Review of “Defining U.S. Indian Ocean Strategy”

Contents

In spring 2012, Michael J. Green (Senior Advisor and Japan Chair at Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. and Associate Professor at Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University) and Andrew Shearer (Director of Studies and a Senior Research Fellow at the Lowy Institute for International Policy in Australia) published a 15-page article titled “Defining U.S. Indian Ocean Strategy” in The Washington Quarterly published by Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

The authors have analyzed and defined the Indian Ocean strategy of the U.S. as there is, now, a growing awareness of the Indian Ocean in the US, Australia and Japan. In this article, there are three focuses of US interest as listed below. Firstly, the Indian Ocean is important to maintain as a secure highway for international commerce. Secondly, there are strategic choke points of the Indian Ocean highway in the Strait of Holms on one end and the Strait of Malacca and South China Sea on the other. Considering there is crisis with Iran and China, these areas are of more immediate concern for the US. Thirdly, the Indian Ocean is likely to remain the main arena of Sino-Indian Competition in the long run or at least in near future.

The authors have also analyzed how these three US interests should be dealt with while at the same time analyzing their seriousness. In this review, I will first summarize the main points of the article, followed by expressing my opinion about why Japan and U.S. are presently interested in the Indian Ocean.

I. Summary of the main points of the article

The Indian Ocean has emerged as a major center of geostrategic interest in the past few years. U.S. and key U.S. allies have also mentioned the Indian Ocean in their official documents such as The Pentagon’s 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), Australia’s 2009 Defence White Paper and Japan’s 2011 National Defense Policy Guidelines.

Such official focus on the Indian Ocean, by way of these documents, has been fueled by Robert Kaplan’s 2010 book Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power and documents written in the Naval War College, the American Enterprise Institute, the Lowy Institute (Australia), and the Ocean Policy Research Foundation (Japan) etc. All of these strategic researches have made a long list of security issues.

According to the view from U.S., the Indian Ocean region is not a region that resembles the 19th-century strategic vulnerability of the Caribbean under threat from Europe or the 20th-century Western Pacific from Japan. This is because India is likely to be a “net exporter of security” in the Indian Ocean region in the future. If so, what vital U.S. interests really are at stake today? What strategy is required to protect and advance those interests?

1. U.S. Interests

While deliberating upon the focal points of U.S. strategy, to maintain the Indian Ocean as a secure highway for international commerce is the most important. To maintain freedom of navigation through the strategic chokepoints of the Indian Ocean highway – the Strait of Hormuz, the Strait of Malacca and the South China Sea, around southern Africa and the Mozambique Channel – is second. Thirdly, the Indian Ocean region could become an arena for great power strategic competition between India and China.

(1) Thinking through Sino-Indian Competition

It is important to assess these trends cautiously and carefully. Even if China develops effective power-projection forces (20 or 30 years later) including an effective carrier-borne strike forces and military support facilities in the Indian Ocean, this would still operate at some disadvantage. Long distances from ports in southern China would make for their supply lines vulnerable around the Strait of Malacca and other chokepoints. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) would face challenges very similar to the situation the imperial Japanese navy faced in the Indian Ocean during 1942 ~ 1943 when they could not dominate in the region.

However, there is another example from history that suggests being cautious. Though the Soviets never had the ability to dominate the Indian Ocean region, but one cannot deny the possibility of them transferring what are now called anti-access/area denial (A2AD) capabilities to the Indian Ocean. This possibility could have been a serious threat during Cold War. A similar threat by China has to be considered in the long run.

In any case, there is a distinct possibility that Beijing would face significant counter-balancing among maritime powers in the Indian Ocean.

(2) Nearer-Term Risks?

In the meantime, there is a growing pressure in the eastern gateway of the Indian Ocean. Beijing has upped the ante in the South China Sea (particularly Vietnam and the Philippines) diplomatically and militarily. In the absence of the United States, China would be on track to become the dominant maritime power in that sub-region.

However, the more immediate challenge is actually from Iran but in the Strait of Hormuz. The United States will need to keep two things in place, first, defense-in-depth and deterrence to respond from the Indian Ocean region to any Iranian activities against the Strait of Hormuz an immediate strategy, and second, dissuasion vis-a`-vis Chinese pressures from the South China Sea on chokepoints at that end of the Indian Ocean as a longer-term strategy.

2. Components of a U.S. Indian Ocean Strategy

The three U.S. geostrategic interests at stake, i.e. “maintaining a secure highway”, “sanitizing great power rivalry in Asia”, and “defending chokepoints” are going to be on top priority for the U.S. In this context, listed below are the five interlocking principles for the U.S. National Security Council.

(1) Resources Matter

The Obama administration sent a signal by promising not to take defense cuts out of the Pacific Command. However, even the current plans would decrease U.S. defense spending by the size of Japan’s defense budget each year. This is of considerable significance as Japan is the largest U.S. ally in the region and the sixth largest defense spender in the world. The Pacific Command’s ability to execute its mission could seriously degrade. Japan or other homeports in Australia and Singapore could be based to engage exercises and demonstrate presence in the vast region, but deep budget cuts would affect how much the Pacific Command could actually engage and demonstrate its presence in the vast region. It is a fact that a crisis with Iran in the Strait of Hormuz will draw capabilities out from the Pacific Command’s area of responsibility (AOR) because there will be less capability based in Europe.

(2) Diego Garcia and Australia Matter

Although the United States does not need a major new military presence in the Indian Ocean except for Diego Garcia, HMAS Stirling, a major Australian Naval base in Western Australia, and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands. HMAS Stirling offers deep-water port facilities which are capable of expansion to accommodate aircraft carriers, support facilities for surface vessels and submarines, and ready access to extensive naval exercising areas. In World War II, up to 30 U.S. submarines were based in the same area. A relatively modest investment in upgrading the existing Cocos Islands runway and facilities which are located in Australian territory 3,000 kilometers northwest of Perth, roughly midway between the Australian mainland and Sri Lanka would provide a valuable staging point for long-range U.S. aircraft operating into the Bay of Bengal and beyond.

(3) Balance of Power Matters

The United States does not need to plan for significant increases in its permanent military presence in the Indian Ocean except for Diego Garcia, HMAS Stirling and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands. U.S. strategy should focus on supporting Indian preeminence in the Indian Ocean and closer U.S.—India strategic cooperation, recognizing that there are realistic limits to this that stop well short of a full-fledged alliance. In addition, U.S. strategy should encourage closer alignment among the maritime democracies. Enhanced strategic consultations would be useful in time for return to the U.S.—Japan—Australia—India ‘‘Quad’’ concept. A strategy of gradual alignment among maritime powers in the Indian Ocean has three advantages: first, it helps to dissuade China from seeking parity over India alone, thus securing the highway; second, it provides an arena outside of Beijing’s most sensitive areas of ‘‘core interest’’ to demonstrate that Chinese assertiveness will make counter-alignment strategies by other states in the region; and third, it creates capacity and norms for security cooperation that will discourage unilateral power plays in response to piracy, terrorism, or other littoral challenges in the Indian Ocean by China.

(4) Regional Architecture Matters Less…In This Case

It remains doubtable whether there is another architectural solution to the problem comparable to the U.S. approach to ASEAN or the Western Pacific. The U.S. government should be careful about broad U.S.-led Indian Ocean initiatives for four reasons as listed below. Firstly, if the most important U.S. strategic interest in the region is supporting Indian leadership then it should not undermine or challenge that leadership. Secondly, the areas where U.S. and Indian definitions of national interest often diverge such as the issues of seabed exploitation or climate change, suggesting that these should be handled quietly in bilateral or global forums rather than as centerpieces of an Indian Ocean regional initiative. Thirdly, India’s residual non-alignment pathologies tend to come out often in multilateral forums. India’s strategic culture is changing in the direction that will underpin U.S. strategic interests. Thus, U.S. strategy should reinforce the changing bilateral cooperation or mini-lateral efforts such as the Quad or the new U.S.—Japan—India trilateral dialogue. Fourthly, because the challenges facing the Indian Ocean region are simply too diverse, one-size-fits-all architectural solution is needed.

(5) Taiwan Matters

If U.S. policy shifts toward active promotion of Taiwan’s independence from the mainland it would invite direct Chinese confrontation and produce little positive results in the Western Pacific and the Indian Ocean. However, strong and sustained U.S. commitment to the Taiwan Relations Act and opposing unilateral changes to the status quo in the Taiwan Strait is critical. Chinese coercion of Taiwan through economic or military means would weaken U.S. and Japanese strategic influence in the Western Pacific and encourage the PLAN to focus on the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean eventually. In contrast, if democratic Taiwan, for the sake of security concerns, suggests positive changes in China’s own political and strategic culture, it makes a positive contribution to a broader Asia including the Indian Ocean region.

3. A Strategic Problem: Not a Crisis

“Despite all the recent attention, there is no immediate or looming crisis in the security of the Indian Ocean.” Hence, it is important to preserve these interests by old-fashioned alliance management, maintaining naval power in the Persian Gulf, the South China Sea and the highway (supported from Diego Garcia and Australia), maintaining vibrant alliances in East Asia, clear commitments to Taiwan, and developing a strategic partnership with a rising India.

II. Comments −India is Rising as a Naval Power-

What kind of interests Japan and U.S. have in the Indian Ocean? How vital are these interests? It is to these important questions that I now turn. Military operations in the Indian Ocean have been not been discussed exhaustively either by Japan or U.S. However, both have implemented certain military operations in the region. Many examples may be cited from the past. For example, in World War I, Japan escorted the Allies ships in the Indian Ocean. In the Battle of Ceylon in 1942, it sent five aircraft carriers for the battle. Further, in World War II, Japan’s submarines attacked sea lines of communication in the Indian Ocean region. Similar examples may also be cited from the post war era. As a peaceful country, Japan participated in the mission of minesweepers after the Gulf War in 1991. Since then, cases of Japan’s involvement in the region have only grown with time. Several examples will substantiate this claim. The refueling mission after 9/11 from 2001 to 2009, the disaster relief operation for the large earthquake offshore Sumatra in Indonesia and the tsunami in the Indian Ocean in 2004, the disaster relief Operation in Pakistan in 2007, the measures against piracy in the Indian Ocean Region since 2009 etc. However, there remains a gap. Despite Japan implementing these military operations in the Indian Ocean for a long time now, there are few sufficient systematic researches and discussions that explore the various dimensions of the connections between the security of Japan and the security of the Indian Ocean.

Compared to Japan, United States has implemented bigger and more aggressive military activities in the Indian Ocean. Again, we could illustrate with examples from the past. In the Sino-Indian war in 1962, US dispatched aircraft carrier to support India. In the Indo-Pak war of 1971, after the British decided to withdraw from bases “East of Suez”, US dispatched an aircraft carrier to support Pakistan in constructing base in Diego Garcia. Naval ship visited for refueling and planned to set up the transmission facilities of Voice of America in Trincomalee in Sri Lanka. These activities compelled India to send Sri Lanka more than 60,000 troopers to Sri Lanka from 1987 to 1990. Further, in 1972, U.S. added the India Ocean region as the area of responsibility of US Pacific Command. After the 1973 Arab Israeli War, U.S. became far more concerned with their interests in the Indian Ocean. The Chief of U.S. Naval Operations explained to the Senate that the Indian Ocean was the key area where the balance of power changed on 20 March 1974.

However, despite such kind of military activities, there are certain other factors that better explain US military activities in the Indian Ocean. For example, in 1970s, the main driving force behind US military activities in the Indian Ocean came as a response to the naval activities of USSR. This was typically the Cold War power politics as USSR was concerned with U.S. submarine based ballistic missiles in the Indian Ocean that had most part of USSR within their reach. It would be insightful to compare that U.S. naval activities in the Indian Ocean was one fourth or fifth of the naval activities of USSR. Some scholars would argue that the reason behind US activities in Trincomalee in Sri Lanka had also come as a response to USSR invasion in Afghanistan. Locating this situation in the context of the Cold War, it can be understood that Pakistan was vital for U.S. as a support base for anti-Soviet guerrilla in Afghanistan and that U.S. wanted to divert India’s attention from Pakistan to Sri Lanka .

These historical examples indicate that the most important part of the Indian Ocean as highway of international commerce for Japan and US is not the Indian Ocean itself, but the sides of the Indian Ocean like the Strait of Holms and the Strait of Malacca. In the present times, China is constructing ports, setting up military facilities, exporting naval weapons and surveying by using disguised fishing boats in the countries around India. Further, there are also reports about China’s nuclear submarine’s activities in the Indian Ocean. If China integrates Taiwan and sets up bases in the countries around India, PLAN will expand the area of assertive activities. Logically enough, under such circumstances, the sense of crises is rising and we want a more detailed analysis about China’s such activities in this article. Although this information indicates that Indian Ocean will be the more important area in near future, a review of the security situation in the Taiwan Strait, East China Sea and South China Sea (West Philippines Sea) would assert that the situation there is far more serious than in the Indian Ocean.

Here comes an interesting analysis. It could be asked why the commentators and strategists in Japan and U.S. focus more on the security problem in the Indian Ocean. Secondly, for U.S., how different is the security situation in the Indian Ocean now than that during the Cold War.

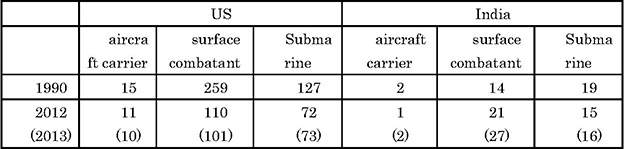

One of the major differences is the comparative scale of the Indian Navy. The government of India has not altered the officially sanctioned force level for the Indian Navy, which comprises of two aircraft carriers, twenty eight destroyers and frigates, twenty submarines since 1964. If we count small ships, the Indian Navy nearly achieved the number in 1990. However, the force level of Indian Navy in 1990 was still not big when compared with the Navy of US and USSR.

In 2012, despite India maintaining the same force level, the comparative scale of the Indian Navy is growing because the number of US Navy has decreased. In addition, having newer and bigger warships as compared to the older ones also indicates that the Indian Navy is improving its capability as a “Blue Water Navy”. Further, the fact that the Indian Navy has trained other navies like submarine forces in Vietnam and Iran and aircraft carrier crews of Thailand Navy is reason enough why the U.S cannot ignore it.

Chart I : The number of warships

*surface combatant: cruiser, destroyer, frigate, corvette (load displacement more than 3000t)

*International Institute for Strategic Studies, “The Military Balance”; Tohru Kizu eds,. “World’s Navies 2012-2013 Ship of the World”, Kaijin-sya.

As a result, there is a genuine possibility that the sense of presence of the Indian Navy has influenced the debate of policy makers and academics in U.S. which, in turn, has influenced the debate in other democratic countries like Japan. The reason why American commentators and strategists focus more on Sino-Indian competition is caused not only because of Sino-Indian competition itself, but also because of the Indian debate which have frankly expressed their sense of rivalry against China. Last but not the least, because the world cannot ignore India as an emerging naval power, Japan and U.S. need to focus on the various dimensions discussed in the preceding sections of the paper. They need to understand the Indian debate on the issue and let India join in the friendly naval powers.

From “Intelligence Analysis (April 2012)”

関連記事