion of development

As of 2016, about 4.5 million Sudanese people live abroad[19]. The desire among Sudanese to move abroad is rising with the recent deteriorating political and economic situation, and the number of people who are forced to abandon their homeland may rise in the future.

Political negotiations have taken place between the military and the main FFC groups in Sudan since the turmoil of last year, and on December 5, the “Framework Agreement” was signed among major groups[20]. While United Nations and many foreign countries welcomed this agreement, many observers doubted its credibility[21] and many citizens protested against it.

The future of Sudan is for the people of Sudan, not external actors, to decide. However, with conditions as they are it is difficult to expect the country to receive full-fledged support from the international community. Considering the current humanitarian crisis, concerns about population growth and employment in near future, and further risks of desertification in the longer-term, action is urgently needed.

It is first necessary to break out of the current political stalemate, resume the democratic process, and rebuild a political system that the international community recognizes as ‘legitimate.’ It is also necessary to guarantee basic human needs, such as the provision of food, water, electricity and medical services; to improve the quality of life through better education and infrastructure; and to form a reliable judicial and police system that provides the people with peace of mind. It is also necessary to support agricultural development, the creation of industry, promote employment, and put the government’s finances back on track. A resilient administrative system that can operate public services and human resource development for civil servants are also needed.

This is not the time for quarreling or fighting among the Sudanese people. It is the time to work together to avoid the division and collapse of the nation and create a society where all Sudanese and their children can live peacefully in their own country. All stakeholders involved in political negotiations need to waive their self-interests and quickly form a consensus that the Sudanese people will accept in order to assure the development and prosperity of current and future generations.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and are not the official views of the author's organization.

(2022/12/21)

Notes

- 1 Mohammed Amin, “Sudan’s opposition divided with political deal on transition imminent,” Middle East Eye, 19 September 2022.

- 2 Shoshana Kedem, “US balks at sanctions on Sudan’s military,” African Business, 3 November 2022.

- 3 Data from the International Monetary Fund, "World Economic Outlook Database (October 2022)."

- 4 Farouck Kamabreesi, “To save its economy, Sudan needs civilian rule,” Aljazeera, 25 October 2022.

“Report: Dismal performance of Sudan economy will continue if military rule persists,” Debanga, 18 October 2022. - 5 UN OCHA, “Sudan Humanitarian Needs Overview 2023,” November 2022, p.6.

- 6 United Nations, “Resurgence of ethnic clashes in Sudan’s Blue Nile region triggers death and destruction,” 3 November 2022.

Marc Espanol, “New Wave of Violence in Sudan puts Coup Generals in Spotlight,” Al-Monitor, 6 November 2022. - 7 “Sudan’s Hamar demand new state of Central Kordofan,” Debanga, 4 October 2022.

- 8 UN OCHA, “Inter-communal Conflicts and Armed Attacks (January –September 2022),” 11 October 2022.

- 9 See footnote 5, p.16.

- 10 “Climate, Peace and Security Fact Sheet; Sudan,” Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) and Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (Sipri), May 2022.

- 11 Data from the International Monetary Fund, "World Economic Outlook Database (October 2022)"

- 12 See footnote 5, p.55.

IPC is an indicator of the state of food security, the “Integrated Food Security Phase Classification.” The grade is decided by the IPC Steering Committee, which is consisted of 15 organizations, including the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Food Programme (WFP), and an international NGO, Care International. The IPC's Acute Food Insecurity is based on the impact of the food crisis on people's lives and livelihoods: Phase 1 “None/Minimal,” Phase 2 “Stressed,” Phase 3 “Crisis,” Phase 4 "Emergency," and Phase 5 "Catastrophe/Famine."

IPC_Brochure_Understanding_the_IPC_Scales.pdf - 13 See footnote 5, p.62.

- 14 See footnote 5, p.52.

- 15 Sarra A.M. Saad et al, “Combating Desertification in Sudan: Experiences and Lessons Learned,” Conference Paper for “Public private partnerships for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” UN, April 2018.

- 16 “Climate Change Risk Profile: Sudan,” USAID, 31 August 31 2016.

- 17 See footnote 10.

- 18 See footnote 10.

- 19 “Migration Profile: Sudan,” Migrant and Refugees Section, Vatican City, January 2021.

- 20 Khalid Abdelaziz and Nafisa Eltahir, “Sudan generals and parties sign outline deal, protesters cry foul,” Reuters, December 5, 2022

- 21 Amgad Fareid Eltayeb, “Is it true that the framework agreement guarantees the striping military from power, or vice versa?” Sudan Tribune, observed December 13, 2022.