Introduction

This article follows the article, “The Third Battlefield Connected to Both Ukraine and Gaza: the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden ― The Houthis, Who are Continuing their Attacks on Merchant Ships, Versus the Navy Units of Foreign Countries which are Opposing the Houthis with Operations to Protect the Merchant Ships,”[1] which analyzed the naval activities of various countries working together to respond to indiscriminate attacks.

This article will analyze the reasons why Japan, where maritime shipping accounts for almost all trade volume, is not currently participating in the Combined Maritime Forces’ protection operations, or even conducting its own protection activities, instead limiting itself to information gathering. This analysis will be based in part on the current activities of the naval forces of various countries, including the Combined Maritime Forces that were analyzed in the previous article. This article will then consider what course Japan should take in the future.

Figure 1: Destroyer JS “Akebono” engaged in direct ship escort in the Gulf of Aden (November 2023)

1. Self-Defense Forces activities in maritime areas of the Middle East

1) Anti-piracy operations

When it comes to Japanese criminal law, international law cannot be directly incorporated into the domestic legal code. Because of that, piracy, which is a crime under international law, could not be prosecuted in Japan before the appropriate legal framework was put in place in July 2009, unless the ship that was attacked or the ship committing the crime was a Japanese ship. In this context, from 2008, 12 vessels related to Japanese companies have been attacked in the Gulf of Aden off the coast of Somalia, 5 of which were hijacked.[2] In response to this, policymakers in Tokyo began considering a law to address piracy under Japanese law.[3] However, in January 2009, the Japanese Shipowners' Association and the All-Japan Seamen's Union, which were concerned about the situation, strongly requested that Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF) ships be dispatched “within the framework of the current law” without waiting for new legislation.[4] In response to this request, the government decided to dispatch the MSDF to the waters off Somalia and the Gulf of Aden in March 2009 for Maritime Security Operations (MSO),[5] without waiting for the passage of the anti-piracy bill that was under consideration.

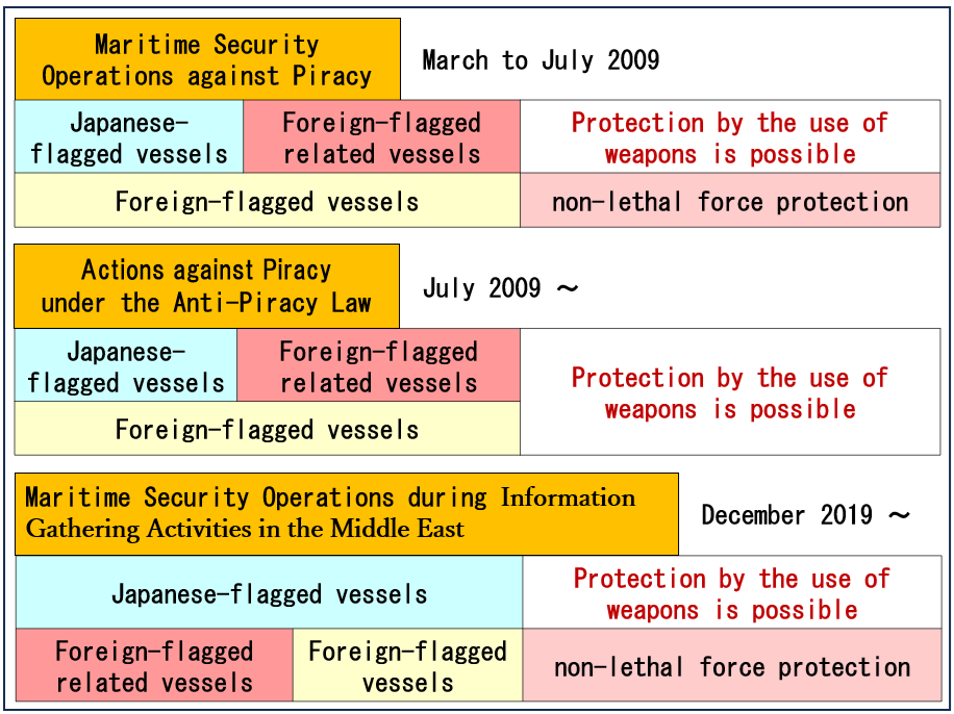

However, the government’s previous position was that only Japan-flagged vessels could be protected by MSOs.[6] In 2009, of the 2,535 vessels in the Japanese merchant fleet,[7] which is vital to Japanese shipping, only 107 (4.2%) were Japan-flagged, and most of the fleet was made up of foreign-flagged vessels.[8] Therefore, the MSOs could not, according to the government’s position, protect those foreign-flagged ships, which constitute the majority of the merchant fleet. The government therefore changed its interpretation of the law such that foreign-flagged vessels with a connection to Japan (hereafter, “Japan-related vessels”) could be protected by MSOs.[9]With the enactment of the Anti-Piracy Law on July 24, almost all acts of piracy were categorized as crimes under domestic law, and Japan became able to protect all merchant ships, including foreign-flagged vessels other than Japan-related vessels.

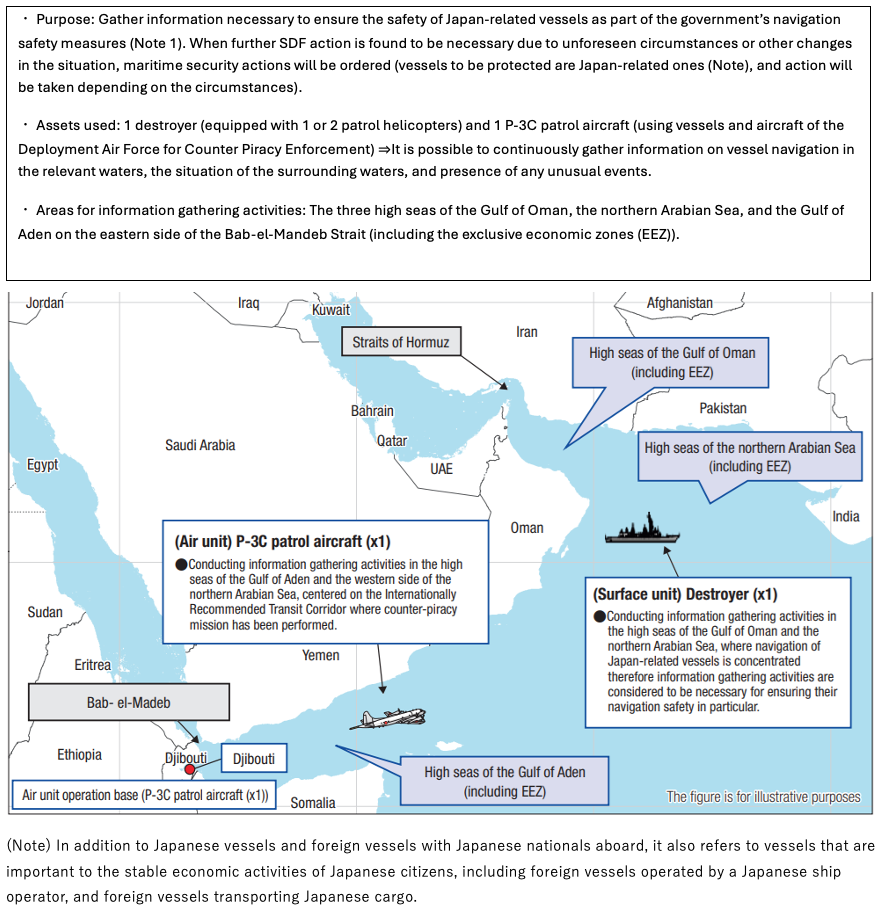

2) Information-gathering in maritime areas of the Middle East

While anti-piracy operations are ongoing, on June 13, 2019, two ships, including a Japan-related vessel, were damaged by the detonation of a limpet mine in the Gulf of Oman.[10] It is strongly suspected that the mine was deployed by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corp (IRGC).[11] Between this incident and September, there were four cases of capture and five cases of obstruction of navigation by Iran near the Strait of Hormuz.[12] The Iranian obstruction of navigation from June of that year may have stemmed from the Trump administration’s unilateral withdrawal from the Iran nuclear agreement and the resumption of sanctions against Tehran on May 8, 2018. In May 2019, the Trump administration ended the exemptions from secondary sanctions (such as exclusion from U.S. markets) that it had previously granted to major importers of Iranian oil, and tightened restrictions on Iran's oil exports and banking sector.[13] The Iranian economy, subjected to a series of sanctions, declined sharply, and the annual inflation rate rose fourfold, leading to protests.[14] Meanwhile, in response to Iran's obstruction of navigation, the United States formed the International Maritime Security Construct (IMSC) in November,[15] and in Europe, the European Maritime Awareness in the Strait of Hormuz (EMASoH) began operating in February 2020.[16]

Japan began dedicated consideration of information gathering in the Middle East in October 2019,[17] and on December 27 the government decided to use the SDF to gather information as a part of “the government’s efforts to ensure the safety of Japan-related vessels in the Middle East.”[18] Tokyo has therefore decided not to participate in the U.S.-led IMSC, but to take its own approach “while also taking into account relations with Iran.” This is not limited to Japan. Europe, for example, distanced itself from the hardline position of the U.S. and did not participate in IMSC, instead independently implementing EMASoH.[19] Additionally, in response to the U.S. and U.K.'s attacks on Yemeni territory in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, the European Union withdrew from the U.S.-led commercial ship escort operation (Operation Prosperity Guardian) and established its own operation (Operation Aspides) to be more in line with attitudes in the EU.[20]

Figure 2: SDF intelligence-gathering activities (image)[21]

2. Protection of Japanese commercial vessels

1) Legal characteristics of Japan

Looking at CENTCOM's public statements, other countries refer to the several attempts to capture manned ships as “piracy,” but CENTCOM fights back against the Houthi's unmanned weapons attacks on the basis of “self-defense.”[22] This “self-defense” is not the “right of self-defense” based on Article 51 of the UN Charter, but is understood as “the use of force” as “proportionate counter-measures” against “the use of force of a lesser degree of gravity [than an armed attack]” as indicated by the International Court of Justice in 1986.[23] In contrast, under the interpretation based on the Japanese constitution, the “use of force” is limited to defense deployments of the SDF, so the use of force as a “proportionate counter-measure” under international law is not “self-defense,” but rather is classified as a police authority under Japanese domestic law. As a result, even though the SDF can protect its own and U.S. forces during peacetime, it is placed in an irrational position in which it cannot even protect Japanese vessels without being granted police powers by government order, including anti-piracy operations and MSOs. This is a major constraint on the SDF’s current protection of commercial vessels. Moreover, Article 101 of UNCLOS defines piracy as “any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any act of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft,” and Article 2 of Japan’s Anti-Piracy Law largely defines piracy the same way.[24] Based on this provision, it is not possible to use the Anti-Piracy Law to protect against attacks from drones and missiles launched from Yemeni territory, unmanned surface vessels, or unmanned underwater vessels. However, MSOs allow for the elimination of attacks by missiles, drones, and so on, with the exception of ballistic missiles.[25]

2) The current status of Japanese protection of commercial vessels

In contrast to the European and American initiatives, Japan in 2019 decided not to protect commercial vessels, stating the waters near the Strait of Hormuz were not “in a situation in which Japanese vessels needed immediate protection,” and that if an unforeseen situation made such protection necessary, it would be done through the issuance of a MSO order.[26] The official position behind this decision is that the use of weapons against a state or an organization equivalent to a state may constitute the use of force, which is forbidden by the Japanese constitution.[27] If one were to guess at the motivations behind this, the thinking appears to be that because the IRGC, the main actor in maritime obstruction operations, is a part of a state military, Japan should avoid conflict with it as much as possible. This would seem to be a reasonable assessment, judging from the nature of the obstruction at the time and the examples of responses from other countries.[28][29]

However, the situation in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden today is very different from that around the Strait of Hormuz, which was the subject of the 2019 decision. In the vicinity of the Strait of Hormuz, the threat of capture by the IRGC, an Iranian state agency, was the main concern. The threat in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, however, is indiscriminate attacks on ships by drones and missiles from the Houthis, a non-state actor, and other countries are eliminating this threat through force. Considering this, there is no way that the original decision, which was made regarding the Strait of Hormuz in 2019, that “Japanese vessels [do not need] immediate protection” can be rationally applied to the current conditions in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

Moreover, there are questions about the Japanese government’s position on the protective measures for Japan-related vessels through MSOs. While maintaining the view that Japan-related vessels are eligible for protection through MSOs, the government has made a significant change to the 2009 interpretation, which expanded the scope of vessels that can be protected through the use of weapons. In the written response to a question posed on February 27, 2020,[30] the government said that when protecting Japan-related vessels, the basic approach would be to act based on the flag state principle, and that “generally, international law does not establish the concept that, if the flag state of a foreign-registered ship on the high seas agrees, a third-party country other than the flag state can use force against a vessel carrying out infringement that does not amount to an armed attack on the foreign-registered ship in order to eliminate that infringement.”[31] This is based on the flag state principle, which was not raised in the 2009 interpretation that expanded the scope of protected ships, meaning that the use of weapons is limited to attacks against Japan-flagged vessels, and Japan-related foreign-flagged vessels can be protected only through measures that do not involve the use of force, just as other foreign-flagged ships (see Figure 3).[32]

The aforementioned question asked, “Under the flag state principle in international law, is the issue not the nationalist of the vessel that commits infringement or other illegal acts, rather than the nationality of the damaged vessel?”[33] However, the government has not provided a clear position on this point.[34]

Article 98, paragraph 1 of UNCLOS also stipulates the requirement to lend mutual assistance at sea, where there are few other people, stating, “Every State shall require the master of a ship flying its flag … to render assistance to any person found at sea in danger of being lost,” and it is common practice in the international community to board ships to provide assistance in response to a request from the captain of a ship in an emergency situation.[35] Viewed in this light, questions remain about the change that excluded the use of weapons from the protection of foreign-flagged Japan-related vessels on the grounds of the flag state principle.

Figure 3: Changes in the interpretation of protected vessels

Conclusion

Naval forces in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden act in accordance with the policies of their respective countries, but in general they act to eliminate the threat of attacks, regardless of the state flag of a vessel in distress. In contrast, the protection offered by the SDF requires the determination of whether the type of infringement and the vessel to be protected are covered by the government order, followed by the elimination of the infringement. Therefore, enabling the SDF to protect all ships during peacetime will require new legislative measures, similar to the Anti-Piracy Law, but it will be extremely difficult to enact such a law in Japan’s current legislative environment. On the other hand, the change in interpretation that excludes the use of weapons in the protection of foreign-flagged Japan-related vessels it not a problem limited to the Middle East, but rather an issue regarding the authority to use weapons in all MSOs. This impacts the protection of all Japan-related vessels, so an immediate review of the interpretation is needed. Furthermore, rather than only addressing unforeseen situations, the government should follow the example of the 2009 anti-piracy operations and grant the SDF the authority to use weapons in MSOs at all times.

(2024/10/21)

Notes

- 1 Susumu Nakamura, “The Third Battlefield Connected to Both Ukraine and Gaza: the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden ― The Houthis, Who are Continuing their Attacks on Merchant Ships, Versus the Navy Units of Foreign Countries which are Opposing the Houthis with Operations to Protect the Merchant Ships,” Sasakawa Peace Foundation, International Information Network Analysis, July 29, 2024.

- 2 “Piracy Issues Off the Somali Coast and in the Gulf of Aden,” Japanese Shipowners’ Association, April 1, 2010, p. 1.

- 3 Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Kazuyoshi Kaneko, “Record of the 171st National Diet House of Representatives Budget Committee Meeting,” No. 15, February 18, 2009, p. 6.

- 4 “Joint Statement with the All-Japan Seamen's Union on the Issue of Piracy in the Gulf of Aden,” Japanese Shipowners' Association and All-Japan Seamen's Union, January 9, 2009.

- 5 Defense of Japan 2014, p. 296.

- 6 Director of the Ministry of Defense Operational Planning Division Hideshi Tokuchi, “Record of the 171st National Diet House of Representatives Security Committee Meeting,” No. 2, March 13, 2009, p. 3.

- 7 The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, the Shipowners' Association and other maritime-related organizations refer to the group of ocean-going merchant ships operated by Japanese shipping companies, which consists of Japan-flagged ships and foreign-flagged ships chartered from foreign companies, as the “Japanese merchant fleet.” “The Japanese Merchant Fleet,” Japanese Shipowners' Association, Glossary of Maritime Terms, April 1, 2017.

- 8 “Figure 1-23: Changes in the Composition of the Japanese Merchant Fleet,” Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Maritime Affairs in Figures 2023, 2023, p. 16.

- 9 See Note 6.

- 10 On April 8, 2018, the U.S. government designated the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and one of its branches, the Quds Force (IRGC-QF), as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs), marking the first time that the US government has designated a part of another country's government as an FTO. “Statement from the President on the Designation of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps as a Foreign Terrorist Organization,” The White House, April 8, 2019.

- 11 On June 13, 2019, then-U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo strongly indicated Iran's involvement when he said, “It is the assessment of the U.S. government that Iran is responsible for the attacks that occurred in the Gulf of Oman today.” Congressional Research Service Report (R45795), September 17, 2019, p.3.

- 12 Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, “Discussion Points for Formulating a New International Resources Strategy,” October 4, 2019, p. 28.

- 13 Until the sanctions in May 2019, the U.S. had granted exemptions from secondary sanctions to the eight major importers of Iranian oil, including Japan. “Six charts that show how hard US sanctions have hit Iran,” BBC, December 9, 2019.

- 14 “Iran oil: US to end sanctions exemptions for major importers,” BBC, April 23, 2019.

- 15 The IMSC was established as a coalition to monitor threats from Iran, and as of November 2023, there are 12 participating countries, including the U.S. and the U.K. “United States Central Command,” Congressional Research Service, February 13, 2020, p.2.

- 16 An organization with nine participating countries, including France, Germany, and Italy. “About EMASoH/ Agenor,” European Maritime Awareness in the Strait of Hormuz, accessed on August 24, 2024.

- 17 Press Conference by the Chief Cabinet Secretary on “Peace and Stability in the Middle East,” October 18, 2019.

- 18 The government's rationale for dispatching the SDF was that it was necessary “to conduct research to carry out the affairs under its jurisdiction,” as stipulated in Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 18 of the Act for Establishment of the Ministry of Defense. “Regarding the Government's Efforts to Ensure the Safety of Japan-related Vessels in the Middle East Region,” National Security Council Decision/Cabinet Decision, December 27, 2019.

- 19 Geir Ulfstein, “How International Law Restricts the Use of Military Force in Hormuz,” EJIL Talk!, August 27, 2019.

- 20 Léonie Allard, Cinzia Bianco, and Mathieu Droin, “With Operation Aspides, Europe is charting its own course in and around the Red Sea,” Atlantic Council, March 7, 2024.https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/with-operation-aspides-europe-is-charting-its-own-course/#:~:text=Léonie%20Allard%20is%20a%20visiting%20fellow%20at%20the%20Atlantic%20Council’s

- 21 Japan has long been engaged in intelligence-gathering activities as part of its anti-piracy efforts, but these were limited to the Somali coast and the Gulf of Aden. The government therefore issued a new decision to “gather intelligence in the Middle East” that also covered the Strait of Hormuz and the Gulf of Oman. Initially, one new destroyer was dispatched to gather information together with patrol aircraft engaged in anti-piracy operations, but currently, only one destroyer and one patrol aircraft engaged in both anti-piracy operations are engaged in intelligence-gathering activities.

- 22 For example, CENTCOM’s public statement said, “CENTCOM forces conducted self-defense strikes against two anti-ship cruise missiles that presented an imminent threat to merchant vessels and U.S. Navy ships in the region.” However, a series of websites that referred to the interception at sea as “self-defense” have now been deleted. It is thought that this was to avoid confusion with the “exercise of the right of self-defense” in the context of attacks within Yemeni territory. “March 4 Red Sea Update,” USCENTCOM, March 4, 2024.

- 23 “Nicaragua v. United States of America,” ICJ. Reports, June 27, 1986, para. 191, para. 249.; this judgment is silent on whether “counter-measures” include the “use of force,” but it is generally recognized in the international community that they do, and Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs also supports this interpretation. “Record of the House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee,” No. 4, September 18, 1998, p. 14.

- 24 Japan’s Anti-Piracy Law does not include aircraft within its scope, on the grounds that there has been no actual situation in which pirates have used aircraft.

- 25 “Yemen: MSDF destroyer leaves area at maximum speed after receiving information about missile launch,” NHK, November 29, 2023.

- 26 “Record of the 200th National Diet House of Representatives Security Committee Meeting,” No. 2, October 24, 2019, p. 3.

- 27 “Regarding the Development of a Seamless Security Legislation to Ensure the Existence of the Nation and Protect Its Citizens,” National Security Council/Cabinet Decision, July 1, 2017.

- 28 For example, the U.K.’s Royal Navy responded to the IRGC's attempts to capture U.K.-flagged oil tankers on July 10 and July 22, 2019, but in both cases it attempted to eliminate the threat through warnings only, without using any force. On the 10th it was able to intercept the threat in time, but on the 22nd it was unable to prevent the tanker from being captured because it was too far away. “Strait of Hormuz: Iranian boats 'tried to intercept British tanker',” BBC, July 12, 2019; “Iran tanker seizure: UK 'didn't take eye off ball', Hammond says,” BBC, July 22, 2019.

- 29 “Questionnaire on the Protection of Japan-Related Vessels in the Middle East and the Principle of Flag State Jurisdiction under International Law” February 27, 2020.

- 30 “Written Response to Questions Submitted by Shinkun Haku, Member of the House of Councillors, on the Protection of Japan-Related Vessels in the Middle East and the Principle of Flag State Jurisdiction under International Law”, March 10, 2020.

- 31 Minister of Defense Taro Kono, “Record of the 201st National Diet House of Councillors Budget Committee Meeting,” No. 12, March 17, 2020, p. 13.

- 32 See Note 29.

- 33 See Note 30.

- 34 For example, on January 26, 2024, the Indian Navy boarded an oil tanker that had caught fire after being hit by a Houthi anti-ship ballistic missile and extinguished the fire. Indian Navy post on X (January 28, 2024). “Fire onboard MV #MarlinLuanda brought under control,” SpokespersonNavy@indiannavy, January 28. 2024