South Korea’s Defense Spending Breaks the 50-Trillion-Won Threshold

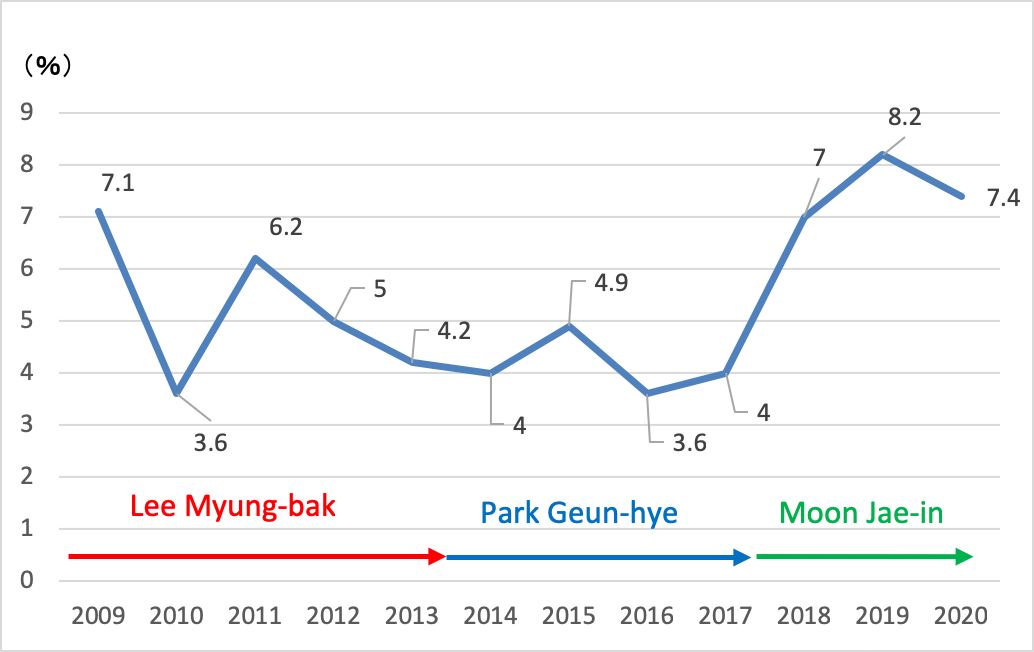

The National Assembly of the Republic of Korea (ROK) approved the government’s budget last December, meaning that from January, total spending on national defense for fiscal 2020 will be 50.1527 trillion won ($42.2 billion[1]), up 7.4% from the previous year. As I wrote in October 2018[2], for President Moon Jae-in to realize his “Defense Reform 2.0” program, one of his policy priorities, the government will request an average increase of 7.5% every year until 2023.

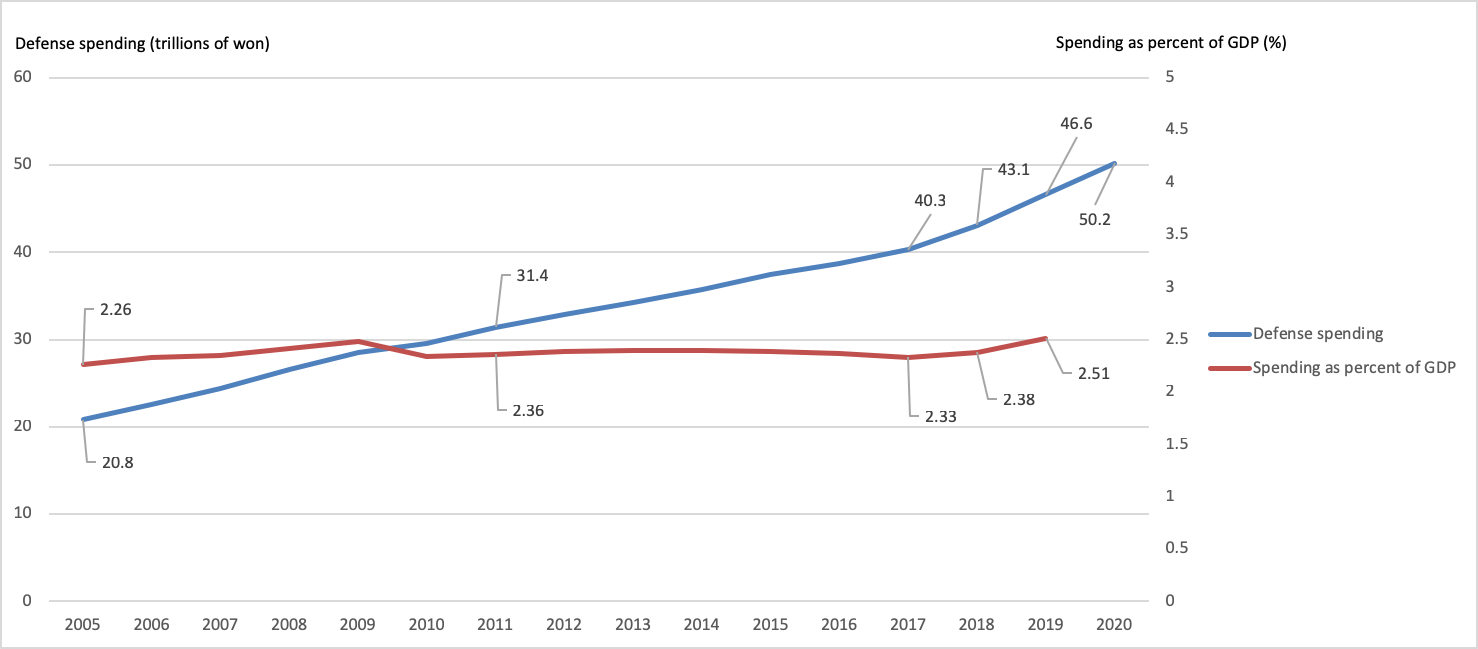

South Korea’s defense spending has hit significant benchmarks every six years, jumping from about 20 trillion won in 2005 to roughly 30 trillion won in 2011, and then to about 40 trillion won in 2017. The Moon administration will hit the next 10-trillion-won marker in just three years[3].

Rate of Increase in South Korea’s Defense Spending (2009-2020)[4]

Changes in South Korea’s Defense Spending and Defense Spending as a Percent of GDP (2005-2020)[5]

South Korea had the world’s tenth largest defense budget in 2018, according to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), just behind that of Japan[6]. Its defense spending is more than 2% of GDP, a threshold many NATO members fail to meet. That means that South Korea is paying not only host-nation costs for the U.S. military presence there, but it is also buying large amounts of U.S.-made military equipment. The Trump administration has nevertheless requested a significant increase in the ROK’s share of host-nation costs, provoking a great deal of dissatisfaction.[7]

A National Defense that None Can Underestimate

On January 21, the South Korean Defense Ministry delivered its start-of-the-year report[8] to President Moon. “To establish a sound national defense posture, we will create a defense that none can underestimate through an appropriate defense buildup in the age of 50-trillion-won defense budgets,” said Defense Minister Jeong Kyeong-doo in the report[9].

For the purpose of “securing military response capability against threats from all directions,” the details of that buildup include 6.2156 trillion won for the following equipment for “securing response capability to nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction”: F-35A aircraft, military surveillance satellites, tactical surface-to-surface guided weaponry, JangBogo III submarines, Gwanggaeto-the-Great-class destroyers, radar for early warning of ballistic missiles, ship-to-air guided missiles, and improving the performance of Patriot Missiles.

The budget also contains 1.9721 trillion won for “continuing reinforcement of South Korea’s core defense capabilities to lead in coordinated defense (with the U.S.),” which includes 230 caliber multiple launch rockets, tactical communications systems and so on[10].

An 11% increase in “military reinforcement expenditures” in the budget contrasts with the decreasing “military management expenses” that come with the gradual decrease in army manpower.

Judging by the contents of the Defense Ministry report and this fiscal year’s budget, it is clear that there is no change in South Korea’s drive to establish verified response capability to North Korea’s ongoing development of nuclear and ballistic missiles. It is also clear from its push to “oppose threats from all directions” that is looking not only to the north, but also to other countries in the region[11].

The budget is also evidence of the Moon administration’s push to gain operational wartime control from the U.S. military before the end of Moon’s term.

This kind of active military spending, and the policy of continuous defense reinforcement that relies on it, do not create conflict between the ruling and opposition parties in the ROK. However, People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy (PSPD), an influential left-leaning civic group that is a strong supporter of the Moon administration, made clear its opposition to greater defense spending, saying that “this large-scale military spending moves the North-South peace agreement backward, endangers the peace process on the Korean Peninsula and should be stopped[12].” The group produced some of the central figures of the administration, such as former Justice Minister Cho Kuk, so its opposition is notable.

A “Poison Needle Strategy” for Neighboring Countries (i.e., Japan and China)

With the trends of growing defense spending and military buildup becoming more clear, on September 22 last year an article in the JoongAng Ilbo introduced the concept of the “poison needle strategy.” In this scenario, the South Korean military would strike Japan and China’s cores (i.e., command centers and important facilities) using ballistic missiles and submarine-launched ballistic missiles. That means the South Korean military “needs the capability to deter the possibility of future threats from neighboring Japan and China.”

The article also cited the thinking of a South Korean military official who said, “If South Korea and Japan end up in a military confrontation, the U.S. would likely remain neutral.” The concept borders on the unbelievable.[13]

The contents of the article have not been confirmed, but in a September 2017 meeting between Moon and Trump, Moon reportedly received Trump’s approval to obtain nuclear submarines[14]. In a report to the National Assembly last October, the Navy Chief of Staff acknowledged that the navy is operating a task force related to introducing nuclear submarines [15]. However, for South Korea to acquire nuclear propulsion submarines, the nuclear cooperation agreement with the U.S. would need to be amended, a high hurdle according to some.

Moreover, if submarine launched ballistic missiles are fitted with conventional warheads, these “poison needles” will not deliver a lethal blow to their intended targets. That means they would need nuclear warheads, which would raise a great deal of suspicion in China and Japan. As a result, even if this strategy truly exists, the likelihood that it will be implemented is not high.

There is no guarantee that South Korea, caught up in the confrontation between the U.S. and China, will not pursue a strategy that acts against Japan’s national interest. On the other hand, South Korea remains an important neighbor that shares the values of freedom and democracy, as well as an important geopolitical buffer. Politically, the root causes of the deterioration in Japan-South Korea relations are the issue of reparations for wartime labor by Korean workers, and the ongoing attitude that “the ball is in South Korea’s court.”

In the realm of security, Japan needs to develop a new vision for a forward-looking Japan-ROK security relationship that contributes to stability in northeast Asia. At the same time, it must monitor South Korea’s military development and ensure that it does not act based on miscalculation and it remains aligned with Japan and the U.S.

As a neighboring country that is developing more military power, Japan- U.S.- South Korea cooperation is a framework not only for deterring North Korean aggression, but also ensuring that South Korea does not become a potential threat to Japan by focusing on an extreme vision of national defense. Japan should realize the importance of this framework.

(2020/03/12)

Footnotes:

- 1 Using current conversion rate on March 11. The South Korean fiscal year is the same as the calendar year.

- 2 https://www.spf.org/iina/articles/ito-korea-defref2.html(Japanese).

- 3 “[2020 Budget] Defense Spending Surpasses 50 Trillion Won… Salaries to 540,000 Won,” Yonhap News Agency, August 29, 2019(Korean).

- 4 Made using budget data from the Ministry of National Defense homepage(Korean).

- 5 Ibid.

- 6 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute homepage.

- 7 As an example of media reaction: “Excessive demands,” Korea JoongAng Daily, October 31, 2019.As an example of government reaction: Jeong Kyeong-doo, “South Korea’s defense minister on a mutually reinforceable, future-oriented ‘Great ROK-US Alliance,’” Defense News, December 2, 2019.

- 8 These are important reports submitted by every ministry and agency to the president that cover the last year’s activities and next year’s plans.

- 9 “Kanbeigodoenshu wa naiyochosei shite jisshi kokubobu ga daitoryo ni gyomuhokoku,” (Contents of U.S.-South Korea joint maneuvers being coordinated Defense Ministry reports to President), Yonhap News Agency, January 21, 2020 (Japanese).

- 10 Republic of Korea Ministry of National Defense homepage (Korean).

- 11 “Mun Jein Seiken no jishukokubo shinbaajon … pyonyan dake? Pekin Tokyo nimo kenseikyu (1)” (Moon administration’s new version of autonomous national defense … just Pyongyang? Also checking Beijing and Tokyo), Korea JoongAng Daily, September 22, 2019 (Japanese).

- 12 People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy, “PSPD view on 2020 national defense plan,” November 5, 2019 (Korean).

- 13 “Mun Jein Seiken no jishukokubo shinbaajon … pyonyan dake? Pekin Tokyo nimo kenseikyu (1)” (Moon administration’s new version of autonomous national defense … just Pyongyang? Also checking Beijing and Tokyo), Korea JoongAng Daily, September 22, 2019 (Japanese).

- 14 Ibid.

- 15 “’Working to get nuclear submarines, useful in tracking and destroying North’s SLBM,’ says Navy, Yonhap News Agency, October 10, 2019 (Korean).