1. Introduction

There is growing interest in how Japan would respond to a contingency involving Taiwan. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, in his report on government activities at the National People’s Congress delivered on May 22, 2020, removed the word “peaceful” from the section addressing “reunification” with Taiwan, suggesting a possible change in policy[1]. Furthermore, Chinese military aircraft entered Taiwan's Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) more than 380 times last year, according to Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense (MOD). Then, as if to test the new Biden administration in the U.S., 13 military aircraft flew into the ADIZ on January 23, immediately after its inauguration, and 15 did the same on the following day[2]. The intimidating flights have not stopped since, with Chinese military aircraft entering the ADIZ more than 20 times in May, according to the MOD[3].

At a U.S. Congressional hearing in March, Philip Davidson, then commander of the Indo-Pacific Command, said that a Chinese invasion of Taiwan could happen in the “next six years,” and his successor, John Aquilino, said it is “much closer to us than most think”[4]. Behind these concerns, there are also worries about the delayed deployment of U.S. military forces in response to China’s growing military power[5]. According to a comparison of U.S. and Chinese forces in the Western Pacific as of 2025, China is expected to have three aircraft carriers deployed to the U.S.’ one, 108 multi-functional warships to the U.S.’ 12, six times as many submarines, and nine times as many warships. Regarding fighter jets, China has 1,250 fighters compared to the U.S.’ 250, and it plans to have 1,950 by 2025, nearly eight times more than the U.S. total. Additionally, China’s ballistic missiles also pose a major threat to naval forces approaching the area.

The U.S. overall has an advantage over China, including Washington’s 11 aircraft carriers, but even if it deploys forces from the west coast or Alaska, it would take two to three weeks for them to reach the first island chain that stretches from the Japanese archipelago to Taiwan and the Philippines. That makes it difficult to overcome the numerical advantage China maintains by virtue of geography. Given these conditions of relative power, it is no longer feasible for the U.S. alone to support Taiwan in the event of a crisis. Japan, which hosts important U.S. military bases, is in a position to take part in such a crisis.

In addition to emphasizing the “the importance of peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait” in the joint statement at the March 16 “two-plus-two” meeting (security consultations between the foreign and defense ministers), Japan and the U.S. went further in the statement at the April 16 leaders’ summit, adding the phrase, “encourage the peaceful resolution of cross-Strait issues.” This was the first time since 1969, before the normalization of diplomatic relations between Japan and China, that “Taiwan” appeared in the joint statement from a Japan-U.S. leaders’ summit.

This article will review Japan’s legal framework for addressing contingencies, and then, with a Taiwan contingency in mind, examine Japan’s response to each stage of a crisis as it develops from its initial stages into armed conflict, and what it should do to prepare.

2. Japan’s contingency legislation system

The actions of the armed forces of other countries generally involve cross-sectional responses to situations ranging from peacetime to wartime. In contrast, the actions of the Japan Self-Defense Forces are based on legal principles that enumerate its responses and authorities by action. This is the so-called “positive list” format[6]. For situations that affect Japan’s peace and security, it is designed as a “contingency management system” that classifies responses according to the situation.

Japan’s development of laws to handle “contingencies” began in 1999 with the “Emergency-at-Periphery Law,”[7] which responded to the post-Cold War shift of threat probability from direct armed attacks against Japan to emergencies occurring in the area around the country that could then spread to Japan. In 2003, the “Armed Attack Situation Response Law” was established to provide a framework for dealing with armed attacks, an area that had been neglected for roughly 50 years after World War II[8].

With the 2015 Peace and Security legislation, the “Law on Important Influence Situations”[9] was amended to remove the limitations in the Emergency-at-Periphery Law that restricted the scope of responses to the area around Japan. The 2015 legislation also added “existential crisis situations”[10] to the Armed Attack Situation Response Law. At this point there were five categories of situations that could impact Japan’s peace and security: “critical impact situations,”[11] “emergency response situations,”[12] “anticipated armed attack situations,”[13] “armed attack situations,”[14] and “survival-threatening situations.” It also laid out “joint international peace response situations,”[15] in which Japan proactively addresses situations that threaten the peace and security of the international community[16].

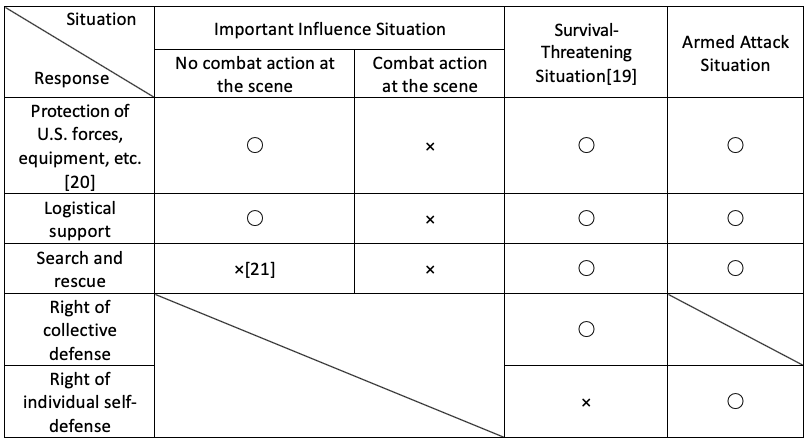

The measures taken by the SDF in each situation are stipulated in individual laws, as well as in Article 76 (defense operation)and Article 84-5 (logistical support, etc.) of the Self-Defense Forces Law[17], and are broadly classified into "important influence situations," "emergency response situations," "anticipated armed attack situations," and "joint international peace response situations," all of which do not involve the use of force. There are also "survival-threatening situations" and "armed attack situations," which do involve the use of force and require authorization from the Diet.

3. Different scenarios and Japan’s responses

A Taiwan crisis is not expected to be classified as a “ship inspection operation”[18] based on economic sanctions, or a “joint international peace response situation.” It would instead likely be categorized as a “important influence situation” or a “survival-threatening situation,” depending on circumstances. Furthermore, if the situation spread to Japan, it would be recognized as an “armed attack situation.” However, considering Japan’s political environment, with its still deeply rooted “pacifism” and “consideration for China,” it is not always simple to immediately apply institutional categorizations for situations to reality. Therefore, the following is a discussion of Japan’s response to each scenario (see the table below for each type of situation and the SDF’s response).

1) Before armed conflict

Currently Japan and the U.S. are conducting ongoing vigilance and surveillance in the East China Sea and sharing information. Therefore, if the U.S. deploys troops in the vicinity of Taiwan, both Japan and the U.S. will strengthen their vigilance and surveillance in the East China Sea, or, depending on the concentration of U.S. troops around Taiwan, the SDF will strengthen its current vigilance and surveillance in a supplementary manner.

If the U.S. concentrates its forces in the waters around Taiwan, supply support for the troops will be essential. If the situation turns tense, one cannot expect the ASEAN countries, which are concerned about their relations with China, to permit U.S. ships to make port calls for supplies. The U.S. forces may stop in Taiwan, but if their deployment is prolonged, they will need supply support at sea. In this case Japan’s support will be indispensable, as it can send supply forces back and forth from nearby Okinawa. For the SDF to provide supply support to U.S. forces, authorities must declare a “important influence situation.” Additionally, the declaration of a “important influence situation” allows for relevant administrative organizations other than the SDF to take “response measures,” and requests for cooperation from entities other than the government can be made[22].

2) Development into armed conflict

If the situation develops into an armed conflict, the “important influence situation” would continue if already declared, or one would be declared if it had not been so already. Japan would support the U.S. forces that have become party to the conflict (and those of other countries participating). However, under a “important influence situation” the SDF will be unable to take “response measures” at the site of actual combat operations[23], nor will it be able to “defend U.S. forces.” Article 95-2 of the SDF Law, which is the basis for "defending U.S. forces," stipulates that the "protection of U.S. forces shall exclude locations where combat activities are currently occurring," and an attack on U.S. forces at this stage is itself a "combat activities”[24]. But with the reported threat of China’s anti-ship missiles, missile protection by the SDF will be an important form of support. Therefore, if the protection of U.S. forces is required, it is necessary to immediately declare a “survival-threatening situation.”

3) China’s attack spills over to Japan

The U.S. forces dispatched to the area around Taiwan will primarily consist of troops from U.S. military bases in Japan, such as Okinawa, Yokosuka, and Sasebo. In addition to the U.S. bases, Japanese ports and harbors, which are important rear bases, could become targets of Chinese attacks. In this case, Japan can declare an “anticipated armed attack situation” and issue a “defense convocation order” and a “standby order for deployment.” Furthermore, Japan could recognize an "armed attack situation" and order a "defense deployment" when there is a clear and imminent danger of an armed attack, and it could invoke the right of self-defense when an armed attack occurs[25].

4. How should Japan prepare?

Finally, I would like to examine the issues that need to be considered in Japan’s response to a Taiwan crisis, and pose some questions regarding their resolution. As previously mentioned, China holds the military advantage in the Pacific, and it will be difficult for the U.S. military to address a situation on its own.

1) Obstacles to declaring a situation

A key factor in declaring a “important influence situation” or a “survival-threatening situation” will be the presence or absence of countries other than the U.S. that are helping Taiwan. However, China’s crackdown on democratic protests in Hong Kong has raised international alarm over Chinese hegemony, and the U.K., France and Canada have dispatched naval forces to the South China Sea as a part of the U.S.’ freedom of navigation operations. Germany has expressed its intent to do the same. In this context, the U.S. has high expectations of Japan and Australia in particular. However, if no country other than the U.S. is willing to support Taiwan, and if Japan is the only one to aid the U.S. in opposing China, confusion over declaring a contingency is inevitable. In addition to the fact that neither a “important influence situation” nor a “survival-threatening situation” has ever been declared before, confusion in domestic debate will likely make it even more difficult for the government to make quick decisions.

In addition, legally a “survival-threatening situation” is defined as “an attack on another country with a close relationship to Japan.” It could therefore be argued that Taiwan, which does not have formal diplomatic relations with Japan, is neither “close” nor is it a “country.” However, the government was previously asked, “Is ‘other countries’ limited to countries with which Japan has diplomatic relations, or does it include territories with which Japan does not have diplomatic relations but in reality are widely regarded as countries (such as Taiwan and the Palestinian Authority)?” The government responded, saying, “Countries with which Japan does not have diplomatic relations can but included, but it is difficult to answer this question because the meaning of ‘regarded as countries’ is not always clear”[26]. Officials need to prepare a manual that standardizes contingency procedures in line with this government view.

Furthermore, in the case that an “armed attack situation” was declared and the SDF was deployed in response to an attack by China, the SDF forces in the field would only be able to fight back using weapons under police authority, which could result in an enormous disadvantage. For this reason, a deployment order must be issued at an earlier stage so the SDF can immediately invoke the right of self-defense (the use of force) to fight back in the event of an attack[27].

2) Urgent issues for quick and accurate decision-making

In times of national emergency, timely and accurate decision-making is critical. In the current response to the COVID-19 pandemic various issues have emerged regarding the timing of declaring a state of emergency. This common problem of “situational awareness” was also noted in the September 2010 collision of a Chinese fishing boat with an SDF patrol boat, and in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. The speed of decision-making in “situational awareness,” the topic of this article, is extremely important. In the COVID-19 response, there have been not only decision-making issues, but also contingency response problems, such as establishing waiting areas for people with minor infections. The problems revealed by these precedents must be examined in detail later so these substantial problems can be resolved.

Usually the success or failure of decision-making lies in information. Although decision makers often seek more information, it is important to sort out the information that is essential for decision-making and that which can be used for reference. Without this process decision-making will be prolonged because of the confusion caused by a flood of information. It is also necessary to develop processing procedures for decision-making based on this information. Sharing these preparations from the Prime Minister’s Office to the people in the field will enable those on the ground to know the reporting priority, which will in turn lead to quicker decision-making.

Most importantly, however, even if procedures and manuals are prepared and information is obtained, decision-making is not something that can happen suddenly if one is not familiar with the process. Therefore, it is necessary to establish decision-making mechanisms and conduct exercises at all levels, from in-the-field where personnel directly deal with a contingency to the Prime Minister’s Office where final decisions are made[28].

(2021/06/15)

Notes

- 1 Yew Lun Tian, Yimou Lee, “China drops word 'peaceful' in latest push for Taiwan 'reunification',” Reuters, May 22, 2020.

- 2 “China flies warplanes close to Taiwan in early test of Biden,” CNN, January 25, 2021.

- 3 Simon Lee, “Taiwan Detects Chinese Jet in Air Defense Zone on May 4,” Bloomberg, May 4, 2021. (Japanese)

- 4 Brad Lendon, “Chinese threat to Taiwan 'closer to us than most think,' top US admiral says,” CNN, March 25, 2021.

- 5 Statement of Admiral Philip S. Davidson, U.S. Navy Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on U.S. Indo-Pacific Command Posture, U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Service, March 9, 2021,pp.32-37; Hiroyuki Akita, “Future balance of power haunts US as China bulks up,” Nikkei Asia, March 16, 2021.

- 6 Generally, in debates about laws and regulations governing the actions and authority of the SDF, the format of “only permissible actions are stipulated, and what is not stipulated is not permissible” is referred to as the positive list format. The format of “only impermissible actions are stipulated, and what is not stipulated is permissible” is known as the negative list format.

- 7 “Act on Measures to Ensure the Peace and Security of Japan in Perilous Situations in Areas Surrounding Japan.” Cabinet Office for National Security Affairs and Crisis Management, Defense Agency, and Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Commentary on Article 9 (Cooperation of Local Governments and the Private Sector) of the Emergency-at-Periphery Law,” July 25, 1999. (Japanese)

- 8 Formally, “Act on the Peace and Independence of Japan and Maintenance of the Nation and the People’s Security in Armed Attack Situations, etc.,” At the time of its enactment, the “Armed Attack Situation Response Law” was called the “Act for Dealing with Emergencies.” Cabinet Secretariat, “The ‘Act for Dealing with Emergencies’ Enacted in the 2003 Regular Diet Session,” Civil Protection Portal Site (accessed May 22, 2021). (Japanese)

- 9 Law Concerning Measures to Ensure the Peace and Security of Japan in Situations that Will Have an Important Influence on Japan’s Peace and Security. (Japanese)

- 10 With the addition of " survival-threatening situations," the name of the law was changed to the "Act on the Peace and Independence of Japan and Maintenance of the Nation and the People’s Security in Armed Attack Situations, etc., and a Survival-Threatening Situation," and the term "survival-threatening situation" was defined in Article 2, Item 4 as " a situation where an armed attack against a foreign country that is in a close relationship with Japan occurs, which in turn poses a clear risk of threatening Japan's survival and of overturning people's rights to life, liberty and pursuit of happiness fundamentally.” (Japanese)

- 11 “Situations that will have an important influence” refers to situations that will have an important influence on Japan’s peace and security, including situations that, if left without response, could lead to a direct armed attack on Japan," Law on Important Influence Situations, Article 1. (Japanese)

- 12 Article 21 of the Armed Attack Situation Response Law also stipulates "emergency response situations" to deal with the occurrence of large-scale terrorism other than the use of force. (Japanese)

- 13 A tense situation that has not yet reached the level of an "armed attack situation," but where an armed attack is predicted, and a standby order for deployment can be issued. Armed Attack Situation Response Law, Article 2, Item 3. (Japanese)

- 14 "Situations in which an armed attack against Japan from outside occurs or in which it is considered that there is an imminent and clear danger of an armed attack.” Armed Attack Situation Response Law, Article 2, Item 2. (Japanese)

- 15 Act on Cooperative Support Activities for Foreign Armed Forces, etc. Conducted by Japan in the Event of a Joint International Peace Response Situation. (Japanese)

- 16 Cabinet Secretariat, “Development of the Peace and Security Legislation, etc.” (accessed on May 22, 2021) (Japanese)

- 17 While the SDF's actions and authority are stipulated in these individual laws, the SDF Law also contains some fundamental rules. This is based on the idea that the SDF Law, the basic law of the SDF, must cover all provisions related to the SDF's actions, authority, and so on. Such provisions are called index provisions, and they can be found in disaster response, PKOs, anti-piracy operations, etc., as well as in laws related to contingency planning.

- 18 Act on Ship Inspection Activities to be Conducted in the Event of a Significant Impact Situation, etc., Article 2. (Japanese)

- 19 "Logistical support," "search and rescue," and " protection of U.S. forces, equipment, etc." in an "existential crisis situation" are not "response measures" based on the Important Influence Law, but fall under the "use of force" based on Article 88 of the SDF Law. Regarding the limits on the exercise of the right of collective self-defense in an "existential crisis situation," the government states, "The participation of the SDF in the battles of the former Gulf War, i.e., large-scale aerial bombardment, artillery shelling, or the invasion of enemy territory, for the purpose of exercising armed force, is beyond the scope of the minimum necessary self-defense measures and is not permitted under the Constitution. Therefore, we believe that conducting actions like large-scale airstrikes to secure air or maritime superiority does not satisfy the new three requirements.” Official Gazette, Minutes of the House of Councillors of the 189th Diet, No. 34, July 27, 2015, p. 7.

- 20 SDF Law, Article 95-2 (use of force for the protection of the U.S. armed forces, etc.). (Japanese)

- 21 Under the Important Influence Law, search and rescue operations are to be conducted for “combatants in distress due to combat operations” (Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 2), and "combat operations" are defined as "acts of killing or injuring people or destroying property committed as part of an international armed conflict" (Article 2, Paragraph 3). Therefore, search and rescue operations in situations that are not “armed conflict” are not anticipated.

- 22 “Law on Important Influence Situations,” Article 8, Article 9. (Japanese)

- 23 Ibid. (Japanese)

- 24 See SDF Law, Article 95-2, Note 20.

- 25 Article 76, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the SDF Law allows for the mobilization of defense forces not only "in the event of an armed attack from outside," but also in situations where there is an "imminent danger of such an attack.” Therefore, even if a "defense deployment" is ordered, it does not mean that the SDF will use force if there has not been an armed attack. In addition, even if an armed attack occurs and a defense mobilization is issued, the SDF cannot use force until there is a separate order to use force (Article 76 of the SDF Law only stipulates the prime minister's authority to order a defense mobilization, and there is no specific provision on the procedure to order "activation of the right of self-defense" (use of force by the SDF). Therefore, this authority is included in the authority of the Prime Minister under Article 76.)

- 26 “Response to a Question from Counsellor Kenichi Mizuno,” Naikaku San Shitsu 189, No. 202, July 21, 2015. (Japanese)

- 27 cf. note 25.

- 28 Nobukatsu Kanehara, a special visiting professor at Doshisha University, who held key government decision-making positions, such as director general of the International Law Bureau at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, deputy assistant secretary of the Cabinet Secretariat, and deputy director general of the National Security Council, said, “Every country conducts ministerial-level training based on the highest level of war scenarios. Japan tends to be criticized if it tries to do so, with critics saying, ‘Are you planning to go to war?’” He also said, “It’s strange to net even raise the idea of having the Prime Minister’s Office, ministries and agencies, and personnel in the field train in anticipation of emergencies.” “Japan’s Drastically Changing Security Environment: ‘Now’ Is the Time to Protect the Nation,” Wedge, June 2021 issue. May 20, 2021, p. 35.