Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida will be invited to the Washington NATO summit to be held in July 2024, the third consecutive year the Japanese premier has been invited[1]. While this summit will focus on the alliance's commitment to further support Ukraine against the threat of Russia's ongoing war, NATO will also make significant progress in strengthening its future defence posture in a changing geopolitical environment. What does this mean for Japan as a global partner of NATO?

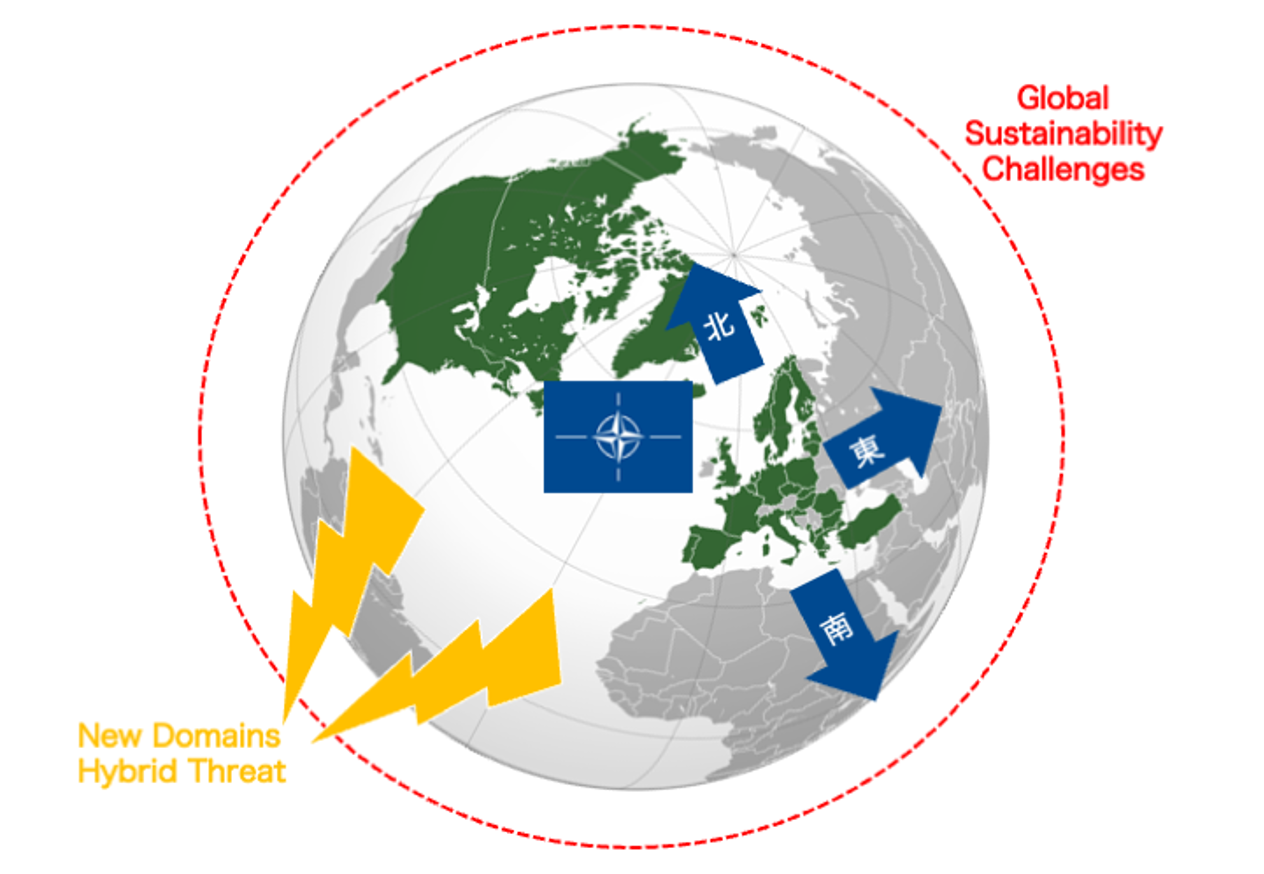

Chart 1:NATO’s 360-degree approach

NATO’s 360-degree approach

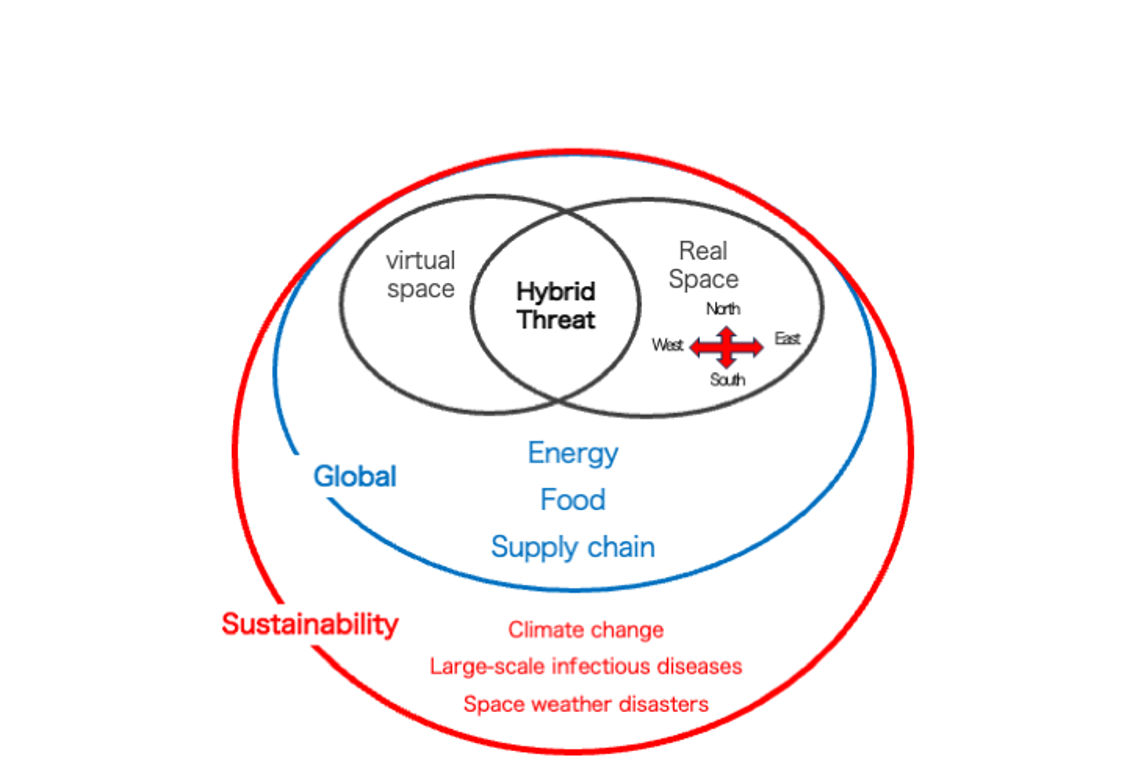

Since the Madrid Summit in 2022, NATO has begun to build a 360-degree approach to deterrence and defence posture, i.e. a cross-domain, seamlessly integrated deterrence and defence posture against threats from all directions (east, west, north and south), as well as from new domains such as the cyber, space and cognitive fields. Already, with regard to the approach to the 'East', the NATO Response Force (NRF) of up to 40,000 troops, comprising multinational land, sea and air forces, has been deployed for the first time for deterrence and defence missions against the Russian threat of an armed invasion of Ukraine, and an 'enhanced Forward Presence' (eFP) is in place in the Baltic States and Poland, on the eastern flank of the NATO[2].

In addition, for critical operational situations posed by hybrid threats[3] of new domain origin, NATO has been working towards strengthening the resilience of its societies and forces, alongside its readiness to respond with speed since 2016, as such a major attack could be a requirement for triggering the right to collective self-defence (Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty)[4].

Other issues that have surfaced through the global spread of COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine, such as energy and food security and economic security related to supply chains for rare minerals, semiconductors, etc., have not been neglected.[5] In addition, NATO has embarked on a long-term, strategic goal of addressing the impacts of climate change and large-scale infectious diseases, an approach that relates to the very foundations of human existence[6]. These are one important step towards the realisation of a multidimensional, 360-degree approach of deterrence and defence. Now the approach to 'North', 'South' and 'West' is likely to be the new focus at this Washington Summit.

Chart 2:Multidimensional, 360-degree approach of deterrence and defence

(1) Approach to the ‘North’

Since the end of the Cold War, the Arctic has been considered as part of the 'High North’, a region where geopolitical tensions are virtually non-existent. In recent years, however, the rapid melting of sea ice due to global warming has led to the rapid operationalisation of the Arctic in relation to securing natural resources, developing shipping routes and preserving undersea cables[7]. Already in 2019, in view of Russia's military build-up and increased military activities in the Arctic, NATO established Joint Force Command - Norfolk (JFC-NF) on the Atlantic coast of the United States, and it began vigilantly monitoring and maintaining command communications to the north. Moreover, with the new NATO membership of Finland and Sweden, seven of the eight Arctic countries have become NATO members (the remaining country is Russia). This means strengthening the defence posture in the region, including the Baltic Sea, has become a pressing issue. It is expected that the approach to the north will include the development of a warning and surveillance system from sea and air, the deployment of mobile deployment units and the strengthening of interoperability in extremely cold regions under a new structure of 32 member countries.

(2) Approach to the ‘South’

The Middle East, North Africa and the Sahel region, which NATO positions as the Southern Neighborhood, contain structural vulnerabilities and continue to have an unstable security situation that has resulted in many casualties. This instability has led to large-scale terrorist attacks, large numbers of internally displaced persons and illegal immigration, as well as increased Russian and Chinese influence with the hollowing out of the regional order[8]. In particular, the Sahel region of West Africa is in an ongoing negative security cycle of climate change impact, fragile social institutions, sanitary vulnerabilities, food insecurity and security-related chaos, which continues to fuel the humanitarian and development crisis. Since 2017, NATO has established a NATO Strategy Direction South - Hub (NSDS-Hub) to co-ordinate intelligence operations, counter-terrorism operations and capacity-building support, and is continuing efforts to strengthen information sharing and situational response coordination among the countries involved.

However, in view of the lack of improvement in the security and safety situation in the South, as well as concerns about the growing presence of the Global South, the multipolar nature of regional power and the risk of weaker Western industrialised countries[9], the alliance appears to have decided that a more in-depth response and involvement in the Southern Neighborhood is necessary. At the Washington Summit in July 2024, NATO will reach a new agreement on concrete action options for NATO's deterrence and defence of the South, based on the recommendations of the independent group of experts set up after the Vilnius Summit in 2023[10].

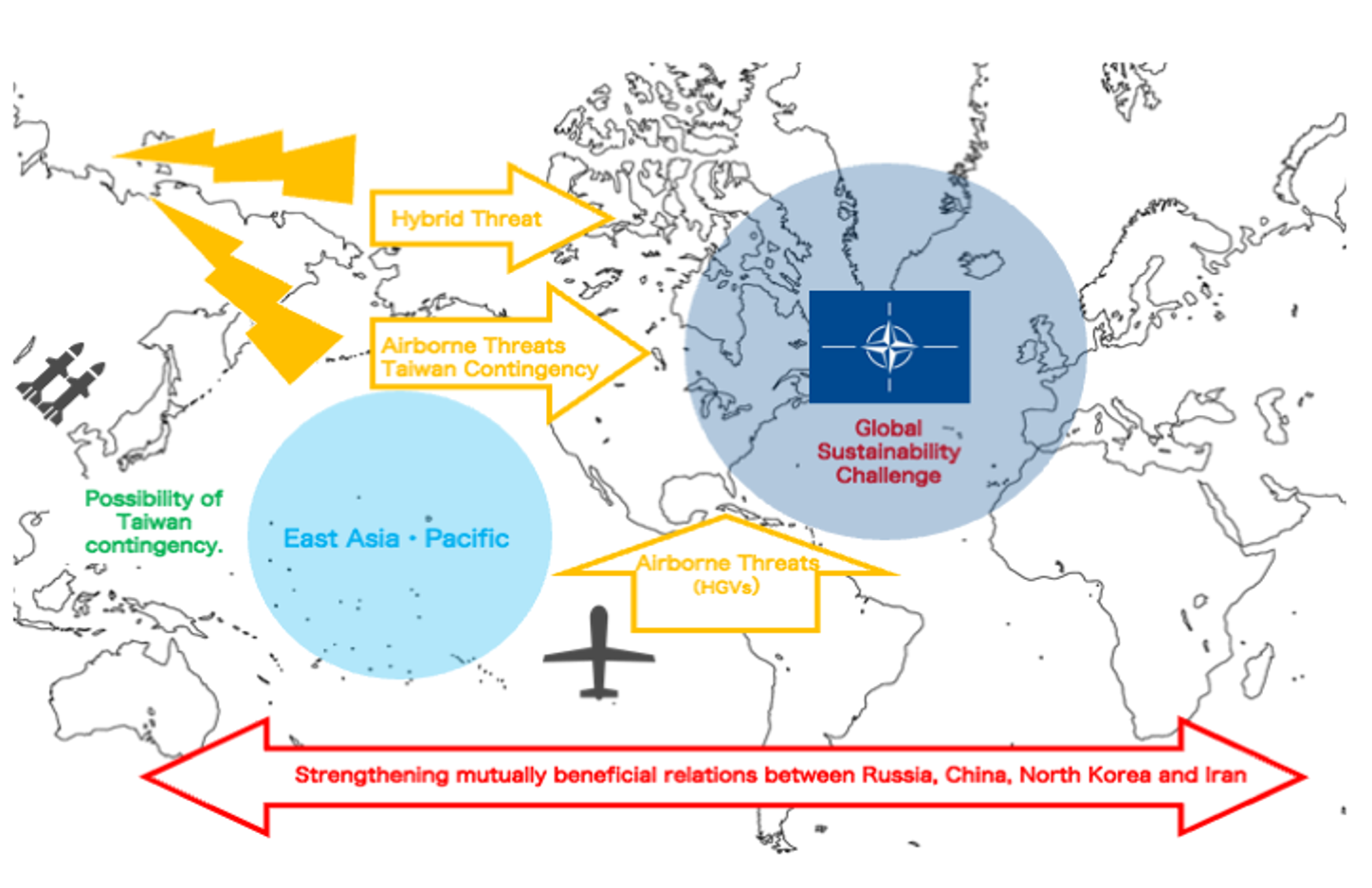

(3) Approach to the ‘West’

The West considers Russia, China, North Korea and Iran, which have been strengthening their global interlinkages[11], to be increasingly alarming as a group of authoritarian states that distort the rule of law and are willing to change the status quo by force. One example is the provision of economic and military assistance for Russia in the war in Ukraine. The US, which occupies the western flank of NATO, is the world's largest military power, and these authoritarian states are accelerating the development and deployment[12] of ballistic, cruise and hypersonic missiles and vehicles capable of carrying nuclear weapons that could attack the US mainland[13].

The US is deploying its own missile defence systems[14] to defend the North American region against these long-range airborne threats, and NATO also considers responding to threats from the West as a major task of the new Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD)[15].

Chatr 3:Threats and challenges from the western flank of NATO (North America)

However, the situation may be different in the case of a Taiwan contingency if, under China's Anti Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) strategy, US military forces deployed in the region suffer physical damage, and US allies such as Japan or the US mainland become targets of ballistic missiles or other attacks. It is expected that the North Atlantic Council (NAC), at the urging of the US as a member state (Article 4 consultations) and others, would identify these as a threat to the alliance as a whole and take steps to supplement US military forces in Europe after manoeuvring and deploying to the Indo-Pacific as NATO, and to engage indirectly to support the US in logistical matters[16].

In light of the growing likelihood of military coordination among and attempts to forcefully change the status quo by authoritarian states in East Asia and the Pacific, this westward approach will undoubtedly be an important deterrence and defence component of the 360-degree approach for NATO, and will accelerate the strengthening of NATO's partnership with Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand (Asia-Pacific Partners: AP4)[17].

Japan's option

In April 2024, the Japan-US Joint Leaders’ Statement declared that the bilateral alliance between the two countries would strengthen its character as a global partnership[18]. It suggests that the US-Japan alliance is being upgraded from a regional to a global security framework. This may be due to the fact that the challenges the two countries face are becoming more complex beyond their geographical scope in an increasingly interdependent world. Another factor is the growing need for security ties with the Euro-Atlantic region, as authoritarian countries such as Russia, China, North Korea and Iran increasingly coordinate and cooperate with each other. This is nothing less than the fact that the US-Japan alliance and NATO, which have never directly intersected before, are coming closer together as natural partners, and the areas of cooperation and collaboration are overlapping even more. At the Washington Summit in July, Japan will be expected to play a more active role in maintaining order through the rule of law in the East Asia and Pacific region, as well as maintaining and developing the US-Japan alliance, based on the National Security Strategy announced in 2022[19], in cooperation with NATO's approach to the West.

As threats and challenges become increasingly diverse and complex, the era of dealing with global security challenges in isolation is coming to an end. In order to complete and maintain the giant jigsaw puzzle of peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region, which has growing relations with Europe and the Atlantic region, it is important to carefully connect the pieces of the various players one by one. Additionally, partner countries within and outside the region that are expected to make multilayered contributions, not only the U.S. as an ally, and the active involvement of regional organisations, including NATO, are required. Japan, as one of the important pieces, must ensure that it fulfils the commitments expected of it globally and contribute worldwide to a stable and sustainable security environment in the Indo-Pacific region, while maintaining strong links with other pieces of the region.

(2024/05/24)

Notes

- 1 NATO, “Doorstep by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg ahead of the meetings of NATO Ministers of Foreign Affairs in Brussels,” April 3,2024.

- 2 NATO, “News: NATO’s defensive shield is strong'', says Chair of the NATO Military Committee,” February 28, 2022.

- 3 NATO, “Countering hybrid threats,” March 7, 2024.

- 4 NATO Allied Command Transformation, “The NATO Warfighting Capstone Concept,” June 5, 2023.

- 5 NATO, “Speech by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg at the Heritage Foundation followed by audience Q&A,” January 31, 2024.

- 6 NATO, “NATO’s Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) Defence Policy,” July 5, 2022.

- 7 NATO Allied Command Transformation, “The Future of the High North,” May 12, 2023.

- 8 Luis Simón and Pierre Morcos, “NATO and the South after Ukraine,” CSIS, May 9, 2022.

- 9 Lucas Resende Carvalho, “BRICS: The Global South Challenging the Status Quo,” globaleurope.eu, September 21, 2023.

- 10 NATO, “Secretary General receives final report from group of experts on NATO’s southern neighbourhood,” March 20, 2024.

- 11 Henry Foy, Felicia Schwartz, Demetri Sevastopulo and Claire Jones, “Yellen warns China of ‘significant consequences’ if its companies support Russia’s war in Ukraine,” Financial Times, April 6, 2024.

- 12 CSIS, “Missiles of China,” Missile Threat, April 12, 2021; Reuters, “North Korean missile can reach anywhere in the US, Japan says,” Deccan Herald, December 18, 2023.

- 13 Robert Soofer and Matthew Costlow, “US homeland missile defense: Room for expanded roles,” Atlantic Council, November 15, 2023.

- 14 Director Operational Test and Evaluation, “Missile Defense System (MDS),” February 01, 2024.

- 15 NATO, “NATO Integrated Air and Missile Defence,” June 13, 2023.

- 16 James Lee, “NATO and a Taiwan contingency,” NDC Outlook 02-2024, April 15, 2024.

- 17 MOFA, “NATO Asia-Pacific partners (AP4) Leaders’ Meeting,” June 29, 2022. This partnership is often referred to as IP4 (Indo-Pacific 4).Hae-Won Jun, “NATO and its Indo-Pacific Partners Choose Practice over Rhetoric in 2023,” RUSI, December 5, 2023.

- 18 MOFA, “Japan-U.S. Joint Leaders’ Statement: Global Partners for the Future,” April 10, 2024.

- 19 Cabinet Secretariat, “National Security Strategy of Japan,” December 16, 2022.