On April 15, 2023, military clashes broke out between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary, Rapid Support Force (RSF)[1] in Sudan. Even after three months, the fighting has not ended. On the contrary, the capital, Khartoum, has suffered devastating damage, and the fighting has spread, causing more than 3 million people to be displaced across the country and abroad[2]. This is the first time that large-scale fighting has taken place in Sudan’s capital[3], although there have been numerous armed clashes since its independence in 1956. Unless the current armed clashes are stopped as soon as possible, Sudan will be irreparably damaged and the political situation in the surrounding region will become destabilized.

This paper will analyze the current situation in Sudan and its impact, referring to the causes that led to the armed clashes, their development, and the response of the international community.

Why did the armed clashes occur?

The armed clashes began suddenly on the morning of April 15. However, in the political context of Sudan, it was a conflict that was bound to happen.

In April 2019, the democratic revolution in Sudan led to the collapse of the 30-year-long Bashir regime and the formation of a transitional democratic government. In October 2021, when the post of chairman of the Sovereignty Council, the highest decision-making body under the transitional democratic government, was about to be replaced by a pro-democracy group from the military, a military coup occurred, and effective military rule has continued since then. In response, new support from Western countries stopped, the economy was in turmoil, and people's lives were impoverished[4].

One year later, in December 2022, momentum was generated between the military and democratic factions to form a new transitional democratic government, and a "framework agreement" was formed to re-establish a transitional democratic government. Subsequently, in order to realize the "Final Agreement," the issues of "restoration of the Empowerment Dismantling Committee,” "implementation of the Juba Peace Agreement," “issue of the Eastern Track of the Juba Peace Agreement,” and “Transitional Justice” were resolved one after another, leaving only "Security Sector Reform" as the last issue. The last issue was the agreement on the integration of the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the RSF, particularly with regard to the timing of the integration. The SAF announced that the integration of the two would take place "within two years," but the RSF said that it would take 10 years, and tensions between them increased.

The direct trigger was the incident on April 12. On that day, the RSF dispatched 100 armed vehicles equipped with anti-aircraft guns and other weapons to Merowe Air Base in northern Sudan, explaining that they received "information that the Egyptian Air Force was sending fighter jets to the base to attack the RSF.” Although the authenticity of this information is uncertain, the incident resulted in a standoff between the SAF and the RSF in the city of Merowe, and tensions rose sharply. The deployment of the RSF to Merowe appeared to subside when the SAF broke up the RSF convoy. However, three days later, on the morning of April 15, fighting suddenly broke out in Khartoum, where the RSF not only took over Khartoum International Airport, but also raided the private residence of the SAF’s Supreme Commander, Burhan. This resulted in the bombing of Khartoum International Airport by its own air force aircraft.

What is happening in Sudan now?

Initially, it was thought that the fighting would be over in a few days. This is because of the overwhelming difference in military power between the SAF and the RSF; the SAF has air force aircraft, tanks, and other equipment, while the RSF’s basic units are pickup trucks equipped with firearms. However, the fighting between the two shows no signs of ending even after three months have passed. Rather, the RSF has not only made guerrilla-style attacks on major bases and ordinary houses in Khartoum and turned them into strongholds, but has also begun to make RSF soldiers live in houses that have been vacated by evacuation[5]. In addition to Russia, the military support to the RSF from behind the scenes by Middle Eastern countries is believed to be a factor in the RSF’s ability to continue fighting[6].

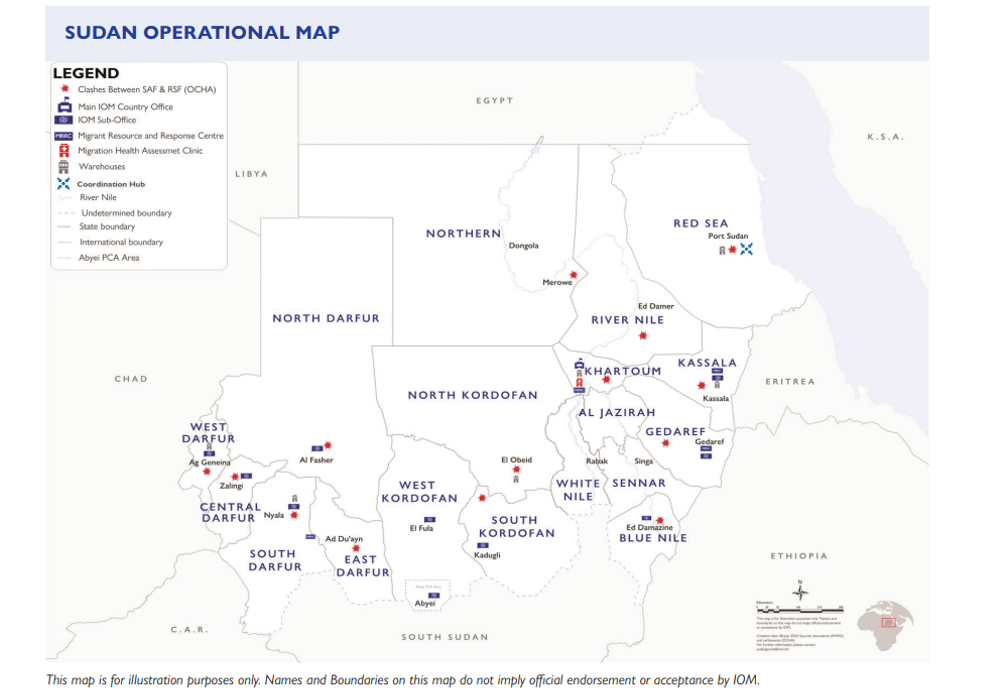

Initially, fighting between the RSF and the SAF took place in Khartoum, and Darfur in western Sudan, but the area of fighting has gradually expanded to include not only western Sudan but also southeastern regions such as Gedaref and Kassala[7]. In Kordofan in southwestern Sudan and Blue Nile in the south, another armed group, the SPLM-N Al-Hilu[8], has begun to fight against the SAF. The country is no longer able to maintain its security order.

Figure 1: Armed Clashes in Sudan (as of July 18, 2023)

In this situation, the UN and NGOs are providing humanitarian assistance, but in June the Sudanese government designated Mr. Volker Perthes, the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General of the UN Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan (UNITAMS), who was mediating for the ceasefire, as ‘persona non grata’[9] for "aggravating the military clashes in Sudan” and Mr. Perthes was barred from entering Sudan. This has forced the UN to reduce its influence toward a ceasefire in Sudan. In addition, humanitarian aid supplies are considered either by air-transport to Port Sudan by UN or other aircraft and then land-transport, or cross-border transport from Chad and other neighboring countries, but humanitarian aid workers have often been targets of attacks and looting, and have not been able to provide sufficient assistance. Many Sudanese government officials have also been evacuated from Khartoum, and the public service delivery system is not functioning.

What is the response of the international community?

In order to break out of this situation, the United States, along with Saudi Arabia, has attempted ceasefire negotiations from mid-May onwards, and reached several ceasefire agreements between the SAF and the RSF[10]; however, a full ceasefire was not implemented even during the agreed period and was not effective. The African Union[11] and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD)[12], a sub-regional organization in eastern Africa, have also been negotiating a ceasefire, but no concrete progress has been made as the SAF has refused these interventions.

At this juncture, Egypt turned to proactive diplomacy: on July 4 it improved relations with Turkey[13], with which it had been in a tense relationship for a long time, and on July 13 it convened a meeting of Sudan's neighboring countries to discuss a ceasefire in Sudan[14]. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), both deeply involved in the political situation in Sudan, are competing with each other to expand their influence in Africa[15]. The influence of these Middle East countries complicates the political situation in Sudan.

Why is this armed clash so dangerous?

Sudan has experienced many armed clashes in the past, but this clash is expected to have an impact unparalleled in the past.

The first point is the damage inflicted on the functions of the capital. Major facilities and infrastructure in the capital were destroyed by gunfire and airstrikes, and 2 million people have been evacuated in Khartoum State alone[16]. This corresponds to 40% of Khartoum's population of approximately 5 million people. RSF soldiers who have taken up residence in empty houses will not be easy to remove, even if the armed clashes end. Khartoum was home to wealthy Sudanese and intellectuals, but these groups who fled the country may not return to Sudan even after the ceasefire. Many RSF soldiers who start living in the vacant houses have been recruited from Darfur and neighboring countries, but if their stay is prolonged, they could become a major part of the Khartoum population in the future. This means that if an election is held, they would constitute a certain number of voters. The RSF was renamed from an armed group called the Janjaweed, which carried out massacres and burned villages in Darfur, to displace the local population and stay in their territories. The same approach is being taken now in the capital, Khartoum.

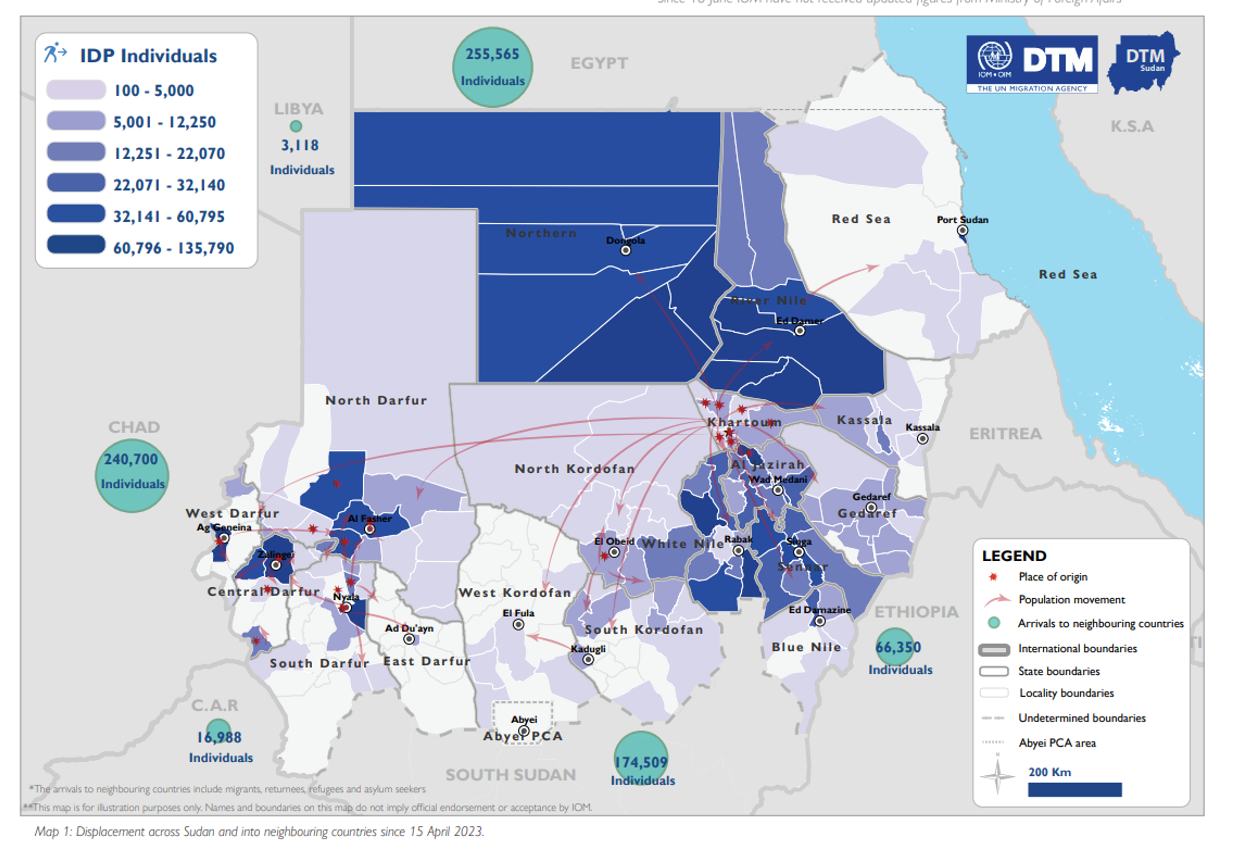

The second point is the impact that the armed clashes will have on the surrounding areas. 700,000 people have already fled to neighboring countries; 250,000 to Egypt, 240,000 to Chad, and 170,000 to South Sudan[17]. Egypt has long had a tolerant policy toward Sudan as its former colonial power, but has tightened restrictions on Sudanese entry into the country as the country's economy deteriorates. Chad is at risk of destabilization because a large influx of Sudanese could cause changes in its ethnic composition. Furthermore, Wagner, which has been operating in Sudan as well as the Central African Republic, may take advantage of the volatile situation in Sudan to strengthen its influence in these regions[18]. Eritrea has been strengthening its ties with Russia, which has become a source of concern as the situation in the entire "Horn of Africa" region becomes more fluid[19].

Figure 2: Sudanese Displaced Persons (as of July 18, 2023)

The third point is the retreat of democratization[20] and the proliferation of rule by violence in the region. Sudan's democratic movement has been sustained even under various crackdowns. However, since the armed clashes on April 15, the presence of pro-democracy groups has disappeared, and global attention has focused on the ceasefire between the SAF and the RSF. Before the military clash in April, the majority of public opinion favored “supporting the democratic group and disapproving of the military”. Since April, however, public opinion seems to have changed to "disapproving of the RSF and supporting the SAF”, as far as can be seen from the information circulating on SNS etc. If the current armed clashes end with RSF predominance, it is uncertain whether a country that the international community can support would emerge, but even if the clashes end in favor of the SAF, it is also not clear whether the democratization process that has long been taken place could continue. Besides, a core group of the former Bashir regime, known as the Islamists, is increasing its presence in the current armed clashes. The Islamists have been disbanded and barred from the political arena since the 2019 democratic revolution, but with the prolonged fighting between the SAF and the RSF, the Islamists have become an influential force in the process of the armed clashes[21]. It is apparent that the rise of the Islamists would become a major obstacle to promoting the democratization process.

This democratic backsliding and armed rule are expected to affect the growth of democracy not only in Sudan, but also in neighboring countries and on the African continent at large[22]. Can the international community create the momentum to defend and promote democracy, or will it be unable to take any effective measures against armed rule? It should be noted that quite a few security organizations and armed groups in politically fragile African countries are carefully watching future developments in Sudan, plotting coups and seeking opportunities for rule by force.

What should we do now?

Three months have passed since the military clashes, and the international community's interest in Sudan seems to have waned. However, as we have seen so far, the current military clash in Sudan is a turning point in the country's history, as it is an event that will determine whether Sudan can be recognized as a legitimate country by the international community and whether it can maintain its unity as a single nation. It is an event that will have a significant impact not only on Sudan, but also on the political systems in the Horn of Africa and other countries in Africa and the Middle East. This will inevitably affect the security policy and diplomacy of each country, including Japan.

In order to minimize this negative impact, we must first raise the international community's awareness of the situation in Sudan and create an environment in which all countries can work together to implement actions toward a peaceful resolution of this issue[23]. In addition, we need to build momentum to end the armed clashes, break away from military rule, and resume the process toward democratization.

Compared to the situation before the April military clashes, the democratization process is in a state of significant backsliding. However, halting the military clashes in Sudan and facilitating the democratization process are essential to maintaining trust with the people of Sudan, and with the people of other African countries, as we believe in and seek to promote the values of democracy.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not represent the official views of his organization.

(2023/08/24)

Notes

- 1 The Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) is the regular army of the Sudanese government and has trained soldiers as well as basic equipment such as air force aircraft and tanks. The RSF, on the other hand, is the organization renamed from the militia group, Janjaweed. The Janjaweed was a local armed group that sided with then-President Bashir in the 2003 Darfur conflict which took place in the Darfur region of western Sudan, and carried out massacres of local residents. Janjaweed was praised by President Bashir for its achievements in the Darfur conflict. In 2013, the group was given the name Rapid Support Force (RSF), and was allowed to station in the capital Khartoum as part of the government's security apparatus. It is believed that President Bashir intended to use the group as a counter-balancer to the national army's power accumulation by having another armed group in the capital.

- 2 “DTM Sudan Situation Report 13,” International Organization for Migration (IOM), July 18, 2023.

- 3 Nesrin Malik, “’All that we had is gone’: my lament for war-torn Khartoum,” The Guardian, July 18, 2023.

- 4 Koji Sakane, “One year after Sudan’s political turmoil: democracy and development are urgently needed,” The Sasakawa Peace Foundation, December 21, 2022.

- 5 “Sudanese City becomes Center of ‘New Phase’ of War”, New York Times, July 11, 2023.

- 6 Securing concessions in gold and other minerals held by the RSF and acquisition of a military base in the geopolitically important Red Sea are thought to be factors for the involvement of other countries.

Nima Elbagir et al, “Exclusive: Evidence emerges of Russia’s Wagner arming militia leader battling Sudan’s army,” CNN, April 21, 2023

“UAE behind RSF’s attempted coup in Sudan, leaked recording says,” Middle East Monitor, April 20, 2023.

Adam Lucente, “From UAE to Sudan: US targets Middle East entities for Wagner ties,” Al-Monitor, June 28, 2023. - 7 “Regional Sudan Response Situation Update,” International Organization for Migration (IOM), July 18, 2023.

- 8 The SPLM-N Al-Hilu faction is an armed group based in South Kordofan. It is one of the armed groups that have not participated in the Juba Peace Agreement. Although it had not been engaged in an overt armed struggle for several years, since April 2023 it has activated its military operations and recently it has made frequent attacks against the SAF.

“Rebel mobilization in southern Sudan raises fears of conflict spreading,” Reuters, June 9, 2023. - 9 “Sudan declares UN envoy Volker Perthes ‘persona non grata’,” Aljazeera, June 9, 2023.

- 10 Celine Alkhaldi,“Saudi Arabia and US announce Sudan 24-hour ceasefire,” CNN, June 9, 2023.

- 11 “Does Sudan need AU boots on ground?” PSC Report, Institute for Security Studies (ISS), June 7, 2023.

- 12 “Roundup: IGAD’s quartet committee fails to bring Sudanese warring parties to negotiating table,” China.org,cn, July 11, 2023.

- 13 Ezgi Akin, “Turkey, Egypt fully restore diplomatic ties after decade-long freeze,” AL-Monitor, July 4, 2023.

- 14 Edward Yeranian, “Egypt holds conference with Sudan’s neighbors on new cease-fire,” Voice of America, July 13, 2023.

“Sisi struggles to drum up interest in Sudan summit,” Africa Intelligence, July 12, 2023. - 15 Talal Mohammad, “How Sudan become a Saudi-UAE proxy war,” Foreign Policy, July 12, 2023.

- 16 “DTM Sudan Situation Report 13.”

- 17 ibid.

- 18 “Hundreds of Wagner fighters arrive in Central Africa: Russian security group,” Alarabia News, July 16, 2023; Alia Brahimi, “Mercenary bloodline: The war in Sudan,” Atlantic Council, July 7, 2023.

- 19 Joshua Meservey, “Eritrea’s growing ties with China and Russia highlight America’s inadequate approach in East Africa,” Hudson Institute, July 17, 2023.

- 20 Rahmane Idrissa, “Sudan’s repressed democracy,” The New York Review, July 18, 2023.

- 21 Khalid Abdelaziz, “Exclusive: Islamists wield hidden hand in Sudan conflict, military sources say,” Reuter, June 28, 2023.

Robert Bociaga, “How the Muslim Brotherhood could use Sudan’s protracted crisis to plot a comeback,” Arab News, June 16, 2023. - 22 “Sudan’s descent into violence poses new threat to volatile Sahel region,” Financial Times, July 17, 2023.

- 23 “Time to try again to end Sudan’s War,” International Crisis Group, July 21, 2023.