Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin reportedly tried to persuade Finland not to give up its neutrality, saying, “Now, when we look over the border towards Finland, we see a friend. If Finland joins NATO, we will see an enemy.[1]” On May 18, Finland and Sweden, two Nordic countries that had maintained a certain distance from NATO, officially submitted applications for membership in the military alliance. This was prompted by not only Russia’s growing military threat but also the need for collective defense against armed invasions and a joint response to nuclear threats, as competition for resources and security in the Arctic Ocean and High North[2] has intensified in recent years. This article examines the significance and implications of these two countries becoming members from the perspective of NATO’s Russia strategy and the maintenance of the alliance.

Russia’s Containment

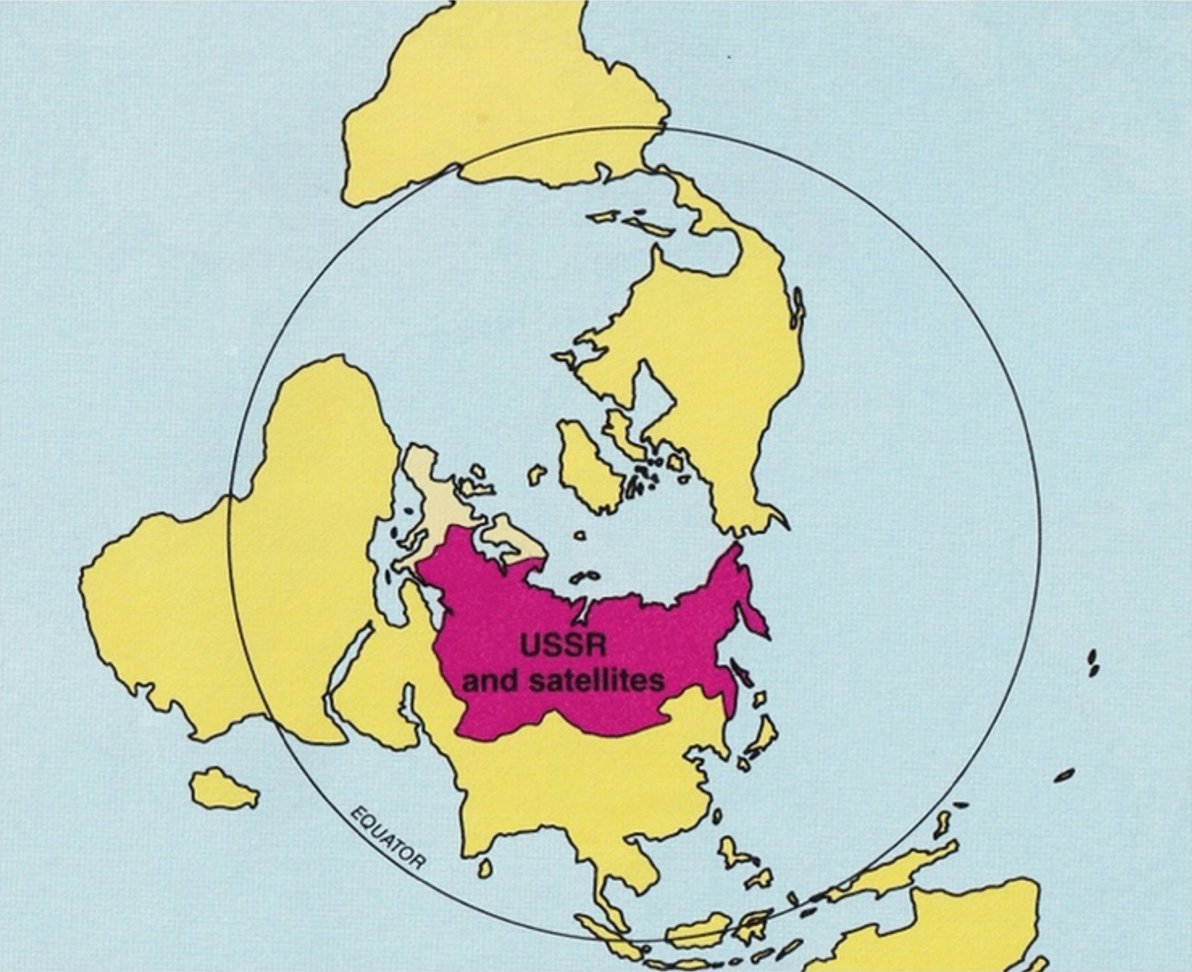

"The geopolitical value of Russia (former Soviet Union)as seen from the North Pole"

Because it is landlocked geographically, Russia has historically sought to expand externally in search of ice-free ports and to ensure access to the open sea—thought to be indispensable for its survival and growth[3]. For Russia, the Scandinavian Peninsula is a natural barrier to the open ocean, and the continued neutrality of Finland and Sweden was regarded as a geopolitical requirement for its survival (see Figure 1). With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, a downsized Russia lost its security buffer zone, while NATO began an eastward expansion under its Open Door Policy and extended the sphere of its influence. With the military invasion of Ukraine, Putin sought to stop NATO’s eastward expansion and regain the buffer zone Russia lost following the Cold War. But the move appears to have backfired, given the Finnish and Swedish decision to end its neutrality policy.

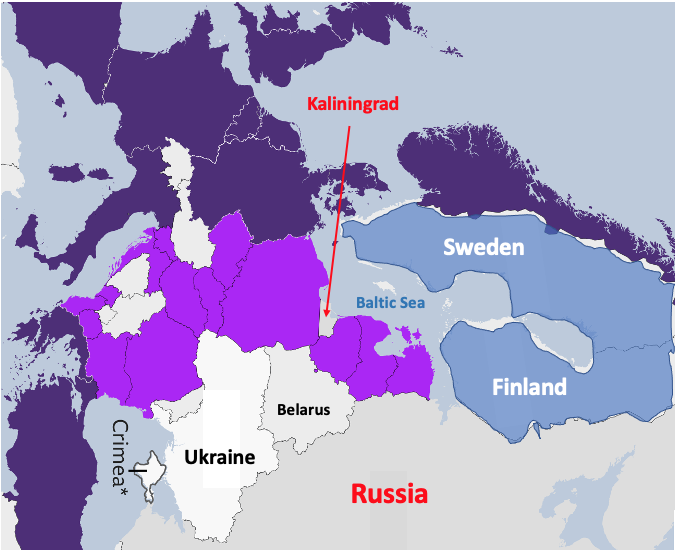

"Importance of the Baltic Sea as seen from Russia(Rotate original drawing 90 degrees)"

If Sweden and Finland were to join NATO, how would this impact on the security and military environment in Europe? For starters, the length of a direct land border between NATO and Russia would more than double from approximately 1,200 km at present to around 2,500 km.

Russia would have no choice but to beef up its military resources—at a significant economic cost—and enhance its surveillance posture for territorial security. Second, since almost all the countries bordering the Baltic Sea would become NATO members, Russia’s access to its enclave of Kaliningrad would become more difficult, and the activities of the Russian navy would be severely restricted (see Figure 2). In the skies over the Baltic states, NATO has been undertaking aerial security activities since March 2004. Its members regularly exchange fighters and other aircraft to guard against unidentified planes, including those from Russia. Should the Finnish and Swedish air force begin participating in these operations, NATO’s aerial security will become more diversified and have a significant impact on the operations of the Russian air force in the Baltic Sea.

In addition, Russia’s hybrid warfare capabilities in in the new operational areas of space, cyber, and cognitive domains will be greatly affected. Since Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Europe has taken systematic countermeasures against hybrid warfare, which combines traditional military operations with such nonmilitary means as cyber-attacks, deceptive and sabotage activities, and disinformation. Independent research institutes called Centers of Excellence (CoEs), for example, have been established one after another to deal quickly and effectively with threats from new domains, and they are advancing research into and developing concrete responses to hybrid threats[4]. Helsinki, Finland, is home to the European Center of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats (Hybrid CoE)[5], which offers expertise and training to counter hybrid threats, while Stockholm, Sweden, hosts the Center for Asymmetric Threat Studies (CATS)[6], which conducts research on hybrid warfare. Given their high technological literacy, Finland and Sweden can be expected to make an immediate contribution to research into the new domains. NATO emphasizes cooperation with the European Union and other international partners and will see its anti-hybrid warfighting capabilities improve should the two countries join, possibility even surpassing Russia in those domains.

New Military Challenges

In the future, NATO will be required to rebuild its existing military strategy and tactics as Russia redeploys its forces in response to the accession of Finland and Sweden. In 2020, NATO approved the Deterrence and Defense of the Euro-Atlantic Area (DDA) as a new military strategy. However, it will inevitably face new challenges in collectively defending northeast Europe should the two countries join. To meet those challenges, NATO must urgently “reset” its military posture[7].

"Russia's new Forward Defence Line may separate the Baltic States from NATO"

NATO would be obliged to expand the scope of collective self-defense (as stipulated in Article 5) and deal with new threats in the Arctic region (including the High North) and the Baltic Sea. The Arctic Council has hitherto secured the environmental protection and sustainable development of the region, but with the rapid melting of the Arctic sea ice due to global warming, the Arctic is becoming the focus of international cooperation and conflict over natural resources and sea route development. Russia is increasing its military presence and activities in the region[8], and NATO sees the Arctic as an emerging warfighting domain along with outer space and cyberspace. It will thus no doubt further accelerate its involvement in the region through fuller cooperation with Finland and Sweden.

In the Baltic Sea, meanwhile, concerning is growing over the strategic stability of Finland’s Åland Islands and Sweden’s Gotland Island[9], which have been remained demilitarized zones for historical reasons[10]. Moscow will likely take increasing military interest in these islands, though, as a strategic way of dividing NATO. Should the islands be taken by Russia and rearmed with long-range weapons, such as Iskander-M intermediate-range nuclear missiles, NATO countries will be confronted with a direct military threat a few dozen kilometers away—just like the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad.

In addition, if Russia or ally Belarus moves to occupy a critical strategic corridor of NATO defense called the Suwałki Gap that runs for 104 km along the Polish-Lithuania border, a long forward line of defense linking Belarus, the Suwałki Gap, Kaliningrad, and the occupied islands of the Baltic Sea would emerge, putting the three Baltic NATO members in danger of being isolated (see Figure 3).

"Submarine cable laying situation around the Baltic Sea"

There are also growing concerns about the safety of undersea cables[11], which currently carry 99% of all digital data worldwide. Åland and Gotland are key cable relay stations in the Baltic Sea. Should Russia invade the islands and destroy the cable facilities, this could seriously impact on communication among NATO members, especially for the Baltic states. This is tantamount to a nonmilitary attack by Russia (see Figure 4) on the cyberspace of the Baltic states. This would not only physically disrupt operations, supplies, and communication within NATO but also lead to the loss of digital information sharing and command and control functions.

In July 2019, NATO established Joint Force Command - Norfolk (JFC Norfolk) to strengthen its operational posture across the Atlantic and to strengthen cross-Atlantic ties among allies and partners. The mission of JFC Norfolk includes the maintenance of submarine cables deployed at the bottom of the North Atlantic and other oceans[12].

Should the Finnish and Swedish navies come under the command of JFC Norfolk, this will further enhance interoperability in both real and virtual domains. And the evolution of these capabilities should create the foundation for deterring and defending against Russian military aggressions in the Arctic and Baltic Sea.

Conclusion

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has made it clear that Finland and Sweden are strong, mature democracies and important partners of NATO and that the process for their accession is expected to progress smoothly [13]. The process requires accession negotiations and the ratification of the Accession Protocol by all member countries. Therefore, a certain amount of time will be required before both countries can become members[14]. Turkey, moreover, has indicated it is opposed to their accession for political reasons[15]. Conflict and tensions among alliance members are nothing new, however, as seen during the Suez Crisis in the 1950s and the Iraq War in 2003, and NATO has both experience and confidence in overcoming such crises. Over the years, NATO has developed an organizational culture that accepts diversity and differences of opinion[16]. As long as members agree on the fundament importance of maintaining a US-Europe alliance, NATO—even after Finland and Sweden join—will likely be able to adapt to changing circumstances and continue to evolve as a political and military alliance that fulfills its inherent responsibilities.

Translated from an article originally published on the Japanese IINA website on June 2.

(2022/06/24)

Notes

- 1 John Ringer and Meghna Chakrabarti, “The risks and rationale of expanding NATO,” Wbur on Point, April 28, 2022.

- 2 The “High North” refers to the “land and sea area from southern Helgerand in the south to the Greenland Sea in the west and the Pechora Sea in the east (southeast corner of the Barents Sea).” See “The Norwegian Government’s Arctic Policy: People, opportunities and Norwegian interests in the Arctic – Abstract,” January 26, 2021.

- 3 “Warm-water ports a factor in Russian foreign policy calculations,” The Federal, February 26, 2022.

- 4 NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, “EU Commission President and NATO Secretary General visit NATO StratCom COE,” November 28, 2021.

- 5 Axel Hagelstam, “Cooperating to counter hybrid threats,“ NATO Review, November 23, 2018.

- 6 Josefin Svensson, “Spotlight on hybrid warfare,” Swedish Defence University, March 4, 2022.

- 7 NATO, “News: NATO Secretary General to Allied Defence Chiefs: ‘Reset’ our posture to reflect new reality in Europe,” May 19, 2022.

- 8 Thomas Graham and Amy Myers Jaffe, “There Is No Scramble for the Arctic: Climate Change Demands Cooperation, Not Competition, in the Far North,” Foreign Affairs, July 27 2020.

- 9 The Åland Islands are demilitarized by international law. Gotland was also demilitarized in 2004 but was re-armed in 2017.

- 10 Eoin Micheál McNamara, “Securing the Nordic-Baltic region,” NATO Review, March 17,2016.

- 11 Kurt Kohlstedt, “Underwater Cloud: Inside the Cables Carrying 99% of Transoceanic Data Traffic,” 99% Invisible, June 30, 2017.

- 12 Thomas Nilsen, “As Finland and Sweden join NATO, Norfolk command beefs up readiness in alliance’s northern flank,” The Barents Observer, May 15, 2022.

- 13 NATO, “Press point with NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg and the President of the European Parliament, Roberta Metsola,” April 28, 2022.

- 14 NATO, “Topics: Enlargement and Article 10,” May 18, 2022.

- 15 Anna Kaplan, “Turkey’s Erdogan Told Allies It Will Say ‘No’ To Finland And Sweden’s NATO Bids, In His Most Definitive Statement Yet,” Forbes, May 19, 2022.

- 16 NATO, “Doorstep statement by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg prior to the meetings of NATO Defence Ministers,” June 7, 2018.