Countering China’s “String of Pearls” Strategy

On a fact-finding trip to the Middle East in summer 2016, I was struck by China’s advances and presence in the region. I found countless Chinese people in each country I visited, many of whom were engaged in generously financing infrastructure or other facilities. These overtures had succeeded in winning Beijing new friends among the leaders of these countries, notably Oman.

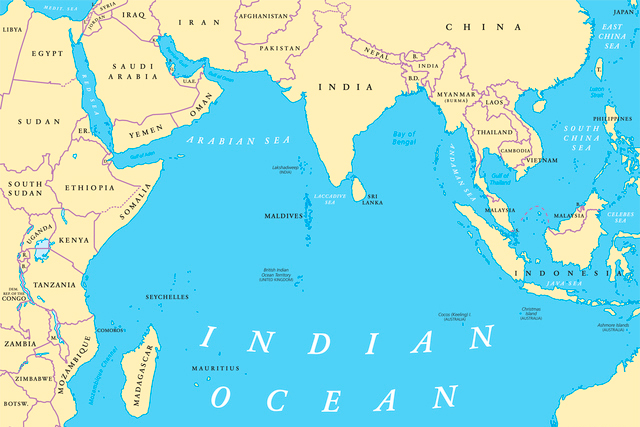

Over the past several years, China has established a military base in Djibouti and obtained a 99-year lease for the use of a Sri Lankan port. Colombo is in dire fiscal straits, having to use most of its revenue to finance its debt, and it is considering leasing or selling off additional nationally held assets, such as airports.[1]

Until around the end of the previous century, Japan’s official development assistance and investments by Japanese companies played a major role in the region’s economic development. Japan’s once prominent presence has waned, however, as China has made forceful advances into countries around the world on the strength of its high-growth economy.

Must Japan just sit and watch as China’s grip on Asia tightens, winning one country after another to its Belt-Road Initiative with its promise of big economic returns? Under the circumstances, the most effective course Japan can take, judging from my personal experience, would be to provide assistance through initiatives in the nongovernmental sector, once more winning over friends among countries in the region.

In September 2016, I proposed advancing closer cooperation with India in South and Western Asia in order to balance China’s “string of pearls” strategy.[2] It is in Japan’s interest to continue partnering with countries that are resisting China’s expanding influence, particularly India, and also with countries like Afghanistan that are in need of development assistance. But this is not enough to stop countries like Sri Lanka that are facing severe fiscal difficulties from turning for help from Beijing. For Japan to remain viable in the region, we must extend a helping hand by offering solutions to the biggest problems these countries are facing.

Given the limited resources of the Japanese government and private companies, a potentially highly effective approach would be closer civil-sector cooperation in the field of disaster management.

Providing Help When It Is Most Needed

Earthquakes, tsunamis, typhoons, floods, landslides, and other natural disasters can strike any country and cause great damage. It is the government’s responsibility to act quickly in the wake of such emergencies, but the ability to respond effectively varies from country to county. In many developing countries, NGOs and local community groups must often take action to make up for any lapses in the government response. It is often the case that where governments are not fully capable of taking adequate action, there is a well-developed civil sector ready to fill the gap.[3]

The Philippine government, for example, adopted a policy of forcibly moving many poor residents into new homes following a typhoon that devastated their villages. But the task of meeting the employment, healthcare, and education needs of these uprooted residents was largely met by civil society organizations.[4] The disaster response center was financed by major companies, moreover, and operated by an NGO supported by those companies.[5]

In the Philippines, NGOs and private businesses regularly play a major role in bringing relief to disaster-affected residents, and similar arrangements can be found in other Asian countries. The equipment, facilities, and training in these countries are often far from adequate, however, and help from Japan in these areas would be highly appreciated and would have great value.

It is feasible for the government to provide assistance in the form of ODA, particularly equipment and facilities offered through the technical cooperation projects administered by the Japan International Cooperation Agency. But given that the groups most in need of these goods are NGOs and other members of civil society providing disaster relief on the ground, coordination could be facilitated if assistance came from their counterparts in Japan.

In many Asian countries, NGOs are playing a central role in coordinating the disaster-response activities of the civil sector, private businesses, and the government, and this track record has engendered trust among the parties engaged. If Japanese NGOs can partner with the groups that are active locally, this can help to foster trust not only in Japan’s civil society but also in the country as a whole.

The Countries Requiring Disaster Relief

It so happens that the countries requiring the greatest assistance in the area of disaster management are those with the closest ties to China, namely, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines. The first three countries are counted as being part of China’s “string of pearls” strategy, while the latter three have territorial disputes with Beijing in the South China Sea.

An internationally active Japanese NGO already exists that is familiar with natural disasters and that can fully serve as a counterpart to local groups in these countries. The Asia Pacific Alliance for Disaster Management (A-PAD), of which I serve as senior adviser, has partnered with national platforms for disaster relief in Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and the Philippines. It remains to be seen whether similar partnerships can be forged with groups in Myanmar and Vietnam, but this is nonetheless an important example of Japan’s civil society working with its counterparts in Asia in the field of disaster management.

Over the past decade, many Japanese NGOs engaged in international cooperation have expanded the scale and quality of their operations, some seeing a fivefold jump in their budget. It is to be hoped that these groups can contribute to enhancing the disaster-management capabilities of many more Asian countries. At the same time, one also hopes that the Japanese government will significantly bolster its support for NGOs, outlays for which currently makes up just 2% of the total ODA budget.[6]

Original Japanese article was posted on May 23, 2018

Notes

- 1“Suri Ranka saimu no daisho,” Nihon Keizai Shimbun, May 2, 2018.

- 2Nobutaka Miyahara, “Afuganisutan, Iran ni okeru Nichi-In kyoryoku,” Tokyo Foundation website, September 5, 2016. The “string of pearls” strategy seeks to secure China’s economic and military interests by building ports along the South China Sea and Indian Ocean periphery from Hong Kong to Port Sudan.

- 3Presentation by Bunkyo University professor Kaoru Hayashi at the February 27, 2016, symposium organized by the International Society of Volunteer Studies (held at the Mii Campus of Kurume University).

- 4Presentation by Glenn Baticados, associate professor at the University of the Philippines, Los Baños, at the February 27, 2016, symposium organized by the International Society of Volunteer Studies (held at the Mii Campus of Kurume University).

- 5As briefed to the author by members of the Philippine Disaster Resilience Foundation (PDRF), March 23, 2018, in Manila, Philippines.

- 6As compiled from data appearing in OECD, “Aid for CSOs: Statistics based on DAC members’ reporting to the Creditor Reporting System database,” December 2015, https://www.oecd.org/dac/peer-reviews/Aid%20for%20CSOs%20in%202013%20_%20Dec%202015.pdf.