The February 2018 declaration of a state of emergency in the Maldives triggered a spike in naval activity in the Indian Ocean. India was reportedly preparing to send troops to restore political stability to the island nation, and 11 Chinese naval vessels entered the Indian Ocean at around the same time.[1] China already had 3 ships carrying out antipiracy operations off the coast of Somalia, meaning that 14 PLA Navy vessels were deployed in the Indian Ocean. The sizable Chinese presence prompted India to stage large-scale exercises in the Indian Ocean and to send a fleet to head off the Chinese incursion, after which the Chinese warships retreated.

Why are India and China stepping up their naval maneuvers in the Indian Ocean? What are the factors behind rising tensions in the region? And how are these developments significant for Japan? I will address these questions below.

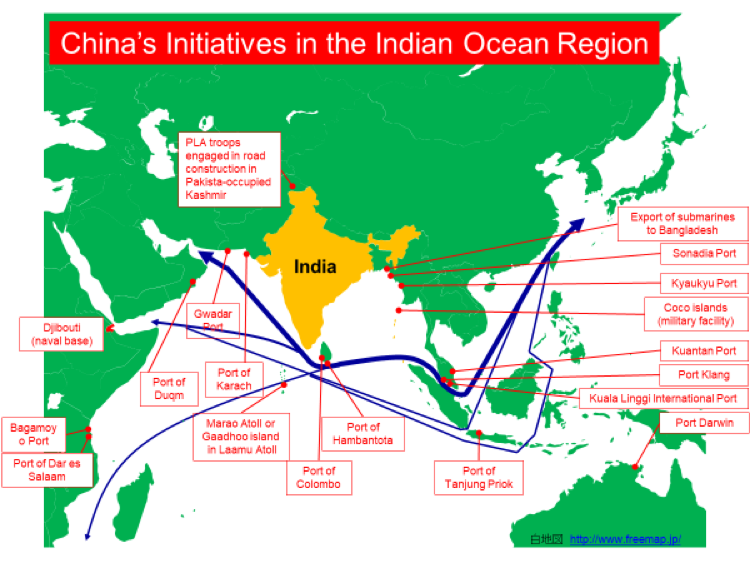

China’s Growing Naval Presence

The Indian Navy has been prodded into action to counter what is known as Beijing’s “string of pearls” strategy, launched after the turn of the millennium to expand its geopolitical influence by building ports and other civilian maritime infrastructure along the Indian Ocean periphery.[2] China has also established a military surveillance facility on Myanmar’s Coco Island near the Malacca Strait, helping to facilitate the entry of Chinese naval ships into the Indian Ocean region. China’s presence grew steadily following its participation in antipiracy operations off the coast of Somalia in 2008. In a news conference in December 2017, the Indian chief of the naval staff noted that eight ships of the Chinese PLA Navy were regularly deployed in the Indian Ocean, including nuclear-powered submarines.[3] China has sold 10 submarines to India’s closest neighbors—8 to Pakistan and 2 to Bangladesh—and has established a naval base in Djibouti. It would not be inconceivable for Beijing to dispatch an aircraft carrier strike group to the region in the not-too-distant future.

India’s Concerns

China’s push into the Indian Ocean raises the specter of an Indian ballistic missile submarine being attacked by a Chinese submarine or the Indian Ocean sea lines of communication being blocked by Chinese warships during a contingency. But there are ramifications even during peacetime, as Beijing’s heightened presence may prompt some countries that had been friendly toward New Delhi to shift allegiances. In a sense, China may be practicing what ancient military strategist Sun Tzu held up as being the supreme art of war: to subdue the enemy without fighting. India, consequently, has felt the need to further raise its profile.

Figure 1. Chinese Initiatives in the Indian Ocean Region

Source: Compiled by the author.

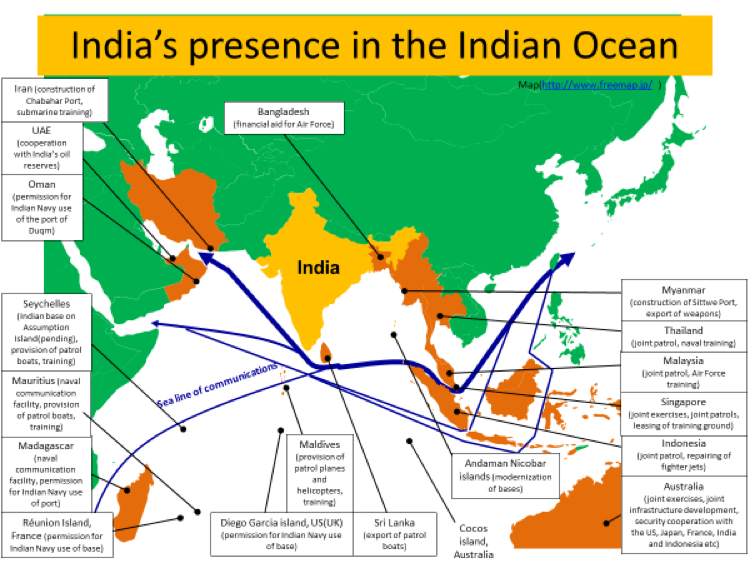

India’s Countermeasures

How is India enhancing its regional presence in the face of Chinese advances? New Delhi has thus employed two major approaches.

(1) Military Presence

The first is to display military strength. India has been steadily taking steps to expand the scope of its activity in the Indian Ocean since 2001. It has modernized its bases on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, which are near the Malacca Strait, established naval surveillance facilities in Madagascar and Mauritius, and launched a military satellite to enable communication even while far offshore. It began making annual tours of countries around the Indian Ocean with small divisions of around four ships, and the visits gained additional momentum after Narendra Modi became prime minister in 2014. During the first year of the Modi administration, Indian naval ships visited over 50 countries, including friendly port calls by an aircraft carrier to the Maldives and Sri Lanka. In 2016, the Indian Navy hosted an international fleet review, in which over 100 warships from 50 countries participated. In October 2017, it launched large-scale “mission-based deployments” for the seven missions in which the Indian Navy is currently engaged.[4] It entails dispatching ships for around three months each and having them make port calls in various countries to enhance India’s naval presence. And in May 2018, India decided to station fighter jets in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands to be prepared for the entry of Chinese carrier groups into the region.

These maneuvers require access rights to ports in each country. In 2016, India secured such rights to Diego Garcia from the United States,[5] to the port of Duqm from Oman, and to Réunion Island from France (see Figure 2). And in 2018, it reportedly reached agreement with the government of Seychelles to build a base on Assumption Island.

(2) Capacity Building

India’s second approach to enhancing its military presence is to provide capacity building assistance for countries in the region. Such assistance may be provided in either India or the recipient country or consist largely of financial support.

The first type of assistance includes accepting foreign students to undergo training in India, repairing equipment, or loaning tracts of land to conduct military drills. Malaysian fighter jets, for instance, were brought to India for servicing, and Singapore has a long-term arrangement for the use of India’s training grounds.

Assistance provided in the recipient country usually consists of dispatching instructors, sometimes together with the provision or export of equipment. For example, Indian military personnel have been stationed in the Maldives, Seychelles, and Mauritius to train local troops in the use of the patrol planes, helicopters, and boats that were supplied to those countries.

Financial assistance has increased conspicuously since Modi became prime minister. In April 2017, he agreed to furnish $500 million in aid for the Bangladesh Air Force, expected to be used to purchase repair parts for fighter jets and to conduct studies in the selection of next-generation fighters.[6] What does India stand to gain by shouldering the bill for Bangladeshi plane parts? First, India would acquire a firsthand understanding of the state of Bangladesh’s military aircraft. Should Bangladesh become dependent on India for the purchase of parts, moreover, it may even be possible to choke off supplies and keep the fighters grounded. Bigger yet, India can also leverage the aid to prevent its neighbor from purchasing jets from China, which could enable the PLA to gain a permanent foothold at an Bangladeshi air base.

Figure 2. India’s Initiatives in the Indian Ocean Region

Source: Compiled by the author.

Significance for Japan

What does the escalation of naval activity in the Indian Ocean mean for Japan? A greater Chinese presence in the region might necessitate the deployment of Japanese ships to defend the Indian Ocean, which is a vital sea lane for Japan. In fact, Japan has been dispatching naval vessels to the region for over 16 years since 2001 precisely to defend shipments of oil from the Middle East.

There are limits to the number of ships Japan can actually deploy in the Indian Ocean, however, and even the US Navy is overstretched. By contrast, there has been a rapid expansion and modernization of the PLA Navy; whereas the United States built and commissioned 15 new submarines between 2000 and 2016, China has built and deployed 44 new subs over the same span. The Japan-US security alliance is focused on the East and South China Seas, and does not have the capacity to significantly boost its presence in the Indian Ocean.

For this reason, it is in the interest of both Tokyo and Washington for New Delhi to undertake the bulk of the security task in the Indian Ocean. The joint statement issued following the September 2017 visit to India by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe read, “The two Prime Ministers . . . noted the ongoing close cooperation between the Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force (JMSDF) and the Indian Navy in various specialised areas of mutual interest, including anti-submarine aspects.”[7] Some security experts have speculated that India is building an “undersea wall” of sensors along the coastline of the Bay of Bengal, stretching as far as Hainan Island, to detect Chinese submarine activity.[8] Such initiatives help to bolster Japan’s national security, so the Japanese government would do well to lend its full and active support to New Delhi, such as by sharing shipbuilding expertise and providing ships and aircraft to not only India but to other friendly countries in the region.[9]

Original Japanese article was posted on July 10, 2018

Notes

- 1“Chinese warships enter East Indian Ocean amid Maldives tensions”, Reuters, February 20, 2018

(https://www.reuters.com/article/us-maldives-politics-china/chinese-warships-enter-east-indian-ocean-amid-maldives-tensions-idUSKCN1G40V9 ) - 2China has developed ports around India in Gwadar, Pakistan; Hambantota, Sri Lanka; Chittagong, Bangladesh; and Kyaukpyu, Myanmar. When joined together, the ports appear to be a “string of pearls” around the neck of the Indian subcontinent and are feared by New Delhi to be part of a Chinese encirclement strategy. These ports are all currently commercial facilities and used for civilian purposes only. In the near future, though, they may serve as resupply and recreation stations for Chinese naval vessels and their crew, enabling the PLA Navy to extend its reach into the Indian Ocean.

- 3“India Begins Project To Build 6 Nuclear-Powered Submarines,” NDTV, 1 December 2017.

- 4The seven missions enable the Indian Navy to exert its presence and are deployed, to the east, to the (1) Malacca Strait, (2) Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and (3) northern Bay of Bengal and northern Andaman Sea, and, to the west, to the (4) Strait of Hormuz, (5) coast of Somalia, (6) Sri Lanka and Maldives, and (7) Mauritius, Seychelles, and Madagascar.

- 5Diego Garcia is technically British territory but has been loaned to and is used as a base by the United States since the British Navy retreated from territories east of the Suez.

- 6“India commits $500 million credit for Bangladesh military”, The New Indian Express, 8 April 2017.

- 7“Japan-India Joint Statement: Toward a Free, Open and Prosperous Indo-Pacific,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, September 14, 2017.

- 8Abhijit Singh, “India’s ‘Undersea Wall’ in the Eastern Indian Ocean,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, 14 June, 2016.

- 9In addition to exporting two US-2 air-sea rescue amphibious aircraft to India, Japan is considering providing two patrol boats and a used P-3C maritime surveillance aircraft to Sri Lanka. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Japan-Sri Lanka Summit Meeting.” K. Balachandran, “Japan may help SL buy P-3C maritime surveillance aircraft”, Daily Mirror, 21 April 2017(http://www.dailymirror.lk/article/Japan-may-help-SL-buy-P-C-maritime-surveillance-aircraft-127555.html )